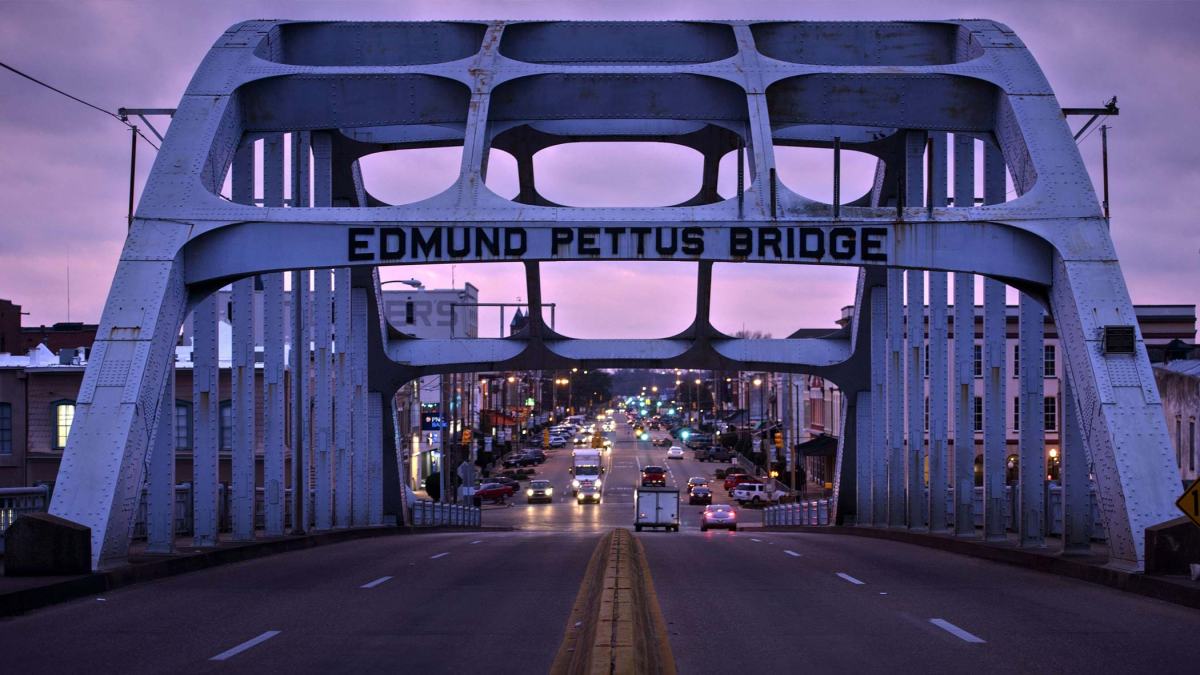

ada Flanagan crosses the bridge every year. The 16-year-old wasn’t alive when Alabama State troopers attacked peaceful marchers on the way to Montgomery, Ala., but she recognizes the importance of the structure that acts both physically and symbolically as the entryway to Selma, Ala.

ada Flanagan crosses the bridge every year. The 16-year-old wasn’t alive when Alabama State troopers attacked peaceful marchers on the way to Montgomery, Ala., but she recognizes the importance of the structure that acts both physically and symbolically as the entryway to Selma, Ala.

“I make sure I march,” says Flanagan, whose mother participated in Civil Rights protests as a 6-year-old in Selma. “They fought hard for their rights so that us as a generation could have our rights.”

Flanagan plans to be among the thousands crossing the Edmund Pettis Bridge Sunday to commemorate the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” the Civil Rights flashpoint that helped spur the passing of the Voting Rights Act and made Selma one of the most famous small cities in America. But on Monday, when President Barack Obama and 100,000 other visitors are gone, Flanagan will return to Selma High School, a school that is just about as black as the one her predecessors attended in 1965, when the city was by law segregated.

In the ’50s and ’60s, schools were as critical a battleground for racial equality as the ballot box. Selma, with the prodding of federal courts, opened an integrated high school just a few years after reckoning with the most devastating form of racial hatred. Schools across the South integrated increasingly in the 1970s and 1980s, so that by 1988, fewer than a quarter of black students were attending schools with a 90% or greater minority population, according to the Civil Rights Project, a research group based at UCLA.

And then that trend began to move backwards. In some communities the dream of integrated schools faded slowly as courts phased out laws mandating integration. In Selma, the dream shattered all at once in a moment so racially charged that, decades on, many locals still don’t like to talk about it. As of 2011, 34% of black students in the South attend nearly all-minority schools, and the figure has been ticking up steadily over the last two decades. In Selma 95% of black students in the public school system attend such institutions. These schools, which are often doubly segregated by poverty, tend to have fewer resources and lower achievement rates than their majority-white, middle-class counterparts.

