The price we pay for relief

On a chilly evening in late March, Dan McClain was getting ready for dinner when his cell phone rang: Indiana Governor Mike Pence wanted to talk.

Over the previous two months a fast-spreading outbreak of HIV had torn through Scott County, a poor, rural pocket 20 miles from the Kentucky border where McClain has been sheriff since 2011. What began as eight new HIV cases in January had ballooned to 81 by March, quickly becoming the worst HIV outbreak in Indiana’s history. Pence, a Republican and stalwart social conservative, wanted to know how to stop it.

McClain, 52, a squared-away former Navy SEAL whose politics tend to align with the governor’s, had an answer, but it wasn’t the one Pence wanted to hear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had traced the HIV outbreak to Scott County residents who were dissolving and then injecting a powerful prescription pill called Opana that is meant to treat long-term, around-the-clock pain. Their addiction was so severe that abusers were shooting up as often as 20 times a day, repeatedly sharing the same dirty needles. The CDC even found a family that regularly passed one syringe among three generations.

“We need a needle exchange to get clean needles to these people so they’re not spreading anymore,” McClain told Pence. The governor has consistently opposed needle exchanges, but in this case Pence made an exception. Two days after his call with McClain, Pence issued an emergency order overruling a state law and allowing a syringe-swapping program in the region.

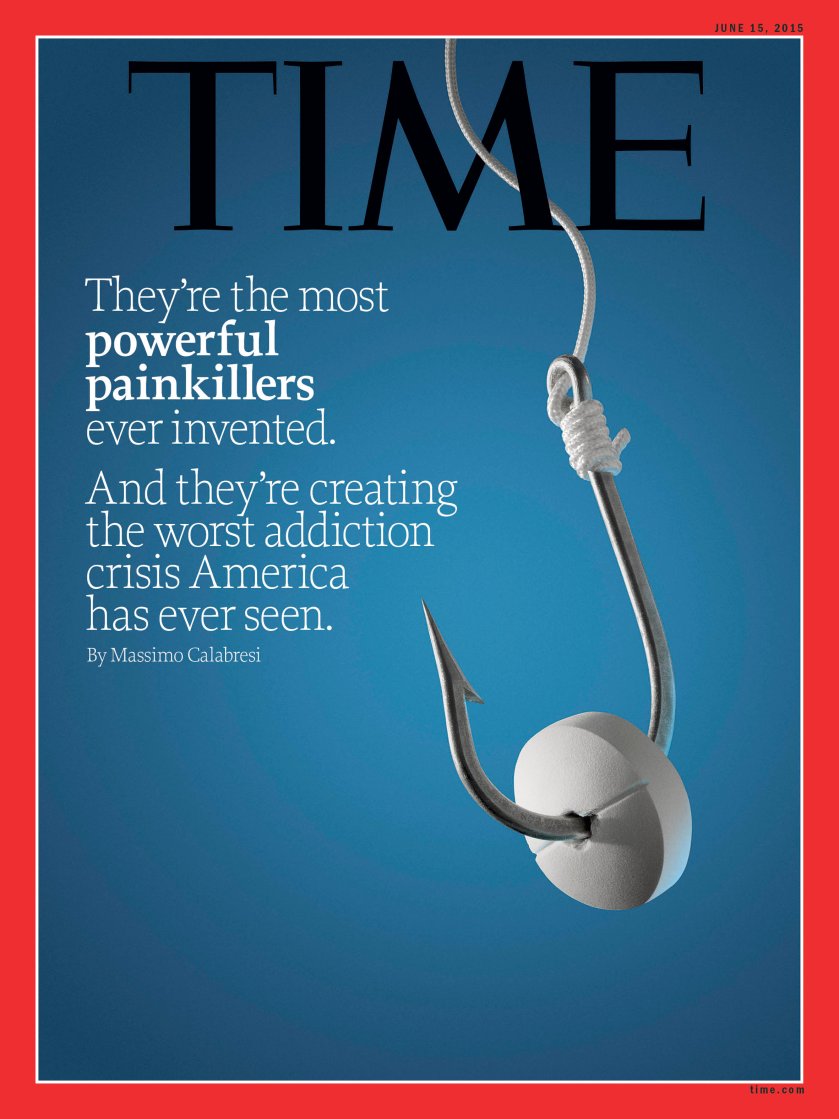

This is not a story about dark alleys and drug dealers. It starts in doctors’ offices with everyday people seeking relief from pain and suffering. Around the nation, doctors so frequently prescribe the drugs known as opioids for chronic pain from conditions like arthritis, migraines and lower-back injuries that there are enough pills prescribed every year to keep every American adult medicated around the clock for a month. The longer patients stay on the drugs, which are chemically related to heroin and trigger a similar biological response, including euphoria, the higher the chances users will become addicted. When doctors, regulators and law-enforcement officials try to curb access, addicted patients buy the pills on the black market, where they are plentiful. And when those supplies run short, people who would never have dreamed of shooting up, like suburban moms and middle-class professionals, seek respite from the pain of withdrawal with the more potent method of dissolving and injecting the pills’ contents, or going straight to heroin.

