Part 1

The Time of Their Lives

“What’s the benefit?”

This is one of Don Draper’s favorite questions. When you’re trying to sell people something, what are you really selling them? Answer: not the product, not the thing itself. What people buy is the pleasure they hope to experience, the relief from a fear they want to assuage, the answer to an aching they long to satisfy. What you buy is the benefit; the product is only a means of getting you there. Or, as Don tells his protégée Peggy Olson: “You are the product. You, feeling something.”

This thing the advertising man knows. You don’t buy a Hershey bar for a couple of ounces of chocolate. You buy it to recapture the feeling of being loved that you knew when your dad bought you one for mowing the lawn. (Or, if you’re Don, the fleeting pleasure from the candy bar you received after one of the hookers in the whorehouse where you grew up tipped you for rifling her john’s pockets.) You don’t go to Burger Chef for a hamburger; you go there to reassemble your family around a table as the centrifugal forces of life spin you apart. You don’t buy a Kodak Carousel slide viewer; you buy yesterday. As Don tells Kodak’s executives at the end of Mad Men’s first season, in one of the show’s most poignant and true moments: “It’s a time machine.”

So this is what we need to ask about Mad Men before we ask anything else. What’s the benefit? It’s a show about advertising, of course. (The “Mad” is short for Madison Avenue, the center of the advertising business.) It’s a show about sex and gender roles. It’s a period drama, a historical tour of upheaval. It’s a serial about secrets: stolen identities and secret pregnancies and office intrigue. It’s a love story, and sometimes a hate story. That’s the literal, pitch-meeting description—what you might say to someone who had never watched the show before.

But what is it really?

Well, let’s start with Don’s answer. Mad Men is a kind of time machine, but it’s a complicated one. It doesn’t go in only one direction. You start watching and it takes you to the past—early 1960—when you can smoke in any restaurant and doctors are just starting to prescribe the Pill. It moves forward: the Kennedy-Nixon campaign, Camelot, the Moon landing. But it also transports you from there to Don’s childhood as Dick Whitman in the Depression. It flashes to the Korean War, when the aimless orphan seizes the chance to reinvent himself, Gatsby-like, by stealing the identity of a fallen comrade (killed in an accident involving, natch, a cigarette lighter). It reminds us that the past has its own past. It moves, as Don says of the Carousel, “backwards and forwards.”

At the same time, Mad Men is very deliberately a story about our present. Creator Matthew Weiner is notoriously exacting about the show’s immersive period detail, yet surprisingly, as he explains in a series of interviews in 2014 while making the shows final season, he’s highly conscious of current events when he writes. When sketching the mood of the later seasons, set amid the assassinations and upheaval of the late 1960s, he says he was thinking of present-day America. “People were exhausted and terrified by the economic disaster of the last few years,” Weiner says. “They had low self-esteem and they were anxious about our place in the world.”

But maybe Mad Men’s most distinctive function is that it’s a time-lapse machine. Its most simple but radical premise has been to say: Here is what it looks like, how it feels, for ten years of life to pass. (Though the show could still flash forward before it ends—it’s not as if Weiner is telling—it’s run from 1960 to 1970 so far.) Most TV series distend time, deny it, cheat it. M*A*S*H took 11 years to fight a three-year war. Bart Simpson remains in grade school even though, as a character born in 1987, he is old enough to be his own father.

Mad Men, on the other hand, has covered about a decade of its time in about a decade of our own. We see hair grow longer, hemlines shorter. Paul Kinsey’s blazers give way to Stan Rizzo’s fringe jackets. Weiner has talked often about Don being a representation of American society, steeped in sin, haunted by his past but always asking the question: Why am I doing this again? Sexual liberation and feminism arrive, but the show is deeper than the sex—it’s about human experience and human nature and time unfolding. The children grow up (including four—count ’em, four—actors playing Bobby Draper). The colors get more saturated, the social mores more extreme. The cultural power shifts toward youth. The creatives are pitching TV storyboards, not text-heavy print ads. Characters get prosperous, get fat, get lost. It’s a potent effect: Just like in life, you don’t notice the gradual changes until you look back and—holy cow—how far have they come? How far have we? Where has the time gone, besides into the creases of our foreheads?

The last time I talked to Weiner, in December 2014, he was dealing with the passage of time physically: cleaning out his memorabilia-laden production office. (“There are a lot of liquor bottles! I don’t know what I’m going to do with it.”) Mad Men’s finale was already locked down by then. He, naturally, was not saying much about it—except that he hopes it feels like an ending.

“There’s not going to be a lot of flashing back to earlier in the show, which I know was really delightful for people in Breaking Bad,” he says. “But we tried to leave everybody in a place where you’d say, ‘Okay, that’s where they are. I think I know what their future’s going to be like.’ I’m an entertainer, and I wanted a sense of closure. But it’s hard, because my personal take on that is different from other people’s. I apologize for that in advance.”

Though there’s a certain breed of fan that expects Mad Men to end with dramatic closure—Don falls out of a skyscraper as in the title sequence, or turns out to be 1971 airline skyjacker D.B. Cooper—the show has always asked us to accept a degree of uncertainty. In season seven’s “The Strategy,” Don tells Peggy that in order to be the boss, she has to believe in her idea even though there’s no way she can know there’s not a better one. “That’s just the job,” he says. “What’s the job?” “Living in the not knowing.”

