China’s strongest leader in years, aims to propel his nation to the top of the world order

The Oct. 27 profile of China’s leader Xi Jinping in the Shanghai Observer didn’t stint on praise. Readers of the dispatch, published by an online daily partly owned by a local chapter of the ruling Communist Party, learned that the 61-year-old President rises before dawn and toils late into the night. He is “bold and down-to-earth,” and “his work style is very rigorous, and his rhythm is very fast.” Within the space of a few hours, the writer revealed, Xi dealt with the Presidents of both Indonesia and Tanzania with grace and charm–a foreign policy natural. “Everyone present nodded in praise” at the Chinese President’s words, the profile said. A single humanizing touch was added: “Of course, like the average Chinese person,” the Shanghai Observer noted, “Xi Jinping’s busy day is not without humor and joy.”

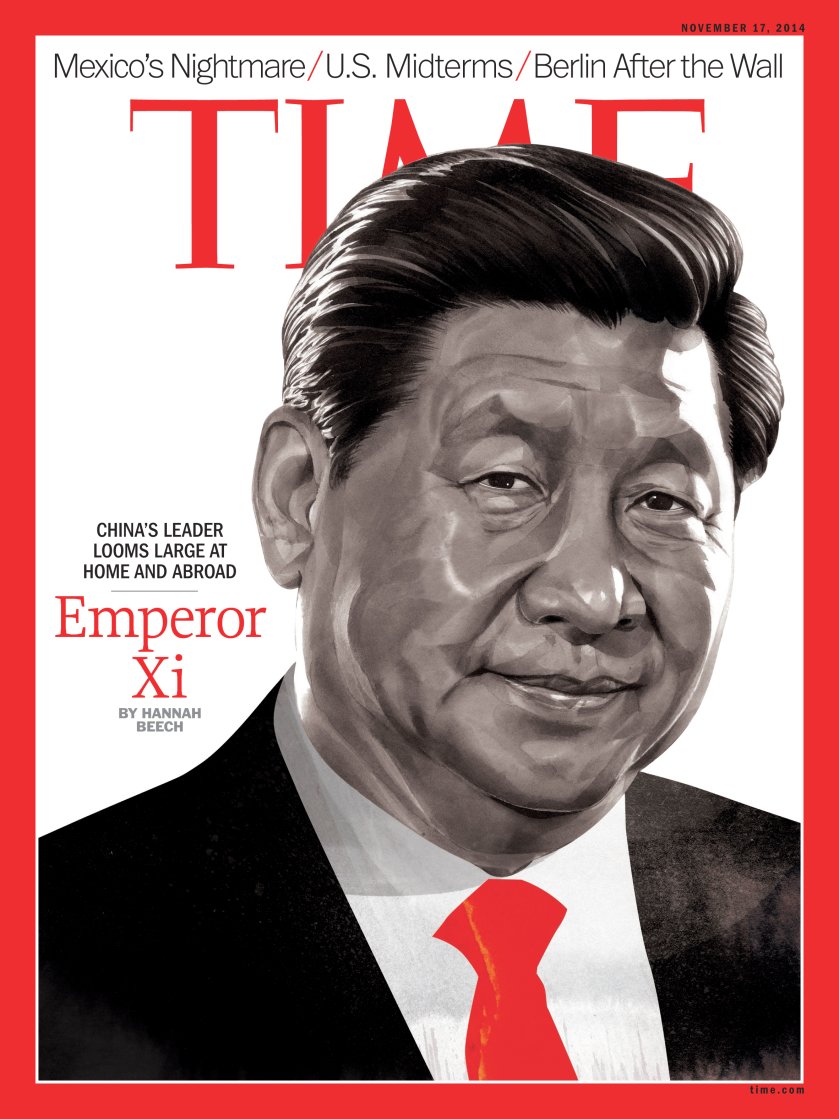

Since taking office in November 2012, Xi has consolidated power more rapidly than any other Chinese leader in decades–all, if the Shanghai Observer is to be believed, without misplacing his sense of fun. It is not too early to suggest that Xi will be China’s most consequential leader since Deng Xiaoping, the architect of the nation’s economic reforms. As the nation’s President, military chief and, most important, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi has upended the notion that the People’s Republic is ruled by a leadership collective. “In just two years, Xi Jinping has made himself into a strongman,” says Willy Lam, an expert on elite Chinese politics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “He has totally exceeded expectations.” The headline of an Oct. 21 online post in the People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, captured Xi’s place in history: “Mao Zedong made Chinese people stand up; Deng Xiaoping made Chinese people rich; Xi Jinping will make Chinese people strong.”

