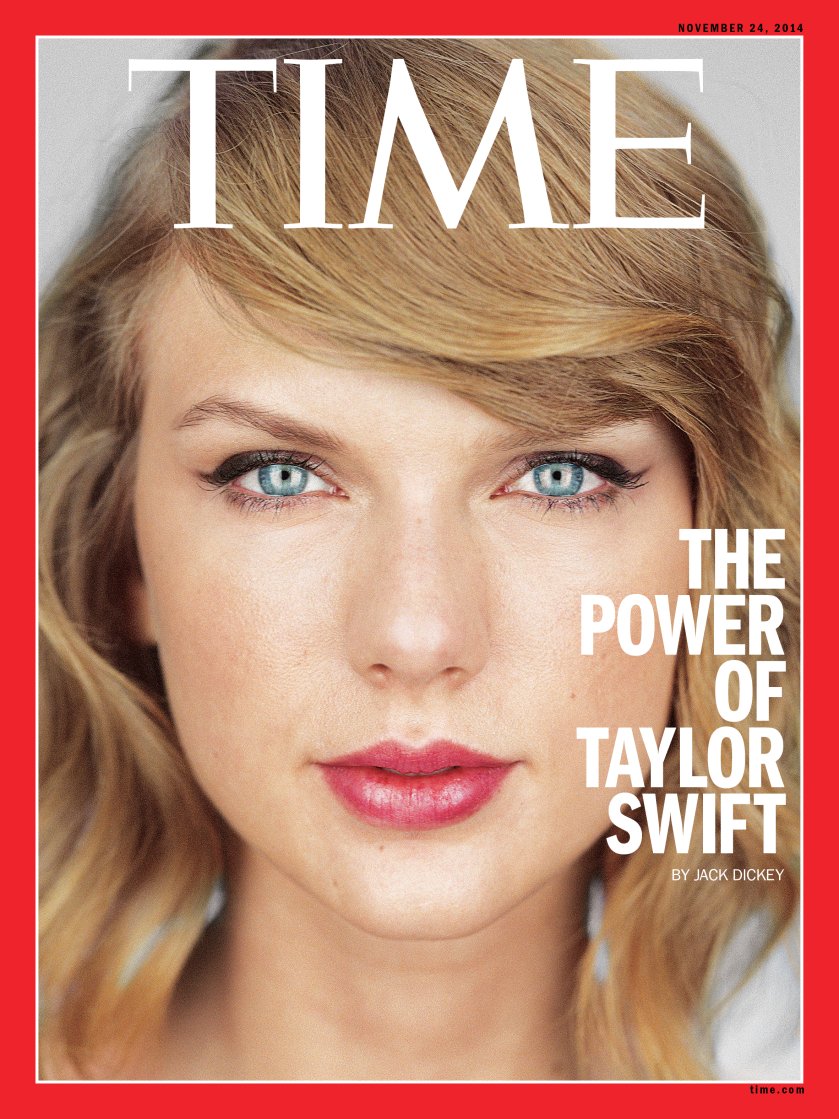

How pop's savviest romantic conquered the music business

Read TIME’s full interview with Taylor Swift.

At eight o’clock on the most exciting night of her life, America’s most important musician was leading several dozen fans in a performance of “Happy Birthday” directed toward a young woman named Caylee, who had just turned 21. She presented Caylee with a bottle of champagne and a card. “Do you know what kind of drinker you are yet?” the 24-year-old superstar asked the 21-year-old, as she put her arm around her. “Are you a happy drunk?”

Earlier that day, in the same Manhattan event space, Taylor Swift had charmed music-biz executives while waiters circulated with frenched lamb and lobster canapés. Her fifth album had come out that morning. She greeted bosses from iHeartMedia–formerly Clear Channel, recently rechristened–and took pictures with them and their awestruck daughters. She hugged Harvey Weinstein, who got her a role in The Giver, like an old friend.