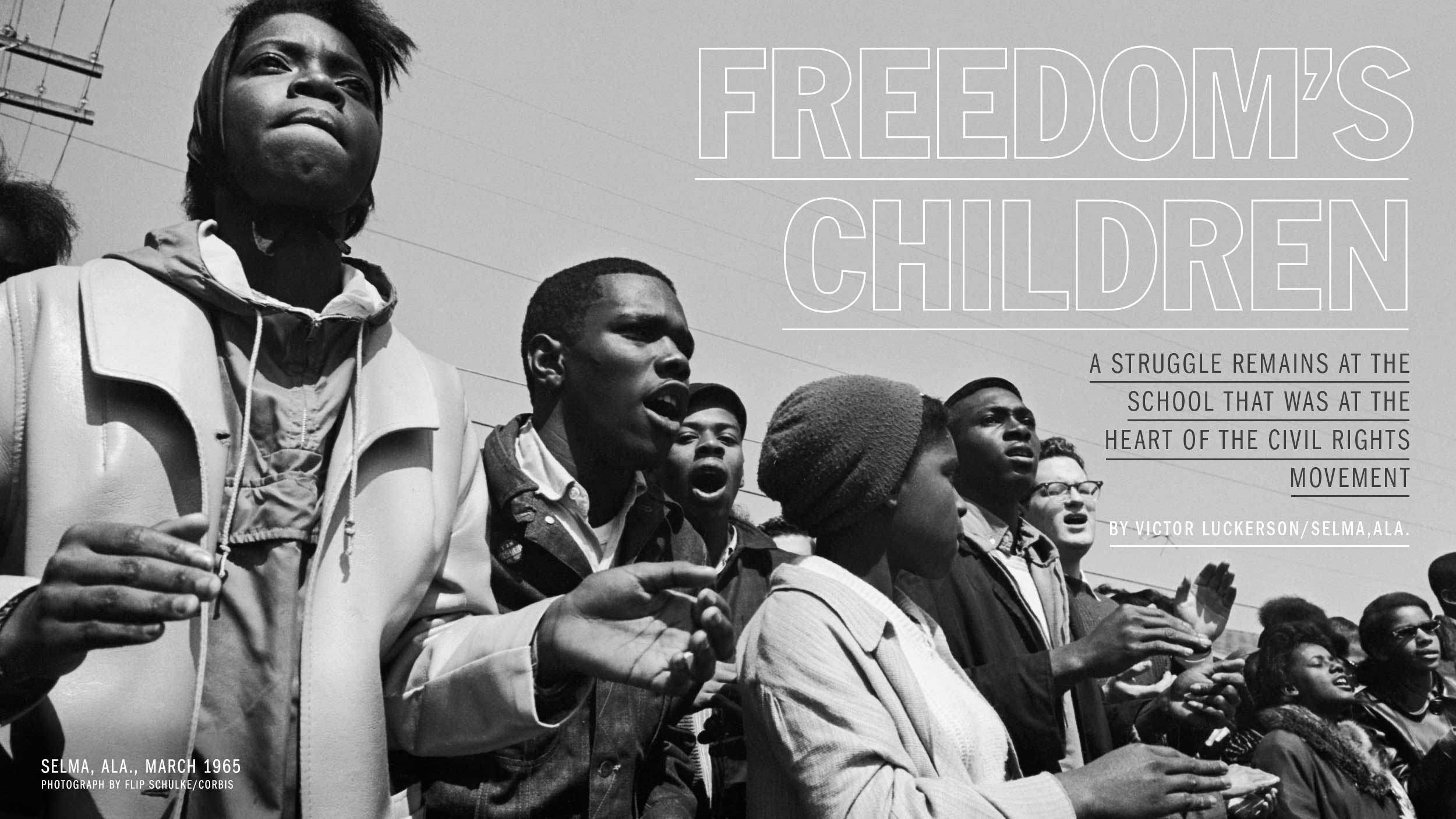

It’s an unexpected outcome for the men and women who attended R.B. Hudson High School, the all-black predecessor of Selma High. As kids, they compelled Selma, and in turn, America, to grant them equal rights. Because theirs were the bodies that crowded city streets, drained the school system’s coffers and took blows on the bridge, they’re commonly known as the foot soldiers of the Civil Rights movement. But here in town, they also have another name for this generation: “Freedom’s Children.”

