While the U.S. worries about Chinese hacking, Beijing has built a separate Internet for the 649 million Chinese online

Here’s a day in the life of an average urban Chinese: Wake up, peer at a Xiaomi smartphone for the morning’s WeChat text and voice messages. Spoon breakfast rice porridge with one hand; with the other, use the phone to order a new air purifier on Taobao, just another purchase in the $2 trillion Chinese e-commerce market. Take the edge off the commute to work by streaming an episode of locally popular The Big Bang Theory on Sohu. At work, use Baidu’s search engine and check the inbox on email provider 163.com. Buy a plane ticket on travel site Ctrip. While slurping a bowl of noodles for lunch, peruse the latest musings of actor Yao Chen, who has more than 78 million followers on Weibo. (That’s almost 8 million more than Katy Perry, Twitter’s most popular celebrity.) Choose a restaurant to meet friends for dinner, based on Dianping’s recommendations. Replete with spicy hotpot, order a cab through Didi Dache. On the ride back home, update a dating profile on Momo and zone out with Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils, an online game based on a martial-arts epic.

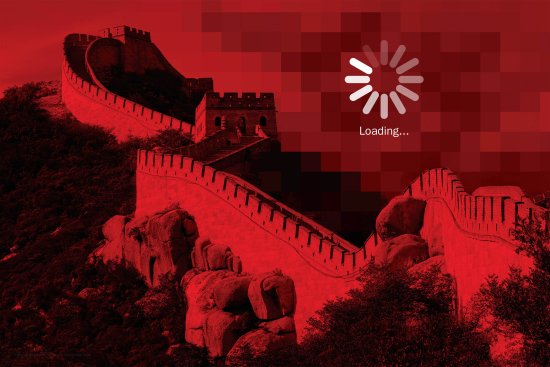

There are 649 million Chinese online, more than twice the number in the U.S. But they live in a parallel universe that is utterly apart from the rest of the digital world. The tech totems of our era—Google, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Wikipedia—are forbidden in China, casualties of the ruling Communist Party’s opposition to free expression. A vast system of online censorship, commonly known as the Great Firewall, blocks the local populace from viewing material deemed dangerous to the state. Since the advent of the Arab Spring, which underscored to Chinese officials the political power of the Internet, mainland censors have stepped up their work, erasing threats to the party—real and imagined.

Cordoned off by the Great Firewall, and largely inhabited by indigenous tech outfits, the Chinese online ecosystem is evolving into the Galápagos of the Internet. But far from a scattering of rocks in the Pacific Ocean, China is crammed with 1.3 billion people who propel the world’s second largest economy. Even as Beijing detaches its citizens from the global Net, the nation’s native tech firms are thriving. Chinese connect to the Internet through homegrown companies, some of which boast market caps greater than those of the foreign counterparts after which they are modeled. Their digital experience matters, both to foreign companies still desperate for a piece of the China market—and contemplating bending their own rules to gain access—and domestic firms profiting from their absence. “We’re basically living in the world of the Chinese Intranet,” says Jeremy Goldkorn, who runs an Internet and media research outfit focused on China. “The question is, How long can this last? Is this the new normal, or is China going to have to eventually integrate with the world?”

China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has made no secret of his ambitions to restore his homeland to greatness. The digital sphere is just one more front in the 61-year-old’s quest to revitalize China and protect it from Western influence. Last year, after vowing to transform the nation into a “cyberpower,” Xi personally took over leadership of a new committee dedicated to the Internet’s management. Since then, China’s digital landscape has shifted rapidly, and Beijing’s influence has repeatedly reached U.S. shores, where Washington blames Beijing for cyberespionage offensives. Chinese netizens who once sounded off on corruption or pollution—always hot topics in China—have been silenced. Some have even been imprisoned. New rules now require Chinese to unmask themselves on social media rather than camouflage controversial thoughts with pseudonyms. “There have been earlier campaigns to control the Internet in China, but they were halfhearted,” says Yang Guobin, a professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of The Power of the Internet in China. “What we’re seeing now is a large-scale offensive that’s comprehensive and well coordinated.”