The result is a national epidemic. The CDC has linked outbreaks of the potentially deadly hepatitis C virus in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia to prescription-painkiller injections. The agency has warned every health care provider in the country to be on the lookout for a rise in HIV. Of the 9.4 million Americans who take opioids for long-term pain, 2.1 million are estimated by the National Institutes of Health to be hooked and are in danger of turning to the black market. Now 4 of 5 heroin addicts say they came to the drug from prescription painkillers. An average of 46 Americans die every day from prescription-opioid overdoses, and heroin deaths have more than doubled, to 8,000 a year, since 2010. For middle-aged Americans, who are most at risk, a prescription-opioid overdose is a more likely cause of death than an auto accident or a violent crime.

It took a tragic combination of good intentions, criminal deception and feckless oversight to turn America’s desire to relieve its pain into such widespread suffering. Most everyone has played a role. Weak research opened the door to overuse of opioids. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ever more powerful drugs for long-term use based only on evidence of their short-term safety and efficacy. Two pharmaceutical companies pleaded guilty to criminal charges that they misleadingly marketed the drugs as safe. Too many doctors embraced the easy solution of treating pain by writing a prescription.

All now agree that the opioid epidemic is a terrible problem, but few are taking responsibility. It has fallen to local law enforcement and health professionals to clean up the mess as addiction and abuse ravage their communities. It’s not easy. The same medical associations that once pressured doctors to hand out opioids liberally now issue conflicting advice over how to combat the problem they helped create. Government scientists admit they have no idea when and whether it’s safe to use opioids to treat long-term pain. Meanwhile, the 2016 presidential candidates are feeling genuine grassroots pressure on the issue. Hillary Clinton is increasingly talking about the “quiet epidemic” after hearing from people in the early-voting states of New Hampshire, Iowa and South Carolina. Kentucky Senator Rand Paul co-sponsored a bill to make medically assisted addiction treatment more widely available. And Carly Fiorina, whose daughter struggled with painkillers before dying at age 35, has called for “decriminalizing” drug addiction.

In Scott County, however, officials have learned that national attention doesn’t always mean things get better. Two years ago, the FDA noted in a letter to the maker of Opana, Endo Pharmaceuticals, that its new, supposedly “abuse deterrent” version of the drug appeared to be driving addicts to inject it intravenously rather than snort it. Now local law-enforcement, health care and social-welfare officials are scrambling to contain the HIV outbreak that has since overwhelmed the county. Brittany Combs, a public-health nurse who runs the new needle-exchange program, says Opana’s grip on those who become dependent is strong. As she hands out bags full of clean needles from the back of her white SUV, she explains that most addicts run through at least 60 syringes per week. “They don’t use it to get high,” she says. “They have to inject that many times a day just to get up and do something, just to function.”

How America Got Hooked

An estimated 100 million Americans suffer from chronic pain, and a quarter of them say it is severe enough to limit their quality of life, according to the Institutes of Medicine. Some get injured at work, others develop arthritis as they age, while others battle chronic diseases like lupus. For much of the 20th century, these patients would receive little more than over-the-counter drugs such as aspirin and acetaminophen for their pain. Codeine and morphine, like their pharmacological cousins heroin and opium, provide powerful short-term relief from broken bones or for recovery from surgery. But because the drugs were viewed as dangerously addictive, legal and professional restrictions meant only those suffering from terminal cancer were likely to have long-term access to opioids.

This began to change in the late 1980s. Researchers started publishing anecdotal surveys suggesting that those rules meant that millions of people might be suffering needlessly. One particularly influential 1986 paper by Dr. Russell Portenoy and Kathleen Foley looked at the experience of 38 patients and concluded, cautiously, that if you were in pain, you might be able to safely take opioids for months or even years without becoming hooked. “Drug abuse is highly prevalent, especially in some cities, in some subpopulations and in some patients with psychiatric diseases,” Portenoy tells Time. For others with no personal or family history of addiction, he says, drug abuse is a “very, very low risk.”

