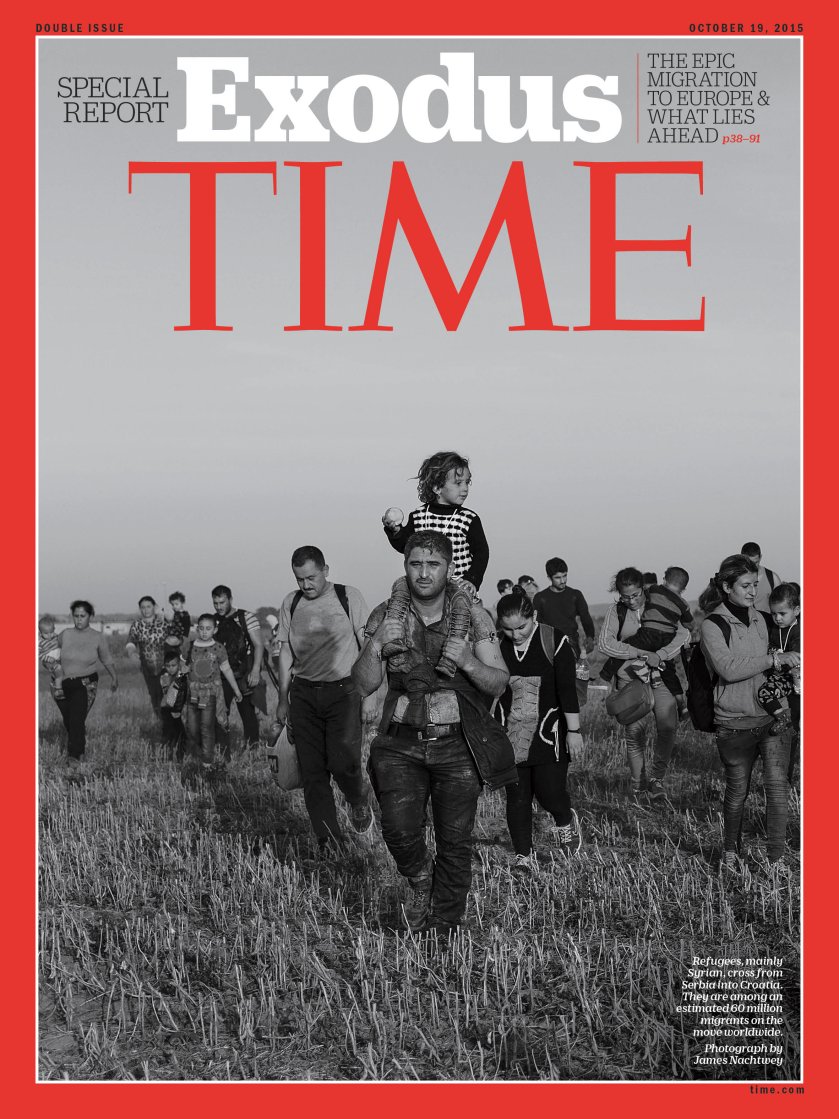

Rarely in modern history have so many been so desperate to flee. Now their brave, and tragic, journeys are reshaping Europe and the world

Americans think of themselves as a mobile people, pulling up stakes for new jobs, moving often.

The U.S. Census Bureau reports that in recent years, roughly every 9th person gets a new address. But Americans tend not to venture far–2 out of 3 moves end in the same county; only 16% cross a state line. And just 3% leave the country, a prospect of dislocation that leaves many mortified and, at some primal level relevant to Europe’s migrant crisis, unsettles even the worldliest. Why else do seasoned travelers ask, “Can someone meet me at the airport?”

Airports are not scary. They are purposely bland, simple to navigate, reassuringly similar. What’s scary is the uncertainty embedded in any journey, a vague foreboding that informed the theory of a flat earth, which merely assumed the horizon was exactly what it appears to be: a precipice. Beyond lay a void like the one at the pit of the stomach when you find yourself in a place where you know no one, darkness is gathering and nothing is like back home.

So when Syrians began emerging from the Aegean Sea this summer, scrambling for footing on the submerged stones that form the doorstep of Europe, the sight produced what 220,000 deaths had not: a surge of fellow feeling. But then few Westerners have actually seen war, and almost no one has witnessed the kind of violence that is emptying Syria, a confounding conflict involving some 7,000 armed groups. The Middle East more than ever seems an excellent place to leave behind, even if it means entering the realm of the migrant.

