The Scientist

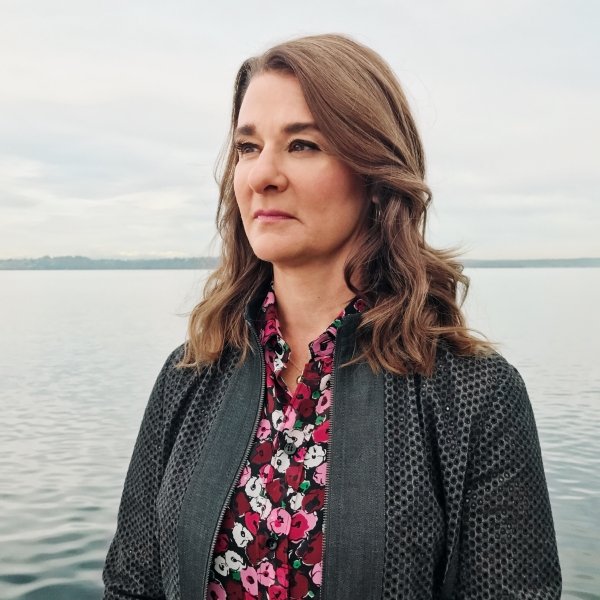

Elizabeth Blackburn

First woman to become president of the Salk Institute

Interview

‘Being visible is important.’

I grew up in a small town in Tasmania, and I just loved animals. We had so many. At some point I counted in our house budgerigars, canaries, a dog, a cat, guinea pigs, rabbits, bantams and chickens. I liked looking at nature—trees and plants and ants and jellyfish. Living things just grabbed me, which turned into loving the idea of understanding how they work. I read a book about molecules and figured that that was the secret of life, and I determined that I was going to work with the molecules of life.

I was kind of an ornery character as a child—one of those kids who didn’t like to be told to dress up or how to do drawings. I have a strong memory from kindergarten: I was drawing a big black locomotive, and my teacher said to me, “Don’t use so much black.” I was really mad. It was my locomotive—how dare anybody tell me how to draw it? I remember being angered that somebody would have another idea about how my locomotive ought to look. I was also a child who realized that I shouldn’t make too much fuss—I was fairly well-behaved—but I had a streak of independence that I think put me in good stead for science as a career from that point onward.

I recall visiting the home of friends, and a man who was present asked me what I wanted to do one day. I said, “I’m going to be a scientist.” And he said, “What’s a nice girl like you doing going into science?” I was shocked and so mad that I didn’t know what to say in response. So I kept my mouth shut, but I was all the more determined. In a way, I’m quite grateful to that man, because he made me realize that science was something I really wanted to do and that nobody was going to deflect me.

When I first began, in the 1970s, women in the life sciences were pretty unusual. Over the years, I started to notice that we had become less unusual. Then in the 1990s, I became the chair of a science department at a big medical school. I remember going to the first meeting of all the chairs—clinical departments and basic sciences departments. I walked into the room, where I was the only woman, and I had this feeling that I was back in the 1970s. It struck me that, at that career level, women were much, much less in evidence and much, much less likely to have a high executive position than they were to be a scientist or even a physician for that matter. Biology is very complex, and it requires different depths of thought. If you cut out 50% of the world’s minds from the problems of science, then you’re losing a huge resource. You don’t solve complex problems nearly as well.

Every woman thinks about balance in life. Work norms make it hard for you to be active in your career, which you love, and also manage the demands of family. Don’t be afraid to ask for advice, because you’ll find that there are possibilities that you didn’t know about—career structures that will allow you to build in family time, or just practical advice. One is always surprised by how much people want you to succeed.

I sometimes see the glass ceiling in the number of women who get nominated for recognition. Men seem much more likely to be recognized than women, even if they are working on a team with a woman. So we have to say, Really? Is it because women contributed so little? There’s plenty of evidence against that. When somebody like me can be visible as a Nobel laureate, it says, Look, there is such a possibility. There are only eight living women who have Nobel Prizes in the sciences, and I think we ought to be seen. If you’re a young scientist and the Nobel laureates all look the same, you kind of get the sense that, Well, that’s not something I can see myself as. Being visible is important.

Blackburn, president of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies since 2016, won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her DNA breakthroughs.