The pontiff offers his vision of faith, duty and moral leadership in his first U.S. visit

You could call America the love child of faith and power. Never happily married, church and state for centuries flexed their muscles, fought their wars, until the Founding Fathers made peace: the Creator endowed inalienable rights; the Constitution would guard them. And America grew rich and mighty, welcoming people of all faiths, favoring none and hosting a 240-year workshop on the role of God in public life.

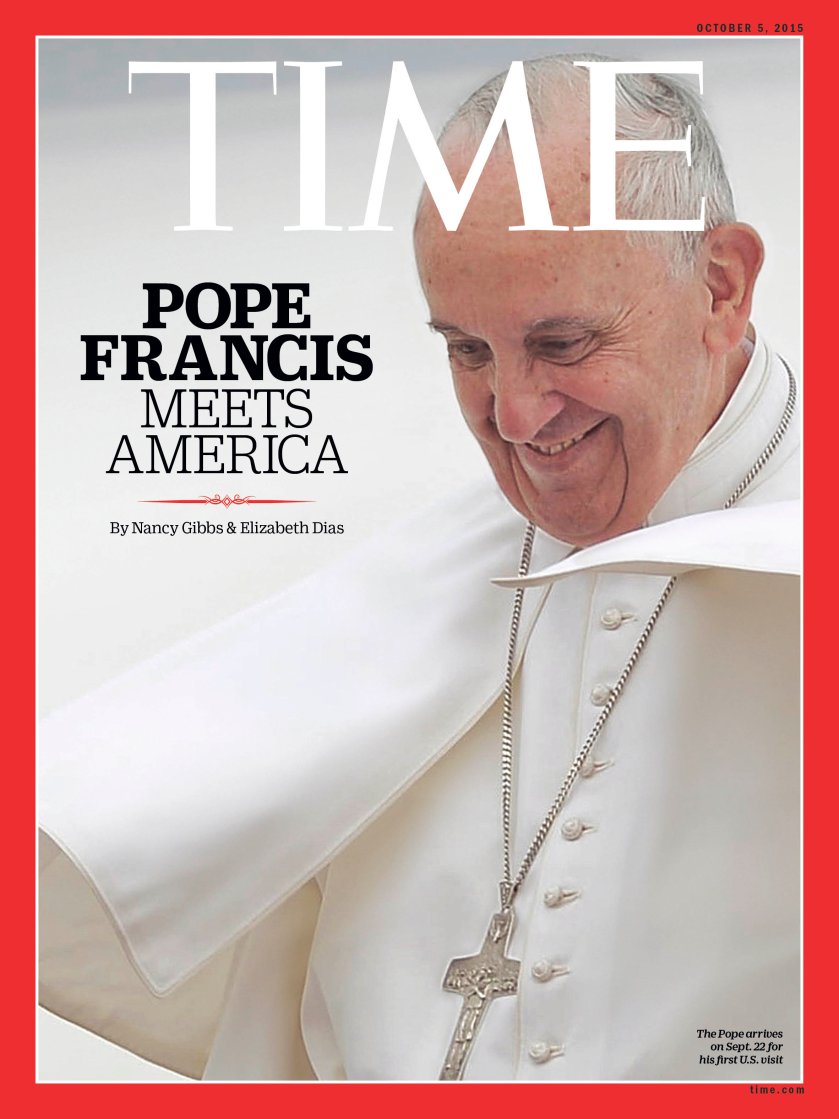

That genealogy felt especially relevant during Pope Francis’ first visit to the U.S. Having called out the world’s superpower more than once for the sins of hubris and materialism, Francis presented himself as pastor more than righteous prophet. He got so busy taking selfies with schoolchildren on his first morning in Washington that he was 15 minutes late to the White House. There, the easy smile that lit his broad features among the children dissolved into a look of distant contemplation–as if to say that the Almighty does not make political endorsements. When the Pope closed his remarks with the words “God bless America,” it was a prayer, not a boast.

He came as a shepherd and was everywhere tending his flock, with the human touch that has enthralled even skeptics with little use for the larger church. He knows the art of an image: he tooled around town in a small black Fiat, dwarfed among the ominous SUVs of the President’s motorcade. But the Pope is not Mother Teresa. He is tough, still sturdy at 78, intensely focused on making the most of his allotted time. He is also a shrewd operator; his early shuffling of the cutthroat ranks of the Curia is proof enough of that. He has kept the old guard of the Vatican guessing and off balance while quietly installing a vanguard of his own.

So it was especially timely that he should have landed on these shores just as America was working through a few of its regular eruptions of confusion and conflict on the borderlands of faith and politics. There is Kim Davis in Kentucky refusing to issue marriage certificates to same-sex couples; here is Ben Carson rejecting the idea of a Muslim President; John Boehner is trying to forestall a government shutdown over funding of Planned Parenthood.