At least 2 million Chinese toil as online censors, according to state media. Recently, virtual private networks—foreign-operated servers long used to access sites blocked by the Chinese government—have come under open attack. Last year, Gmail was totally blocked for the first time ever. Then Microsoft’s Outlook email service in China was hacked. Communications to and from China, always slightly unreliable, turned erratic. Far from shirking responsibility for such outages, Lu Wei, China’s Internet czar who runs the Cyberspace Affairs Administration, which was formed during Xi’s tenure, defended the changes. “The Internet is like a car,” said Lu, who once served as a top propaganda official in Beijing. “If it has no brakes, it doesn’t matter how fast the car is capable of traveling. Once it gets on the highway, you can imagine what the end result will be.”

The online mocking of wayward government officials that once filled Chinese social media has declined as the party has moved in to control the narrative. Anyone whose posts are shared by more than 500 people can theoretically be sentenced to three years’ jail for “online rumormongering.” The popularity of Twitter-like Weibo microblogs—which served as a clearinghouse for rumor, leaks and breaking news ignored by the state-owned press—has waned, while people have been locked up for comments made in WeChat groups. “Weibo executives told me that they want to stay away from politics,” says Xu Danei, a media commentator who had hundreds of thousands of followers before one of his social-media accounts was shuttered last year. “They want to introduce new apps that focus on daily life, delicious food, things that will make us forget about complaining.”

For many Chinese, though, the Internet behind the Great Firewall works just fine, delivering goods, services and cat videos with a swipe of a smartphone. If a user sticks to Chinese sites, the speed can be plenty fast and the price for Internet access cheaper than in the U.S. China’s information technology and communications market will be worth $465 billion this year, according to market-intelligence firm IDC—40% of total global growth. By 2018, Morgan Stanley estimates, more online transactions will occur in China than in the rest of the world combined. “Just click the mouse and you can purchase almost anything you want to buy,” says Qin Yujia, a car salesman in Shanghai who has sold more than 30,000 cars online in four years.

They may not yet be household names around the world, but in September, e-commerce king Alibaba scored the largest IPO in Wall Street history. The company’s online marketplace, Taobao, serviced by the Alipay payment system, outsells Amazon and eBay combined. Tencent, Alibaba’s rival and designer of games and messaging service WeChat, reached a market cap of $185 billion, more than IBM’s. After its latest round of funding in December, Xiaomi was valued at some $45 billion, making it the world’s most valuable tech startup. The company estimates that it will sell up to 100 million phones this year.

There are few growth markets as promising for tech companies as China’s. The country may have more people online than any other, but half of the population still has yet to reach the Internet. They are surely pining for streaming video and online shopping opportunities. “China is so big, with so many people, that no company can afford to ignore it,” says Liu Xingliang, head of the Beijing research firm Data Center of China Internet. “Personally, I don’t like the Great Firewall. But what can I, or anyone else, do about it?”

China’s market reality poses a quandary for foreign tech firms. Companies whose reputations depend on the free flow of information and privacy rights don’t appreciate restrictions imposed by any government. Yet what publicly traded company is doing right by shareholders if it ignores the largest tech consumer market on earth? Already tech companies have tweaked their offerings to cater to various national laws—and that can have global implications. “Anytime a company invests resources in building the capacity to censor content, then it can be applied in other places,” says Ryan Budish, a fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society. It makes other governments wonder, Budish says, “Oh, well, why couldn’t they do it for us?”

Facebook, which was blocked in China in 2009 after riots in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, hasn’t given up. The company makes do selling ad space to Chinese companies wanting to market themselves abroad. “Our current business focus is to study and learn about China,” says a Facebook spokesman.

Mark Zuckerberg is doing just that, in notably public fashion. In December, Zuckerberg hosted Internet regulator Lu at his office. The founder of a social network that has connected 1.35 billion active users worldwide—roughly the same as China’s entire population—posed for smiling photos with the man who has overseen Beijing’s renewed assault on Internet freedom. Just to make the message extra clear, a copy of President Xi’s collected speeches—hardly scintillating reading—happened to be sitting on Zuckerberg’s desk when Lu visited. During the Lunar New Year festival in February, Zuckerberg posted a video greeting in Mandarin. Will his charm campaign pay off? “If you think of the Chinese government’s litmus test for accepting foreign tech firms, Facebook is pretty socially corrosive,” says Duncan Clark, founder of BDA China, a tech consultancy in Beijing. “I don’t really see how Facebook can square the circle.”

