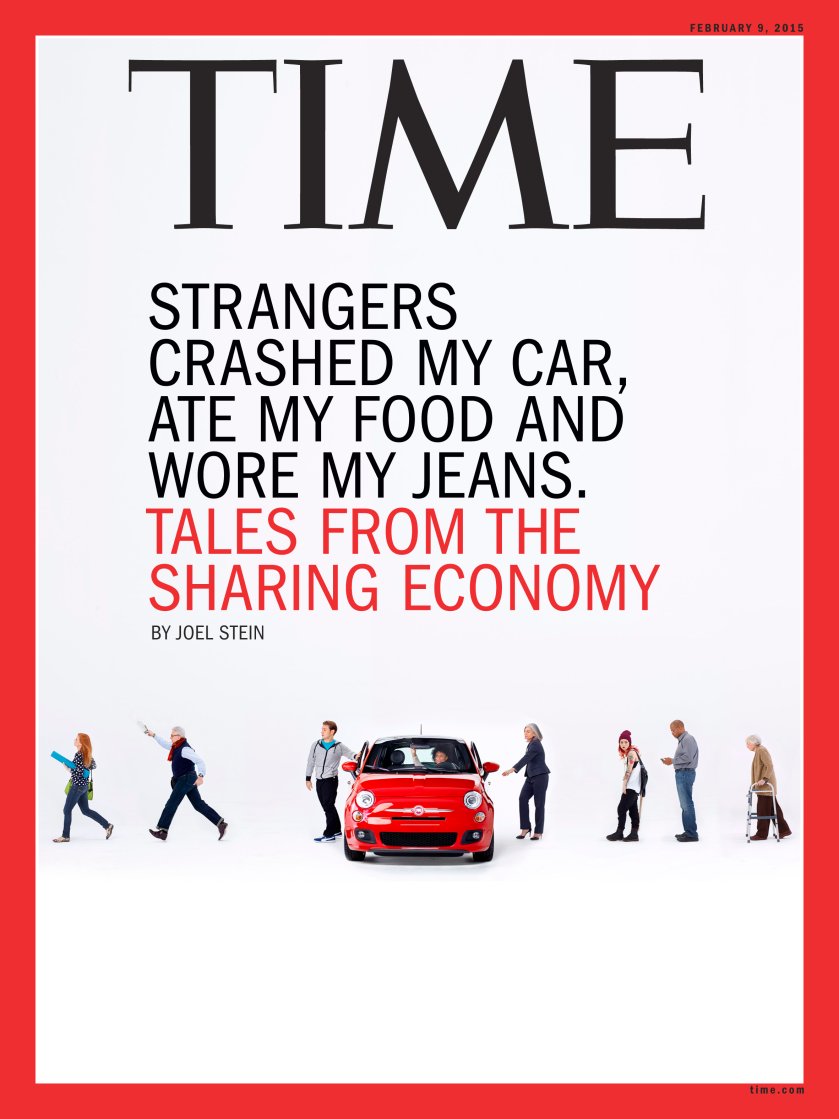

My wild ride through the new on-demand economy

SOME FRENCH GUY HAS MY CAR.

He seemed nice enough–a little sweaty from walking up the hill to my house, but I’ve got faux-leather seats that are easy to wipe clean. I’m renting it to him for $27 a day through RelayRides, a company that facilitated my transition from “dude with a car” to “competitor with Hertz.” The French guy visited me a day early on a practice walk to make sure he could find my place, which is tucked away up a bunch of steep, winding roads. When I saw his sweaty face, I just gave him the keys to my yellow Mini Cooper convertible instead of having him hike back the next day. He returned the car with a full tank and left $27 in cash in an envelope to pay me for the extra day, even though I told him not to. Afterward, the French guy and I rated each other five out of five on the RelayRides app. It was the most successful American-French exchange since the Louisiana Purchase.