Mahatma Gandhi said those who believe that religion and politics aren’t connected don’t understand either. They’ve forever been connected in this country; in that sense, the Pope was right at home as he balanced his spiritually driven, politically explosive agenda about the poor and climate change alongside the leaders of the country and the world. It was a bracing demonstration of the strengths and limits of moral leadership in the modern age.

We’ve seen elements of this pageant before: Paul VI was the first Pope to visit the U.S., back in 1965, when Vatican II had just begun to open the church to the outside world. He and Lyndon Johnson parleyed in a New York hotel room since at the time the U.S. did not have formal diplomatic relations with the Vatican. John Paul II made seven U.S. visits during his 27-year tenure and, either in the U.S. or Rome, met with every President from Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush.

But none of that occurred in the age of Instagram, when every one of the millions who came out to see him could share the experience with millions more. The papacy becomes ever more personal, the Pope’s message more intimate, a transformation Francis is driving and riding and clinging to for dear life all at the same time. He’s the first Pope to do a Google Hangout and the first to amass over 20 million Twitter followers. The age of authority is giving way to the age of persuasion, which is why his first official declaration was a call to a new era of evangelization. The former nightclub bouncer and slum priest treats every encounter, whether with saint or sinner, as an invitation to mercy. You’re gay? You’re divorced? You had an abortion? Come home. “The heart of the Pope expands to include everyone,” he said in his homily at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington.

Trained in chemistry but skilled at metaphysics, Francis made sure as the trip was being planned that for every action, there would be an equal and opposite reaction. He would come to America to see the world, meet the President, preach to Congress, address the U.N. General Assembly. But he would also visit the homeless at the capital’s Catholic Charities, commune with immigrant schoolchildren in Harlem and minister to inmates at Philadelphia’s largest jail.

Nor was it an accident that the trip began in Cuba, 90 miles and many worlds away from the rich, free, raucous and rowdy mainland where people were happily paying scalpers hundreds to hear his exhortation to lift up the least among us. Seeing America through Francis’ eyes is a mysterious and magical experience for much of the nation, especially for Catholics. The U.S. church is shifting demographically, politically and spiritually, and no one knows that better than a Pope who is hard at work transforming his church in all those same ways. Francis is reorienting the Vatican to the geographic and geostrategic margins, elevating bishops from Cape Verde, Thailand, Haiti and Tonga and including in his early sojourns trips to Asia, the Middle East and Latin America. American Catholicism, meanwhile, is tipping from a dominion of European immigrants and their descendants–Irish, Italian, Polish, French–to one with a pronounced Latin American plurality. But even as it gains new immigrants it is losing adherents: there are roughly 3 million fewer Catholic adults in the U.S. now than there were around the time of Benedict XVI’s visit in 2008.

Evasive of labels and seeking to uphold church dogma without being dogmatic about it, Francis often cites the power of the Holy Spirit when he talks about the importance of service to others. In this way he is especially attuned to America’s current spiritual pulse. With more than six former Catholics in the U.S. for every new convert, according to the Pew Research Center, and a quarter of all married U.S. Catholics wed to a spouse of a different faith, Francis has good reason to say “welcome” in every language. His Argentine roots in the increasingly charismatic Latin American church and his personal inclination to the mystical make him attractive to the nearly 1 in 7 Americans who are religious without a particular affiliation. “He places a great deal of confidence in the presence of the Holy Spirit,” Cardinal Donald Wuerl of Washington says. “The reason he can be so open and so candid is because he has opened himself to the Spirit and feels that Spirit moving within him.”

In his St. Matthew’s remarks, Francis took a moment to pastor to his fellow pastors, reminding the assembled bishops to be gentle shepherds of their diverse flocks and to resist the loneliness that can sometimes come with the job. To leaders of a church still reeling from a decade of scandal, he urged the priests to stay “close to the people,” taking on the world as it is, broken and soiled, not as they might wish it to be. “It is important that the church in the United States also be a humble home, a family fire which attracts men and women through the attractive light and warmth of love… Only a Church which can gather around the family fire remains able to attract others.”

Pope Francis is famous for going off script when that spirit moves him; but he is also a strategic player, laying the groundwork at each step for the next one. In October he will host hundreds of bishops from around the world for the second phase of a Vatican synod to discuss pressures on families, from war to migration to incarceration. In November he will make his first-ever visit to Africa, going to Kenya, Uganda and the Central African Republic. He will not forget the U.S.–a land, as he put it in a message to the American bishops, built by “the epic struggle of the pioneers and the homely wisdom and endurance of the settlers”–but the impressions he gathers here will only put the world’s needs in sharper focus.

Teddy Roosevelt called the presidency a bully pulpit because he grasped the value of using arguments rather than armies to advance an agenda. At a time when so much of American leadership feels flabby and phony, when trust in institutions–Congress, the presidency, the media, the church, police and business–is near all-time lows, a visit by this attractive and enigmatic man reminds us of certain timeless truths. Humility is a powerful muscle; timing is a precious gift; and a genuine desire for progress is more winning, in the long run, than the cunning art of obstruction.