In the infancy of the Internet, optimists imagined that a torrent of free information would flood across national boundaries, perhaps even catalyzing democratic reform in societies under authoritarian rule. China has proved both notions wrong. The Communist Party is firmly in control, just as it was in the earliest days of the web. Despite blocking foreign influences and companies, the Chinese Internet ecosystem is thriving and, as in the case of the mobile marketplace, creating products that rival Western ones. “Do Chinese like being cut off from Facebook?” asks Rogier Creemers, a scholar of Chinese media at the University of Oxford. “Absolutely not. But does that mean they’re seeking liberation from the Chinese state? I have my doubts.”

But Charlie Smith, a co-founder of GreatFire.org, which monitors and circumvents Chinese filters, sees it another way. (His name is a pseudonym used to protect the sensitive work he does.) “Saying that Chinese don’t really care about whether or not they can access information,” Smith says, “is like saying that they are second-class information citizens and they don’t deserve it anyway.” It’s also true that the inconveniences of Xi’s Internet crackdown aren’t limited to dissident types. Google fonts, Twitter embeds and Facebook links are widespread across the Internet, meaning that even if web pages aren’t censored in China, they tend to load much more slowly because of these foreign trimmings. Gmail blockages have affected everyone from factory owners filling overseas orders and students applying to U.S. colleges to scientists trying to access international research.

“It’s much more difficult for me to search for international documents now,” says Cassandra Wang, who studies Chinese IT innovation at Zhejiang University in eastern China. “I do not think it is appropriate to isolate the Chinese Internet from the rest of the world.” A survey by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China found that 86% of 106 polled companies were hurt by China’s new Internet policies. “It is an increasingly onerous cost of doing business here that many companies are finding harder to bear,” chamber president Jörg Wuttke said, noting that 13% of the firms reported that they were nixing or delaying plans to open R&D centers in China.

Even foreign tech companies that have prospered in China, like chipmaker Qualcomm, are having to adjust. In February, Qualcomm was hit with a record $975 million antitrust fine in China, one of a series of huge fines levied against multinationals in recent months. In mid-April, the American Chamber of Commerce in China criticized Beijing’s efforts to force foreign businesses to store data locally—and, more controversially, allow the Chinese government potential access to that online information. The American lobby group dubbed such measures a “big data dam,” akin to the Great Firewall. The European Centre for International Political Economy warns that such data localization could trim 1.1% off China’s GDP.

China’s Internet strategy isn’t just about sheltering the country behind the Great Firewall. U.S. officials have accused Chinese state-backed hackers of stealing American online records. On June 4, it was revealed that hackers accessed the personal data of at least 4 million current and former U.S. government employees—an attack that U.S. investigators said appeared to originate in China. (A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman called the accusations “irresponsible” and said China is also a victim of hacking.) Beyond allegations of cyberespionage, there are other ways in which China appears determined to extend online barricades beyond its national boundaries. In April, a report from the influential Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto described an offensive cyberblast dubbed the Great Cannon, which redirects traffic from Chinese sites like search engine Baidu to foreign websites like GreatFire.org that have helped Chinese circumvent their own government. The Great Cannon is designed to crash those foreign websites by overloading them with traffic.

Even more worrisome, Citizen Lab researchers believe that the Great Cannon could eventually be deployed to spy on or deliver malware to any individual who accesses Chinese web content—even outside China. “Conducting such a widespread attack,” the report concluded, “clearly demonstrates the weaponization of the Chinese Internet to co-opt arbitrary computers across the web and outside of China to achieve China’s policy ends.”

China’s defenders say proposed rules to enhance state authority over the Internet, like an antiterrorism law, are no different from those that allow the U.S. government to spy on its citizens through tech backdoors. (The Great Cannon resembles possible American and British cyberwarfare techniques, as detailed in the Edward Snowden leaks.) U.S. officials are pushing for even more potential access to the encrypted data American tech firms collect. Beijing contends that China is simply strengthening cybersecurity in the post-Snowden era.

