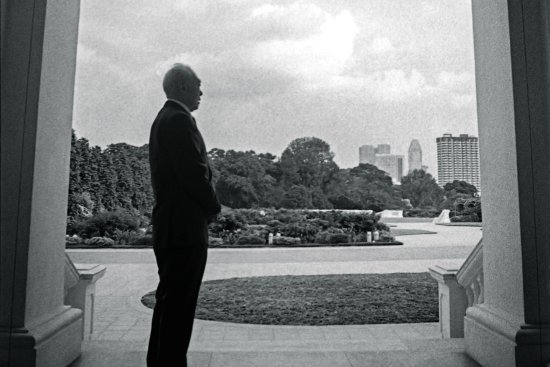

Lee Kuan Yew gave the city-state prosperity, at the cost of freedom

It was the fall of 2005, and Lee Kuan Yew had been engaged in a nearly five-hour interview with Time over two days. The conversation turned to faith as a source of strength in the face of adversity. “I would not score very highly on religious value,” said Lee, then 82, still in good health, and a sort of Minister Emeritus. Yet when he talked about the illnesses and deaths of loved ones, Lee allowed himself a rare moment of vulnerability: his eyes welled up.

Emotional is not a word associated with the hardheaded, severe and supremely disciplined Lee. Neither, seemingly, is mortal—Lee was so enduring a public figure for so long that he appeared to transcend impermanence. But in recent years a mellowing Lee openly broached the subject of dying: he felt himself growing weaker with age, he said, and he wanted to go quickly when the time came.

The time was 3:18 a.m. on March 23, when the 91-year-old Lee, Singapore’s Prime Minister for three decades, died in the 50th year of independence of the city-state that he molded into one of the most sophisticated places on the planet. Lee had been admitted to Singapore General Hospital on Feb. 5 initially for severe pneumonia and, despite brief periods of improvement and the help of a ventilator, his condition deteriorated rapidly following an infection. The nation mourned his passing. “He inspired us, gave us courage, kept us together, and brought us here,” said Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, Lee’s son. “He … made us proud to be Singaporeans.”

Lee’s life traced a long arc of modern East Asian history: the last vestiges of colonialism; the advent of affluence; the introduction of democracy, albeit flawed and limited; the spread of globalization; the decline of Japan and the rise of China; and, now, the retreat to nationalism. He was not so much an architect of change—his stage, Singapore, was, perhaps regrettably for him, too small to be a global actor—as an observer of the way of the world, on anything from nation-building to geopolitics to terrorism, and everything in between. In six decades of public life, Lee preached, berated, pontificated and counseled—not only his own people but also those of other countries, whether the advice was solicited or not.

Overseas, Lee was largely seen as a statesman—“legendary” (Barack Obama), “brilliant” (Rupert Murdoch), “never wrong” (Margaret Thatcher). Upon his death, a chorus of world leaders paid tribute to him.

But, at home, Lee was above all the man in charge. His ethos was both broad and narrow, often controversial, and always trenchant. Government required a long reach. Economic development needed to precede democracy, and, even then, civil liberties should be restricted and dissent monitored and, when he deemed so, curtailed. The community trumped the individual. “Asian values” is what Lee and his ilk called their credo. Though Singapore holds open elections, and Lee’s party had always won big—partly because it delivered, partly because it commanded the most resources—he was not always a fan of democracy. “[Its] exuberance leads to undisciplined and disorderly conditions which are inimical to development,” he said. “The ultimate test of the value of a political system is whether it helps … improve the standard of living for the majority of its people.” Whether Lee intended it or not, his template for Singapore became a model for many authoritarian governments that saw its success as an example of how prosperity could be achieved while controlling freedom.

On the geopolitical stage, Lee was a wily player, especially in maintaining an equidistance between China and the U.S., East Asia’s top two rivals. Both Beijing and Washington trusted him as one who enhanced their understanding of the other.

Even as he invested sovereign funds in China, he provided safe harbor for U.S. warships. In fact, he was an open proponent of a robust U.S. military presence in Asia to help keep the peace. Until the end, he remained a fan of American entrepreneurship and ingenuity.