Selma already has its fair share of famous places, from its infamous bridge to Brown Chapel, a headquarters for Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference during their 1965 voting rights campaign. If Henry Allen, Selma’s 70-year-old retired fire chief, has his way, a squat school building tucked in one of the town’s historically black neighborhoods will one day join the company of these landmarks.

R.B. Hudson High School, named for a prominent local black businessman and educator, was the lone black public high school for Selma teenagers in the 1960s. Despite being separate from the white high school, Hudson High provided a quality education, students of that era say. The school offered a thespian society as well as a library club. Its choir toured nationally and performed at the World’s Fair in New York in 1965. “I don’t think we ever felt we were quote-unquote ‘disadvantaged,’” says Eleanor Faye Martinear, a former member of the youth choir.

Henry Allen was an 11th grader at Hudson High in 1963 when he met Bernard Lafayette, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, at a local church meeting. Lafayette believed Selma was well placed to begin organizing blacks in campaigns to end segregated businesses and establish the right to vote. “All we knew was segregation,” Allen says today, sitting in the room that once served as Hudson High’s cafeteria. “We were kids living in a Jim Crow society. He was talking about all the rights we had not received and how we were second or third-class citizens.”

Allen and other teens took Lafayette’s message back to Hudson High and began discreetly recruiting more kids to attend mass meetings, sit-ins and protests. The so-called student “foot soldiers” handed out voter registration forms, helped prepare blacks in the community for literacy tests, and picketed the courthouse in protest of unfair voting laws. “They were the shock troops of the movement,” says Alston Fitts, a Selma historian who has written a book about the city.

Students, placed at the forefront of the protests, had less to lose than their parents did. “The adults had jobs,” says Charles Mauldin, who served as a student leader during the protests. “Many of them lived on white people’s property. There were some very severe social and economic consequences if they marched first.”

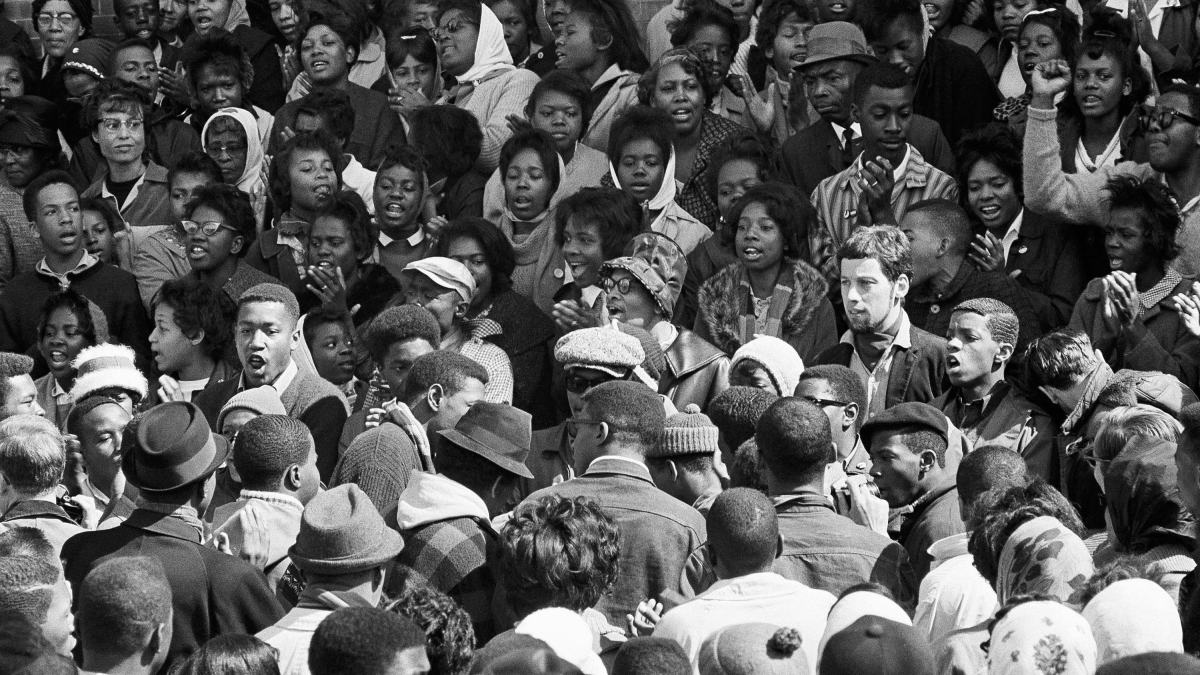

Student agitation in Selma reached its peak in early 1965 with the arrival of Martin Luther King, Jr. On Feb. 7 of that year, 946 students were absent from Hudson High, according to Selma-Times Journal, about two-thirds of the school’s total population. Such mass absenteeism cost the school system $1,000 per day in lost revenue because the state allocated education funds based on attendance. Police arrested so many students during this period that city jails overflowed and some students were shipped off to the Camp Selma, a squalid county prison camp.