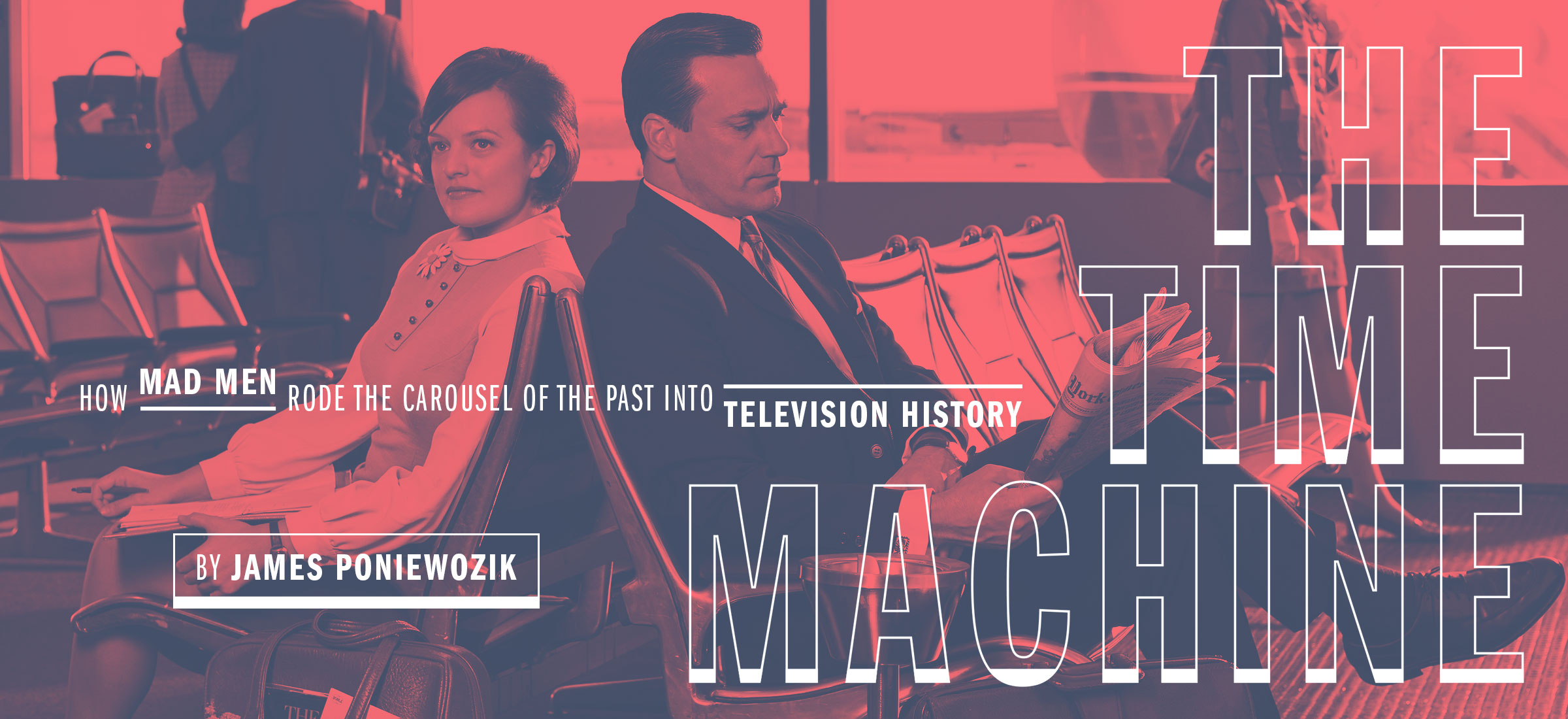

We too may have to live not knowing every last detail of what becomes of our Mad Men family, after the calendar turns over and the cameras stop. Maybe even the actors who play them will. “At the end of the day,” says Jon Hamm, who was interviewed with the rest of the cast during production in 2014, “what I hope for Don, and maybe the viewer does too, is that he be able to find some measure of peace with not only who he is and who he was but who he wants to be.” And Peggy? “We know what happened to those women in advertising,” says Elisabeth Moss—referring to ’60s ad women like Mary Wells Lawrence and Jane Maas who went on to become leaders in the field. “I definitely see her as one of those women who’s still working in their seventies and doing what she loves.”

Mostly, cast and crew are wistful. Says Christina Hendricks, “We all carved our initials into a tree at Base Camp [the cast’s hangout area during production] on the last day.”

“Part of my intention when I pitched the show,” Weiner told me on my earlier visit to the set, “was, Wouldn’t it be amazing to do 10 or 12 years of these people’s lives, have the actors age that amount? And immediately, no matter how many bad things happen that first season, you will see Peggy and have nostalgia for her first day at work because you knew her then. That’s why I love that definition [from the “Carousel” scene], about nostalgia being the pain from an old wound. There is a pleasure in sort of picking at that.”

The pleasure’s been all ours.

Part 2

The New Frontier

Back to the beginning: set the time machine for January 1999. American viewers are witnessing one of the biggest changes in TV since the pictures started coming in color: the premiere of HBO’s The Sopranos. Tony Soprano is a bastard—not a cartoon wiseguy with his edges sanded down for the tube, but a selfish, sociopathic mobster who cheats on his wife, has his friends whacked, and kills with his bare hands. But he’s also complex, sympathetic, even funny. We don’t have to like Tony, but The Sopranos invited us to understand him.

The show, simply and suddenly, transformed TV. It didn’t just prove that cable could be as good or better than the old broadcast networks. It showed that television could have the same ambitions and complexity as great movies did. At a time when Hollywood itself was concentrating on big-budget spectacles, The Sopranos and the cable shows that followed it were the equivalent of the auteur revolution in the movies of the 1970s, embracing layered narratives and moral ambiguity, and often speaking in idiosyncratic voices.

Matthew Weiner was not a part of this revolution just yet. A film school graduate from the University of Southern California, he had ended up where so many ambitious cineastes did and still do: writing one-liners for sitcoms. The same year that The Sopranos began proving that TV could be art, Weiner was working on CBS’s Becker. Like many of the suits at Sterling Cooper—say, Ken Cosgrove, writing allegorical science fiction after a long day selling accounts—Weiner had landed a job, but he wanted something more.

So in his off-hours, Weiner began writing a story about another dissatisfied man who seemed to have it all. Weiner wanted to make a period drama with a difference. He set the story in advertising, a field that, in the early ’60s, was going through a revolution: moving from earnest to ironic, drawing inspiration from and co-opting youth culture and its rejection of the past, all the better to sell new stuff. Admen of the time were corporate soldiers but saw themselves as rebels, even artists—not unlike TV writers.

But one thing that would distinguish Mad Men from its inception was that, title aside, it wasn’t just about the men. As he researched his script, Weiner was also reading up on mid-century feminism: Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl. “They’re two sides of the same coin,” he says. “One of them is about women at home being miserable and the other is how do you turn your job into a life as a single woman?”

At the same time, Weiner, born in 1965, drew on memories from his childhood, when his mother went back to law school, then never ended up practicing. “Before I ever heard the word patriarchy,” he says, “I met all these moms just like my mom, who had advanced degrees and were living in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, in a beautiful wooded house and were driving the kids to school and were bored as s—.” From all this sprung Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss), trying to take control of both her career and her sexuality; Joan Holloway (Christina Hendricks), the savvy bombshell born a little too early to have had Peggy’s options; and Betty Draper (January Jones), the model turned not-quite-model-mother unloading her frustrations in the form of BB pellets at a neighbor’s pigeons.

The pilot script made the rounds—to HBO, among other places—but kept coming back, rejected, to Weiner’s desk. It did land him a writing job under Chase at The Sopranos, where Weiner developed a feel for that show’s mix of pulp entertainment and artistic flights of fancy. Among his writing credits for the series were “The Test Dream,” in which Tony’s anxiety over a mob-and-family crisis resolves itself in a highly symbolic fantasy sequence, and “The Blue Comet,” the blood-spattered second-to-last episode in which Tony’s gang war with the New York mob comes to a head.

The Sopranos was in part a triumph of timing: It came along in a period when HBO was committed to jump into serial drama and had few preconceptions about what its shows had to be like. By 2006, a similar window was opening at AMC, which, not unlike HBO once upon a time, was a cable channel that people thought of as a place to watch movies. AMC’s management was now thinking the channel could build on its brand with compatible originals. Maybe a much-talked-about-but-often-passed-on script that had its own resonances with classic movies—The Apartment, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, director Douglas Sirk—could fill the role? (Even Mad Men’s opening credits eventually recalled the snappy Saul Bass titles from Anatomy of a Murder and North by Northwest.)

AMC gave Weiner a deal, and also a rarer gift: low pressure. “We wanted to build premium television on basic cable,” says network president Charlie Collier. “It didn’t need the biggest, broadest rating from day one. The question was, did it bring distinction to the brand?” For a network just looking to get on the cultural radar, Mad Men did not have to be huge; it just had to be good.

This was fortunate, because there was one thing The Sopranos had that Mad Men didn’t: the Mob. That is to say, a drama about the work and love lives of white-collar advertising executives didn’t have a built-in popcorn-entertainment hook that fed the show with life-or-death stakes. There were no whackings or barrages of gunfire. In an early episode, ambitious junior executive Pete Campbell (Vincent Kartheiser) shows off a hunting rifle that he exchanged one of his wedding gifts for. As the show draws to its close, it has yet to go off. (Take that, Chekhov.)

If The Sopranos aspired to the level of movies, Mad Men aspired to the level of literature. The first season—which premiered just a month after The Sopranos went off the air—played like newly unearthed Updike or Cheever stories, little tales of love and despair in the office towers and suburbs of 1960. “The show has never been a procedural in any way,” says star Jon Hamm. “It’s not like we have to get to the pot of gold or solve the mystery or kill the bad guy or anything like that.”

