He was the rare artist who inspired not just adulation but imitation

So I turned myself to face me

But I’ve never caught a glimpse

Of how the others perceive the faker

I’m much too fast to take that test

–“Changes,” 1972

Oh, you pretty things! How you loved David Bowie–imagined yourselves in his guise, stood before your bedroom mirrors and preened in mascara, boas and platform shoes. How you turned up the music, then stepped back, striking a chord on your air guitars before singing along, in unison: “Ziggy played gui-ta-aa-ar!”

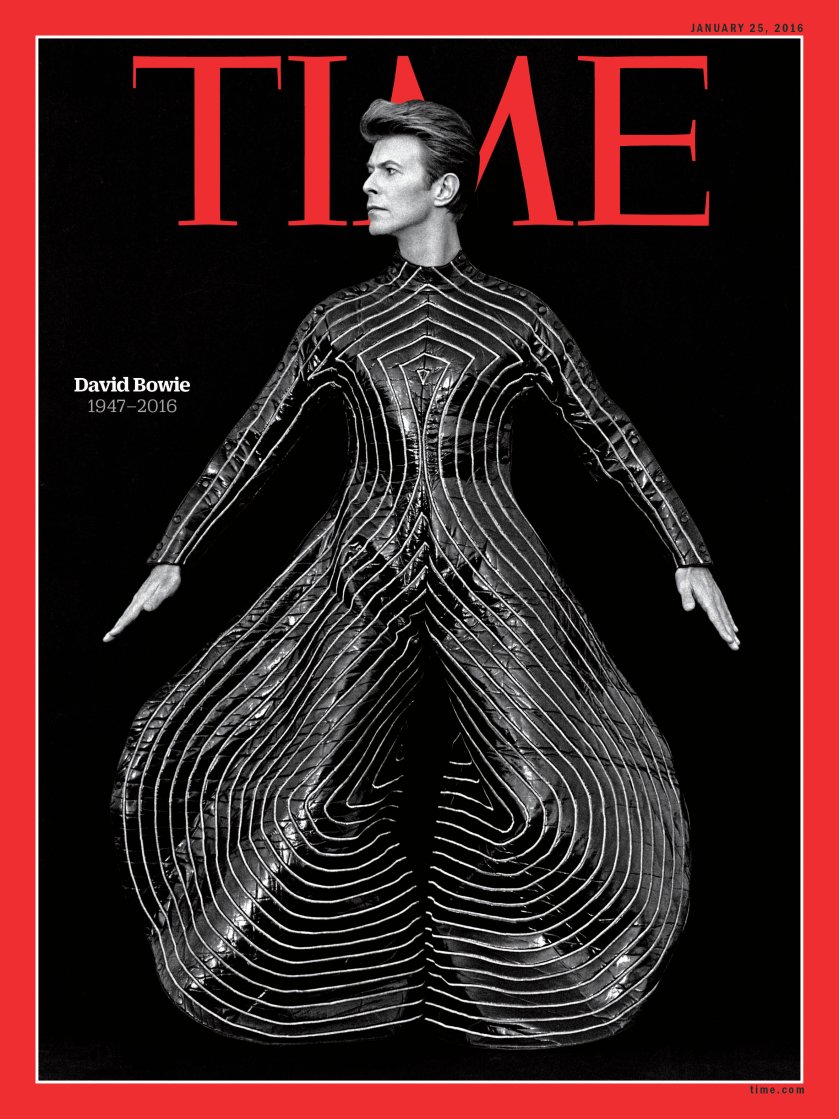

Bowie was the rare artist who inspired not just adulation but imitation, a desire to inhabit and inhale the glittering spectacle he presented on album covers, in music videos and onstage. His five-decade career was an ongoing act of transformation, a series of outrageous experiments in personae and power chords. From Major Tom’s lonely “Space Oddity” rocket ride in 1969 to the disquieting “Lazarus,” his last single and video, Bowie was always seeking his next great role. In illness and death–which came from liver cancer on Jan. 10, just two days after his 69th birthday and the release of Blackstar, his 25th studio album–he found inspiration for his final lines, which he read as passionately and cunningly as anything in his repertoire. “Look up here, I’m in heaven,” he sang. “I’ve got scars that can’t be seen.”

Long before Madonna became the queen of reinvention, Bowie mastered this subtlest of art forms. A man of avid and sometimes fleeting fixations, he moved from inspiration to inspiration, wringing all he could from each incarnation. While his friend and hero Lou Reed followed a singular inner voice, Bowie synthesized his creative force into a string of characters and catchphrases–“Queen Bitch,” “Rebel Rebel,” Ch-ch-ch-“Changes,” “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide”–that altered the course of pop music, infusing it with highbrow ideas about art, identity and theater, as well as a succession of shimmering jumpsuits that would one day be hung in great museums. If Bowie revealed his true self, it was obliquely; he toyed with our perception of him, reflecting back at us our hunger to stand out, to be something special.