It’s a crowded realm. More than 600,000 people have entered Europe so far this year, cascading in at a rate–sometimes 10,000 a day–that underprepared, overwhelmed governments quickly declared a crisis. And yet the Syrians–along with the Iraqis and Afghans in the same rubber dinghies–are only the most visible flotsam in a wider and scarcely less insistent stream of human beings, an almost tidal flow that has been running for decades from poorer countries to richer. It leads from Latin America to the U.S., from Burma toward refuge in Malaysia and in most of the rest of the world–Africa, the Middle East, much of Asia–toward the European Union. “It’s not going to stop,” says Behzad Yaghmaian, a professor of political economy at Ramapo College of New Jersey, who wrote Embracing the Infidel: Stories of Muslim Migrants on the Journey West. “Because of globalization, you have awareness of life elsewhere in the world. That’s crucial now. So you move.”

Do you have a signal?

When the travelers climb out of a boat on a Greek island, many raise their arms–first in thanks, and then, a second time, to take a selfie. The images of relief and joy are then uploaded from the smartphone that made the crossing swaddled in plastic bags and rubber bands. “My whole life’s on my phone” is no exaggeration here. In refugee camps, the U.N. distributes local SIM cards for phones and solar generators to charge them. The migrants make their way to new lives by GPS coordinates posted on Facebook or WhatsApp by those who have gone before. Glowing posts on social networks–which border crossing is open, what smuggler can be trusted–are the constellations that guided the travelers to Europe this summer, first in a trickle and soon a torrent. The largest movement of refugees since the end of World War II appeared first in groups of 20 or 30, then in hundreds, trudging down rail beds, emerging from cornfields, and crowding the shoulders of freeways.

If it sounds a little like a zombie movie, the association was not lost on many Europeans, watching from the comfort of their homes. The Periscope application streams video live from wherever someone is holding up a camera phone, and allows viewers to type in comments as they watch. Those comments appear over the live video: action and reaction all on one screen. On Sept. 2, photojournalist Patrick Witty streamed images of inflatable boats coming ashore on Lesbos, and as the exuberant Middle Easterners climbed out, the comments began as gushes:

“God bless”

“Welcome”

“The kids are all okay? OMG.”

Then:

“The invasion of Europe.”

“All Arabs are maggots.”

“Stop the hate talk or I’ll report you.”

Before long the back and forth filled the screen, blocking out the people climbing out of boats. The same will likely happen in person where the migrants finally end up–provided the E.U. decides where that is. Right-wing parties that promote nativism and xenophobia were already on the rise in France, Greece and other E.U. nations well before the latest surge of migrants. Sitting governments in Hungary, the Czech Republic and, more quietly, many of the other 28 E.U. members warn the new arrivals will compete with residents for jobs, government benefits and, ultimately, the identity of Europe. Most migrants are Muslim, so the baggage includes security concerns as well.

“There is definitely a battle of values, with compassion on one side and fear on the other,” says António Guterres, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. But as the E.U. argues where to put the million-plus expected by year’s end, he points out that the 1 million Syrians in Lebanon account for a quarter of that tiny country’s population. The more than 600,000 in Europe so far this year boost the continent’s population by less than 1%. “It’s clear,” he tells TIME, “that Europe has to get its act together.”

How it happened

What do refugees look like? In Africa, they’re easy to spot. Find a war, proceed to the nearest international border, and they’re the people just beyond it, huddled under the standard blue tarps issued by the United Nations. Lacking the means to set off anywhere else, they wait to return home. A map of refugee flows in Africa looks like a chart of central Pacific currents–whorls describing a huge circle.

In Europe, Syrians wade ashore in blue jeans. One’s a pediatrician. Another made music videos. All count as refugees, because they are fleeing war or persecution, the legal definition settled on in 1951 by most of the world amid the postwar debris. The idea was protection, and the good of it could be seen aboard a Greek coast-guard vessel in the early hours of Sept. 7, moments after 40 people were lifted from a rubber boat. Mohamad Balhas, 26, was explaining first why he had been arrested by the Syrian police who tortured him in custody: “Because we don’t love that bastard Bashar.” He was instantly hushed by a friend–a reflexive reaction in a police state. Then a second friend remembered where they were. “No, it’s okay,” he said. “You can say it now.” The three looked at each other for a long moment, then broke out laughing.