By night, the waiters had switched to pizza, the crowd had turned civilian, and Swift had replaced her sleek all-black ensemble with a navy dress bearing white polka dots and a gold necklace that read t.s. 1989. When she entered, the brigade of fans, prevailingly female and in their late teens and early 20s, queued behind Caylee like supplicants in want of benediction.

Swift is happy to minister to them. “They’re discovering the music that tells them how they are going to live their lives and how they should feel and how it’s acceptable to feel,” Swift says. “I think that that’s kind of exciting.” To her fans she has recently started speaking out on two connected matters of importance to her: the music business and feminism.

On Nov. 3, almost all Swift’s music vanished from Spotify, the online streaming service that claims over 50 million active users, more than 10 million of whom pay for an ad-free and mobile-ready version. Swift’s departure came as a surprise to plenty of those users. She says it shouldn’t have. She believes that Spotify’s particular model devalues her work. “With Beats Music and Rhapsody,” Swift says, naming two competing services, “you have to pay for a premium package in order to access my albums. And that places a perception of value on what I’ve created. On Spotify, they don’t have any settings or any kind of qualifications for who gets what music. I think that people should feel that there is a value to what musicians have created, and that’s that. This shouldn’t be news right now. It should have been news in July, when I went out and stood up and said I’m against it in an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal.” Swift’s decision made such an impact that Spotify’s CEO, Daniel Ek, wrote a blog post defending his business. A Spotify spokesperson told Time that total payout for Swift’s streaming over the past 12 months globally was $2 million. Swift’s label, which receives only a portion of payments, says it collected $496,044 from domestic streams during that period.

The Spotify dustup made one thing especially clear: more than anyone else, Swift knows how to create albums people will pay for. According to Nielsen SoundScan, Swift was the nation’s best-selling artist in 2008 and 2010 and No. 2 in 2012, the last three years she released albums. There’s every reason to expect her to finish No. 1 in 2014. Her first-week figure of 1.287 million copies sold for her new album, 1989, bests any album’s sales week since 2002’s The Eminem Show.

Swift and Eminem have something else in common: the two are the most successful writer-artists to break in and sustain such levels of popularity since the 1990s began. Among her pop peers, Rihanna and Miley Cyrus lean far more heavily on outside songwriters, while Lady Gaga and Beyoncé haven’t matched her sales. Swift is the only artist to have three albums sell a million copies in their first week since 1991, when SoundScan started keeping track. Before 1989, she sold nearly 70 million digital tracks. Billboard named her its woman of the year for 2014, the second time she’s received that distinction in the award’s eight-year history. Her last tour grossed $150 million–the biggest tally country music had ever seen. She has 46 million Twitter followers, putting her in striking distance of Barack Obama, if behind Katy Perry and Justin Bieber, her reported antagonists.

Yet as financially secure as Swift may be, she worries a great deal about her industry’s future and her own, periodically falling into, as she puts it, “rabbit holes of self-doubt and fear.” She says, “It’s a really important thing that I manage my anxiety when it comes to the future, because, you know, I have very few female role models. That scares me sometimes.” She says she looks up to Mariska Hargitay, the Law & Order: SVU actress: “She’s one of the highest-paid actresses–actors in general, women or men–on television, and she’s been playing this very strong female character for, what, 15 years now?” Swift once gave Hargitay and her husband a ride home from an Ingrid Michaelson concert; she later named her cat Olivia Benson, after Hargitay’s SVU character. Swift says she also admires Ina Garten, the Food Network’s Barefoot Contessa, who says of Swift, “She connects with people so well because she’s true to herself. I simply adore her.” Swift even texted Garten a picture of a flag cake she baked on the Fourth of July.

No one in music has captured Swift’s admiration in the same way. It’s not for lack of talent; it’s instead a matter of the challenges female artists face as they age. “I just struggle to find a woman in music who hasn’t been completely picked apart by the media, or scrutinized and criticized for aging, or criticized for fighting aging,” Swift says. “It just seems to be much more difficult to be a woman in music and to grow older. I just really hope that I will choose to do it as gracefully as possible.”

