By Karl Vick | Photographs by Lisette Poole

The shortest route from Cuba to the U.S. is 90 miles. But that’s across the Florida Straits, and Liset Barrios gets nervous on a boat. So on May 13, she boards Copa Airlines Flight 295, setting off the long way around—the really long way. The journey covered 8,000 miles, took 51 days and, along the way, illuminated an obscure byway in this historic wave of human migration. The U.N. says some 244 million people live outside their home countries, most as legal guest workers in nearby nations. About 21 million are refugees fleeing war or persecution. Several million more—no one knows the precise number—make their way underground, “irregular migrants” trying to stay out of sight en route from a poor place with scant opportunities to a richer one, with more.

Liset and her neighbor Marta Amaro, who traveled with her, are in a semiprivileged subset of irregulars. Since they are Cubans presumed by U.S. law to be suffering under the yoke of communism, they would actually be welcomed in America when they arrive—provided they come by land. The problem is that none of the countries close to the U.S. allows a Cuban to enter without a visa.

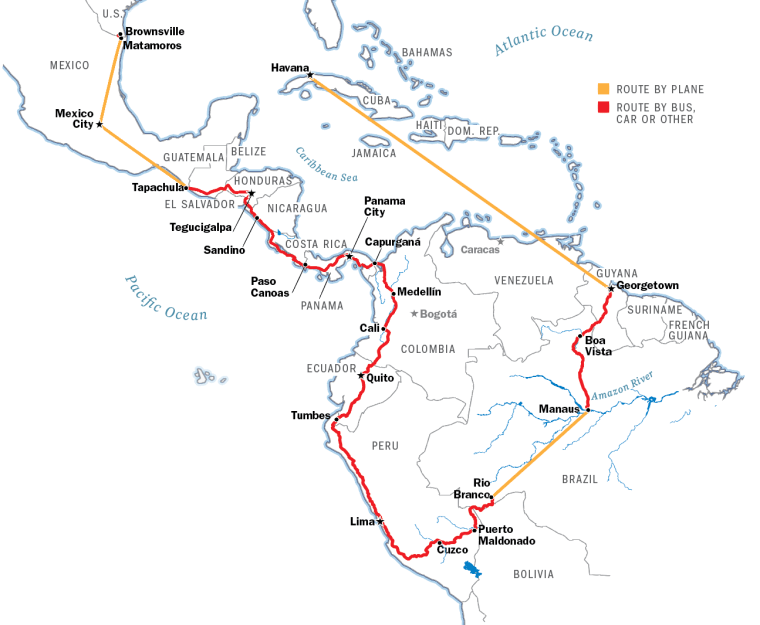

The Journey from havana

So it is that Liset, Marta and the photojournalist Lisette Poole land at 1:39 p.m. in Georgetown, the capital of the tiny South American country of Guyana, the nearest country open to Cubans. Their plan is to get a hotel and scout around for a smuggler, but they don’t even have to leave the airport. While disembarking, another Cuban tells them he has a smuggler waiting outside. “It’s something that’s already there,” Liset says, of the river of migrants the women enter at that moment. “And you have to have the luck of being there at the right moment to get into it so that everything flows.”

That very night, they ride in a van 18 hours to Brazil—the more direct route toward the U.S., northwest across Venezuela, having been ruled out because the country is wildly dangerous. (The migrant river follows the path of least resistance.) They cross the border into Brazil by canoe, then make their way to Manaus, deep in the heart of the rain forest. There they board a plane to southwest Brazil, saving 22 hours overland, and hire a taxi to the border of Bolivia, a remote corner of which they cross en route to Peru.

The bus over the Andes to Lima is $150. Thus far, each has spent $2,300 of the nearly $8,000 the journey will end up costing per person. Most of the way, Liset, 25, pays for Marta. The younger woman has a boyfriend in Chicago, who fell for Liset during a visit to Havana. In Cuba, tourists use a special peso worth 26 times the currency used by ordinary Cubans.

By befriending male tourists with money to spend—an arrangement that often shifted from girlfriend to escort—Liset managed to live relatively well, after once living in a shipping container. Marta, 53, made $5 a day working in cafeterias, hospitals and, for a time, an asylum. Both women wanted a better life, and then the boyfriend offered to bring Liset north. “Our plan was to help each other,” Marta says.

In the way of modern migrants, the women travel with smartphones, touching base with family when they get wi-fi, which the hostel in Lima has. At dusk that day they board a bus toward Ecuador, where Liset talks their way past immigration agents. The first bus in Ecuador is crowded with Haitians, who after the 2010 earthquake also got a temporary dispensation to enter the U.S. There are even Bangladeshis, who began their journey nearly 11,000 miles away.

They cross into Colombia on horseback, negotiate past a military patrol and walk up a hill to a chicken restaurant, where the next coyote—Latin American slang for people smuggler—is waiting. Every move the migrants make is at the instruction of coyotes, who text photos of the next smuggler to the migrants so they know whom to look for at the next stop. “In every country, they would tell you to hide,” Liset says, “but I think it was their way to scare you, so you would feel afraid if you were out of their hands.”

Colombia, riven by both corruption and conflict, is notoriously difficult, yet the migrants flow on. That night, after a day in a “stash house,” Liset and Marta join a dozen others under the tarp of a truck loaded with potatoes. The photographer Poole rides up front with the driver and a coyote. “They swap migrant stories like camp counselors,” she writes in her notes.

At a motel, the travelers are grouped by nationality. They take a bus to Medellín, wait days, then board an overnight bus toward Panama, tension rising as South America narrows toward the isthmus. They ride motorcycles to a boat, cross an inlet in a two-hour trip, switch to a horse and buggy and shower in a preschool before reaching a camp, where they meet Cubans who were on the jet from Havana.

They have run out of road. Panama begins at the Darién Gap, a dense jungle 30 miles wide and 100 miles long. They sleep in camps with guides and young men from Nepal and the Punjab, evidence it’s not just Latin Americans trying to enter the U.S. from the south. (So far this fiscal year, 448 Armenians have presented themselves at crossings; the Border Patrol has caught 2,130 Chinese and 1,863 Russians.)

The trek is brutal, running over steep hills called Goodbye My City and Hill of Death. “I wanted the earth to swallow me,” says Marta, who hurt her leg the first day. “I didn’t think I was going to make it.”

They travel due west, crossing the same curving river again and again. The women are separated, and Poole moves with a group of 50 others. That night the rain washes away her things. Reunited, the three end up, on the sixth day, presenting themselves to Panamanian officials, who check their fingerprints against terrorism and criminal databases then allow everyone to move on.

The Central American leg feels even more chaotic. The coyote in Costa Rica has green hair and laughs as she blows past officers. Marta leaves the group after a quarrel about money. She’ll make it to the U.S. herself, 12 days behind Liset and Poole—who enter Nicaragua on horseback, then hike another jungle trail marked by red ribbons on teak trees; people drink water from puddles and sleep standing up. They end up crowded in an SUV with only a narrow band cut in the window tinting, cross a river into Honduras on foot, then enter Guatemala the same way. Mexico is reached on a raft.

The next day, Liset takes a flight to Mexico City, then another to Matamoros, where she presents herself to the U.S. agents to the border at Brownsville. There she is given a permit. A day later, July 3, she lands at Chicago’s O’Hare airport, the beginning of her American journey.

The boyfriend is late.