The protests culminated with the confrontation on “Bloody Sunday.” Mauldin, who stood in the third row of marchers on the bridge, recalls the thwack of future Congressman John Lewis’s head being struck by a state trooper’s club. “I’ll never forget that sound,” he says. After he escaped the bridge, his main priority in the ensuing chaos was convincing people not to riot. “That was their attempt to try to get us to react violently to justify their assault against us.”

Tempers were calmed. The protesters completed their march to Montgomery two weeks later. The Voting Rights Act followed that summer. Over the next several years several other racially unequal institutions in the South were slowly dismantled, including the school system.

A Changed Selma

race Hobbs and Althelstein Johnson were both 24-year-old, Selma-born English teachers when they started working at A.G. Parrish, the town’s white high school, in 1969. But their experiences couldn’t have been more different. Hobbs graduated from Parrish, and her return to the school felt like a homecoming. Johnson, meanwhile, felt like a fish out of water. She was constantly scrutinized as one of Parrish’s first black teachers. Eventually the pair would co-sponsor the National Honor Society at a school that served both whites and blacks.

race Hobbs and Althelstein Johnson were both 24-year-old, Selma-born English teachers when they started working at A.G. Parrish, the town’s white high school, in 1969. But their experiences couldn’t have been more different. Hobbs graduated from Parrish, and her return to the school felt like a homecoming. Johnson, meanwhile, felt like a fish out of water. She was constantly scrutinized as one of Parrish’s first black teachers. Eventually the pair would co-sponsor the National Honor Society at a school that served both whites and blacks.

In 1970, Selma fully integrated its school system, moving R.B. Hudson students over to the previously white Parrish building and renaming it Selma High School. The change did not come from any kind of municipal change of heart–the 1967 Supreme Court decision Wallace v. United States mandated that all of Alabama’s school systems comply with a set of strict desegregation guidelines.

Despite the town’s racial wounds, black and white students began attending the same school without significant problems. The biggest arguments the teachers can recall were over choosing school colors and a mascot. Blacks and whites mixed in classes and in places like the debate club, which became a point of pride for the school. A wide slate of Advanced Placement courses was offered. Selma High produced the city’s first black mayor, James Perkins, and the state’s first black Congresswoman, Terri Sewell.

“The opportunities for students were broader than what they could get elsewhere,” says Hobbs. Whites who had left the public school system during forced integration began returning in the ’80s. “It was the kids themselves who were saying, ‘I want to go to Selma High.’”

Still, Selma had not created some kind of post-racial paradise. Whites and blacks still lived in separate neighborhoods, and whites continued to control the mayorship, the city council and the school board, despite the fact that blacks were a growing majority of the city’s population. Blacks worried about the leveling system used in Selma schools, which placed students on different academic tracks based on their ability. Though assigning levels was supposed to be done using objective standards, some students were placed in classes based on subjective assessments by teachers or guidance counselors (though parents had the ability to change their child’s level), according to a report by the Alabama Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. A larger percentage of the white students tended to end up in high-level courses than the black students did.

These simmering issues came to boiling point in 1990, when the school board chose not to renew the contract of Norward Roussell, the system’s first black superintendent, citing poor managerial and administrative skills. The vote was cast strictly along racial lines—blacks supported Roussell’s efforts to make the tracking efforts more transparent, while some whites on the board viewed his style as abrasive. When Roussell was let go, the black school board members walked out of the meeting.

Protests erupted at City Hall, and students staged a five-day sit in at Selma High’s cafeteria. The entire school system was shut down for a week. Alabama Governor Guy Hunt sent 200 National Guardsmen to Selma to maintain order when the schools reopened.

Amid this turmoil, whites abandoned the public school system en masse. By the end of the school year, more than 560 whites had left Selma’s public schools, with 300 leaving Selma High alone. Some that remained complained of heightened racial tensions and increased fights that specifically targeted white students. Eventually nearly all whites would leave Selma High, opting for local private schools that had been opened shortly after “Bloody Sunday” as a direct response to desegregation or boarding schools in other cities. Some simply packed up and moved to neighboring towns.

The school hasn’t been the same since. “It changed Selma for the worse, and it almost took us back to the ’60s in the level of racial division,” says Kimesha Alvarado, who was a student protester at the time. “A lot of relationships were severed, and it’s still strained to this day.”