She likes to think, she says, about what her grandchildren will say one day–it’s easier than worrying about her millions of fans. She knows that one way or another, the grandkids will tease her. “But I’d really rather it be ‘Look how awkward your dancing was in the ‘Shake It Off’ video! You look so weird, Grandma!’ than ‘Grandma, is that your nipple?’”

Hiding in Plain Sight

“Shake it off,” 1989’s lead single, had been out for a little more than a month when I visited Swift in September at her parents’ home in suburban Nashville for the first of a series of interviews this fall. The song, sonically Swift’s danciest to date and her second Billboard No. 1, covers the business–significant to her–of bad publicity and “haters” in the world at large.

In person, Swift is taller and thinner than you might expect, and more sharp and sarcastic. She speaks in a low voice, engagingly and crisply, pronouncing every t. We sat at a table on a patio beside a babbling pool, and she tucked her legs under her body while we talked.

Surely every parent with an ambitious child knows by now the origin story of Taylor Alison Swift. Born in, yes, 1989, in Reading, Pa., to Scott, a financial adviser at Merrill Lynch, and Andrea, then a marketing executive for a mutual fund, Swift grew up on a Christmas-tree farm in the nearby town of Wyomissing. As a child she wrote (stories, poems, diary entries) and performed (musical theater, national anthems) whenever she could. She even won a nationwide poetry contest in fourth grade. But country songwriting–Swift has said Faith Hill, Shania Twain and LeAnn Rimes inspired her–scratched the itch better than anything that preceded it. So she flew to Nashville at 11 and handed her demo CD of covers to record labels all along Music Row, but struck out. She tried again at 13 with songs she had written and fared better, earning a development deal with RCA Records. But RCA wanted her to record others’ songs, and she didn’t like that. Besides, the deal had little chance of becoming something real. She opted out and accepted a generous publishing contract with Sony/ATV. She was the youngest songwriter the company had ever signed.

In eighth grade, Swift talked her parents into relocating to Hendersonville, Tenn., outside Nashville, with her younger brother Austin in tow. She would write at her publisher’s office for a few hours each week after school, recounting her day and griping about the flaky boys for whom she had no patience. Her mom would pick her up afterward. While performing at an industry showcase, Swift caught the attention of longtime promotions executive Scott Borchetta. When Borchetta started his own record label soon afterward, in 2005, he snapped up not only Swift but also an investment in his business from her father. The next year, Swift’s first album, Taylor Swift, came out. Three months after its release, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) would certify it as gold, en route to the five-times-platinum certification it would receive by 2011. Easy enough, right?

No. Seemingly everyone who works with Swift cites her uncommon determination and exacting nature. Arturo Buenahora Jr., the former Sony/ATV executive who first signed Swift, says that even at 14 the singer would decline the help of 40-year-old men with long track records of country-hitmaking success. Ryan Tedder, who has written and produced songs for artists from Beyoncé to U2 and wrote two songs with Swift for 1989, noticed her focus too. “Ninety-five times out of 100, if I get a track to where we’re happy with it, the artist will say, ‘That’s amazing.’ It’s very rare to hear, ‘Nope, that’s not right.’ But the artists I’ve worked with who are the most successful are the ones who’ll tell me to my face, ‘No, you’re wrong,’ two or three times in a row. And she did.”

Liz Rose, Swift’s most frequent co-writer, says scores of girls have requested her services in recent years, hoping “to write a Taylor Swift song.” And Rose says she has to tell each one, “Honey, no. Only Taylor Swift could write those songs.”

It isn’t just that Swift pulls nearly all her material from her own life. She writes, at her finest, with a poet’s delicate touch and a dramatist’s nose for conflict. From the first line of her first single, 2006’s “Tim McGraw,” Swift stood apart: “He said the way my blue eyes shined put those Georgia stars to shame that night/I said, ‘That’s a lie.’” In that song, and throughout that album, Swift presented herself as an unlikely mix of coquettish and world-weary, eager and ready to fall in love and equally ready to lose it all. The debut had songs of infatuation and songs of vengeance, all of them mercifully less twangy and anesthetizing than what the rest of mainstream country had to offer.