But earlier this year, Michael Froman, the U.S. trade representative, hit back, alleging that the new rules “aren’t about security—they are about protectionism and favoring Chinese companies.” The official Chinese perspective is unapologetic. “I can choose who will be a guest in my home,” Internet czar Lu said last year. A February editorial carried by China’s official Xinhua News Agency accused the Americans of hypocrisy: “Uncle Sam itself is the one that poses the gravest and the most ubiquitous threats to other countries, as manifested by the Edward Snowden scandal.”

China’s rulers lead by slogans, and Xi’s catchphrase is the Chinese Dream. This fuzzy vision depends not only on individual Chinese ambitions but also on the resurgence of a civilization that once led the world in innovation: paper, gunpowder and movable type were all invented in imperial China. By 2020, Xi has promised, China will again stand tall as an “innovation society,” with an array of tech firms ready to compete with industry leaders worldwide. In his annual state of the nation speech in March, Premier Li Keqiang unveiled an “Internet Plus” policy that will funnel billions of state dollars into the tech industry. The payoff is clear. One domestic poll found that eight of the top 10 most creative Chinese companies specialized in high tech or the Internet.

Some have already made inroads abroad. Telecom giant Huawei was stymied in its efforts to sell networking equipment in the U.S. after a congressional report labeled the company a national-security threat. But more than 65% of Huawei’s revenue comes from overseas, with the company succeeding not just in the developing world but in Europe as well. The firm, founded by a former People’s Liberation Army officer, is rolling out smartphones and wearable technology in the U.S. Xiaomi aims to flood developing-world countries with affordable alternatives to Samsung and Apple devices. The smartphone maker has begun selling power banks, headphones and fitness bands in U.S. and European online stores. Tencent claims that more than 100 million people outside China, many of whom are ethnic Chinese, use its WeChat messaging service despite concerns that its chats are subject to Chinese filters.

Still, even Wen Ku, the top telecom official at China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, has admitted that many Chinese Internet firms have thrived because of “a good policy environment”—in which they did not have to contend with foreign challengers. It’s telling that while Baidu controls 80% of the domestic search-engine market, two of its engineers say privately that given a choice, they would use Google instead of their employer’s censored service. (Baidu, for example, excludes most references to the June 4, 1989, massacre from search results for Tiananmen Square.) “Competition stimulates innovation,” says Zhejiang University’s Wang. “If you simply block the competitors, this is not the right way for China to be innovative.”

For all of Xi’s ambitions to lead an Internet superpower, the question remains: Will Beijing’s online grip hinder the kind of transformational innovation needed for the nation to further climb the economic ladder? Japan and South Korea both made the transition from churning out cheap knockoffs to epitomizing cool tech. But they did so in far freer societies. “At the end of the day, the party is more interested in control than innovation,” says Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation in Washington, D.C. “They see innovation as a means to get global status and power, not an end in itself.”

There’s no doubt China will continue to spawn exciting tech startups that will make huge profits. By hiring foreign stars—Baidu has recruited American artificial-intelligence visionary Andrew Ng as its chief scientist, and Xiaomi has employed Brazilian Hugo Barra, formerly of Google—and pairing them with a growing population of local researchers, Chinese labs will surely produce results. (Though Ng, it should be noted, is working out of Baidu’s California office.) Authoritarian governance doesn’t forestall all ingenuity. The Soviet Union’s rocketry was world-class, and China’s laser technology is reaching similar heights.

But there’s a difference between individual, technical accomplishments and an environment primed for radical thinking—particularly in an industry that depends on connection. Atkinson often receives Chinese delegations that want to know how to move from Made in China to Created in China. “I tell them, ‘You have to allow for criticism and critical thinking,’” he says. “But then, maybe you won’t have one-party rule. The Chinese leadership doesn’t really see that contradiction.”

Too bad. A want ad for a job as an assistant monitor (as censors are known) for Sina, the portal that runs the biggest Weibo service, sets high standards: a bachelor’s degree, strong English skills, at least one year’s experience in online monitoring and an “enthusiastic and passionate” personality. What if an army of eager college graduates were utilized for more creative pursuits? “Imagine the innovation that could be coming out of China,” says GreatFire.org’s Smith. “That’s what the Internet could do.” For China, and the world.

—With reporting by Gu Yongqiang/Beijing, Victor Luckerson/New York and Sam Frizell/ Washington