Can Uganda’s gay-rights activists stop the government from enacting another homophobic law?

At the entrance to a sprawling, open-air bar and restaurant in downtown Kampala, a large sign advertises what—six days out of seven—is on offer: music food massage. Inside, prostitutes in tight tank tops and miniskirts lounge on plastic chairs under the shade of a mango tree, waiting for customers. But for one night each week, the prostitutes take a break and this place of heterosexual commerce becomes the closest thing Kampala—a city of about 2 million—has to a haven for gay people.

At the bar, Kampala’s gay men, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender people (or LGBT) gather over bottles of the local Club beer to soothe rattled nerves and take refuge in a place where strangers do not glare at them with hostility. When the bar closes a few hours after midnight, most will go home to closeted lives, hiding their sexual identity from family, friends and employers. “When you are gay, life in Uganda is not good at all,” says transgender activist Joseph Kawesi, as she knocks back her third bottle of Club. “When I go home, there is a boy who keeps shouting, ‘You are gay, we are going to kill you.’”

Members of Uganda’s LGBT community have plenty of reasons to live secret lives. Over the past decade, Ugandan tabloids have mounted repeated attacks on gay people in the country, outing prominent figures and even calling for them to be killed. “Hang Them; They Are After Our Kids,” ran an October 2010 headline in Uganda’s Rolling Stone (which has no relation to the American magazine of the same name). The names, addresses and photos of “Uganda’s Top Homos” were printed inside. Three months later, one of the people named, prominent gay activist David Kato, was found bludgeoned to death in his home. A police investigation into the case concluded that the motive was either robbery or a personal dispute, even though Kato had complained about an increase in harassment during the preceding weeks. Other people whose names were published in the magazine were evicted, fired from their jobs and disowned by their families. Following the February 2014 enactment of a bill that allowed courts to sentence gay people to life in prison, a tabloid named Red Pepper printed a list of “Uganda’s Top 200 Homos.” Attacks on gay people climbed steeply at around the same time: Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG), an LGBT-rights umbrella group based in Kampala, listed some 300 cases of harassment and physical assault on LGBT people in 2014, up from a dozen in 2009, most of which were blackmail cases.

The rise in anti-gay sentiment has many gay Ugandans despairing of ever being able to walk down the street without fear of being spat upon, cursed or even physically attacked. “This is not a life,” says Kawesi. “This is existing despite the odds.” The baby-faced 31-year-old still has nightmares about the night, 21⁄2 years ago, when she says police officers dragged her out of her home after a tip-off that she might be gay. She says the officers beat her, then raped her with a club. Hospital records, friends and her lawyer attest to the physical damage, but Kawesi decided not to push for a prosecution of the officers she says assaulted her because she did not believe she would be able to prove their involvement in court.

The gay-baiting in the tabloids has not happened in a vacuum: Over the past six years, Uganda’s religious leaders and politicians have embarked on a campaign to rid their country of homosexuality no matter the cost—and the cost has been high. A few months after Uganda’s parliament passed the anti-homosexuality bill, many Western donors stopped funding aid programs. The World Bank postponed a health care loan worth $90 million, while the U.S., Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway collectively suspended or redirected aid worth another $50 million. The U.S. imposed visa restrictions on high-ranking officials and canceled a regional military exercise. European manufacturers threatened to pull out of the country, worried about a backlash from consumers back home.

Uganda’s threatened gays are hardly alone in Africa. Legislated homophobia is on the rise across the continent, even as LGBT people have made historic gains elsewhere in the world. According to a 2013 report by the Pew Research Center, a large majority of North Americans, Latin Americans and residents of the European Union now accept homosexuality. Same-sex marriages are legal in 19 countries, with the U.S. Supreme Court about to weigh in on the issue. And on May 22, heavily Catholic Ireland became the first country to legalize gay marriage by referendum. But in Africa, where the vast majority of people—98% in Nigeria, 90% in Kenya and 96% in Uganda, Senegal and Ghana, according to the Pew poll—say homosexuality is unacceptable, many religious leaders have watched that progress with alarm. Conservative politicians have also sought to protect their nations from what they see as a Western import by drafting anti-gay legislation even more draconian than the colonial-era sodomy laws that remain on the books in many African countries.