A few years ago, the idea of giving some stranger my car seemed as idiotic as my lovely wife Cassandra thought it was when I handed over my keys. In 2008, the concept of building a business out of letting strangers stay in your house was so preposterous, Airbnb was rejected by almost every venture capitalist it pitched itself to, and even the people who wound up investing in it thought it was unlikely to succeed. Now an average of 425,000 people use it every night worldwide, and the company is valued at $13 billion, almost half the value of 96-year-old Hilton Worldwide, which owns actual real estate. Five-year-old Uber, which gets people to operate as cabdrivers using their own vehicles, is valued at $41.2 billion, making it one of the 150 biggest companies in the world–larger than Delta, FedEx or Viacom. There are at least 10,000 companies in the sharing economy, allowing people to run their own limo services, hotels, restaurants, kennels, bridal-dress-lending outfits and yard-equipment-rental services, all while they work as part-time assistants, house cleaners and personal shoppers if they want.

To get here, we needed eBay, PayPal and Amazon, which made it safe to do business on the web. We needed Apple and Google to provide GPS and Internet-enabled phones that make us always reachable and findable. We needed Facebook, which made people more likely to actually be who they say they are. And we needed the Great Recession, with its low-wage, jobless recovery, which made us ask ourselves how many possessions we really need and how much extra we could make on the side. The sharing economy–which isn’t about sharing so much as ruthlessly optimizing everything around us and delivering it at the touch of a button–is the culmination of all our connectivity, our wealth, our stuff.

The key to this shift was the discovery that while we totally distrust strangers, we totally trust people–significantly more than we trust corporations or governments. Many sharing-company founders have one thing in common: they worked at eBay and, in bits and pieces, re-created that company’s trust and safety division. Rather than rely on insurance and background checks, its innovation was getting both the provider and the user to rate each other, usually with one to five stars. That eliminates the few bad actors who made everyone too nervous to deal with strangers. “They figured out a way to move from a no model to a yes model,” says Nick Grossman, a general manager at Union Square Ventures, a venture-capital firm that invests heavily in sharing-economy companies. “The traditional way is you can’t do it unless you get a license. That made sense up until we had data. Now the starting point is yes.”

It’s unclear if most of this is legal. The disrupters are being taken on by governments and the entrenched institutions they are challenging. Uber and Airbnb, exorbitantly funded by Silicon Valley, generate most of the controversy. But there are thousands of companies–in areas such as food, education and finance–that promise to turn nearly every aspect of our lives into contested ground, poking holes in the social contract if need be. After transforming or destroying publishing, television and music, technology has come after the service economy.

In the interest of eliminating bureaucracy, overhead, middlemen and waste, I turned myself into a corporation. Many corporations, actually. Besides a rental-car company, I became a taxi driver, restaurateur and barterer. I would have also become a kennel and a hotel, but Cassandra thought my company shouldn’t grow so quickly that it involved other people’s animals and dirty sheets in our house. It’s a lot of fun being a part of the sharing economy, at least until something goes wrong.

Lyft Me Up

I started by signing up with lyft, Uber’s main competitor, to live out a lifelong fantasy of collecting people’s stories and seeing seedy parts of the city as a taxi driver. After I passed the background check, I went to a training session, where a guy on a yoga ball asked me and 14 other future unprofessional drivers questions like “If you could give a ride to anyone, living or dead, who would it be?” I went with “living” and was tossed a reward of a Dum Dum lollipop. The first guy I went to pick up kept telling me he’d be out in five minutes but never came out of his apartment and, eventually, stopped answering his phone. I called Lyft, and they suggested I change my settings to accept only passengers with 3.5 stars or more. Which fixed everything.

After that, all my passengers were great. I found out what it’s like to be a popular morning-radio DJ in Dubai (not that great), drove a television-network executive to a bar just because he’d heard Gaddafi’s son was there (valid reason) and learned about a new way to get stoned involving a “wax dab” (still haven’t tried it). We all gave each other five stars and never exchanged or even talked about money, since it was all taken care of by our app before anyone got into my car, which made the whole thing even friendlier. I stayed out till 2:30 a.m., fascinated by a woman who’d lost all her money to a con artist she met because of her blackjack addiction, and talked a recent USC grad out of going to law school. In one night, I made $125 (80% of what my riders were charged) and gathered enough material to write a way better song than Harry Chapin ever did.

Soon after, my corporation learned–partly through the sharing economy and partly because it is moving to another house–that it owns a lot of stuff it doesn’t use. But my corporation has a weird attachment to almost all of it, which drives my corporation’s lovely, far more practical wife crazy. Which is why she’s glad my corporation discovered Yerdle.