It is with an ascendant Xi that U.S. President Barack Obama–fresh from disappointing midterm elections in the autumn of his presidency–will meet this month at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Beijing. The Nov. 10–12 forum will be the pair’s first meaningful encounter since a confab at a California ranch last year, when Xi reiterated the need for “a new kind of major power relations” between the world’s two biggest economies.

The gathering in Beijing will be the Chinese leader’s big show, and the regime has used its authoritarian muscle to ensure a flawless event. To guarantee blue skies in the notoriously smoggy capital, factories have been idled and Beijing residents ordered to halt their work commutes. Waiters have been trained in exactly 484 steps to ensure that more than 73,000 guests receive their food within six minutes of its preparation. A perfect place setting has a purpose, and this one is no different: At APEC, Xi is expected to lobby a skeptical international audience for changes in the global financial architecture to give the East greater prominence. “He wants a new financial order,” says Lam, “with the Asia-Pacific and China at the center.”

A Man Apart

Like the surging nation he leads, Xi (pronounced Shee) radiates pride and ambition. His mantra, plastered on billboards nationwide, is “Chinese dream”–an amorphous catchphrase that encompasses an individual striving for personal riches and a collective campaign to restore the country to its rightful position atop the international order. “As Xi maneuvers to place China at the center of the world,” says Jerry Hendrix, a retired U.S. Navy captain and Asia analyst, “he is simultaneously moving to place himself at the center of China at a personal level unseen since Mao and Deng.”

Given how Mao-mania led to the Cultural Revolution and other horrors, China might be wary of personality cults. For decades since, the Communist Party has encouraged consensus building within its top ranks to avoid any one man’s capriciousness from holding sway. But Xi, the son of a party revolutionary, has proved a canny populist after a decade of the colorless regime of former President Hu Jintao. To garner public support, Xi lards his speeches with any number of rousing refrains: jingoist rhetoric, Marxist slogans and even Confucian quotations that could have landed the literati in jail during Mao’s era because of the Chairman’s notorious allergy to ancient wisdom. “We will never blindly copy the experience of other countries,” Xi said in an August speech, “let alone absorb bad things from them.”

Whereas his predecessor Hu faded into the background–a pale apparatchik surrounded by other gray-faced functionaries–Xi has bluntly asserted his authority. Rather than divvy up responsibility among the seven members of the ruling Politburo Standing Committee, Xi has taken direct command of influential committees, some newly formed, on national security, censorship, the Internet, military restructuring, foreign policy and economic reform.

Xi symbolizes a nation projecting greatness, but his homeland is struggling with slowing growth: the economy expanded by 7.3% in the third quarter, the slowest uptick in five years. A widening income gap, crippling corruption and environmental woes have led to dissatisfaction even from those who have benefited most from the greatest economic expansion of all time. Xi must wean China off an overdependence on exports and investment–and move the nation up the economic ladder by encouraging innovation and services. “At this critical moment of great changes and transitions, China is in dire need of a political leader who has the courage, sense of mission and wisdom to lead the country to its reawakening,” declared an August op-ed carried online by the China Daily, the party’s official English-language messenger, before naming Xi the man for the job. “All of Xi’s ideas and actions on cultural, military, political and economical reforms are meant to push China further along the road to rejuvenation.”

Born to Rule

If Xi carries a sense of manifest destiny about his homeland, his personal trajectory seems equally preordained. The son of Xi Zhongxun, a communist guerrilla who fought alongside Mao, he was sent to the countryside to atone for his elite background after his father fell victim to a leadership purge in the 1960s. Like the local villagers, the younger Xi lived in a cave in rural Shaanxi province, for seven years. “Life [at] the grassroots can strengthen your mind,” Xi recalled of the manual labor, fleabites and blisters in a 2005 interview with local TV. “Since then, no matter what kind of difficulties I encounter, as soon as I remember these experiences, I regain courage.”