“Over the last five years, we have seen more laws being proposed and being passed into law in Africa,” says Laura Carter, Amnesty International’s adviser on sexual orientation and gender identity. “Even in places where the laws have not changed, enforcement has increased.” Thirty-four of 54 African nations currently criminalize homosexuality. According to Amnesty, South Sudan, Burundi, Liberia and Nigeria have implemented increasingly punitive penalties for people who engage in homosexual acts. Gambia now calls for life in prison. Mauritania, Sudan and parts of both Somalia and Nigeria permit courts to impose the death penalty in certain cases for individuals found guilty of same-sex activity.

Africa is not the only part of the world to witness wide-scale intolerance for gay people, even as much of the world becomes more accepting. The Pew survey found high rates of hostility to homosexuality in parts of the Middle East and Asia, and increasingly in Russia.

The Pew survey also describes how intolerance for homosexuality tends to be more intense in communities where there are high levels of religious observance, and African nations stand out as some of the most observant in the world. Religious conservatives, Christian and Muslim alike, may be losing ground with the public on LGBT rights in the West, but in Africa, where church and mosque remain the cornerstones of society and politics, anti-homosexual campaigners are determined to hold ground. Ty Cobb, global director for the Washington-based Human Rights Campaign, an LGBT-rights advocacy group, says the growing backlash against homosexuality in Africa over the past several years is a proxy war in the cultural conflict that is being lost by the evangelical Christian movement in the U.S. and beyond. “We are seeing a lot of conservative American influence playing out in this debate,” says Cobb. J. Peter Pham, Africa Center director at the Washington-based Atlantic Council policy institute, notes that given the high degree of intolerance for homosexuality among African nations, politicians have been able to consolidate support by targeting LGBT communities at home. “If you’re a cynical enough politician to exploit it, it’s a winning issue. And even if you’re opposed to it, unless you’re a courageous person prepared to stand on principle, your opponent is going to mow you down with it.”

Outside Influences

Nowhere is that toxic brew of african conservatism, American evangelical influence and political gay-baiting more visible than in Uganda, a landlocked country on the shores of Lake Victoria. For decades, Uganda’s small LGBT community survived in the shadows, with the majority of gay people remaining closeted. Ugandan society at large tended to leave alone those they suspected of being gay, says lesbian activist Clare Byarugaba. That started changing in 2009, when conservative Ugandan pastors became concerned about what they saw as the growing influence of liberal Western values in Uganda and what they feared would be the accompanying acceptance of homosexuality in Uganda. They invited a trio of American evangelicals to Kampala to lead a conference on what they termed “family values” and conduct a seminar titled “Exposing the Homosexuals’ Agenda.”

In the U.S., the three pastors—Scott Lively, Don Schmierer and Caleb Lee Brundidge—were members of a Christian movement that preached against homosexuality and promoted so-called gay-conversion therapy to what had become a rapidly dwindling audience. In Uganda their visit had the impact of “a nuclear bomb,” Lively wrote in a blog post in March 2009 about his trip. As the Massachusetts-based founder of Abiding Truth Ministries, a Christian organization hostile to homosexuality, Lively had spent nearly 20 years fighting what he called the gay community’s Marxist plot to break down the nuclear family model and destroy civilization.

Over the course of three days in March 2009, Lively preached at large churches across Kampala. He visited schools, colleges, community groups and parliament to speak about what he called the “gay agenda.” He gave interviews to secular and religious radio stations, appeared on TV and spoke to reporters at national newspapers. His explicit warnings of a homosexual conspiracy to recruit Uganda’s children to replace “marriage-based society” with a “culture of sexual promiscuity” resonated in a population already fearful of losing cultural traditions to the pull of global modernity. “They have taken over the United Nations, the United States government and the European Union,” he warned one congregation. “Nobody has been able to stop them so far. I’m hoping Uganda can.”

Not long after Lively’s visit, Ugandans started seeing the flamboyant uncles and suspiciously single aunts who had once been pitied as social outliers as legitimate targets for persecution, according to Byarugaba. “All of a sudden people who had been O.K. with LGBT people before heard these lies and began to see us as a threat to children, to traditional marriage and to society,” says Byarugaba, who sports a porcupine-like array of tiny, blond-tipped dreadlocks. She realized it was time to come out and take a stand when, a few weeks after Lively’s visit, her church leaders asked her to sign a petition demanding the death penalty for gay people.