In relative terms, it can actually be good to be a refugee. At least it’s better than being a “migrant,” a legal status afforded no special protection under international law, and a label applied to some 240 million people across the globe who have crossed borders, often seeking work. They are Indians building soccer stadiums in Qatar, Eritreans cleaning restaurants in Israel and Senegalese selling knockoff designer handbags on the streets of Rome. They long entered Europe in a steady trickle, at least until the Arab Spring changed things. The mass uprisings of 2011 toppled governments, but when no new order took their place, the combination of miserable populations and vanishing border controls made Libya, for instance, a point of embarkation so frenetic it called to mind Dunkirk.

“My plan was to be a learned man, to have a better future,” says Adeyinka, a Nigerian who spent 19 hours bobbing in a boat with 100 other migrants before being rescued by Italian authorities. Adeyinka’s brother was among the 3,000 migrants killed trying to make the same crossing, a death toll that prompted Europe to crack down on smugglers, and Syrians to search for an alternate route.

They found it close at hand, in Turkey, where some 1.9 million Syrians had already taken refuge. The islands of Greece lie as close as three miles (5 km) off Turkey’s western shores, and Syrians began making the crossing earlier this year, then moved north toward the wealthier E.U. nations in the north central Schengen zone where borders are open. They crossed Macedonia and Serbia, then into Hungary, then into Germany, where on Aug. 25, the Federal Office of Migration and Refugees posted a tweet heard round the world: Syrians who could make it to Germany could apply for asylum there. The news arrived just when refugee life grew dramatically harder back in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. Aid agencies abruptly cut assistance in August, citing “donor fatigue,” leaving 4 million Syrians to feed themselves on $14 a month. At the same time, inside Syria, press gangs sharpened their search for young men to serve in Assad’s army.

The result was a refugee flow that soon resembled a map from World War II: wide arrows swooping from the Middle East into the “soft underbelly” of Europe. And once again, the objective was Berlin.

The search for home

Germany’s role in the crisis is a redemption story. It is, after all, Europe’s dark 20th century history that deepens the anguish in the images emerging from the current migration–desperate civilians facing armed guards across barbed wire, families being separated in the scramble to board trains to a destination they do not know. But this time the journey is one of hope. “I know how the refugee feels,” says Hamidullah Arman, an Afghan who received asylum in Berlin. “But Germany is a lovely country. It’s doing a lot.”

One thing Germany is doing, however, is sorting refugees from mere migrants, a process that the U.N.’s Guterres calls inherently unfair. The reality is that refugees are now generated by more than just war. “There are a number of megatrends overlapping each other and affecting each other,” he says, naming climate change, water scarcity and overpopulation as examples. “And the truth is, these factors are creating more and more situations where life is unsustainable for people in some communities, forcing them to move. They are forced to flee, but they are not covered by the legal status of the ’51 convention. There is a protection gap.”

In human terms, that means perhaps half the people climbing off trains in Leipzig will in a few weeks be quietly placed on flights back to Tirana or Karachi, their applications for asylum quickly closed. And even those likeliest to be offered new lives in Europe face excruciating delays. “There are people like me who come here and are totally lost,” says Muhammad Haj Ali, 26, a Syrian waiting since Nov. 2014 for asylum approval in Germany. “After a while, you stop missing anyone or anything. You’re breathing, the days continue, but that’s it. I don’t have hope anymore. The truth is, when you have hope, you hurt.”

Yet people seem unable to help themselves. In a worldwide poll, Gallup determined that 13% of Earth’s residents would like to move to another country–perhaps 700 million people. The No. 1 destination would be the U.S., which might swell by 150 million if its borders came down.

Compare that with the number of additional refugees–15,000 next year, to bring a sum total of 85,000 for 2016–the Obama Administration has vowed to accept next year, and the limits of compassion, coupled with wariness of Muslims, comes into remorseless focus, even in an immigrant nation. “The U.S. has been really bad,” says Yaghmaian, who himself emigrated from Iran, after years in Turkey, and gathered a lesson in his travels. He remembers visiting Istanbul apartments shared by 40 migrants, all waiting to push westward. But that memory is balanced by the knowledge that his own brother, who has a green card for America, “the greatest country in the world,” chooses to live in Iran, having left once already.

“Home is valuable,” Yaghmaian says. “Home is precious. The smell of home matters a lot.” Leaving it is hard, even for those who know where their journey will end.

–WITH REPORTING BY NAINA BAJEKAL/BERLIN, SIMON SHUSTER/LEROS, VIVIENNE WALT/MESSINA AND PATRICK WITTY/LESBOS