As the tumult of Mao’s political upheavals dissipated, Xi slid back into city life, studying chemical engineering at the elite Tsinghua University and rising through party ranks in coastal areas profiting from market reforms. (His father was also rehabilitated and later championed economic experimentation and liberal politics.) Xi eventually married an alluring singer famed for her renditions of military tunes. Unlike other recent First Ladies who were rarely photographed in public, Peng Liyuan has traveled by her husband’s side on foreign trips, invariably outfitted in stylish Chinese labels. The couple sent their daughter to Harvard University–perhaps the true Chinese dream.

Yet this revolutionary princeling, as scions of party royalty are called, has also cultivated a common-man image. Since taking office, Xi has emerged from behind the vermilion walls of the Beijing leadership compound to stroll the capital’s alleyways and chow down on steamed buns. In a nation where officials are used to employing bag men, Xi pointedly carries his own accessories in some photo ops. (A picture of the President clutching his own umbrella, his pant legs rolled up to avoid a downpour, won China’s top photojournalism prize this year, even though the image was hardly artistically exceptional.) The carefully constructed persona–candid and approachable, despite the helmet of perfectly parted and dyed hair–even has a name: Xi Dada, or Uncle Xi. “This nickname makes him more like a man of the people,” says Pan Yuhang, an environmental-science major at Beijing Normal University, who held aloft a handmade sign welcoming Xi Dada to the campus in September.

Xi has so far declined unscripted interviews with major, independent foreign media. But he has promoted policies that are particularly popular among the 700 million or so Chinese who have attained or are striving for middle-class status. He has launched–and, more impressively, intensified–an antigraft campaign that has netted nearly 75,000 cadres in a country where endemic corruption has shredded the party’s reputation. (It hasn’t gone unnoticed that the crusade has also felled some of Xi’s presumed political rivals.) In a country experiencing the most frenzied urbanization in world history, he has vowed to simplify the paperwork people need to move from farms to cities. He has also pledged to loosen long-hated family-planning restrictions so that China can better prepare itself for a future filled with too few youths taking care of too many elderly. “Xi Jinping is the emperor of the bourgeoisie because it’s the emerging middle class that matters most in China these days,” says Kerry Brown, a former British diplomat who now heads the China Studies Center at the University of Sydney.

Given the middle class’s fondness for private enterprise, property and other capitalist notions, it’s become harder to justify communism as the most suitable ideology for modern China. So Xi has relied on nationalism to inspire and unify the masses. From the South and East China Seas to the Himalayas, Xi defends what he sees as China’s rightful borders. He has chafed at U.S. attempts to keep the peace in the Pacific, dismissing Obama’s talk of “pivoting” to Asia as nothing more than containment of China by another term. “Matters in Asia ultimately must be taken care of by Asians,” Xi said at an international security conference in Shanghai in May. “Asia’s problems ultimately must be resolved by Asians, and Asia’s security ultimately must be protected by Asians.”

China’s neighbors, most of whom are economically beholden to Beijing, worry about the country’s maritime expansion and military buildup. While Hu spoke of China’s “peaceful rise,” Xi has warned that the People’s Liberation Army needs to be on alert. “We must ensure that our troops are ready when called upon,” he told soldiers shortly after taking office, “that they are fully capable of fighting and that they must win every war.” New Chinese passports were issued the year Xi ascended to power that show boundaries conflicting with those claimed by eight other governments. China’s leaders insist they are not upping the ante, but they have not used multilateral forums to settle the disputes. Economic partners aside, Beijing has few true international allies. “China wants the status of being a superpower,” says the University of Sydney’s Brown, “but it doesn’t want the responsibility.”

The Nationalist Card

Xi has resorted to fulminating against an old bogeyman: the evil West, intent on subjugating China, just like it did 150 years ago when imperial powers exploited the enfeebled Qing dynasty. Last year an internal government memo circulated listing seven Western values and institutions that China must battle at all costs, including constitutional democracy, media independence, civil society and market liberalism. Even the “universal values” of human rights were seen as unfit for Chinese consumption. Instead, Xi has promoted the Communist Party above any other institution, including the Chinese courts and the constitution.

Just a couple of years ago, Xi had to tolerate Western disapproval. On a February 2012 trip to the U.S., before he became China’s leader, Xi received an official champagne toast from Joe Biden, from one Vice President to another. In his lengthy remarks, Biden blasted–diplomatically, of course–China’s habit of locking up dissidents, its pillaging of intellectual property and trade secrets and its undervalued currency. “Xi stood there with a Cheshire-cat grin on his face,” recalls Richard Solomon, a veteran East Asia hand at the State Department who attended the event. “But he must have been enraged–to put it in Chinese terms–at the real loss of face, and not giving him the kind of respect that he felt he deserved.”