Even without Lively, Uganda would have eventually gone in the same direction, says Pham of the Atlantic Council. African church leaders, he notes, were becoming alarmed by what they saw as European Christianity’s increasing acceptance of homosexuality. Uganda, with its long history of conservative church activism, led the charge. Lively and his colleagues just provided a blueprint for achieving a homosexual-free state, one that Uganda’s church leaders and politicians followed nearly to the letter.

In 2009 conservative pastors started showing their congregants pornographic images downloaded from the Internet of sadomasochistic acts between men—a move borrowed from the U.S. anti-gay movement that focused on minority sexual practices to stoke fear of homosexuality. Six weeks after Lively’s visit, Uganda’s U.S.-educated Finance Minister David Bahati introduced a bill to parliament calling for the death penalty for gay people, even though colonial-era laws—rarely enforced—already banned homosexual sex. “The pre-existing laws were not sufficient,” says Minister for Ethics and Integrity Simon Lokodo, who is also a Catholic priest. “You had to catch someone in the act, which was very difficult. We had to improve the penal code, to address recruitment, promotion and exhibition of homosexuality.”

Analysts say the anti-homosexual movement in Uganda was, to a large degree, a cynical attempt to gain populist political support at the expense of a vulnerable minority. Parliament debated Bahati’s 2009 bill at various intervals but only passed it in December 2013; a few months later, President Yoweri Museveni publicly signed the bill into law. “The only reason the President signed the Anti-Homosexuality Act into law was to get public support in advance of the 2016 elections,” says Lindsey Kukunda, a Ugandan pollster who works for TrackFM, a company that canvasses public opinion via national radio stations. “That law was nothing but politicians exploiting their power to attack a minority group because the majority doesn’t care or even understand.”

Lively, for all his boasts about the impact of his visit to Uganda, wrote in a 2010 statement that he was “mortified” that Bahati’s Anti-Homosexuality Act included the death penalty, and he lobbied to have it changed. He endorsed a revised version that called for life imprisonment for “aggravated” homosexuality, a crime that includes engaging in homosexual acts more than once, or with a minor, or while knowingly being HIV-positive. Lively declined to speak to Time on the issue, but through his lawyer disputed as “uncorroborated and self-serving” any evidence that suggests violence against homosexuals rose in the wake of his visit, or the subsequent implementation of the law. “Scott Lively has continually and strongly condemned all violence against homosexuals,” writes his lawyer, Horatio G. Mihet, via email.

Standing Up

As the anti-homosexuality act worked its way through parliament, Uganda’s small but vocal LGBT community decided to fight back. In 2012 the New York City–based Center for Constitutional Rights, a nonprofit legal advocacy organization, brought a civil case in a U.S. federal court in Boston against Lively on behalf of SMUG, the Kampala-based LGBT advocacy group. The case argues that Lively violated international law through his “involvement in anti-gay efforts in Uganda, including his active participation in the conspiracy to strip away fundamental rights from LGBTI persons” under the Alien Tort Statute, a law that gives survivors of human-rights abuses the right to sue the perpetrators in the U.S. Lively tried to have the case dismissed on First Amendment grounds, but the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston denied his last petition in December. The case is likely to go to trial early next year. Lively’s lawyer, Mihet, says, via email, that the case is unwarranted. “The notion that Africans cannot think for themselves and independently enact their own public policies on homosexuality is both racist and offensive. The sovereign people of Uganda, and their duly elected parliament, are responsible for Uganda’s laws and policies.” In 2012, Lively defended himself to the New York Times, saying, “I’ve never done anything in Uganda except preach the Gospel and speak my opinion about the homosexual issue.”

The case may be difficult to prove, but the fact that SMUG has been able to take it all the way to the U.S. federal courts is still a victory, says Diane Bakuraira, a SMUG activist. “It provides a check for those evangelicals who want to preach homophobia and lets them know that it is no longer acceptable,” says Bakuraira. Lokodo says the case is nonsense and that Lively provided a valuable service to Uganda. “He helped us see the threat that homosexuals pose to our culture, our society and our families, so what is the problem?”

