Lindsey Rogers-Seitz fits the description of a typical corporate lawyer. She speaks convincingly about the intricacies of the law. For years, she worked long hours in Manhattan, commuting home to Ridgefield, Connecticut. She is calm yet authoritative. You get the feeling she’d be ready to present to a boardroom at a moment’s notice.

But these days she isn’t spending her time juggling cases. Instead, she’s logging hours researching heat-stroke deaths in cars. She wants to know how it is that people, especially children, die of heatstroke in hot cars, why it happens, and the measures—regulatory, technological and otherwise—that can be implemented to prevent them. The mission is a personal one.

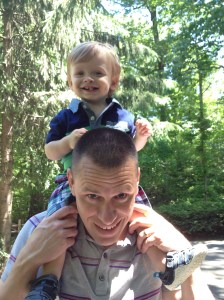

Rogers-Seitz’s 15-month-old son Ben died in July after her husband Kyle accidentally left the child in the backseat of their family car for hours, she says. There was a break from routine, and Kyle never dropped off Ben at daycare as he had planned. Instead, Kyle went to work, and at the end of his workday, he drove to the daycare to pick up Ben. That’s when he realized the child had been in the back seat all day.

The temperature outside lingered in the 80s that day, but inside of the car, it was much hotter, perhaps above 110 degrees—hot enough to kill a baby stuck in a car for hours. On Aug. 21, the Connecticut medical examiner ruled the death a homicide by hyperthermia. The judgment means that Kyle is responsible for the death, but experts say he is unlikely to face murder charges and may not be charged at all.

There is no one way to grieve, but Rogers-Seitz has taken an advocate’s approach. She doesn’t blame her husband. Instead, she wants to know how something like this could happen in the first place. “I guess being a lawyer, the way that I look at things is a little different,” she says. “I’m looking at things from a lawyer’s point of view and a mom’s point of view.”

That means she went digging.

In the United States in 2013, 44 children died of heat stroke in cars, and more than 600 have died since 1998. The fact that heat gets trapped in cars is no secret to anyone who has parked in the sun and returned to a seatbelt buckle too hot to touch. But considering the dozens of young children who die of heat stroke in cars each year—and the fact that developers have been working on technology to prevent these deaths since the late 1990s—many question remain about why advanced sensors or other technology aren’t already in use by car manufacturers.

More than 600 children have died of heat stroke in cars since 1998.

In her search for answers, Rogers-Seitz began poking through government documents, and before long, she stumbled upon a fierce debate among advocacy groups, government agencies and auto manufacturers.

Safety advocates push for investments in technology that seek to counteract the mistake that leads a parent to forget his kid in a hot car—an error, they say, that, tough as it can be to imagine, can happen to anyone.

But many car companies and researchers say existing technology isn’t reliable enough to prevent death. Instead, efforts should be focused on public awareness, they say.

Technology is not a cure-all and neither is public awareness. Anyone who’s serious about stopping hot-car deaths needs to consider investing time and energy into technology. But child safety advocates say the urgency isn’t there among manufacturers. For the auto industry, some say, the financial costs and the risk of liability may provide a clear reason to leave technology alone. And for parents, no amount of public awareness is likely to stop the sort of forgetting that neuroscientists and psychologists say is a normal part of busy lives.

Technology’s Trials

There’s a terrible irony at the center of heat-stroke car deaths: as cars have grown safer, a parent’s risk of leaving his or her child there has increased.

Throughout nearly all of the automobile’s first century, adults traveling alone with their kids had little reason to put them in the back seat. But a 1991 federal law encouraging manufacturers to install air bags changed that. By 1998, airbags were saving more than a thousand lives per year, but, at the same time, they killed dozens of small children who were sat in the front seat and could not withstand the force of the device. In 1998, 32 children died from an airbag. Safety advocates began to tell parents to move their kids to the back.

It’s good advice, but data cited by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) suggests the recommendation made parents much more likely to forget a child. Five children died in overheated cars in 1990. That number grew in the 1990s along with the prevalence of airbags: 35 kids died in 2000.

Aware of the troubling rise in hot-car deaths, developers and inventors, many of whom had no connection with the auto industry, set to work on technological solutions like heartbeat sensors and seat belt alarm systems. Inventors filed these patents as early as the late 1990s.

In 2001, General Motors announced the carmaker had developed a radar sensor that would detect children in cars. That same year Volvo developed a heartbeat-sensing device. Researchers hoped it would detect children in the back seats of cars, but they found the device unreliable at weights under about 65 pounds. (They adapted it for burglary prevention instead.)

“It was a wish that the type of sensor could cover much more, but there were some limitations in the technology,” says Jan Ivarsson, manager at the Volvo Cars Safety Center. “As we introduce things on the market, it must be things that hold the promise to the owner of the car.”

In other words, the technology wasn’t as reliable as car manufacturers wanted it to be in order to ensure the safety of the people aboard.

Technology in cars has evolved dramatically in the past 13 years. There are remote-control rearview mirrors. Power doors open at the touch of the button. Cars can park themselves. Gadgets tell you how to get from one place to another all while avoiding traffic. And in that time, the equipment that could protect children from heat-stroke deaths has evolved too.