Now the tables have turned. Obama may bring a long list of requests to Beijing this month–a rollback on Chinese cyberspying, more market access and better treatment of ethnic minorities–but Chinese state media have already been scaling back expectations for the U.S. President’s visit. A Nov. 5 online commentary in the People’s Daily criticized the U.S. for “double standards in the fight against terrorism” and warned Washington to tread lightly on trouble spots like North Korea and Beijing’s poor relations with Tokyo. Wang Fan, vice president of China Foreign Affairs University, was quoted as saying: “Such hot issues touch upon China’s core interests.”

Beyond geopolitics, Xi and Co. have unleashed a crackdown on foreign businesses operating in China, nailing them for antitrust violations, bribery and substandard products. Yes, domestic companies have been targeted too, but it’s hard not to see an antiforeign bias in the crusade, which has harnessed the state media. Everyone from Microsoft and McDonald’s to Apple and Audi has been shamed. A summer survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China found that 60% of respondents felt the welcome for foreign business had chilled, while the European Chamber of Commerce complained that it had “received numerous alarming anecdotal accounts from a number of sectors that administrative intimidation tactics are being used to impel companies to accept punishments and remedies without full hearings.”

For all of Xi’s populist charm and global ambitions, his tenure has also been marked by a brittleness at odds with the image of an aspiring superpower. Hundreds of Chinese who have dared to question the wisdom of the party have been locked up, most with no due process. Xi has tightened controls on the Internet, silencing even voices that parroted the party’s own modest reform goals. In tiny Hong Kong, the former British outpost that is governed by separate laws from the rest of China, Beijing has given no indication that it will consider the wishes of the thousands of residents who have taken to the streets to demand democratic concessions for their city.

The crackdown on dissent has reached ridiculous proportions. Over the past month, for example, Chinese security personnel have rounded up more than a dozen people in an artist’s colony outside Beijing. Some were taken away for posting articles about the pro-democracy protests shaking Hong Kong. Others were detained at a poetry reading. People who tried to help the detainees’ families were themselves picked up. “The arrested artists did not want to be martyrs and none of them tried to organize a rebellion,” says an artist surnamed Han, who does not want his full name used because so many of his friends are now in jail. “They just wanted to express themselves.”

A Clean Image

To Xi, such free expression and debate may be among the Western iniquities the party must guard against if it is to avoid the fate of the defunct Soviet Union. “Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse?” Xi asked in a December 2012 internal speech that was later leaked. “An important reason was that their ideals and beliefs had been shaken.” Perhaps the battle against independent thinkers also proves Xi’s innate conservatism, despite the hopes that he would follow in the footsteps of his more liberal-minded father. Or maybe it’s simply the mark of a man beset by the multitude of challenges that come with leading one-fifth of humanity. If Xi is clearly in charge of China, then it is he who will take the fall if the economy slows drastically and social unrest explodes. “Discontent [in China] is on the rise,” says Dan Blumenthal, director of Asian studies at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. “People are wealthier. The deal that was made–‘shut up, and you’ll get wealthy’–is coming to an end. They want a lot more than that.”

What the Chinese people are getting instead is a leader whose image is so controlled that little is left to chance. Earlier this year, a cartoon was released on a government-linked website featuring Xi–unremarkable in a Western context but revolutionary in a country where leaders are not to be made fun of, even gently. The Xi caricature was jolly-looking, with a pleasing belly and inoffensive gray-and-blue clothes. Then came the flood of analysis, presumably state-sanctioned, as to why this cartoon meant all of China should adore Xi Jinping. The Global Times, a patriotic newspaper, even wrote approvingly of the angle of Xi’s cartoon feet in an online infographic: “His wide-toed stance is deliberate to make the President seem more open to the people.”

A similar exhaustive outpouring followed the publication of last month’s Shanghai Observer story. But when Time tried to contact the author of the profile, the facade of journalistic credibility crumbled. An Observer employee admitted that the reporter’s name might be a pseudonym and that he had never met the writer. “His articles are always forwarded to me by someone else,” he said, declining to disclose who that sender was.

–WITH REPORTING BY GU YONGQIANG, EMILY RAUHALA AND MICHAEL SCHUMAN/BEIJING AND MARK THOMPSON/WASHINGTON