Lokodo’s boss is certainly not backing down. On Feb. 24, 2014, President Museveni signed the Anti-Homosexuality Act into law, declaring to a gathering of international journalists that homosexuality was an example of the West’s “social imperialism.” Uganda’s courts overturned the bill in August on a technicality—there was no quorum the day it was passed in parliament—and many LGBT activists and political analysts privately say that it might have been a face-saving measure for the President to do away with a law that had brought on an international backlash and continued sanctions. The old colonial-era law against homosexual practices, however, is still in place, and now that overt homophobia has taken root in Ugandan society, every member of the LGBT community is a potential target. “Those evangelicals planted a bad seed,” says Hakim Semeebwr, a 26-year-old drag queen who goes by the name Bad Black. “The politicians watered it. Now that it has taken root, it can grow for years.”

A Renewed Threat

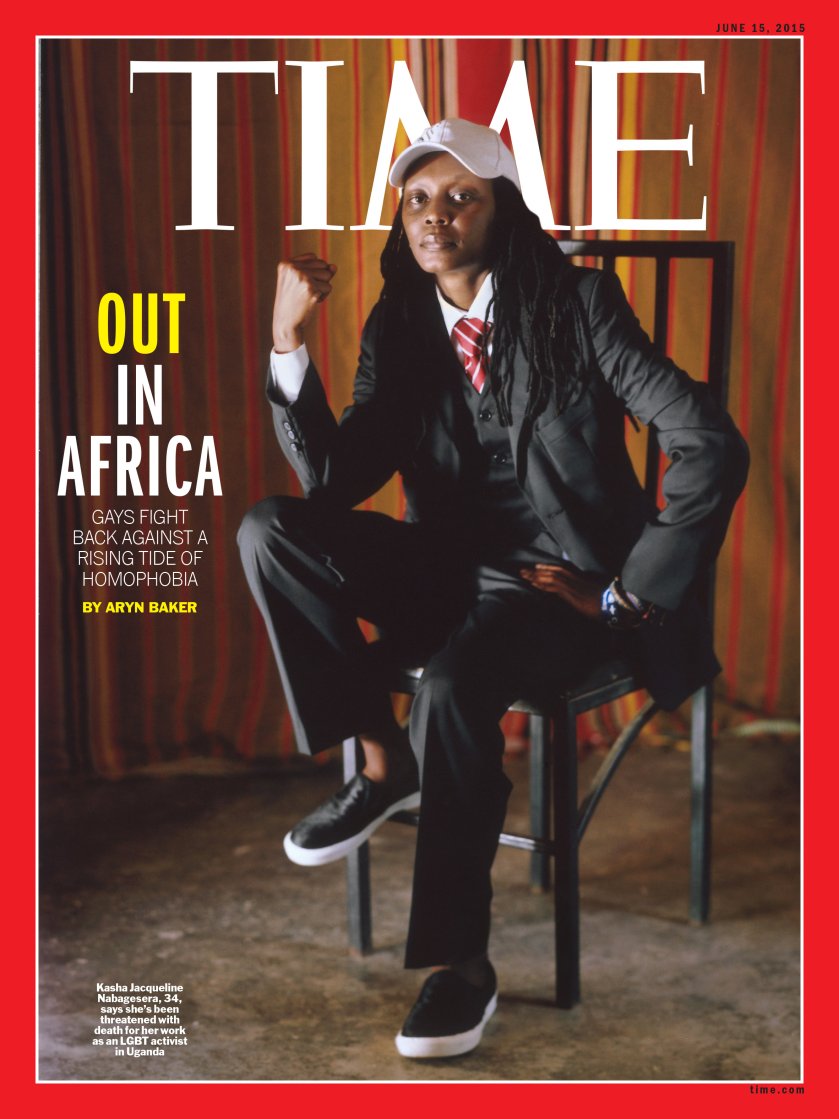

At his office at the ministry of ethics and Integrity, Lokodo flips through the spiral-bound draft of a new bill that was submitted to parliament in November 2014, less than three months after the Anti-Homosexuality Act was overturned. It is tentatively titled the Prohibition of Promotion of Unnatural Sexual Practices Act, and, according to LGBT activists who have seen copies, it is even more draconian than the original act. “Promotion” in the context of the new bill includes publishing materials in support of Uganda’s gay community or even providing health care to homosexuals. Lokodo, who stepped down from his leadership position in the Ugandan Catholic Church to take up the government post six years ago, wants to see the new bill criminalize activists like Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera, who published and distributed Bombastic, a free magazine focused on the personal stories of Uganda’s gay men and women, in December. “If you are homosexual it is unfortunate,” says Lokodo. “But to go out on the streets of Kampala and say ‘I am gay’ is the same as saying ‘I am a thief or a murderer.’ It’s like handing yourself to the police for arrest.”