And off she went, collecting admirers from an older generation with its own songwriting bona fides. Kris Kristofferson, Bruce Springsteen, Dolly Parton–all were wowed by Swift’s craft and poise. At her best she can write stories like Joni Mitchell’s and set them to melodies as memorable as Pharrell’s. But she can also sell like Abba, traverse genres–proving stronger than the format constraints that have strangled scores of high-profile artists–and attract an audience that seems more vast and more loyal than any other artist’s. She has introduced to her fans an earnestness and craft, a form of romanticism, that seems to be in short supply elsewhere in society. She has pulled it off in an era seemingly dead set against such triumphs–one in which audiences are far more likely to splinter than to coalesce–all while masquerading to many as a teen idol, hiding in plain sight.

Carly Simon, who duetted with Swift on “You’re So Vain” in 2013 before a sold-out stadium crowd, says Swift is “a shooting star.” As a songwriter, she reminds Simon of herself–“she’s coy about the subject matter”–but she’s another kind of performer. “I wouldn’t compare her to Joni Mitchell, Carole King or me. Onstage she’s a showman, sort of like Elton John.” Simon has recently purchased Swift’s old tour bus, since she doesn’t care much for flying. She says Swift gave her a discount (“the price you’d charge your sister”) and even left all her linens onboard.

Along for the Ride

One day in early 2014, Tedder, the producer, songwriter and OneRepublic front man, was walking down Abbot Kinney Boulevard in Venice, Calif., when he got a call from Swift. She wanted his help on her new album, and the energetic Tedder knew it was a match from the start. “If anyone else’s bloodstream has trace amounts of Red Bull, hers does,” he says. She told him that she loved the ’80s, and she wanted snapshots of every era of pop from her life. Most important, Tedder says, Swift said she wanted him to ditch every notion he had of her sound. “There is no country on this album. Pretend I’m this new artist who just needs to make this album that defines her career,” she told him.

Even though 1989 is her fifth album, released eight years after her first, it may indeed come to define her career. It marks Swift’s split from Nashville, both literal and figurative. (“For the record, this is my very first documented and official pop album,” she told fans when she announced it.) The old marriage was always one of convenience. The Pennsylvania-reared Swift–no more authentically country than a coastal Cracker Barrel–found in Nashville a chance to make it on the strength of her songs. Had New York City or Los Angeles, the nation’s other two musicmaking capitals, found Swift first, surely they would have sanded down her rough edges, straightened the curls from her hair. Since Swift had been in Nashville, earnestly, from the start of her career, she was welcome to stay as long as she liked.

Her country writing had always been sharp, even by the genre’s tough standards. Fearless offered “Fifteen,” which situates Swift’s ninth-grade romantic troubles alongside those of her real-life best friend Abigail and builds and builds until: “Back then, I swore I was gonna marry him someday, but I realized some bigger dreams of mine/ And Abigail gave everything she had to a boy who changed his mind, and we both cried.” Some of Swift’s detractors said she was crusading for chastity, but the song captures too the wrenching myopia that every high schooler suffers.

Her catalog is filled with songs like that, songs that on second and third listen transcend their narrative focus. Take “Enchanted,” on 2010’s Speak Now, the album Swift wrote without any assistance from co-writers. On first pass, the nearly six-minute-long track sounds like the work of an obsessive, unrelatable mind. But listen again and you hear a song about all of life’s impossible relationships–like the crush that persists for just two stops on the subway–and the dueling senses of opportunity and futility that pervade all affairs of the heart.