Instead, the show would trust in the power of style, subtlety and, above all, secrets. Weiner conceived his protagonist as a handsome, successful but rootless man, trying to force himself into the role of a sophisticated executive and stable family man despite his hardscrabble, peripatetic past. Dick Whitman, future adman, solved the problem of his miserable life by rebranding himself.

It was, on one level, a classic story of self-reinvention and -deception. Don’s was a story about how the men who made America made themselves. “It’s in our DNA, these picaresque figures,” Weiner says. “I started with Rockefeller and Bill Clinton and Sam Walton and any biography I could read, Lee Iacocca—people who came to be leaders in this country. All of them came from rural poverty and none of them talked about their childhoods, or they lied about them.”

As the series evolved, it would add secrets. Big ones, like the fact that Peggy had a baby and gave it away just as her copywriting career was launching. Minor ones like whether the advertising agency had added a second floor to its offices before season five. All of this worked: The cultivated sense of mystery created an air of intense speculation in a show that was not about monsters or dragons but advertising and infidelity. Fans scrutinized its preseason poster art and its famously inscrutable “Next week on Mad Men” promos for clues as if they were the cover of the Sgt. Pepper album.

It’s the little things that would loom big on Mad Men. “I like the suspense of everyday life, quite honestly,” Weiner says. “There’s no one in the world today who sees an unidentified number on their cell phone and doesn’t have their heart racing.”

Part 3

The Little Things: Writing History into the Wallpaper

“I could write you a couple of paragraphs on the cigarette butt,” Dan Bishop, Mad Men’s production designer, tells me, in winter 2014, while the crew is shooting the seventh season. Weiner’s secrecy—about everything from the year a new season is set in to the office furnishings—is a running joke, yet it’s understandable in a way; the stars of Mad Men include the style, the fashions, the details, which not only provide realism but provide clues to character and illustrate the show’s philosophy of history.

Those butts, for instance. The actual cigarettes are herbal: they stand in for both tobacco cigarettes and joints, and give the production an appropriately weedy smell when the actors fire them up. I mention offhandedly to Bishop that I’ve noticed all the elegant ashtrays with cigarette butts artfully lying flat in them, and he seems chagrinned—because as he realizes, they should not be lying so neatly. “When you stub them out”—he smacks a table with his hand, like he’s crushing one out—”they’re standing up, like that. So when you see a tray of cigarette butts laying flat, we’ve blown it.”

On Mad Men, see, perfection means that nothing should be too perfect. One mistake that period dramas often make, for instance, is to have every set look like a design-magazine shoot from whatever the year is. The 1960s will look like “the 1960s,” loaded up with Eames furniture and Twiggy couture. The first time I toured Mad Men’s set, before the third season, I noticed that many of the knick-knacks and furniture in Don and Betty’s suburban Ossining, New York, home looked like they could have been from decades earlier.

And that’s how Mad Men wants it. When most people buy a house, they don’t burn their old possessions and buy entirely new ones. There are keepsakes and hand-me-downs and heirlooms. Look at your own house: Did you buy all your furniture this year? The clothes in your closet?

It’s partly about verisimilitude, yes. Weiner, and thus his staff, are fixated on nailing the details to a granular level. There aren’t just vintage Selectric typewriters on set: If you see a stack of typewritten pages on a desk, those have been typed—not printed on a computer, but typed, even the pages stacked underneath. The theory is: Even if the audience never sees it, the actors will. The Rolodexes are filled with actual vintage cards with KLondike-5-style numbers. (The production department has been an excellent customer for L.A.’s vintage shops, not to mention Craigslist and eBay.) When fruit bowls were stocked, Weiner vetted the apples and bananas—because the fruit at the time was smaller than today’s hypertrophied produce. Actresses were discouraged from working out too intensely, because the 1960s had some meat on its bones.

Beyond simple period accuracy, Mad Men is acting out a philosophy, handed down from Weiner, that informs its entire approach to history and character. A story set decades ago, it believes, is also about the decades that came before that. Just as we flash back to Don’s impoverished life in the 1930s, or his wandering days in California, so too is everything we see in Mad Men’s present shaped by an earlier America: by the fear of Depression, the horror of war, the desire for something better for your kids. It’s Conrad Hilton in season three, building an international empire and dreaming of a hotel on the moon—yet driven by his memories of growing up in rural New Mexico when it was still a territory. It’s Betty Draper’s father, growing senile in 1963, pouring Don’s expensive alcohol down the sink because he thinks it’s still Prohibition.

So a house on the set of Mad Men has ghosts. Think of Bobby Draper in season six, tearing at his bedroom wallpaper to get at the wallpaper underneath. Both in script and in style, Mad Men treats history as a palimpsest, rewritten and rewritten on the same sheet of paper so that you can still read traces of the earlier drafts. There is always wallpaper under the wallpaper.

Or when there isn’t, it means something. Don and Megan’s Upper East Side apartment, for instance, is brand-new: the brushed-perfection, space-age-jet-set, swanky pad of a young bride and her older husband, looking to erase the past (again) and start over in an urbane, postwar, white-brick high-rise. Or take Roger Sterling’s blinding-white office, with its Op Art, its gleaming chrome and enamel, and its futuristic furniture—another environment for an aging, death-denying roué, his design choices being made for him by a younger wife. It contrasts him with, say, Bert Cooper, the idiosyncratic, Japanophile, Ayn Randian capitalist, his office outfitted with antique furniture, bonsai, and a Mark Rothko that he bought as an investment. The new Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce office introduced with season four followed Weiner’s directions that he wanted an open plan, a “rabbit warren” look, to communicate, as Bishop says, that “the control and precision of the 1950s are breaking down.”

There’s a lot being said in the details here, about major and minor characters alike. In the somber season six—laced with death, set in assassination-plagued 1968 and framed with Don’s reading of Dante—Roger’s office is accentuated with a demonic Seymour Chwast poster (“Visit Dante’s Inferno. The End Place.”). When Don gets an older secretary, Ida Blankenship, in season four, the new character comes with a list of items Weiner wanted on her desk, says set decorator Claudette Didul: “Snow globes. A little Eiffel Tower, as if she’d traveled. Some seashells.” Other times, the crew inferred the details from elliptical clues. For Roger’s office, Didul says, “In the first script, [copywriter] Freddie Rumsen comes in and says, ‘It looks like an Italian hospital in here. So we had to figure out: What does an Italian hospital look like?”

Mad Men’s costume department is like heaven’s thrift shop, a cavernous space with racks and rows of madras sport coats, evening wear, cardigans—annotated by episode and season and labeled by character. Every regular cast member has his or her own costume dummy, and as I tour the department a particularly buxom one—let’s call her “Joan”—is modeling delicate red lingerie.

Clothes make the mad man and the mad woman, says the show’s acclaimed costume designer Janie Bryant. She began dressing Pete in blue—so often that the crew began calling a particular shade “Campbell blue”—because “Matt felt that was the sign of a new professional who was very ambitious and a real opportunist.” Joan gets bold “jewel tones,” purple, red, peacock blue, because “those colors are really strong and she’s the feminine force within the office.” And Peggy, as she became a copywriter and executive in the later seasons, appeared in cotton shirts: “It signified that she wanted to be one of the boys.”

For the actors, the very act of putting on the wardrobe, with all the clothes signifying the attitudes and even demands of the times, was part of getting into character. “The biggest physical adjustment was the constraints of the costumes,” says January Jones (for whom Bryant favored “doll-like” pastels that spoke to her desire to maintain perfection). “The undergarments and girdles forced a certain posture and even gait that was uncomfortable at first but also lent an amazing detail to the character. It turned how tied-in and implosive Betty was into a literal fact.”