That was a hypothesis some drug companies were ready to test, and soon enough they were applying to the government for permission to do so. Figuring out whether prescription drugs are safe and effective is the job of the FDA, but with the long-term use of opioids, the agency faced a challenge. There were no reliable studies proving opioids worked safely against chronic pain, because it would be unethical to require pain patients in a control group to go months on end without medication. “It’s not practical for us to require people to go for a year on a placebo,” says Janet Woodcock, head of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Instead, Woodcock says, the FDA followed its practice of extrapolating short-term studies to long-term use. When Purdue Pharmaceuticals sought permission from the FDA in 1994 to market a powerful new opioid, OxyContin, to treat moderate to severe pain for extended periods of time, the FDA signed off and went so far as to tell doctors the drug “would result in less abuse potential” since it was absorbed more slowly than other opioid formulations. Over the next 20 years, the FDA would approve more than two dozen new brand-name and generic extended-release opioid products for treating long-term pain, including Endo Pharmaceuticals’ Opana in 2006. “No one anticipated,” says Woodcock, “the clinical community would take to this and start giving it out like water.”

At the same time the new drugs were coming on the market, medical associations and legislatures were telling doctors they should use them. More than 20 states passed laws and regulations designed to expand opioid prescription, including by requiring doctors to inform patients of the drugs’ availability and by making it harder to prosecute physicians who handed them out liberally. In 1998 the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) issued new guidelines for doctors prescribing opioids, saying they could be “essential” for the treatment of chronic pain and neglecting to warn of the risk of overdose. The standard-setting Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations in 1999 required doctors to measure pain as part of their basic assessment of a patient’s health, which had the effect of elevating pain to the same level of importance as objective measurements like temperature and heart rate. Hospitals began displaying posters bearing smiley and frowny faces to help patients indicate levels of pain. (The FSMB says it had to offer doctors its best guidance for using opioids once the FDA approved the drugs.)

In many ways, opioid advocates were pushing on an open door, as many doctors and patients welcomed the loosened environment. With insurance companies limiting the duration of patient visits to increase efficiency, prescribing opioids became an easy option for treating a patient complaining of pain.

Just in case doctors weren’t getting the message, opioid makers went on a marketing blitz. According to government studies and court documents, several companies were particularly active in targeting continuing-medical-education courses, which doctors must take to maintain their licenses. Purdue funded more than 20,000 pain-related educational programs, including some run by the Joint Commission, according to a 2003 Government Accountability Office report. In 2007 opioid makers provided the FSMB $586,620 to help publish a book version of federation guidelines that said opioid pain treatment was essential, according to a suit brought by the city of Chicago in June 2014.

In some cases, regulators, doctors and patients were criminally misled into believing opioids were safe and effective. In 2007 the Department of Justice accused Purdue of deceptively telling doctors OxyContin was safer and less addictive than other drugs. The company and several executives pleaded guilty to misleading doctors and were fined $635 million. In 2008, Cephalon paid $425 million in fines partly for marketing its Actiq opioid, which was shaped like a lollipop, for use against migraines and sickle-cell pain, conditions for which the drug had not been found safe and effective. Actiq withdrew its lollipop, but by then there was no shortage of other opioids available.

By 2011 the number of opioid prescriptions written for pain treatment had tripled to 219 million. By 2014, in some small towns in the southeastern U.S., between one-sixth and one-eighth of the population was taking opioids for more than a month, according to one survey. Such extended use can create resistance to the drug’s effects, leading abusers to increase the amounts they take and putting them at risk of a fatal overdose. By 2011, 17,000 Americans were dying every year from prescription-opioid overdoses.

Opana Comes to Scott County

This rising tide of addiction has touched nearly every corner of the country, including thriving cities like Chicago, New York and San Francisco. But the epidemic is harder to manage in places like Scott County, where poverty, isolation and substandard health care systems leave residents particularly vulnerable. Tiffany Turner found that out the hard way. Other than pot in high school, she says she never used drugs. But after breaking four vertebrae in a 2012 car accident, her doctor gave her opioids. Turner, 28, stayed on the drugs to function at work and soon became hooked, taking them regularly for two years.

By then, with addiction rampant in the county, area doctors were mobilizing to cut patients off. The only pain clinic in Scott County shut down, and several doctors refused to prescribe opioids at all. With her husband ill from renal disease (he died in 2014) and bills mounting, Turner felt she had to self-medicate to keep her job. “I went to the street,” she says. Even amid Scott County’s crackdown, the local black market was flush with opioids. Opana was selling for $25 to $30 a pill, and she started shooting it up.