Selma’s Future

oday Selma High looks nicer than many college campuses. The sprawling new $27 million building, opened in 2012, features a modern auditorium that has become a popular spot for community events. Uniformed students walk in hallways painted a cheerfully bright yellow. The school has two gymnasiums, as well as a collection of iPads that students can use in class.

oday Selma High looks nicer than many college campuses. The sprawling new $27 million building, opened in 2012, features a modern auditorium that has become a popular spot for community events. Uniformed students walk in hallways painted a cheerfully bright yellow. The school has two gymnasiums, as well as a collection of iPads that students can use in class.

But there are still signs of the school’s struggles. Selma’s city school system was taken over by the state Board of Education in 2014 after an investigation uncovered sexual misconduct by a Selma High teacher and violations of state testing policies. The debate team and the drama club are gone. Students have to walk through a metal detector every day to enter the building. Between classes, teachers and security guards stand patrol to monitor kids, and minor infractions can easily bring on detention. Outside near the athletic fields sits a small memorial to honor Alexis Hunter, a Selma High student who was shot and killed right by campus in 2013 during a robbery for her cell phone.

Despite the technology that abounds, per pupil spending in Selma was $8,100 in 2012-2013 school year, ranking 104th among Alabama’s 134 public school system, according to data from the state’s Department of Education. Two-thirds of students qualify for free lunch, which means their families live at or just above the poverty line. In some classes, there aren’t enough books for all students, so teachers keep textbooks in class and print off handouts or assign online coursework for students to use at home. In 2013, a third of students didn’t graduate. In Prattville, a mostly white suburb nearby, the main high school’s graduation rate was 83% that year.

But Selma is not alone. These are common struggles for modern segregated schools, which are increasingly the types of schools where minorities gain their education. And it’s not just a problem for the South–more than half of black students in the Northeast attended schools with a nearly all-minority population in 2011, even though 60% of the students in the region are white, according to the Civil Rights Project.

Attending desegregated schools offers measurable improvements in black students’ lives. Each year a black male attends a desegregated school increases his chances of graduating by as much as 2.9 percent and his annual earnings later in life by as much as 5 percent, according to a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Blacks’ chances of living in poverty or going to jail also decrease when they attend desgregated schools.

Gary Orfield, co-director of the Civil Rights Project, argues that such schooling has benefits for whites, as well. “Most Americans haven’t really registered the fact that kids that are growing up now are going to be living their lives in a society without any racial majority,” he says. “Being able to live and work across racial lines and understand other groups is a really crucial skill for the future in the United States.”

Kids understand the importance this skill will play in their lives. “If you live in Selma all your life and all you know is going to Selma High, and you’re in a school full of people who look just like you, it’s going to be kind of hard to change and adapt when you move on to different chapters in your life,” says Paul Alvarado, a current Selma High senior and the class homecoming king.

Aubrey Larkin, the school’s new principal, hopes to help fix Selma High. He’s the third person to hold the position in the last five years. “One obstacle has been to overcome our past,” he says. “The state in which we are right now–that’s not how the story is going to end for Selma High.”

In his first year, Larkin has added a wrestling team to the school’s extracurricular activities and reorganized the classrooms so that subjects are clustered in different wings of the school. In 2014 Selma High’s graduation rate jumped to 80%, giving Larkin some potential momentum to seize. He and many others would like to see whites return to the public school system, but the city’s white population has been shrinking steadily (Selma, a town of 20,000, is now 80% black). “I’d thank God on my knees if Selma High became integrated again,” says Alston Fitts, the Selma historian, “but I think it’d have to be the Lord’s doing.”

Henry Allen’s campaign to get the students of R.B. Hudson recognized has started to payoff. He filled out the application himself to get the building placed on Alabama’s historic register in 2013, and now is in the process of applying for the National Register of Historic Places. Just days before the “Bloody Sunday” commemorations, Allen flew to Washington to meet President Obama at a reception honoring Civil Rights activists. “He commended us on the fact that we were foot soldiers,” Allen says. “He knew for a fact that if it hadn’t been for us, he would not be in the White House.”

Less than a mile away from this newly minted landmark, the students at Selma High are trying to work out where they fit in a country that is supposed to be far removed from the challenges that faced the kids who attended Hudson a half century ago. “I’ve heard so many times people say, ‘Oh, Selma’s the heart of the Civil Rights movement,” says Eric Jackson, a freshman at Selma High. “As much of a history as it has behind it, it should have more things than it does have. It should be in a better condition than it is. I think it’s good that all these people are coming here to celebrate, but what happens when all those people leave?”