Three years ago, Adam Werbach, the environmental activist who became president of the Sierra Club at 23, and Andy Ruben, the former head of sustainability at Walmart, started Yerdle to allow people to give away their stuff. Users have given away cars and pianos on the site in exchange for credits they can use to get other users’ unwanted stuff. (I tried offering a pair of fancy jeans as well as Bauer skates I got from the NHL when I played goalie for an Islanders practice session.) More than 25,000 items get shipped through Yerdle every month, and companies such as Levi’s and Patagonia have used it to distribute unsold merchandise to market their brand instead of sending goods to a landfill. “The future we’re excited about is where fewer Patagonia jackets get made and more people have Patagonia jackets,” says Ruben. “We want to make people make things better.”

The economic shift these companies are exploiting isn’t just technological; it’s also cultural. First of all, it’s easier to share now that more people live in cities. (More than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas, according to the U.N.; by 2050 it will be 66%.) “If we were a corporation, it would be our job to get the most value out of things we own,” says Lisa Gansky, author of Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing. “We’re coming to an era where as an individual it’s becoming our job to get value out of it.”

More important, the homes of rich people and millennials are increasingly stark; only poorer people are still piling up stuff in their guest showers and storage units. Material goods have gotten so cheap, they’ve become burdensome. My great-grandmother lugged a brass candlestick on a ship from the old country; I can get a set of new ones on Amazon for $30. “Look at Sex and the City and the Carrie Bradshaw culture of ‘Look how big my closet is and look how much I’ve spent on shoes,’” says Jennifer Hyman, co-founder of Rent the Runway, which lends high-end women’s clothing to its more than 4 million members. “It would be considered kind of yucky today to do that.”

Almost all happiness studies show that experience increases contentment far more than purchases do, and young people intrinsically understand that, fueling an experience economy. Working at Starwood Hotels after college, Hyman learned that the most effective way to earn customers’ loyalty was to get them to have their honeymoon at one of the company’s properties, so she created a wedding registry of experiences such as snorkeling and zip-lining instead of objects like decorative bowls and china sets. A survey conducted last year by the marketing firm Havas Worldwide found that only 20% of people in industrialized countries disagreed with the statement “I could happily live without most of the things I own.” “You can only Instagram your new carpet once,” argues Hyman, “whereas you can take photos of every meal, every vacation, every rented dress.” We’ve moved from conspicuous consumption to conspicuous experience.

So the sharing economy is really the experience economy, and more specifically the experience-it-right-this-second economy. Some companies, like Hyman’s, buy stuff and rent it out, while others, like RelayRides, truly involve peer-to-peer sharing. But they’re all the same to the customer: they get you stuff instantly and easily. “If you think back to what it was like to go on vacation for a week in New York City in 2008 vs. what it’s like seven years later, I would not plan anything now,” says Sam Altman, president of Silicon Valley startup incubator Y Combinator, which was the first investor in Airbnb. “The day I was going, I would first try Airbnb and then try Hotel Tonight. I would never have to launch a web browser or talk to anybody. I would not wait in line for a cab service. I would just be pushing buttons on my phone and sh-t would happen in my life.” Owning things, after all, is a real pain, as Thoreau figured out in Walden when he was horrified by the realization that he had to dust all his possessions. “I would rather sit in the open air, for no dust gathers on the grass,” he wrote. “Man is rich in proportion to the amount of things he can leave alone.”

Phase 2

Six blocks from Yerdle’s two-room, bicycle-stacked office, Lyft takes up a huge three-floor building in San Francisco’s Mission District. Inside, a monitor shows a map that blips whenever a driver is rated five stars, which is 90% of the time. The company has just gotten rid of seven of its offices in other cities, having figured out how to use the sharing economy itself to train drivers: instead of having them come to an office as I did, they now press a button and whatever experienced Lyft driver is nearest picks them up for an in-person lesson. Founders John Zimmer and Logan Green are more hippies than hip. Green wants to fill millions of unused car seats to save the environment and fix traffic; Zimmer’s concern is how isolating and depressing commuting has become.

