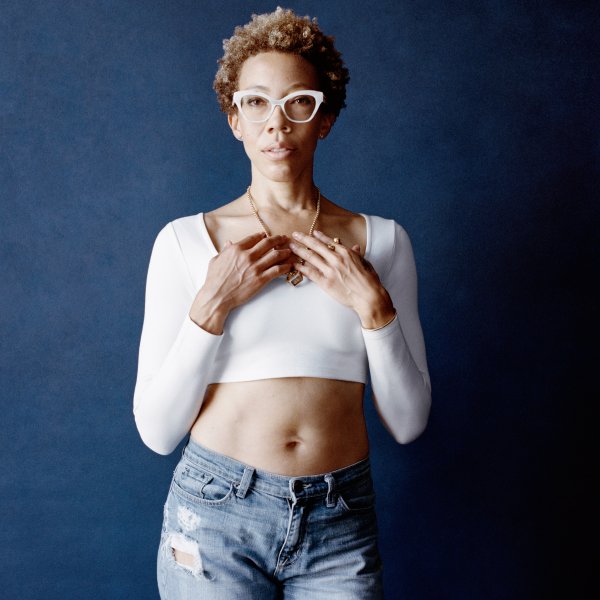

The Oceanographer

Sylvia Earle

First woman to become chief scientist of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Interview

‘Men and women living underwater together wasn’t going to fly.’

The first time I went underwater, I was 3 years old, and I was knocked over by a wave. The ocean got my attention. Years later I had a chance to breathe compressed air underwater, through a copper diving helmet. Our next-door neighbor in Florida was a sponge diver, and my older brother and the sponge diver’s son conspired to “borrow” the equipment: the helmet, a compressor and a hose that connected the compressed air. I just wore a bathing suit and went barefoot, so my feet kept floating up. That was my first experience. A year later, in 1953, I used scuba for the first time, with two words of instruction: “Breathe naturally.” It was glorious—I could get acquainted with the fish and be free of any connection to the surface. It was like flying. What I love about the ocean is you never know whom you’re going to see or what you’re going to do, but it’s always going to be good. It’s always going to be a thrill.

When I was in high school, science was not a particularly attractive field for many young women. It seemed like a guy thing, but I loved it. I wanted to be an ecologist, somebody who looked at how the whole system works. When I began college, I was often the only woman in a class.

I came along at a time when women were just beginning to be accepted as competent scientists and engineers. Having women on ships was not a particularly welcomed thing. The U.S. Navy took a long time to allow women. Now there are women captains, and you finally see the idea of brain over brawn, even on commercial ships. It was and is about, Can you do the job? Are you able? Can you handle this machinery? But that wasn’t always the way.

The cultural bias is what it is. Men and women are different, and the society of men as leaders has predominated the society in which I came along. It’s still very much there, but it’s getting better. Women are every bit as intellectually competent as our male counterparts.

On one of my first oceanographic expeditions, in 1964, I did not yet have my Ph.D. (In fact, it took me 10 years to earn a Ph.D. because I got married and had two of my three children along the way.) I was the only woman with 70 men for six weeks at sea in the Indian Ocean. I had never been west of the Mississippi River before I went halfway around the world to the Indian Ocean. But then the headline on an interview I did, which ran in the Mombasa Daily Times, was “Sylvia Sails Away With 70 Men. But She Expects No Problems.” It was my first real interaction with the press. I don’t know what problems they thought I might have. To my mind the goals were: keep a sense of humor; don’t expect favors; do what you’re there to do as a scientist. In an atmosphere where other people may expect you to be treated differently, you try not to be treated differently. I took being a scientist very seriously. I still do.

Later, I was a scientist at Harvard when I noticed a paper on the bulletin board asking if anyone would be interested in living underwater as a scientist for two weeks in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The idea was to come up with a project that would be reviewed by scientists at the Smithsonian Institution and sponsored by the Department of the Interior. No mention was made about having to be a guy, but it was clear that no one expected women to apply. But some of us did. And the rest is history, if you will.

The idea of men and women living underwater together wasn’t going to fly, but they allowed us to have a women’s team, and I was the leader. That put me in the hot seat again. We attracted attention from all around the world. The men who did this, they were called aquanauts. The women, we were aqua-babes, aqua-chicks, aqua-naughties. But we didn’t care what they called us, as long as we had a chance to go.

We had a wonderful time. We spent a lot of time in water, day and night. I’d been diving, of course. I had more than 1,000 hours at that point, but just in and out—20 minutes or sometimes only five or 10 minutes at a time. Here we had 24 hours a day for two weeks, in and out at our will. Once we were underwater, it was just freedom. We wanted to be out there getting acquainted with the fish on their terms.

People asked us all kinds of silly questions—Did we use a hair dryer? Did we wear lipstick?—but we used that opening to explain the nature of the ocean: how beautiful it is, how vulnerable it is. How, even back then, there was evidence that what we were doing to it was causing problems. It wasn’t pristine—there had already been a reduction in some of the fish that we would normally see on a coral reef, for example—but compared with today, it was glorious because of the variety. Today 90% of many of those fish are just gone.

Our time down there was breathtaking. It was just beautiful. The fish weren’t afraid of us, even though they’d seen primates in the water before—people there to spear them, for instance. But we weren’t there to kill them, so with us, when we behaved ourselves and treated them the way they liked to be treated, with dignity and respect, they were friendly. The fish were curious about us. That’s when I thought, Do unto the fish as you would have fish do unto you.

And when you treat them like that, it’s amazing what you can see. It’s true when you deal with humans that way too.

Earle is president and chair of Mission Blue, an organization that advocates for legal protection and conservation of the world’s oceans.