A lot of it is already on the market and can be adapted for small children, according to Sudeep Basu, an automobile industry analyst at Frost and Sullivan, a consulting and research firm. Today, cars sense weight in a seat. You’ve probably encountered that technology by the noisy beeping sound your car makes when you forgot to put on your seat belt.

“The individual competence already exists. It’s about bringing it together in the system,” Basu says. “It’s not a question of being technologically possible. It is.”

“It’s probably a safe assumption that this is something that automakers are looking at,” says Wade Newton, a spokesperson for auto manufacturing trade group Auto Alliance.

“It’s not a question of being technologically possible. It is.”

Indeed, a Toyota spokesperson said the company was working on technology to stem heat stroke deaths, though she didn’t provide details. A representative for Volvo also said that the company was working on similar technology.

But if the car companies acknowledge that they’ve been developing the technology, why hasn’t the public seen it yet?

“You Can Prevent These Deaths”

In the debate over hot car deaths, the line dividing the parties has been drawn clearly. Car manufacturers say the technology hasn’t developed to a point where it would serve its purpose effectively. They’re joined by Safe Kids Worldwide, a public safety group funded in part by the General Motors Foundation. Together they sponsor public awareness efforts aimed at reminding parents not to leave their kids in the car.

Awareness helps, but evidence suggests that it will make no difference in saving the lion’s share of children who die of heat stroke in hot cars. Psychologists and brain scientists say that accidentally leaving your child in a car is an easy and honest mistake. A distraction or irregularity in a parent’s daily routine leads him to forget his child or to think the child has already been dropped him at daycare or with a caretaker.

“There’s so much in common with forgetting other things,” says David Diamond, a neuroscience professor at the University of South Florida. In many cases, parents forget their children because they’re accustomed to the other parent dropping them off or because they’re taking children to a place the parents don’t usually go.

“I don’t think that there’s any automaker that feels they have technology that’s reliable enough,” says Wade Newton, a spokesperson for auto manufacturing trade group Auto Alliance. “I don’t think an automaker has been able to perfect it yet.”

A 2012 report from NHTSA and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia concluded that existing after-market solutions—products offered by independent developers that could be installed by the owner of the car—were insufficient.

“Although the designs were generally fundamentally sound, they were not as reliable as one would like,” says Aditya Belwadi, one of the lead researchers on the study and a biomedical engineer who studies the causes of injuries. “These are circumstances where they have to work all the time.” Belwadi and his co-researcher Kristy Arbogast describe the report as “a snapshot in time.” It evaluated three products sold in 2012—not technology being developed today by automakers. The likes of Kids and Cars and Lindsey Rogers-Seitz are quick to point out that distinction.

For the automakers, concern about liability and the cost of implementation are real, says Janette Fennell, president of child safety group Kids and Cars. Manufacturers are also concerned that if their product malfunctions or parents use it incorrectly, they may face expensive lawsuits.

While automakers declined to answer questions about liability concerns on the record, their worry over lawsuits surrounding new technology is obvious. Autmomakers frequently face liability suits that cost millions, sometimes billions, of dollars.

“You can prevent these deaths,” says Joan Claybrook, a former NHTSA head. “People are human and have failures of memory and to the extent car technologies can help them…those are just fabulous, and they’re not that expensive.”

Government regulators are focused on spreading awareness so that parents are aware of the risks, but they draw their strength through the laws passed in Washington. That’s the next frontier for people like Fennell. Claybrook says the prospect for real federal intervention worries auto manufacturers. If car companies successfully create a product, legislators might eventually mandate it.

The situation is similar to the development of rearview cameras at the back of cars, Claybrook says. Manufacturers offered it as an add-on. It worked, and now a federal law requires that all new cars include it by 2018. Numerous car companies opposed the legislation.

A Mother’s Mission

Back in Ridgefield, Conn., with her two daughters, aged 5 and 8, away from the house on a recent day, Lindsey Rogers-Seitz takes in a quiet moment on her back porch. Kyle, her husband, is inside. He declined to speak to TIME as his legal case remained unresolved. In Connecticut, endangering the life of a child by leaving him or her in the car is punishable by up to a year in prison.

The family has the support of their community and family, Rogers-Seitz says. She knows she needs to work to put her life back together, but she’s doing it in her own way. She’s been in touch with members of Congress and has drafted a piece of legislation. She calls it “Benjamin’s Bill,” and it focuses on what she calls the “think-tank approach.” Methods for reducing children’s heat-stroke deaths in cars would be studied before long-term initiatives are implemented.

Rogers-Seitz says she knows the legislation would be difficult to pass, and, even then, its most stringent provisions would only kick in 18 months after enactment. There will be heat stroke deaths next year, and the year after, she says. But that’s not stopping her.

“I had a decision that night in the ER. I was either going to break down in hysterics and not function or I was going to move on with my family united and try to do something positive. And that’s what I did,” she says.

“Ben was my heart, and Ben will always be. I can find the happiness I had through his smile by helping other people. And trying to save their kids’ lives.”