Maybe the biggest challenge, with a decade’s fabulous fashions to play with, has always been restraint. To research clothing for a new season, Bryant says she’ll go to Sears and JCPenney catalogs as much as she will fashion magazines of the time, to get a sense of how everyday people dressed.

It’s an immersive construction Mad Men’s team have put together, which makes it all the more jarring on set when the director calls “Cut” on a scene and nearly to a person the cast whip out their iPhones. Suddenly, there’s Don Draper in his crisp suit and women in perfectly done-up 1969 bouffants perched on modernist furniture, staring into their glass panels, checking texts and inhaling data in the thoroughly postmodern equivalent of the cigarette break. It’s a bizarre and strangely perfect image: The iPhone, after all, went on the market in 2007, the same year Mad Men went on the air, and it owes much to the clean lines of mid-century design. Even on the set, history repeats.

Then, suddenly, the scene is reset, the iThingies are stashed, the cameras roll again. And you begin to see the writing, direction and performances that turn all of these carefully curated vintage objects into the achievement: you, feeling something.

Part 4

Smoke and Mirrors: The Early Years

Program the time machine: July 19, 2007, the day that “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes,” the first episode of Mad Men, premieres on AMC, and simultaneously March 1960, when we’re first invited into the smoke-filled room that is Don Draper’s life. There are any number of standout scenes in the pilot. Peggy gets a prescription for the Pill from a doctor who warns her not to become “the town pump.” Don flirts with client Rachel Menken while telling her, “What you call love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons.” Joan advises Peggy, on her first day of work, to go home and strip, put a bag over her head, cut some eye holes out, stand in front of a mirror, and “really evaluate where your strengths and weaknesses are.” The reveal, after Don spends a night with his lover, is that he has a wife and kids in the suburbs.

But let’s start with the pitch.

Don has a problem. He’s trying to help client Lucky Strike keep selling cigarettes in the face of a wave of bad press about their product; as a waiter whom he chats up in the opening scene tells him, “Reader’s Digest says it will kill you.” (The warning will echo much later, when Betty is diagnosed with terminal lung cancer in the series next-to-last episode.) Should they find new medical “experts” to swear cigarettes are safe? Appeal to the smoker’s Freudian “death wish”? Don, finally comes up with a different idea: “It’s Toasted.” (This was a rare example of Mad Men using a slogan from real life and a rare anachronism—“It’s Toasted” dates to 1917.) “But everybody else’s tobacco is toasted,” a client protests. “No, everybody else’s tobacco is poisonous,” Don replies. “Lucky Strike’s is toasted.”

It was more than a clever angle. It revealed Don’s approach to life; as he would later remark, “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation.” People loved that scene. AMC loved that scene. “From the second episode,” Weiner recalls, “they were like, ‘Well, who’s the client? Where’s Don’s pitch this episode?’ And I said, ‘I’m not doing that.’ There’s a philosophy in TV that, especially in the first season, you just keep remaking the pilot because you don’t know if people would watch all of the episodes. We don’t do that.”

That decision made a statement about what Mad Men would become. There would be other memorable pitches on the show, but only when the story called for it. Mad Men would not have a formula, and it didn’t rely on shocking twists the way so many series do. Weiner recalls an early episode in which a fellow train commuter recognizes Don as Dick Whitman. His writers pitched the idea of having Don lure the man between cars and throw him off the train. “I said, ‘That would be very exciting,’” he recalls. “‘The audience would definitely come back next week. But Don Draper doesn’t kill people.’”

Instead, the show surprised in subtle ways, by zigging where half a century of TV conditioned you to expect a zag. Pete Campbell looks like the show’s boorish, predatory villain. But we also see his aching loneliness and that he’s one of the most racially progressive people in a very white office. (“Pete always surprised me,” says Vincent Kartheiser. “He was an overly confident, invincible schoolboy that thought he would chew up the world and spit it out. Through the years he becomes more weary, defeated, but wiser and more thoughtful.”) Betty seems like an overgrown child, but proves to have a savvy mind and dark turns of thought. When she realizes Don has paternalistically arranged to have her psychiatrist report to him about her therapy sessions, she uses this to send him the message that she knows about his cheating.

As the show developed, it built a refreshing take on the ’60s. The pilot was, admittedly, a little ham-fisted about how different things were then: the broad nudges that art director Sal (Bryan Batt) is closeted; Joan introducing Peggy to the electric typewriter by reassuring her, “The men who designed it made it simple enough for a woman to use”; Don scolding Pete for stealing a report from his trash, snapping, “It’s not like there’s some magic machine that makes identical copies of things.”

But the show quickly hit a stride, determined not to be the typical Wonder Years story of the ’60s: a story of “turbulence,” “change,” “loss of innocence,” told from the point of view of Baby Boomers for whom Nothing Would Ever Be the Same. Mad Men would be, mostly, the story of people who stand outside change, who fear it and have done fine without it.

This extended to the work at Sterling Cooper. Advertising, in the early ’60s, was in a state of ferment; risk-taking firms were appealing to youth and changing their language from earnest pitchmanship to sophisticated irony. Sterling Cooper was not one of those firms. At one point, Don gets a look at what would be the most celebrated real-life advertising campaign of the time: Volkswagen’s “Think Small,” which would archly jiu-jitsu the critiques of the VW—it was tiny, it was a “lemon”—and turn them into selling points. Don sneers at the ads. “There has to be advertising,” he says, “for people who don’t have a sense of humor.” When we see the counterculture, it’s the ridiculous, pretentious beatniks hanging out with Don’s girlfriend Midge. By the end of the first season, Sterling Cooper is trying to insert itself into the 1960 presidential campaign, developing work for . . . Richard Nixon.

That theme is even more pronounced by the second season. In the premiere, “For Those Who Think Young,” Don is stuck in an elevator with two young men who are telling a filthy story in front of an uncomfortable female passenger. Don, angry, orders one of them to take his hat off. In other words: Show some damn respect. But respect is a dying currency.

Don already hears the footsteps of younger men, who don’t take off their hats indoors, or who, like Pete says of Elvis, don’t wear hats at all. Even the space age is threatening. His colleague and drinking buddy Roger Sterling (John Slattery), a World War II vet, sneers at the hero-worship of Earth-orbiting John Glenn: “I’d like ticker tape for pulling out of my driveway and going around the block three times. It’s not like people were shooting at him.”

Where change comes to Mad Men in those early years, it comes at the margins. It comes, especially, through Peggy. She’s not literally the show’s protagonist—that silhouetted head in the titles is distinctively Don Draper’s—but she’s our surrogate. Closer, generationally, to most of us watching, she enters the world of Sterling Cooper the way we do, as an outsider. The first season establishes her as a wide-eyed newcomer, but soon complicates the picture, then recomplicates it.

At the end of the pilot, for instance, Pete Campbell worms his way into Peggy’s bed, but she’s not the victim. She’s a sexual being too, and while it will never be love for her and Pete, they develop an odd kind of rapport. When Don gives her a chance to try copywriting, she’s good enough to earn a promotion. But she’s not a prodigy; she’s a talented newcomer who experiences the same frustrations and piecemeal triumphs as the men around her. Don takes her as a protégée, and we start to see parallels between them that go beyond their talent with words. Peggy’s surprise pregnancy, ending the first season, cemented the idea of Peggy as a next-generation Don. Visiting her in the hospital, he begs her—not as a boss but as a friend—“Get out of here and move forward. This never happened.” Like him, Peggy gives up giving something up to become who she wants to be. Change comes; but it doesn’t come for free.

