As the autonomy of AIs increases, so will their control over the key decisions that influence society.

A broad coalition of AI experts recently released a brief public statement warning of “the risk of extinction from AI.” There are many different ways in which AIs might become serious dangers to humanity, and the exact nature of the risks is still debated, but imagine a CEO who acquires an AI assistant. They begin by giving it simple, low-level assignments, like drafting emails and suggesting purchases. As the AI improves over time, it progressively becomes much better at these things than their employees. So the AI gets “promoted.” Rather than drafting emails, it now has full control of the inbox. Rather than suggesting purchases, it’s eventually allowed to access bank accounts and buy things automatically.

At first, the CEO carefully monitors the work, but as months go by without error, the AI receives less oversight and more autonomy in the name of efficiency. It occurs to the CEO that since the AI is so good at these tasks, it should take on a wider range of more open-ended goals: “Design the next model in a product line,” “plan a new marketing campaign,” or “exploit security flaws in a competitor’s computer systems.” The CEO observes how businesses with more restricted use of AIs are falling behind, and is further incentivized to hand over more power to the AI with less oversight. Companies that resist these trends don’t stand a chance. Eventually, even the CEO’s role is largely nominal. The economy is run by autonomous AI corporations, and humanity realizes too late that we’ve lost control.

Read More: AI Is Not an Arms Race

These same competitive dynamics will apply not just to companies but also to nations. As the autonomy of AIs increases, so will their control over the key decisions that influence society. If this happens, our future will be highly dependent on the nature of these AI agents.

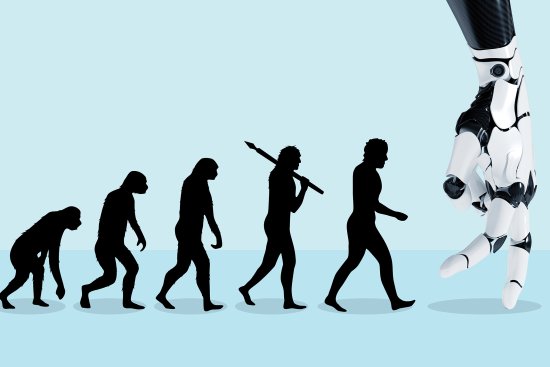

The good news is that we have a say in shaping what they will be like. The bad news is that Darwin’s laws do too. Though we think of natural selection as a biological phenomenon, its principles guide much more, from economies to technologies. The evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin proposed that natural selection will take hold in any environment where three conditions are present: 1) there are differences between individuals, 2) characteristics are passed on to future generations, and 3) the fittest variants propagate more successfully.

Consider the content-recommendation algorithms used by social media platforms and streaming services. When particularly addictive algorithms hook users, they result in higher engagement and screen time. These more effective algorithms are consequently “selected” and further fine-tuned, while algorithms that fail to capture attention are discontinued. This fosters the survival of the most addictive dynamic. Platforms that refuse to use addictive methods are simply outcompeted by platforms that do, leading to a race to the bottom among competitors that has already caused massive harm to society.

In the biological realm, evolution is a slow process. For humans, it takes nine months to create the next generation and around 20 years of schooling and parenting to produce fully functional adults. But scientists have observed meaningful evolutionary changes in species with rapid reproduction rates, like fruit flies, in fewer than 10 generations. Unconstrained by biology, AIs could adapt—and therefore evolve—even faster than fruit flies do.

There are three reasons this should worry us. The first is that selection effects make AIs difficult to control. Whereas AI researchers once spoke of “designing” AIs, they now speak of “steering” them. And even our ability to steer is slipping out of our grasp as we let AIs teach themselves and increasingly act in ways that even their creators do not fully understand. In advanced artificial neural networks, we understand the inputs that go into the system, but the output emerges from a “black box” with a decision-making process largely indecipherable to humans.

Second, evolution tends to produce selfish behavior. Amoral competition among AIs may select for undesirable traits. AIs that successfully gain influence and provide economic value will predominate, replacing AIs that act in a more narrow and constrained manner, even if this comes at the cost of lowering guardrails and safety measures. As an example, most businesses follow laws, but in situations where stealing trade secrets or deceiving regulators is highly lucrative and difficult to detect, a business that engages in such selfish behavior will most likely outperform its more principled competitors.

Selfishness doesn’t require malice or even sentience. When an AI automates a task and leaves a human jobless, this is selfish behavior without any intent. If competitive pressures continue to drive AI development, we shouldn’t be surprised if they act selfishly too.

The third reason is that evolutionary pressure will likely ingrain AIs with behaviors that promote self-preservation. Skeptics of AI risks often ask, “Couldn’t we just turn the AI off?” There are a variety of practical challenges here. The AI could be under the control of a different nation or a bad actor. Or AIs could be integrated into vital infrastructure, like power grids or the internet. When embedded into these critical systems, the cost of disabling them may prove too high for us to accept since we would become dependent on them. AIs could become embedded in our world in ways that we can’t easily reverse. But natural selection poses a more fundamental barrier: we will select against AIs that are easy to turn off, and we will come to depend on AIs that we are less likely to turn off.

These strong economic and strategic pressures to adopt the systems that are most effective mean that humans are incentivized to cede more and more power to AI systems that cannot be reliably controlled, putting us on a pathway toward being supplanted as the earth’s dominant species. There are no easy, surefire solutions to our predicament.

A possible starting point would be to address the remarkable lack of regulation of the AI industry, which currently operates with little oversight, much of the research taking place in the dark. Regulation needs to be done proactively rather than reactively; if something goes wrong in this domain, we may not get the chance to fix it.

The problem, however, is that competition within and between nations pushes against any common-sense safety measures. AI is big -business. In 2015, total corporate investment in AI was $12.7 billion. By 2021, this figure had grown to $93.5 billion. As the race toward powerful AI systems quickens, corporations and governments are increasingly incentivized to reach the finish line first. We need research on AI safety to progress as quickly as research on improving AI capabilities. There aren’t many market incentives for this, so governments should offer robust funding as soon as possible.

The future of humanity is closely intertwined with the progression of AI. It is therefore a disturbing realization that natural selection may have more sway over it than we do. But as of now, we are still in command. It is time to take this threat seriously. Once we hand over control, we won’t get it back.