It’s why Lyft riders sit in the front if they want and genially fist-bump drivers to say hi. “If you think of a 9-to-5 worker, they go into the garage by themselves, they sit in traffic for 30 minutes, they get into their office garage, into an elevator and into a cubicle,” says Zimmer. “What’s the worst form of punishment? What do you do to prisoners when they’re bad? You put them in isolation. One of the most common things we heard is, ‘This restored my faith in humanity.’” Sitting on a tie-dyed couch in a meeting room, Zimmer says his plan is to eventually make every single person a Lyft driver, so people are just constantly picking up whoever is on their way whenever it’s convenient.

The convenience and low price of Lyft and Uber rides are destroying cab monopolies around the world. But it doesn’t hurt that amateur drivers are surprisingly pleasant. No matter how well trained service employees might be, everyone is nicer when they’re dealing with customers directly. Even customers. Nearly everyone who stays at an Airbnb rental, for instance, hangs up their bathroom towels after they use them. You do not want to ask a hotel manager what guests do with their towels. I would still have cable television if I could have bought it from a dude who owned it instead of being transferred by 12 different Time Warner Cable representatives when I tried to alter my service–and then having the company call my cell phone several days later, somehow pre-emptively putting me on hold when I picked up.

This human element has been crucial in fueling the sharing-economy companies. When RelayRides installed a convenient gizmo in renters’ cars that allowed them to unlock it without meeting up to hand over the keys, satisfaction went down nearly 40% and complaints shot up fivefold; when they met in person, rentees kept their cars cleaner and renters returned them on time way more often. Plus, I don’t think Hertz and Avis get the kind of laughs I did when I lent my Mini Cooper, through RelayRides, to an attractive woman in a short dress with a thick Sicilian accent. We talked about the insanity of driving in Rome, and I helpfully explained what the P, D, N and R mean on the automatic shifter.

My corporation is doing so well, I’ve decided to expand and find out if, as I’ve always wondered, I could be a restaurant chef. So, through a Tel Aviv–founded company called EatWith, I’m charging eight strangers $35 each to dine at my house in Los Angeles. I email Grant Achatz, the chef at Alinea, one of the best restaurants in the world, for advice and follow most of it, cooking dishes I’ve made many times and can prepare in advance (onion soup, short ribs, polenta, Brussels-sprout salad and chocolate bread pudding), salting heavily and focusing more on hanging out with the guests than making the food. No one seems disturbed that a 5-year-old boy, my son Laszlo, is the main waiter. One guest, perhaps a little drunk, tells me after I refer to the guests as foodies, “We’re postfoodies. We’re not about the professional experience. We’re about trying new things wherever they come from.” When I tell her this makes me nervous, she insists she loves the short ribs.

I’m pretty proud when my lone reviewer gives me a full five stars for overall satisfaction, five for cleanliness and four for food. I would give myself one star as a restaurateur for overbuying ingredients, underpricing the menu and generally spending more on food and wine than the $30 I get per person after EatWith’s cut. Worse, Naama Shefi, EatWith’s marketing director, who came to the dinner, tells me a few days later that I wouldn’t qualify to work with the company again. “We offer things you can’t find in restaurants. What you cooked wasn’t special or extremely delicious or anything like that,” she says. “In some places you would pass. Maybe in a very small village in Vermont.” She obviously does not realize that corporations have feelings too.

It’s Hard to Share

I’m contemplating my corporation’s next expansion over a beer with a friend when I get a call from the Italian woman who rented my car the day before. She does not know many English words, but accident is one of them. She puts the woman she hit on the phone. I try to explain to her that I am a micro-rental company covered by an online platform called RelayRides. This does not seem to comfort her. My adrenaline is pumping, as if I’d gotten in an accident myself. I have no idea how bad off my car is. But the Italian woman does not seem that concerned, which is making me much more concerned. Why would I rent a car to someone who doesn’t know what P, D, N and R mean? A bit later she texts me: “ok they said this, so I will pay for every think. ok? let me know how much I have to pay and I will do a money transfer.” My romance with the sharing economy has ended.