Another seismic social change of the period—the civil-rights struggle—happens mostly off-camera, and comes to us mostly through the experience of white characters. Paul Kinsey takes off for a voter-registration drive in Mississippi as much for his own self-discovery as anything. Pete tries to convince client Admiral electronics to take advantage of its television’s popularity among black buyers, and gets scolded for trying to make Admiral into “a ‘colored’ television company.”

Mad Men has always been conscious of the fact that it is a show about privileged white people and of how minorities are, generally, cordoned away from them. The very first scene of the pilot has Don striking up a conversation about cigarettes with a hesitant black waiter at a bar, as a stern white supervisor immediately sweeps in to ask Don if the man is “bothering” him. The black characters in Mad Men are elevator operators, the Drapers’ housekeeper Carla, a Playboy Bunny whom Lane Pryce has a brief affair with. Despite criticisms of the show, the offices are not integrated until the latter seasons—and then, by secretaries. Weiner has remained purposeful about his intentions. “I’ve tried to make a statement about it from the beginning,” he says. “You are seeing segregation. New York is not an integrated place, despite people’s fantasies. And I chose not to lie about the interaction these characters are having with different kinds of people.”

Bigotry comes up in a more blatant way in season three, when Don—the man with a secret—learns that Sal is gay. At first, Don tolerates him, in a way. “Limit your exposure,” he advises. Later he fires Sal when he won’t have sex with an important client who’s sexually harassing him (a decision that contrasts, two seasons later, with Don’s fury at his partners for encouraging Joan to sleep with another client). It’s uncomfortable—as uncomfortable as history often is.

But in those early seasons, Mad Men showed a talent for making a well-trod stretch of history fresh by coming at it, most often, at odd angles. By setting the show at an advertising agency, Weiner was able to focus the passage of time the way most people experience it—through culture, work, the decisions of everyday life, the day-to-day. In “Maidenform,” Kinsey wrangles his way onto a lingerie campaign by coming up with the idea that all women want to be either Jackie Kennedy or Marilyn Monroe. Peggy doubts that, and it’s not the first time that a man overrules her on how women think.

The growth of radicalism on American campuses, for another instance, comes up in season two’s “The Gold Violin,” in which a new young copywriter on staff reads a copy of the Port Huron Statement—the populist manifesto of Students for a Democratic Society—and uses it as inspiration for a coffee jingle. It touches on the reform that will soon come to the Catholic Church with the Vatican II Council, reform personified by Father Gill (Colin Hanks), a guitar-strumming young priest who tries to bring Peggy back into the flock after she’s given away her baby and stopped taking Communion.

In a way, the first three seasons of Mad Men avoided being a clichéd “show about the ’60s” by recognizing that, in culture and style, the era was really still the ’50s, transforming. It’s only really by the third season that we start to get hints of some of the events that will define the decade. The acquisition of Sterling Cooper by a British firm, Putnam, Powell and Lowe, echoes the British Invasion in pop culture. The quietly escalating war in Vietnam intrudes directly (Joan’s new husband, Greg, joins the army after his medical career goes south), and symbolically (an office party turns bloody when a staffer runs over a British executive’s foot with a John Deere riding mower).

Mad Men’s JFK episode—“The Grown-Ups,” the second-to-last of season three—is not one of the show’s best. It’s nigh impossible to depict the assassination realistically without the moments that have been re-created so often they’ve lost their power: the TVs tuned to network news special reports, the Jack Ruby shooting of Oswald and so on. But what makes Mad Men’s approach to the assassination quintessentially a Mad Men approach is how the episode focuses—painfully, awkwardly, brutally—on how life has to go on. So Roger grits his teeth and holds his daughter’s wedding, knowing full well how terrible it looks. PPL continues its gutting of Sterling Cooper, setting off the Ocean’s 11–style coup that will send Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce off on its own (in the season finale, “Shut the Door. Have a Seat,” which is one of the show’s best-ever episodes). And after it had seemed that Don and Betty would weather her discovery of his identity—one Big Lie too many after a marriage full of them—the Kennedy catastrophe seems to push her to make a decision.

Once more Mad Men becomes a show that does things TV series are not supposed to do—namely, have the central couple get divorced three years into the show’s run. As with the Cuban Missile Crisis at the end of season two, this calamity is not a deus ex machina that suddenly causes people to change their lives. Rather, it just causes them to live their lives, as they might have anyway, but more intensely, maybe with a greater—if temporary—clarity of purpose. And here, in November 1963, the historical becomes achingly political, as Don talks to his kids about the assassination in the same terms: We’ll be sad for a while, but then we’ll be okay. The words one uses when describing, well, a divorce.

The Drapers’ marriage is over. The business has relaunched itself. JFK is dead. And the ’60s—the popular idea of the era as opposed to the calendar date—have begun.

Part 5

“That’s What the Money Is For!”: Don and Peggy Unpack Their Baggage

I’m going to pull the lever and stop the time machine on May 25, 1965, the date of the second Cassius Clay–Sonny Liston title fight, and the date of “The Suitcase,” Mad Men’s best hour to date.

Weiner designed Mad Men symmetrically. Its first three seasons covered the pre-’60s, essentially: a time of reserve, muted tones and New Frontier optimism, when the world was run by men who wore hats. Its last three spanned the late ’60s, all disorientation and colorful entropy, as the culture became more baroque, the hemlines rose, the hats came off and the rules flew out the window.

Mad Men also built a symmetry between its two major characters, Don and Peggy. Like a mirror reflection, she is both the same as him and his opposite. They’re both creative. They can both be difficult. They have, to some extent, cut ties with their past to try to make a future. But she’s a woman and he’s a man. She’s young and he’s older. She’s ascendant, while Mad Men is largely the story of his fall (as the opening titles unsubtly suggest).

Mad Men’s season four falls roughly in the middle of the ’60s: from late 1964 to late 1965. Also, as we now know: smack in the middle of Mad Men’s run. In the middle of that season, its seventh episode of 13, comes “The Suitcase,” the fulcrum of the series, which brings these two ships together over one stormy, drunken working night.

In some ways, in season four, things have never been better for Don. He has ended what was not exactly the world’s healthiest marriage. He’s started a new business. Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce has set up shop in the Time & Life Building, a gleaming glass tower, barely five years old at the time, whose open spaces, custom-designed Eames chairs and clean lines suggested a gleaming future.

That’s the façade. (It would come apart, literally, as the agency was swallowed by McCann-Erickson and the office gutted in the second half of season 7.) The reality in Mad Men is unpretty. Don is a rudderless, morose drunk, living in a Manhattan bachelor pad. He sleeps with his secretary, then gives her $100 in a Christmas card. His oldest friend—Anna Draper, the real Don’s free-spirit wife who helped Dick Whitman pull off his identity change—is dying of cancer in California. SCDP, meanwhile, is one big client away from disaster (and ends up losing that client, Lucky Strike). The firm pretends to have a second floor that does not actually exist. “The outside looks great, the inside is rotten,” as Jon Hamm puts it. “That’s America in the ’60s.” Don is free to be himself now. But he has no real idea who that is.

Peggy, on the other hand, is moving up, finding herself as a woman and as a professional. Early in season two, Bobbie Barrett, a woman of an earlier time, advises Peggy that since she can’t be a man in the business world, “be a woman. Powerful business when done correctly.” But as Elisabeth Moss puts it, “Peggy’s story, the story of feminism at the time, is figuring out that it’s not about being a man or a woman—it’s about being yourself.”