“I always had a repulsive need to be something more than human,” he once said of his creations. “I felt very puny as a human. I thought, ‘F-ck that. I want to be superhuman.’”

It’s impossible to pinpoint the moment when the man born David Robert Jones became David Bowie. One might say it was in 1966, when the leader of the failed R&B group Davy Jones and the Lower Third learned that another Davy Jones had signed on to be the heartthrob of a made-for-TV band called the Monkees. His first wife Angela might tell of the night in 1970 when she persuaded his new band, the Hype, to wear the brightly colored costumes she had made. Or in 1971, when he traveled to New York City and met Andy Warhol, Iggy Pop and Reed. Combine all that with fretful reading of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, a few years studying mime with Lindsay Kemp, a friendship with T.Rex singer and glam-rock pioneer Marc Bolan, and repeated viewings of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange–the recipe for rock’s most audacious creature came together just as Bowie flowered as a songwriter.

Bowie was uniquely equipped to embody Ziggy Stardust: cheekbones like Catherine Deneuve’s, a ballerina’s lithe frame, eyes that appeared to be two different colors thanks to a permanently dilated pupil caused by a punch he absorbed at 15, fighting his best friend over a girl. To these uncanny features he added a shock of spiky, carrot-colored hair, a skintight unitard and high-heeled boots. He was a sexy beast who appealed to both men and women, at once dangerous, groundbreaking and iconic.

With guitarist Mick Ronson and producer Tony Visconti, Bowie married his looks to lyrics and music that became anthems for his characters. Ziggy Stardust spoke for a mysterious Starman and announced that young people everywhere were going through changes and everybody else needed to “turn and face the strange.” Aladdin Sane celebrated the rebellious “hot tramp” who tore her (his?) dress and let her mascara run. The fascistic Thin White Duke, an elegant, coked-out and skeletal apparition, crooned menacingly about “Fame” with John Lennon but sounded eminently earnest when celebrating the gusto of carefree “Young Americans.”

If ever the act outgrew the man it was when Bowie unveiled his shiniest invention: the pop singer who released 1983’s Let’s Dance, an unexpected turn from the avant-garde experiments that comprised his “Berlin trilogy” at the end of the ’70s and Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) in 1980. Under the influence of producer Brian Eno, those albums produced hits such as “Heroes,” “Ashes to Ashes” and “Fashion,” but they appeared alongside daring, dark sounds bristling with the newfound energy of punk and new wave. When the title track to Let’s Dance hit American airwaves in early 1983, it created a sensation, dislodging Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” from the top of the charts. Bowie followed it with the Top 20 smashes “China Girl” and “Modern Love.” The videos for all three became MTV staples in the channel’s nascent years. A sold-out arena tour and the cover of TIME followed, as did hit collaborations with Tina Turner (“Tonight”) and Mick Jagger (“Dancing in the Street”). But as Bowie’s popularity grew, he seemed to lose touch with his muse.

No longer a cult icon, the megastar embarked on a massive tour dubbed Glass Spider in 1987. Filled to bursting with stage props, theatrical vignettes, film clips and dancing girls choreographed by Toni Basil, it was an exponential leap forward from anything he had attempted with Ziggy or the Duke. At least 2 million people reportedly saw him perform that year, but critics weren’t kind, charging that pretension had overshadowed ambition. Exhausted by the end of the tour, Bowie himself wondered if he had overreached.

Bowie, who took his stage name from frontiersman Jim Bowie’s double-edged hunting knife in the 1960 movie The Alamo, was born in 1947 to the former Margaret Mary Burns, a waitress known as Peggy, and Haywood Stenton Jones, who did marketing for a children’s charity and was called John. With his parents and a half brother, Terry Burns, David grew up in the London suburbs of Brixton and Bromley when England was still rationing food and clearing rubble left by German bombs. When David was around 8, his father brought home a trove of rockabilly singles, including “Tutti Frutti” by Little Richard. He was immediately hooked. He taught himself to play ukulele, piano and tea-chest bass, which allowed him to participate in local “skiffle” jams, playing the same British-inflected version of American folk music that inspired Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison to form the Quarrymen in grade school. When an instructor at Bromley Technical High School asked what he wanted to be, David’s answer was unwavering: he wanted to be “the British Elvis.”