While recording 2012’s Red, Swift found herself in need of a new sound. Borchetta, the president of her record label, heard a version of her song “Red” produced by her usual collaborator Nathan Chapman. Borchetta says, “The song was brilliant–great melody. But I told them that the way it was recorded, guys, the production just doesn’t match the song. It needs a pop sound.” So Chapman and Swift asked Borchetta if they could take another crack at it. They did–and it was worse, Borchetta says, than the first pass. “And Taylor basically said, ‘All right, would you call Max?’”

“Max” is 43-year-old Max Martin, perhaps the most successful pop songwriter of the past 20 years. (Swift’s “Shake It Off” marked his 18th No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100; he trails only two guys named McCartney and Lennon.) Martin, who is based in his native Sweden and rarely gives interviews, made his name in the late 1990s writing and producing R&B-inflected bubblegum-pop hits for Britney Spears, Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync. After that era gave way, he found a second life helping Pink and Katy Perry develop their electronic sounds. Martin and his protégé, Johan “Shellback” Schuster, made for unusual collaborators for Swift, given how tight she had kept her pre-Red circle. But she was ready to experiment, and they were ready to help. “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” the bouncy single the three made, became Swift’s first No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. “I Knew You Were Trouble,” a rocking electronic track, would later hit No. 2. She knew she had found her dream collaborators, Swift says, and Martin was her first choice to co-executive-produce 1989 with her.

Her goal with 1989, she says, was a “sonically cohesive” album, one that didn’t straddle genres as Red and Speak Now had. And she has achieved it, writing an album louder, snappier and poppier than anything she released before. Tedder says it was entirely Swift’s doing. “People will look for a hole to punch in the Taylor Swift poster and say, Oh, you’ve got Max Martin, me, Jack [Antonoff] from fun.–established hitmakers. But I think any one of us will tell you, it’s really Taylor. We’re acting as editors. She’s driving, we’re along for the ride.”

On 1989, Swift changes thematically too, deadpanning about her man-eater reputation in “Blank Space” and describing for the first time a girl who cheats on her tomcat boyfriend in “Style.” The old Swift rarely explored gray areas. Yet, she says, “when you’re growing up and essentially publishing your diary for the world to read, you end up incorporating new themes as these themes become evident to you in your own life.”

Her life is full of new themes. Around the time of her previous album release, in 2012, the public seemed to know Swift best as a serial dater–John Mayer and Jake Gyllenhaal were among her famous boyfriends–and a new queen of the kiss-and-tell. (Rolling Stone put her on its cover in 2012 as “The Heartbreak Kid.”) Before that, Swift was best known to nonfans for the time Kanye West filched her mike at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards to say that Beyoncé, not Swift, deserved the award for Best Female Video. (Afterward, West apologized, and even President Obama came to Swift’s defense, calling West a “jackass.”)

But since 2012, Swift’s public image has morphed in tandem with her private life. Her last public relationship ended in January 2013, and thereafter she cut her hair, made a bunch of new friends (Lena Dunham, Karlie Kloss and Lorde) and moved from Nashville, where she had lived and worked since high school, to New York City. “It’s so refreshing to see people move on from the idea that all I do is sit in my lair and write songs about boys for revenge,” she says.

She bought a $19.9 million pair of penthouses in Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood that had once belonged to the director Peter Jackson and soon became, judging by photographs, a fixture on the city’s sidewalks. New York City’s tourism organization announced Swift as its new global welcome ambassador in October, despite her being trapped inside more than she’d like: “If I’m in the mood to be held accountable for every single article of clothing on my body–whether it matches, if it clashes, if it’s on trend–then I go out. If I’m not interested in undergoing that kind of debate and conversation–regarding how I’m walking, whether I look tired, how my makeup is right, what’s that mark on my knee, did I hurt myself?–I just don’t go out.” At least the city’s paparazzi are polite, she says, and yes, she knows how peculiar that rationalization sounds.

The Two Taylors

Swift likes to tell a story about how she came to be named Taylor. Well, she likes to tell two. The first is that she was named for James Taylor, the gentle “Fire and Rain” singer whom her parents adored. And the other: “My mom named me Taylor because she thought that I would probably end up in corporate business–my parents are both finance people–and she didn’t want any kind of executive, boss, manager to see if I was a girl or a boy if they got my résumé.”