On a show that is exquisitely melancholy, watching Peggy become herself offers a welcome change. She’s gone from dressing like a timid Catholic schoolgirl to looking like a confident professional. She can put together a lyrical ad pitch to rival Don’s best, as when she casts the Popsicle as a secular Eucharist: “You take it, break it, share it, and love it. This act of sharing; it’s what a Popsicle is.” (“Why don’t you just put on Draper’s pants?” grouses a dejected male colleague.) And while we’re talking religiosity: She embraces a particularly ’60s sacrament when she crashes a smoke-filled office meeting and delivers an all-time classic line: “I’m Peggy Olson. And I want to smoke some marijuana.”

As “The Suitcase” begins, it’s Peggy’s birthday, a reminder that, for single women in 1965, society still treats the calendar like a scoreboard. In the SCDP ladies’ room, she runs into Pete’s pregnant wife, Trudy, who condescendingly tells her, “You know, 26 is still very young.” Peggy has dinner plans with Mark—her boyfriend, whom she’s ambivalent about—and her family. But Don keeps her late to hash out ideas for a problematic client, Samsonite luggage. No one else is around. The executives, and seemingly the rest of the world, are going to see what’s happening with Clay-Liston.

Samsonite is a problem, but not as big as the one Don is working late to avoid. He has a phone message from California, which can only be bad news about Anna. He has been drinking all day; his face is as red as a tomato. They kick around ideas. Maybe an elephant could sit on the suitcase? An airplane could run over it? Don suggests, though, “a bag under an airplane looks like there’s been an accident.”

Peggy’s angry about staying late. She is on some level relieved, maybe, to miss an uncomfortable dinner, but she’s angrier that Don doesn’t think twice about asking her to stay. Peggy has resented Don all season for winning a Clio award for a floor wax commercial that she provided the initial idea for.

“It’s your job,” he snaps. “I give you money, you give me ideas!”

“And you never say, thank you.”

“That’s what the money is for!”

What follows is a strange, compelling night. Don calls Peggy into his office, to listen to a recording he’s just found of Roger dictating notes for his autobiography. They go to a Greek diner, then to a bar, where they hear Clay knock out Liston over the radio. Don asks Peggy if she ever thinks about the baby she gave up. They talk about the miniscule difference between a great idea and a terrible one. They learn that they each saw their fathers die before their eyes. Back at the office, Don throws up noisily and finally breaks down in front of Peggy. It’s like seeing Superman unmasked as an alcoholic, vomit-stained Clark Kent.

When Peggy wakes up on her couch the next morning, that broken man is gone. Groggy and disheveled, she finds Don, composed, washed, his shirt clean. He’s Superman again, but it’s not so much a sign of strength as of how expert he is at hiding his disease. But he has an idea: a sketch of a Samsonite suitcase looming over a competitor in a boxing ring, echoing the Clay-Liston photograph in the morning’s papers. She tells him it’s a good idea. This time she means it.

Anchored by stunning, vulnerable performances from Hamm and Moss, “The Suitcase” is the perfect distillation of Mad Men. It’s about two characters with a complex relationship. It’s about how change creates opportunity for some and threatens others. (Don, revealingly, hates the “bigmouth” Clay, preferring the older, experienced, more stoic Liston.) And it’s about the creative process, about where ideas come from: from some combination of insomnia, whiskey, self-doubt, pain, competition, junk food, anger, laughter, love—and the mystical. Early in the night, in one of those brief, surreal cutaways Mad Men loves, Don sees a mouse scamper across the floor of his office. Later, he and Peggy see it again, but though Don wants to find and catch it, it scampers under his couch and seems to disappear. “There’s a way out of this room we don’t know about,” Don says.

Come morning, Don and Peggy—like every other character on Mad Men—are still looking for a way out of their own personal mazes. But through this long, draining night, they’ve found the magical hole to escape one, small problem. It’s another day, and they have their pitch. It’s a start.

Part 6

Making History: The Later Years

After season four, Mad Men collected its fourth consecutive Emmy for Best Drama (no basic-cable show had ever won the award even once), adding that to several Emmys for writing and technical categories. (Absurdly, the show has never won an acting Emmy.) AMC’s plan had worked; the show put it on the TV map, allowing it to launch other critical favorites like Breaking Bad and the commercial blockbuster The Walking Dead. You might have excused everyone involved for coasting on its success.

But there would be no coasting, creatively or business-wise. After season four, contract negotiations turned tough. A critical favorite, Mad Men was the new synonym for high-quality TV. But it was expensive to produce, so the network asked for cuts in the cast and budget as well as a shorter running time for episodes in order to make room for more ads. Discussions continued. At one point during negotiations, Weiner later said, he actually briefly quit the show.

In the end, Weiner got most of what he wanted: no mandated cast reductions and only small snips to the length of some episodes. In addition, Weiner announced that the series would set an endpoint: seven seasons and done. “I asked them, how much more do you guys want of this?” he says, which allowed him to start thinking about how to end the story.

It was 17 months before the show returned in 2012. When season five did premiere, it was a different, more experimental, rejuvenated show. Like Don, who had proposed to his secretary Megan at the end of season four, it was a bit like a man on his second marriage—cleaning out his closet, moving into a new pad, trying out a new look at midlife.

Part of the shift reflected how the tone of the ’60s itself was changing (it’s 1966 when the season begins). The colors are more vivid, the fashion more aggressive and swinging. The culture is coming out of its shell and flashing plumage, becoming more psychedelic and youth-oriented. Where SCDP’s clients used to resist change, they now want, as one puts it, “the chaos and the fun—that sort of adolescent joy.”

The season premiere, “A Little Kiss,” captures the feeling in a breathtaking set piece. Quebecois actress Megan, at a party for SCDP colleagues at her and Don’s apartment, serenades him with the French ye-ye pop song “Zou Bisou Bisou,” slithering, posing, tossing her hair and running her fingers down the front of her black miniskirt. It’s sexy and a little inappropriate; the guests, men and women alike, look jealous and aroused. She’s amazing, and Don is mortified. All in one sequence, it sounds a theme of the later years of Mad Men: the seductive, terrifying power of youth and change.

There’s a playfulness and recklessness to the story structure in the later seasons; more than ever, the episodes begin in the middle of stories and trust the audience to catch up. Beginning a story at odd ends—say, with a car crash in a drivers’-ed video at the opening of “Signal 30”—creates the sense that you never know where a particular episode is going to go.

The unpredictable structure echoes the unpredictability, the sense of chaos, in American life in the era. The news fills with war and mass murders like the one committed in Chicago in 1966 by Richard Speck (a subplot in “Mystery Date”); there’s a sense of things falling apart. That chaos is reflected in season five’s most ambitious episode, “Far Away Places,” which skips among three stories, including Roger’s first trip on LSD. Instead of using the usual kaleidoscopic colors and trippy music, it’s shot naturalistically and hyper-lucidly, made disorienting by editing cuts (as when Roger observes himself from across a room) and auditory hallucinations (Roger sits in a bathtub and hears the noises of the 1919 World Series). “If you had said in the first episode that Roger would be the first one to try acid,” quips John Slattery, “no one would have believed you.” Yet with the hedonistic, spiritually adrift Roger, it somehow makes perfect sense.

Even as the colors get brighter and more saturated, the themes get darker. SCDP is thriving, but at a cost. Lane Pryce engineers a coup to win Jaguar as a client for the firm, but he does not pull this off before he’s overcome by crippling debts and hangs himself in his office. To secure that Jaguar deal, Joan ends up accepting a deal to sleep with a vile dealership owner, in exchange for a partnership stake in the firm. Throughout, there’s the presence of seamy doings and even horror behind images of luxury and success, as when Don’s daughter, Sally, enjoying an elegant night at an awards banquet, opens a door to see Megan’s mother fellating Roger Sterling.