In 1964, he joined a band called the King Bees as sax player and soon became lead singer. Redubbed Davie Jones with the King Bees, they recorded a single, “Liza Jane,” and landed a spot on the popular British TV show Ready Steady Go! But David remained restless. It wasn’t until 1971 that an explosion of creativity fueled not only his breakthrough solo albums but also hits for Mott the Hoople (“All the Young Dudes,” which he wrote) and Reed (the album Transformer and its single “Walk on the Wild Side,” which he produced). He also put his imprimatur on the Stooges’ highly influential proto-punk album Raw Power, remixing it for his pal Iggy Pop. Five years later he produced, wrote or co-wrote nearly all the songs on Pop’s first two solo albums, including the now classic “Lust for Life” and “The Passenger.”

The ’70s were an era of artistic triumph for Bowie, but they were a scourge on his personal life. He developed such a powerful addiction to cocaine that by 1975, paranoid and out of control, he considered suicide while living on his own in Los Angeles. His erratic behavior was captured in the BBC documentary Cracked Actor, which aired in the U.K. just weeks after his 28th birthday. “I was so blocked … so stoned,” he later recalled. “When I see that now I cannot believe I survived it. I was so close to really throwing myself away physically, completely.”

While he had always had an open relationship with Angela, their marriage grew strained as they delved into the excesses of stardom. By 1976 they had separated and were waging a protracted custody battle over their 5-year-old son, Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones. Bowie moved to Lausanne, Switzerland, and then to Berlin to wean himself from addiction. By 1980, when he finalized his divorce and finally won custody of Duncan, now a well-known film director, he had kicked the habit.

That year, with new vigor, Bowie addressed his legacy in songs like “Teenage Wildlife,” which took swipes at the new-wave artists who had stolen every page in his style book. In “Ashes to Ashes,” he once again sang of Major Tom, only now the astronaut was “a junkie, strung out in heaven’s high, hitting an all-time low.” The haunting song and its groundbreaking video gave Bowie his first No. 1 hit in England.

After the success of his foray into mainstream pop, Bowie made yet another stylistic about-face. He started a band called Tin Machine with guitarist Reeves Gabrels and brothers Tony and Hunt Sales on bass and drums. They made a hell of a racket on their 1989 debut, wreathing their songs in peals of distortion with a grinding backbeat. American pop radio couldn’t stomach it, but it marked the beginning of Bowie’s last phase as a musician–one who would explore any number of sonic highways without worrying about charts and sales. His position in the pantheon was established, and following his 1992 marriage to supermodel Iman and the birth of their daughter Alexandria “Lexi” Zahra Jones eight years later, he seemed genuinely happy.

Throughout the ’90s and early aughts, Bowie seemed to be taking a victory lap. His work was adapted and performed by artists from Philip Glass to Kurt Cobain. In 1995, Bowie reunited with Eno to record the challenging Outside, then his most critically acclaimed album since Let’s Dance. The following year he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 2002, Heathen found him incorporating elements of electronic music. Once again, Bowie played for young audiences when he embarked on a tour with another admirer, Moby. But at a festival in Germany in 2004, he suffered a heart attack and later had surgery to clear a blocked artery. So began a long period of quiet.

A decade went by before Bowie recorded another album. It appeared to arrive from out of the blue with a bittersweet song and music video called “Where Are We Now?” which referenced his time in Berlin in aching tones. The cover of 2013’s The Next Day was an elegant joke: it took the album art from Heroes and superimposed a large white square over Bowie’s face. The message: I may be looking back, but I am not resting on my laurels.

Fans hoped Bowie might re-emerge to perform the songs live, but it was not to be. His last time on a public stage had come seven years earlier when he sang “Changes” with Alicia Keys at a charity fundraiser. Instead, Bowie granted London’s Victoria and Albert Museum access to his personal archives, from which the show “David Bowie is” was mounted with more than 300 objects–handwritten lyrics, photographs, instruments and costumes. The show has been staged in eight countries, is currently on exhibit in the Netherlands and moves to Japan next year.

At a dinner to celebrate the London opening, Tilda Swinton told of how at age 12 she carried a copy of Aladdin Sane for two years before playing it. “The image of that gingery, boney, pinky, whitey person on the cover with the liquid mercury collarbone was–for one particular young moonage daydreamer–the image of planetary kin, of a close imaginary cousin and companion of choice,” she said, echoing the sentiments of generations of Bowie admirers.

Finally, Blackstar arrived with a startling video for “Lazarus,” with Bowie portrayed as a hospital patient with a blindfold over his face and buttons where his eyes should be. In its final scene, the singer stands before us, his voice quavering, before hiding himself away in a dark cabinet. His spark may be extinguished, but his last gesture invites us to open the door and see this dear Lazarus come back to life.