In 2010, as law enforcement was cracking down on pill mills around the nation, Endo Pharmaceuticals declared the strategic goal of making Opana the No. 2 treatment for moderate to severe long-term pain after OxyContin, according to the court documents filed in the Chicago case. One of the ways the company aimed to increase market share was by assuring doctors it was safe. Endo created a website and funded advertising supplements–which sometimes didn’t identify Endo as the author–that suggested its opioids weren’t addictive, according to the allegations in the Chicago case. “People who take opioids as prescribed usually do not become addicted,” one publication said. Another said, “most health care providers who treat people with pain agree that most people do not develop an addiction problem.” Neither of these statements is untrue.

Endo paid Russell Portenoy, the co-author of the 1986 paper on opioid use for pain patients, to edit a supplement to a peer-reviewed pain journal touting Opana that Endo’s sales team distributed to doctors, according to the Chicago filings. (Portenoy says he doesn’t remember editing that supplement but says he did such work earlier in his career.) The marketing push was felt in southern Indiana. “There was a big drive to use Opana because somehow that would be safer,” recalls Dr. Shane Avery, a primary-care physician in Scott County. Doctors weren’t the only ones making the shift from OxyContin to Opana. At first, the drug killed Scott County’s black-market users outright. In 2011, Scott County saw 21 deaths from Opana overdoses; in 2012 there were 19, McClain and other officials say. Then, as addicts began to adjust their dosage and deaths came down in late 2012, Endo introduced a version of Opana that it said was “abuse deterrent.” In a filing to the FDA in 2012, Endo claimed its new formulation of Opana “would provide a reduction in oral, intranasal or intravenous abuse” thanks to a special coating on the pill.

But the FDA wasn’t buying it. In May 2013, the FDA’s Woodcock sent a letter to Endo warning that there was no evidence to support that conclusion. Worse, the FDA found that the new “abuse deterrent” coating on Opana seemed to make injecting easier than snorting. Woodcock said this raised “the troubling possibility that the reformulation may be shifting a nontrivial amount of Opana ER abuse from snorting to even more dangerous abuse by intravenous or subcutaneous injection.” Yet Endo told its sales staff to repeat its claim that Opana was “designed” to be abuse deterrent anyway, according to documents filed as part of the Chicago case.

The FDA was right. Despite the new coating, the pill was easy to cook down into a liquid that could be injected, according to Scott County officials, and it soon became local addicts’ go-to fix. Combs, the nurse who runs the needle exchange, says even though black-market Opana is more expensive than heroin, abusers strongly prefer the prescription drug. The CDC confirmed as much in an April 24, 2015, report on the Scott County outbreak: 96% of those who tested positive for HIV there this year and were interviewed by the CDC said they were injecting Opana.

Endo denied Opana was at the heart of the outbreak. It suggested generic versions of its drug that didn’t have the “abuse deterrent” coating might be at fault. In April, Endo held a conference call with public-health officials in Scott County. The Endo officials “thought it was a mistake,” says Combs, who was on the call. Around the same time, McClain says an Endo security official called him and offered to help investigate the source of the pills. The Endo official told him the drug being abused couldn’t be Opana because it had been reformulated to be “abuse deterrent.” McClain was skeptical. “I’ve got an evidence room full of Opana over there right now, and I don’t have any generic forms of that pill that are being purchased off the street,” McClain says.

Endo officials declined repeated requests to be interviewed for this article. In response to questions emailed to the company regarding its marketing of Opana and its response to the crisis in Scott County, Keri Mattox, senior vice president for investor relations, said, “Patient safety is a top priority for Endo,” and the company has “an ongoing, active and productive dialogue” with the FDA regarding Opana’s “technology designed to deter abuse.” Mattox says the company supports “a broad range of programs that provide awareness and education around the appropriate use of pain medications” and has reached out to the CDC, Indiana state officials and Scott County health and law enforcement officials, among others.

Portenoy and other advocates for pain patients argue that those who become addicted to opioids do so for reasons well beyond the control of drug companies, including genetic predisposition and a history of addictive behavior. Many of the marketing practices used by Endo are common in the pharmaceutical industry. The U.S. district judge in the Chicago case, in fact, found the city had failed to show that doctors there were misled by Endo; he dismissed that part of the case in May. Chicago, which alleges that Endo and the other drug companies it is suing have hurt citizens and the city by defrauding them, has asked for time to amend its complaint to provide additional evidence to support its claims.