The businesswoman wound up in Swift anyway. She has sponsorships with Diet Coke and Keds, and for the sake of album sales she has aligned herself not only against Spotify but with Target. More than a third of Swift’s first-week sales came at the retailer, where among the store-exclusive bonus tracks on 1989 are Swift’s intimate voice memos explaining her craft. Like so many millennials born into the upper middle class, Swift has benefited from the demise of the concept of selling out. By now, Americans are used to brands’ ubiquity, and her product placement is hardly intrusive. What does it matter, really, that “Style” premiered in a Target commercial rather than in a small concert?

Swift says her big sales figures matter “because I realize how important of a statement it makes to everyone to whom statements are very important.” An anxious industry needs some cheering up. What Joni Mitchell once called the starmaker machinery has come to sputter since the Internet’s rise. Many record stores have closed, many music magazines have stopped printing, and MTV has become a reality-TV programmer indistinguishable from any other on cable.

1989 looks backward with its synthesizers, drum machines and Polaroid-centric aesthetic, but Swift also brought back the past with the hoopla surrounding its release. In 1989 the U.S. music industry (top sellers: Madonna, Janet Jackson, Fine Young Cannibals) brought in over $12 billion, adjusted for present-day inflation, according to the RIAA. In 2013? Less than $7 billion. Swift says she wanted to make “an album that’s really an album-album–highlighted, underlined, all-caps, exclamation points at the end of it.” Not too many artists have free rein to do that. But Swift’s fans, enamored and protective of her after years of confessional and moving songs, will support her–and her business prerogatives–whatever her industry’s headwinds.

For instance, she wants to keep playing stadiums. She recalls a rainy night in Foxboro, Mass., in June 2011. The forecast had been for clear skies. “And in the middle of the show, a torrential downpour starts. In my head, the first thing I’m thinking is, Everyone’s going to leave. We’re seven songs into this show, and they’re going to leave. I’m going to be playing to no one. And it’s going to look just like my nightmares look. But instead of leaving, they just danced.”

Her fans’ loyalty extended so far as to police online leaks of 1989 in the days before its release. Album sales mattered to her, and so too would they matter to her fans. Swift later told NPR that it was the first time an album of hers had leaked but not trended on Twitter–and she thanked the Swifties for it.

From them, Swift says, she has enjoyed “extreme, unconditional, wonderful loyalty that I never thought I’d receive in my life, not from a best friend, not from a boyfriend, not from a husband, not from a dog.”

The fans she assembled on the night of Caylee’s 21st birthday were of that loyal breed. Swift herself had picked them from Twitter, Tumblr and Instagram, with vetting help from her staff, to attend the final evening in a series of “1989 Secret Sessions.” All summer, Swift had invited groups of her most fervent followers to her homes (in Manhattan, Los Angeles, Nashville and Watch Hill, R.I.) and to a hotel room in London to preview her forthcoming album. Once they signed nondisclosure agreements, she would bake for them and give them little bits of commentary about the tracks. Then they would pose with Swift for goofy Polaroid shots.

On this final night, though, with the album finally in stores en route to selling nearly 1.3 million copies in its first week, the session had turned a little less secret than the others. Swift played her songs live, two of them for the first time, on a downtown rooftop, simulcasting the performance on Yahoo and iHeart’s stations to an audience worldwide. Behind her, the towers of the Financial District punctured early-evening amber skies. And the lights atop the Empire State Building–a versatile LED rig installed just two years ago–danced to the beat of Swift’s just-released songs. Four years earlier, Swift first sang, “How the kingdom lights shined just for me and you.” On the ground, no one understood what was going on. But up on the roof, Swift’s fans shimmied and shivered, anything to ward off the evening’s chill, as they gazed up at their queen while she looked out over her new, vast kingdom.

PHOTOS: See Taylor Swift Over the Years