That leitmotif of secret decay comes back, of course, to Don. He’s rich, he’s newly married (and even, for a while, faithful), and he’s as handsome as ever. But he’s also losing a step. At home, he’s seemingly happily married, but not sure how to be with a younger wife who has ambitions and a life separate from his. At work, his pitches are off, his feel for the culture shaky. He may have plateaued, or worse. In “Lady Lazarus,” an elevator door opens for him and he finds himself staring down an empty shaft. Later in the same episode—in which Don complains about not understanding his clients’ musical references—Megan gives him the Beatles’ Revolver album. He puts on “Tomorrow Never Knows,” with its distorted vocals, sitar and backward guitar, and sits, sipping his Scotch, somberly, like a man listening to his own eulogy. Then he pulls the needle off the record.

It’s a telling musical choice, certainly. As with its design and fashion, Mad Men usually preferred to make obscure, well-curated musical selections. The Beatles, on the other hand, are as classically, iconically, capital-S Sixties as it gets. (Yet their songs are almost never used on TV; getting the rights required lengthy negotiations and around $250,000.) But “Tomorrow” is a deep cut: literally the album’s last track, artistic, inaccessible, not a greatest-hits staple.

That’s how Mad Men had to approach history as it got later into the 1960s, deeper into events that we remember and that people living at the time couldn’t ignore. It had to find a way to be both obvious and fresh. This became even more true in season 6, set almost entirely in 1968—a year wherein the popular concept of “the ’60s” essentially boiled down to 12 loud and brutal months. The MLK assassination, the RFK assassination. The Tet Offensive and the My Lai massacre. The Paris riots and the Democratic National Convention bloodshed. Eventually, Richard Nixon’s election.

Sometimes, season six treated these events obliquely: We hear about Martin Luther King’s assassination while watching Paul Newman, a blur in the distance, speak from a podium at an advertising awards banquet where Don and company are in the cheap seats. Weiner says that ultimately the show had to embrace the notion of 1968 as a time of general turbulence, because the specific clichés happened to be true. “I cannot pretend like this is not going to have an effect on people’s lives,” he says. “The first time you have your first hippie, you’re just like ‘Am I doing Dragnet here?’ But when you go to the archival footage—you can’t re-create that without looking like a cliché, because it really looked like that.”

What the show did was to refract history through the lens of ordinary life, the way people experience it. When King dies, the shock reverberates through that episode in idiosyncratic ways. Don escapes to the movies with the King killing. He goes to see Planet of the Apes—which was released just before the assassination and was often read as an allegory of racial prejudice. Peggy, meanwhile, is looking for an apartment, and the fear of riots in Harlem leads her real estate agent to suggest she put in a lowball offer on a place in a safer neighborhood uptown. In the season premiere, Don, on vacation in Hawaii, meets a soldier off to Vietnam and mistakenly ends up with his cigarette lighter. It reverberates with world history (the “Zippo squads” who torched villages during the war) but also Don’s—the original Don Draper who died, allowing Dick Whitman to take his identity, when he dropped his lighter in gasoline in Korea.

That notion of history repeating is where Mad Men departs from the usual take on 1968. The prevailing wisdom is that it was a year when “everything changed.” There were a lot of dramatic events, Weiner argues, but the real refrain was the dashing of the hopes for change. “It starts with so much hope and underdog spirit and so much virtue,” he says. “And every one of these things is thwarted or crushed or killed internally. Martin Luther King is killed and that’s shameful, but it could be the thing that galvanizes a movement. Then Bobby Kennedy is killed. And then you see the Russians roll into Prague, the massacre in Mexico City, the French students being batted down, finally the Democratic convention, where on U.S. soil we see a protest that looks like it’s happening in the Third World. And then what happens at the end? Richard Nixon is President. ‘Please, bring some order back into this.’”

Nixon, of course, is Sterling Cooper’s man from Mad Men season one. But that’s not the only pattern repeating amid change. To save itself, SCDP merges with rival Cutler Gleason and Chaough and becomes SC&P, recalling the corporate derring-do in season three. Don, meanwhile, is drinking heavily, failing his rudderless daughter, Sally, falling into a destructive, guilt-ridden affair with Sylvia (Linda Cardellini), the wife of a neighbor. Some fans and critics complained that Mad Men was beginning to repeat itself, covering old ground, but Weiner says that was the point, thematically and chronologically. “We repeat things in life all the time,” Weiner says. “It’s a psychological principle called ‘repeat to master.’”

Until Don breaks the pattern, and sets in motion the end of his story.

Part 7

The End of an Era: Mad Men’s Last Act

“Television, series television, is based on a lack of resolution,” Weiner says. “Even on procedurals where the case is wrapped up, Sherlock Holmes will be back next week. Nobody grows, nobody changes.”

That’s what seemed to be happening with Don toward the end of season six, which even built toward a classic Mad Men resolution: Don needs to salvage a crucial deal with Hershey’s Chocolate by coming up with an 11th-hour emotional pitch. It doesn’t happen. Don makes up a happy memory for the candy men about his father giving him a chocolate bar as a reward for mowing the lawn. It’s lyrical and sounds heartfelt; he has the executives wistfully riding the carousel just like the clients from Kodak at the end of season one. But in that moment, something snaps, and he tells them the truth: that he grew up an orphan in a whorehouse, eating Hershey bars as a lonely reward for helping the hookers fleece their johns. The clients are mortified. Don’s partners are furious, and they put him on leave.

What Don has always feared has come to pass—he has exposed his true self and he might be ruined for it. Yet there’s a hopeful note here. Don has lost his job. He may be losing his wife, as he gives Megan his blessing for her to move to L.A. without him and pursue her acting career. But the season ends with him taking his children—who yet know nothing of his past—to see the rundown house in Pennsylvania in which he grew up. There’s a black boy on the stoop now, eating a Popsicle (Peggy’s symbol of communion from season 2, but this time a lonely one) a small but telling detail about the underclass in the ’60s and, earlier, the ’30s.

Mad Men’s last acts were shaped by one more behind-the-scenes deal with AMC. Another of the network’s successes, Breaking Bad, had broken its final season into two parts, the last of which ended up being a ratings smash as its momentum built. The network saw an opportunity to extend Mad Men’s run, and Emmy eligibility, by giving the last season an extra hour and splitting it in half. (Fittingly enough, the device was like a whiskey cocktail: seven and seven.)

Weiner wanted to construct the final season as two mini-seasons. The first centered on a different Don than we were used to: humbled, out of power, trying to earn his place back at SC&P by buckling down, checking his ego, writing tags and coupons, and being a team player.

He wasn’t taken back easily. Joan, for instance, still angry that Don scuttled the firm’s public offering after she’d had sex with sleazy Herb from Jaguar to make it possible, voted in favor of a motion to boot him from SC&P. This upset some fans, but it was another example of how Mad Men chooses messy realism over what TV has taught us to expect. “Just because you work together,” as Weiner puts it, “doesn’t make you best friends.” By season’s end, Don had come back—sort of—after Roger engineered a deal to have SC&P bought out by (real-life) advertising giant McCann-Erickson.

The seven episodes elevated what had been a quasi-character for Mad Men’s whole run: the state of California. It’s where Don went to re-create his identity after Korea; it’s where he found a second (okay, technically third) wife, proposing to Megan after a trip to Disneyland in the perfectly named “Tomorrowland.” It’s lingered out there—a horizon, a possible future, an escape hatch, a place to erase your past and construct a new identity out of stucco.

California symbolized the end of the East Coast-dominated hierarchies in which Don and his peers have found such success. It’s also, in a way, a harbinger of the end of Mad Men, in that California is, culturally, where the ’70s would come from. It’s rising as New York City is falling into decay. “It has everything that New York’s missing,” Weiner says. “The frontier aspect, the hot rods. Internationally, the focus on the United States was going from New York to San Francisco and Los Angeles. Richard Nixon was from California. Ronald Reagan was from California.”