Uganda’s outspoken community of gay activists says it will fight the new law as it fought the last one—through the courts, by raising awareness and by lobbying for international support. They are also hoping to find allies among more liberal Ugandans disgusted by the ugly rhetoric that accompanied the introduction of the last law, says Bakuraira of SMUG, noting that while most Ugandans publicly supported the bill, many were shocked and alienated by the real-world repercussions.

For all the challenges facing gay people in Uganda, Bakuraira, who tracks homophobic media attacks, has noted an incremental shift in public opinion over the past six months. Newspapers are starting to publish positive stories about gay Ugandans, like when Harvard’s law school honored Nabagesera in March for her activism on behalf of Uganda’s gay community. Martin Ssempsa, the Ugandan pastor who was Lively’s most passionate acolyte, seems to have fallen out of public favor ever since he was convicted in 2012 of conspiring to tarnish a rival pastor’s reputation by falsely accusing him of engaging in homosexual behavior. Ssempsa was given a sentence of 100 hours of community service and was ordered to pay a fine of around $350 after being found guilty of making a false accusation. His 2,000-seat church now stands empty and unused. In August, tabloids outed Joanita Warry, the captain of Uganda’s national women’s rugby team—but she retained her leadership position. And, according to Byarugaba, activists are finding allies in unexpected places, like in the police force. Now that the Anti-Homosexuality Act has been overturned, some of the Western-mentored senior officers in Kampala are beginning to understand that their duty is to protect Uganda’s LGBT community from harm as long as they are not breaking laws.

U.S. visa bans imposed on several outspoken anti-homosexual Ugandan officials in June 2014 have succeeded in tamping down public rhetoric, says activist-publisher Nabagesera. And publications like Bombastic helped by offering an alternative narrative to the lurid tabloid exposés. A new generation of young overseas Ugandans who are increasingly exposed to the more tolerant attitudes of the West is also helping. The way Byarugaba sees it, the so-called kill-the-gays bill, as the Anti-Homosexuality Act was dubbed in the popular press, had the unintended consequence of bringing homosexuality out of the shadows and into the public square, ultimately weakening long-existing taboos. “There is a discussion around homosexuality now that wouldn’t have happened without the anti-gay movement,” she says. “It is no longer something people are afraid to talk about. They are saying, ‘Who are these people the government is focused on?’”

Those changing attitudes are but a small, bright spark in an otherwise dark reality for LGBT people in Uganda. As public rhetoric mounts around the soon-to-be-proposed new anti-homosexuality bill, gay people in Uganda are bracing for a new spate of homophobic violence. And elsewhere in Africa, leaders have recently been openly hostile to gay rights: Kenya’s Deputy President William Ruto told a church congregation in May that there was “no room for gays” in the country. Gambian President Yahya Jammeh threatened to slit the throats of gay men the same week.

Nonetheless, lawyer Ladislaus Kiiza Rwakafuuzi, who has taken on many LGBT cases, believes that attitudes will eventually change, both in Uganda and in Africa. “When something is in the public domain, it is no longer taboo. The more of these laws they bring, the more they are watering down the fear of homosexuality. Contrary to what was expected, people are becoming more tolerant.”

Semeebwr, the drag queen, agrees that despite the drawbacks, the constant exposure has somewhat helped the cause. “We didn’t want to be outed; it caused a lot of problems,” she says, noting that her own promising career as a male television presenter was cut short when one of the tabloids exposed her sexual identity in December. “Ugandans, they had something in their heads that gays are sick, cursed, abnormal and not African. Now that we are out, they can’t deny we are Ugandan. They can’t deny that Africans can be homosexual too.” —with reporting by Naina Bjekal/London and Robin Hhammond/Kampalan