I’m not the only one. Legislators in cities around the world are not thrilled with how fond the CEOs of many sharing-economy companies seem to be of flouting their laws. Uber, which was so hot it managed to raise $1.2 billion from investors twice last year, is the best known. In December alone, Uber quit its Spanish operations after a judge ruled that some of its services broke the law, giving it unfair advantages over taxi drivers; it appealed decisions in France and the Netherlands prohibiting it from operating its lowest-cost service; it launched in Portland, Ore., in defiance of clear regulations, leading the city’s transportation commissioner to get so mad he said he wished out of spite that he could find a legal way to let Lyft operate there; it saw two California district attorneys file suits claiming that the company doesn’t screen drivers as it says it does; it watched as South Korea indicted CEO Travis Kalanick for willfully breaking the law by operating there; it was ordered out of Thailand; and it got banned in New Delhi after a driver raped a passenger.

In September, Uber hired David Plouffe, the former campaign director and then senior adviser to President Obama, to be its senior vice president of policy and strategy. “Some of these transportation regs are 50 or 60 years old. In the Obama Administration we did a look back at some of these regulations and got rid of some of them. In Germany, you have to return to the garage after every trip,” Plouffe says. Plus, he argues, Uber rides are traceable, increasing overall safety and tax compliance. It’s also true that while the taxi industry argues that well-regulated cab companies are supposedly safer for both riders and drivers, it’s interesting that 30% of Lyft drivers are women, whereas in my experience nearly 0% of cabdrivers are.

In New York City, Airbnb’s largest market, the battle with regulators has been particularly fierce. State senator Liz Krueger says she got involved in the issue nine years ago, when constituents called her office complaining about strangers in their buildings partying loudly and puking in their staircases and about, in some cases, being harassed out of their apartments by landlords who could make more on Airbnb. In 2010 she got a law passed that increased the enforceability of a 1929 regulation prohibiting rentals of less than 30 days. After subpoenaing Airbnb’s data, New York State attorney general Eric Schneiderman issued a report that found that three-quarters of Airbnb’s New York City rentals were illegal. Even though Airbnb shut down about 2,000 rooms in what were essentially unlawful hotels that it said it didn’t know about until it saw the attorney general’s analysis, the law still makes most Airbnb transactions illegal.

“I don’t think government is supposed to be in the job of negotiating with businesses,” says Krueger. “We’re supposed to say, ‘Your business model is in violation of our law, so fix it.’” Katherine Lugar, president and CEO of the American Hotel and Lodging Association, says Airbnb has an economic advantage in not paying the huge taxes hotels do or abiding by the same emergency and security codes or having to accommodate the disabled with costly renovations.

There is, however, something new going on here that pre-existing regulations weren’t prepared for. When does a person become a business? If you’re lending your apartment all the time to friends but not charging for it–no matter how loud or pukey they might be–that’s totally legal. So do you become a hotel the moment you rent your apartment for one night for $1? San Francisco’s board of supervisors decided it’s when you rent it for more than 90 days or don’t live in it yourself for nine months a year. But HomeAway, a site geared more toward longer-term vacation homes, is suing to change that.

Plouffe isn’t wrong: we’ve built up a lot of regulations. In the 1950s, 5% of jobs required a license; now it’s one-third. “One hundred years ago there wasn’t a clear line between someone who ran a hotel and someone who let people stay in their homes. It was much more fluid,” says Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University Stern School of Business who studies the sharing economy. “Then we drew clear lines between people who did something for a living and people who did it casually not for money. Airbnb and Lyft are blurring these lines.”

In an attempt to work things out with regulators, Uber has been on a charm offensive in Europe over the past few weeks, trying to convince local lawmakers that it wants to create 50,000 new jobs in the continent’s moribund economy. When Airbnb started in 2008, its founders attempted to talk to cities about the externalities they might cause, but no one was interested in rethinking laws for a few guys with a few air mattresses and a website. “We were ignored. So we went about pursuing our vision,” says co-founder Nathan Blecharczyk. “There’s very little acknowledgment that over time better ideas come up and policy should be shaped to accommodate these new ideas.” Reid Hoffman, the LinkedIn co-founder who invested in Airbnb five years ago, tells me, “The vast majority of the human race are not good at imagining the upside. They think of risk first. They think, This could be a better life–or death. Ooh, let’s avoid death. But this is so clearly so beneficial, it will be solved everywhere in the world.”