China, he figured, had some catching up to do, particularly on the soft-power front. His attitude was that its leaders should be engaged but not indulged. “They are communist by doctrine,” he told Time in 2005. “I don’t believe they are the same old communists as they used to be, but the thought processes, the dialectical, secretive way in which they form and frame their policies [still exist].” As early as 1994, Lee seemed to foresee the current maritime tensions in Asian waters when he said, “China’s neighbors are unconvinced by China’s ritual phrases that all countries big and small are equal or that China will never seek hegemony.” But he also argued that China deserved respect: “China wants to be China and accepted as such, not as an honorary member of the West.”

Lee’s arrogance was partly rooted in his strong intellect and his prodigious ability to look beyond the horizon. Today, chiefly because of the foundations he laid, Singapore, tiny and surrounded by hostile neighbors when it was born, has not only survived but flourished—a widely admired banking, tech and educational hub whose GDP per capita is among the highest in the world; a place that constantly innovates and experiments; the Little City That Could.

Historymaker

Lee Kuan Yew was born in singapore on Sept. 16, 1923, to a father he grew distant from and a 16-year-old mother who adored him. The family had lived in the colony for more than half a century by the time of his birth, absorbing the culture of the indigenous Malays and the colonial British. Though Lee’s father himself rose only to be the manager of an oil depot for Shell, the wider clan was established and well-off.

In 1940, when Lee took his final high school exams, he scored first among all students of his age across Singapore and Malaya. By then, war was tearing Europe apart and creeping toward Singapore. On Dec. 8, 1941, Singapore, along with Pearl Harbor, was bombed in a predawn raid. Not one bomb shelter was dug or one city light extinguished, although Singapore’s British colonial governor knew of the Japanese landing in the Malayan peninsula bordering Singapore several hours earlier. Less than three months later, the teenage Lee watched British army soldiers—“an endless stream of bewildered men”—escorted by their Japanese captors to prison camps. Recalling the blunders that led to the island’s defeat in early 1942, he wrote, “In 70 days of surprises, upsets and stupidities, British colonial society was shattered, and with it all the assumptions of the Englishman’s superiority.”

After the war, the British regained rule of Singapore. But Lee, then a law student at Cambridge University, would never forget the debacle of Singapore’s fall. When he returned home in 1950, the 27-year-old law graduate was determined to free Singapore from colonial rule. Displaying a gift for navigating chaos, Lee entered the unruly politics of a country still reeling from World War II while lurching toward an uncertain postcolonial future.

Unemployment and inflation were high. The island’s unions were riddled with communists, many Chinese-educated, inspired by Mao Zedong’s rise to power and eager to stage a similar revolution in Singapore. Offering his legal services for free to unions, Lee built up a grassroots electoral base and became a rival to the communists, who were officially banned. In 1954 he formed the People’s Action Party (PAP) in the basement of his house. Two of the men sitting inside that basement, Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam—the former to be his economic mastermind, the latter his envoy to the outside world—would help Lee through the many crises that would test Singapore in the coming years.

Singapore gained partial independence from the British in 1958, then became part of Malaysia (previously the Federation of Malaya) in 1963. Two years later it was kicked out of Malaysia because of racial tensions—the city-state was mainly ethnic Chinese, the peninsula dominated by Malays—and the antagonism of many senior politicians in Kuala Lumpur toward Lee, whom they considered headstrong and unpredictable. Lee was a month shy of his 42nd birthday, and no longer just Prime Minister of a federated state but of an independent nation with an evaporating economy and not a single trained soldier of its own to defend it.

By late 1965, Lee’s vision for Singapore had formed. It would build its own military, requiring mandatory national service for all male citizens. And instead of trying to piggyback on the commodity-driven trade of its neighbors, Lee would seek investment from outside Southeast Asia, appealing directly to multinationals in the U.S. and Europe. “We had to create a new kind of economy,” he wrote, “try new methods and schemes never tried before anywhere else in the world because there was no other country like Singapore.”