Now, in season 7.1’s 1969, that future is arriving. Pete Campbell and Ted Chaough have opened a satellite office in Beverly Hills. Pete, the recently separated East Coast blueblood, is transformed, with a new girlfriend and killer sideburns. (“The city’s flat and ugly and the air is brown,” he tells a visiting Don. “I love the vibrations!”) Megan, meanwhile, is thriving there, with a network TV pilot and a bungalow in the hills—near the same hills where another actress, Sharon Tate, would die in the Manson Family murders later in 1969. (The parallels were so strong—Megan even wearing a T-shirt identical to one worn by Tate—that Weiner, uncharacteristically, commented on future storylines by assuring people that Megan was not about to be slaughtered.) When Don visits Megan, they’re out of sync. He surprises her with a TV set, but it’s too big for her tiny house. And it becomes clear there’s not really room for him either.

But the episodes were about more than Don. We saw Peggy come into a new confidence out of Don’s shadow; the finest hour of the half-season, “The Strategy,” recalled their all-nighter from “The Suitcase” as they worked on the Burger Chef account, but this time Peggy takes the lead. Initially, Pete argues that Don, the man, would be better off making the pitch: “Don will give authority. You will give emotion.” “I have authority,” she answers. “And Don has emotion.”

Rather than steal the coup from Peggy, Don works with her—as a colleague, not a boss—and she realizes that she has the ability and ideas to run the show, not as Don in a skirt but as herself. “That pitch was one of the harder things we had to write,” Weiner says. “We wanted to make sure it sounded like Peggy and not just like a rip off of Don, because a lot of what she had done was a derivation of his style.”

Season 7.1 ended with the end of the ‘60s in sight, with Bert Cooper dying after watching man land on the moon in July 1969. So how did season 7.2 return? By blowing past the endpoint the entire run of the show had led us to expect and returning in spring 1970. We skipped New Year’s Eve, we skipped Woodstock. (“The average person didn’t go to Woodstock,” Weiner says. “They saw the documentary a year later.”) It was, in retrospect, the most Mad Men thing Mad Men could do, to have an apparent focal point of the show’s run happen off-screen, as if to say: Stop watching the clock, the calendar’s not the point here, the people are.

But while the return anchors the series in time, Don is feeling unmoored. Early in the season premiere, he has a dream of Rachel Mencken—“You missed your flight”–who turns out to have just died. When he tells brooding waitress Diana, his new love interest, about the dream, she asks him to think hard about when he really had it: “When people die, everything gets mixed up.” Stripped of his firm, his marriage, his apartment, Don is living in 1970, but he’s also still living in his past.

The past and regret are big themes of the final run of episodes. When Ken Cosgrove is fired by the new bosses at McCann, he takes it as a sign of “The life not lived.” Peggy also misses a flight, as she ends up not taking an impulsive trip to Paris with a new lover, and it’s another plane—seen out the window as Don finds himself in a tedious meeting at the overstaffed McCann—that prompts him to jump into his car and make one more Dick Whitman break for it, out West.

There’s a different sort of business drama playing out in the half-season, with the SC&P refugees struggling not to stay in business but to maintain an identity as they’re absorbed into a corporate behemoth where they simply don’t matter much. When Joan complains of sexual harassment, she’s treated like an annoyance; to McCann’s Jim Hobart, she’s simply one of the office supplies that came with the trophy acquisition of Don Draper, and he feels generous allowing her to leave with half her money. Peggy isn’t even assigned an office at first; when she finally walks in, dark shades, cigarette dangling from her lips, we don’t know if she’s marching to victory or a firing squad.

There’s a feeling of extended leave-taking in these last episodes. We see the SC&P offices being dismantled like a stage set (Roger and Peggy hold a lovely, tiny impromptu wake, he playing an organ in the darkened offices, she roller skating through the empty halls). It’s most poignant in the penultimate episode, when Betty is diagnosed with terminal cancer; the bill has come due for all those years of selling tobacco, yet somehow it’s not Don who gets the check.

It’s devastating, but not saccharine: Betty remains Betty even facing death, practical, defiant, leaving Sally a set of instructions for the funeral arrangements before telling her “Your life will be an adventure.” For Mad Men, neither death nor the end of the series exempt it from living the truth of its characters, for good and bad. It’s Pete’s ex- (and future?) wife Trudy, of all people, who voices the show’s philosophy about that: “You know, I’m jealous of your ability to be sentimental about the past. I’m unable to do that. I remember things as they were.” (In a further, typical complication, of course, she ends up sentimentally taking Pete back.)

Likewise, when you talk to Weiner about the end of the series, about what he wants to say with the finale, what you get is not simply nostalgia—not sentimentality or any notion of working toward a final endpoint in time. While working on the last episodes, Weiner’s been thinking about history and time on a broader scale than the 1960s or even the 20th century. He’s been thinking, for one thing, about the French Revolution.

“I’m not comparing myself to him,” Weiner says, “but Charles Dickens wrote A Tale of Two Cities about 50 years after the French Revolution. Was he just interested in the French Revolution? No. He’s writing the novel in London, at a time of a lot of change, industrial revolution and poverty and—you know, Dickensian means one thing. The end of that book is a man sacrificing himself. ‘It’s a far, far better thing . . .’

“But if you read the rest of that ending, which is one of the greatest payoffs in the history of entertainment, he talks about the Place de la Concorde, where the guillotine stands, that one day, there will be flowers growing there. All this will pass. This is a time when the streets are running with blood, and then there will be a time when there are flowers growing here, and everyone will forget it. But it will still be the same place.”

It will still be the same place. That, finally, is what Mad Men is showing us. When we visit its time, there may be more cigarette smoke and whiskey, but it’s not an alien planet. We’re visiting our own time, just with a few layers of wallpaper scraped off the bedroom wall. We’re visiting the same place we live, even if you’ve never set foot in midtown Manhattan.

Mad Men isn’t a “period piece,” not in the classic sense that it tries to re-create another time and tell us how it was all different then. It’s about a kind of holy idea: that one moment contains all other moments. That if you study one time and one group of people well and deeply enough, you understand all times and all people.

It’s an idea the show has in common with spirituality, and, strangely enough, also with science fiction: that four-dimensional, unstuck-in-time concept of one moment connecting with every other. Early in the show’s run, Weiner described the show as “science fiction set in the past”—and what is the favorite subject of science fiction if not time?

Indeed, when you go back and watch Mad Men, you find a lot of sci-fi woven into it: Ken Cosgrove’s short fiction, Paul Kinsey spec script for Star Trek, young Sally playing “spaceman” with the dry-cleaning bag. As Don drives west at the end of “Lost Horizon,” it’s to the disorienting strains of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity.” And when Don’s elderly secretary Ida Blankenship dies at her desk in season four, Bert Cooper eulogizes her with a surprising image. “She was born in 1898 in a barn,” he says. “She died on the 37th floor of a skyscraper. She’s an astronaut.”

So are we all if we are lucky enough to live, traveling into science-fiction worlds one day at a time. Watching Mad Men, we’re like Charlton Heston’s astronaut from the climactic Planet of the Apes scene we saw Don watch with his son. We’re exploring an alien landscape, becoming absorbed in it, being fascinated and sometimes horrified by its differences—only to realize, in the end, that that’s our Statue of Liberty buried in the sand. It was our world all along.

There’s one difference, though. Charlton Heston came back to earth by spaceship. But this device, as Don Draper said of the Carousel so many years ago, is not a spaceship. It’s a time machine.