Next Steps

One of the problems that people are worried about, besides death, is that workers in the sharing economy–hardworking, honest people like me–don’t get the benefits most traditional companies provide. “They’re saying, ‘Here’s an app. Use your own labor and your own car and, by the way, we have no risks and no liabilities,’” says Veena Dubal, a postdoctoral student in sociology at Stanford who was studying the history of taxi unions when, thanks to the appearance of Uber and Lyft, her work suddenly became interesting to other people. Worse, she says, they’ve flooded the market with drivers, reducing pay.

The lack of pensions, 401(k)s, health insurance, disability and vacation days is sending workers back to a state not seen since before the New Deal. These new collarless workers–neither blue nor white–have very little tethering them to a safety net. “Technology is making an awful lot of consumers happy and an awful lot of the workers sad,” says Van Jones, who was Obama’s special adviser for green jobs, enterprise and innovation and co-founded #YesWeCode to teach computer science to disadvantaged kids. “There are some parts of the sharing economy that are at best a mixed blessing. It’s a lifeline for people who fell off the boat. It would be better for most people to be on the boat of the old economy.”

But the problems of a workforce that’s about 25% freelancers, with more joining constantly, weren’t created by the sharing economy. Neither were gentrification, the urban housing shortage or the lack of public transportation, all of which Airbnb and Uber have been blamed for.

These companies have also highlighted the inequality gap. When the sharing economy first started, investors assumed rich people wouldn’t bother listing their homes and cars since they didn’t need the income enough to justify the risk and effort. Instead, Airbnb is full of high-end homes and RelayRides has an awful lot of Teslas. The sharing economy is being used heavily by those least in need of it.

When someone invited me to eat at a Chinese restaurant where you often have to wait two hours for a table, she told me not to worry because she pays someone $35 on TaskRabbit, which lets people auction off their services, to stand in line for her. And a few weeks later, I paid various people $5 each on Fiverr.com to make me a jingle, logo, rap song, ad and press release for a Time column. (My editor wouldn’t run the piece I paid someone $5 to write for me.) “Someone said to me that the scaled-up version of the on-demand economy is rich people being driven around and having their stuff delivered by somebody else. That means there’s literally a service class. I think that is happening to some extent,” says Kanyi Maqubela, a partner at the Collaborative Fund, which invests exclusively in sharing-economy companies, including Lyft and TaskRabbit. Jones puts it more bluntly: “When that happens that’s called social unrest. That’s just math.”

In December, the National Economic Council invited sharing-economy and union leaders to the White House to discuss the lack of a safety net. “They were asking, ‘Where do we land on the spectrum between employment and exploitation?’” says Shelby Clark, the founder of RelayRides, who is now the executive director of Peers, an advocacy group for the sharing economy. Peers provides personal-liability protection for home sharing (most policies will kick you off or offer exorbitant bed-and-breakfast coverage if they find out you’re on Airbnb) and replacement cars to ride-sharing drivers after an accident. He’s working on getting a worker’s-compensation insurance policy, a car-insurance policy that covers both personal and Uber rides, and a way to transport your reputation among sharing-economy companies that you work for.

Clark isn’t confident that the government is going to provide any of the services for freelancers that corporations provide for their employees. However, Obamacare has been a key fuel for the sharing economy, allowing people to leave their jobs for freelance gigs. Most sharing-economy companies essentially use HealthCare.gov as their human-resources site. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen tweeted in October, “Perhaps the single biggest key enabler for the sharing/gig/1099 economy in the U.S.: Affordable Care Act of 2010, a.k.a. Obamacare.”

My own corporation doesn’t have a lot of resources available yet to protect itself. My car, three days later, is still being driven around by some mad Italian woman with no clue how to operate the transmission. But when she finally does show up at my house, it turns out that my driver’s-side door has only a slight dent. And after I go to the body shop and get an outrageous estimate, RelayRides’ insurance company sends me a check right away. The woman hit by the Italian writes me an email saying how impressed she was by the way it was handled. It all goes so well that I actually use RelayRides again. This time, I lend my car to a 23-year-old who is parking six different-colored Mini Coopers at the Griffith Observatory to propose to his Mini-loving girlfriend. His buddy returns a few hours later with the car and photos of the newly engaged couple. I may not make as much money as Hertz does, but I get to feel a whole lot better about it.