Picking Up the Pieces

Ten years into the opioid epidemic, signs of progress can be found. A new study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found a 19% decline in overall opioid prescriptions and a 20% drop in emergency-room visits for opioid poisoning from 2010 through 2012. But while short-term prescriptions are falling, long-term use remains steady, according to a 2014 study of 36 million insurance claims by Express Scripts, the largest pharmacy-benefit management company in the U.S. And the CDC found opioid overdoses ticked back up slightly in 2013 after falling in 2012. A May 2014 JAMA study found heroin addiction had migrated from “low-income urban areas with large minority populations to more affluent suburban and rural areas with primarily white populations.”

Part of the problem, according to the NIH, is that doctors have no scientific certainty over when and whether it’s safe to use opioids to treat long-term pain. “There is insufficient evidence for every clinical decision that a provider needs to make regarding use of opioids for chronic pain,” a NIH panel on opioids concluded earlier this year. The American Academy of Neurology last year concluded that the risks of long-term opioid treatment for headaches and chronic low-back pain likely outweigh the benefits.

In 2012, the FDA required all opioid makers to adopt a strategy to combat opioid abuse. In September 2013, the agency announced it was finally requiring opioid makers to do several large studies on the risks of powerful, long-term narcotics. The companies are only now submitting their final protocols for those tests–they were supposed to be in last August–and the results on the core questions won’t be known until 2018. Even then, the tests will show only whether opioids are addictive and whether abuse-deterrence properties actually help limit abuse.

Medical associations, too, have tightened their guidance, recommending steps doctors can take to watch for and respond to abuse, but the advice given often conflicts: some require limits on doses and regular tests for abuse while others back testing only for high-risk patients and recommend no caps. Every state except Missouri now has a prescription-monitoring program that makes it harder for abusers to get multiple prescriptions from multiple doctors, but participation by clinicians is often voluntary.

Meanwhile, the backlash against opioids is producing its own backlash. Patients in states with tighter laws say they are unfairly being denied pain relief. Portenoy, the early backer of opioids, now says drug companies “crossed the line” in pushing the drugs but warns that over-regulation “will deprive millions of people, including those who need pain medicine as part of palliative care, access to essential drugs.” In 2013 the Drug Enforcement Administration fined Walgreens $80 million for allowing opioids to get into criminal hands; a year earlier it revoked the pharmaceutical licenses of two Florida CVS stores for lax oversight of opioid distribution. Members of Congress from those companies’ home states are pushing to rein in the DEA’s authority.

The FDA, for its part, continues to behave as if the answer to the opioid epidemic is more opioids. One month after requiring long-term tests of the addictiveness of opioids in 2013, the agency approved an extended-release drug called Zohydro, which is 25% more powerful than Opana and has no abuse-deterrent properties. In allowing the drug, the FDA overruled its own safety advisory board, which had voted 11 to 2 against approval because of addiction concerns. (Zohydro’s maker has since applied for FDA permission to market an abuse-deterrent version.) A year later, in November 2014, the FDA approved Hysingla, which has abuse-deterrent properties but is two times as powerful as Opana. The total annual sales for opioids in the U.S. has grown over 20 years to more than $8 billion. From 2008 to 2012, Opana generated $1.16 billion a year in sales, and in 2012 it accounted for 10% of Endo’s total revenue.

With America awash in opioids for the foreseeable future, health care providers and public officials are searching for ways to help addicts get clean. A drug called suboxone is effective at stabilizing addicts but can itself be addictive, and there are federal limits on how much one doctor can provide. (A bill introduced May 27 by Rand Paul and Democratic Senator Edward Markey would widen the drug’s availability). In southern Indiana, a group called LifeSpring runs a suboxone clinic and claims a 60% success rate in keeping addicts off opioids and heroin. It currently has 16 patients from Scott County and a waiting list that runs from two to nine weeks.

Tiffany Turner says she has tested negative for HIV and is off Opana. She volunteers in Combs’ needle-exchange clinic and tells her story at substance-abuse-education events in Scott County. As of June 2, 166 people in Scott County had tested positive for HIV. The most common path to getting clean there, though, is by going cold turkey in jail. “My jail is the rehab clinic,” says McClain, who has 65 beds and 120 inmates, 90% of whom are in for prescription-drug-related crimes. He’s making room for more. In the dusty lot behind the jail, workers are pouring concrete and setting steel I-beams for an expansion that will add another 135 beds and provide space for treatment and counseling services.