Foreign investment, much of it from U.S. tech companies, did pour into Singapore. In U.S.-dollar terms, Singapore’s gross domestic product grew more than tenfold from 1965 to 1980. It became the world’s busiest port. The dilapidated godowns of the old waterfront were razed to build skyscrapers. Singapore Airlines, the flagship air carrier Lee started in 1972, encapsulated the city-state’s story of success: small, with scant resources and dwarfed by larger rivals, it aimed to be among the world’s best from the outset, and quickly became so.

Lee sweated the small stuff too. Members of the educated elite were encouraged to marry one another so as to improve the gene pool. Citizens were told to flush public toilets. Most kinds of chewing gum were banned to prevent its littering. Spitters were heavily fined, while, for some offenses, the authorities inflicted caning as a punishment. That some of Lee’s social strictures drew mockery or censure abroad mattered little to him. The de facto covenant was this: Singapore’s officials would run the city-state effectively and cleanly—making it an oasis in Southeast Asia—and, in return, its people would toe the line. “If Singapore is a nanny state, then I am proud to have fostered one,” Lee unapologetically wrote in his memoirs.

The Dark Side

despite his successes, lee did not let up. If anything, he tightened his grip on power, curbing free speech and assembly, and went on the attack against political opponents. One of them, the gadfly lawyer and MP J.B. Jeyaretnam, was repeatedly sued for libel by Lee—a legal weapon the government often wields. Jeyaretnam was eventually declared bankrupt and, for a time, barred from contesting elections.

The press also drew Lee’s wrath. In 1971 the Singapore Herald, deemed critical of Lee’s regime, shut down after its printing license was withdrawn by the government. Three years later Parliament enacted a law requiring newspapers that operated a printing press in Singapore to renew their government license annually. Every newspaper company was eventually required to issue “management shares,” carrying greater voting rights than ordinary shares. Owners of these shares had to be Singaporean and were chosen by the government. Then Minister for Culture Jek Yeun Thong defended the measures, saying in Parliament that the local press would remain free as long as “no attempt is made by them, or through their proxies, to glorify undesirable viewpoints and philosophies.” In other words, to act as a free press is supposed to act.

Characteristically, Lee bluntly defended such measures. Speaking to a conference of foreign editors and publishers after the closure of the Herald, he said, “Freedom of the news media must be subordinated to the overriding needs of Singapore, and to the primacy of purpose of an elected government.” Because the foreign press wasn’t subject to local printing laws, newspapers or magazines whose articles were viewed as defamatory either were sued or had their Singapore circulation cut. Among those thus punished: Time, for nine months during the late 1980s. In its latest press-freedom index, Reporters Without Borders ranks Singapore No. 153 out of 180 countries, partly because of the still restrictive regulation of media and a lawsuit against a local blogger.

Eventually, Lee’s combative character began to strike an increasingly discordant note among a growing number of Singaporeans. Sensing the shifting mood, he slowly withdrew from day-to-day governance; in 1990 he stepped down as Prime Minister. But he kept running for Parliament, and his pugnacious manner of campaigning was often grating. Days before the 2011 general elections, for instance, Lee warned the voters of a suburban constituency that they would “live and repent” if the PAP were defeated. Comments like these, later wrote Citigroup economist Kit Wei Zheng, “were widely perceived to have inadvertently contributed to the decline in the PAP’s performance.” That performance was hardly a rout—the PAP retained 60% of the popular vote and 81 out of 87 seats in Parliament—yet, a week after the polls, Lee left the Cabinet. Echoing the belief that Singapore had outgrown Lee’s forceful top-down, paternalistic approach, Lee Hsien Loong, who became Prime Minister in 2004, acknowledged that many voters “wish for the government to adopt a different style.”

Today Singapore is not as tightly wound as before. Its citizens are more vocal, and the government more responsive to their grievances—economic rather than political: the high cost of living, the wide wealth gap and the inflow of migrants. But such burdens of office are no longer for Lee. No-nonsense to the end, he didn’t overthink his legacy. “I am not given to making sense out of life, or coming up with some grand narrative of it,” he wrote in 2013. “I have done what I had wanted to, to the best of my ability. I am satisfied.” So passes the man from Singapore, who became a man of his time.