-

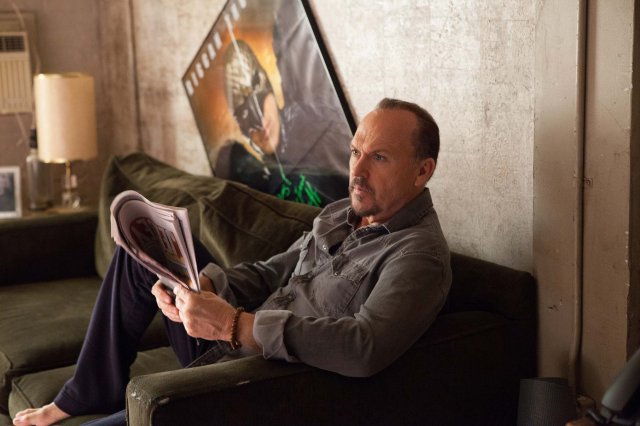

Birdman

20th Century Fox Sixtyish actor Riggin Thomson (Michael Keaton) hates that he is remembered only for a comic-book movie hero, Birdman, that made him a star decades earlier. He figures that headlining and directing a Broadway play based on a Raymond Carver story will convince the world of his serioso chops. But when nearly everything goes wrong in previews, Riggin realizes he can trust only the Birdman voice in his head. Assembling a dynamite cast (Edward Norton, Naomi Watts, Zach Galifianakis, Emma Stone) and employing Gravity cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki to shoot the two-hour story as if it were one continuous take, director Alejandro G. Iñárritu turns a familiar backstage dramedy — say, All About Eve plus All That Jazz times Fellini’s 8½ — into a spec-technical tour de farce. Keaton, who played Batman in two Tim Burton movies, locates Riggin’s frantic weariness, which could sag into suicidal defeat or ascend into mad apotheosis. Not to worry: the actor and the movie end up soaring.

-

Wild Tales

Sony Pictures Classics Passengers board a flight for which they have all received free tickets. Slowly they realize that their mysterious benefactor is a man named George Pasternak, whom each of them had wronged in some way — and that he is in the cockpit about to crash the plane. A hijacking story with a weirdly effervescent tang, this is the first of six short fables in an omnibus comedy from Argentinian writer-director Damián Szifron. Animosity simmers and boils hilariously in episodes set in a roadhouse diner, on the open highway, in a DMV office, among the corrupt members of a rich family and at a wedding ceremony where the bride learns her new husband has had affair with one of the guests. Produced by Pedro Almodóvar, and playing like a volume of short stories somehow coauthored by Ambrose Bierce and Roald Dahl, Wild Tales builds recognizable grudges into tales of apocalyptic revenge. It’s also the year’s most fearlessly funny film.

-

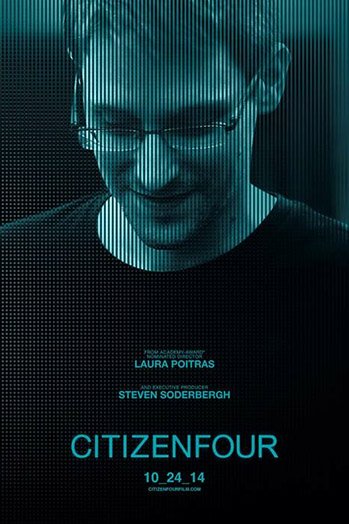

Citizenfour

Radius/The Weinstein Company Calling himself Citizenfour, Edward Snowden sent encrypted email messages to doc filmmaker Laura Poitras that hinted at extraordinary revelations about the National Security Agency’s database on U.S. citizens. In a Hong Kong hotel room in June 2013, the Booz Allen IT analyst met Poitras and journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill to spill his and his computer’s guts. The subject of this fascinating, edifying and creepy film has a nerdish star quality: poised and articulate, he’s also more than a little anxious. Snowden correctly anticipates what’s in store for him — official pariah status in the U.S. — and makes clear that the need for the public to know the range of NSA eavesdropping is worth the price he will pay. The glare of Poitras’s camera gives the young man a ghostly pallor; he could be a specter reaching out from the other side to warn the living. A true-life spy thriller and horror movie, Citizenfour is also history in the making: a portrait of a man at the very moment he chooses to enrich and darken Americans’ understanding of what their government knows about them.

-

Nightcrawler

Open Road Films “Think of our news,” says a producer at an L.A. TV station, “as a screaming woman running down the street with her throat cut.” Lou Bloom, a freelance news cameraman played by Jake Gyllenhaal with the smiling stare of a deranged Boy Scout, takes that advice and shoots video of grieving widows, home-invasion casualties and human roadkill. You want to see this stuff, up-close and purple, do you not? Lou’s the guy who gets it for you. Imagine Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver worming his way into Paddy Chayefsky’s Network and you have writer-director Dan Gilroy’s ’70s-going-on-right-now mix of psychological portrait and media satire. Prowling an after-dark L.A. brought to gorgeous, menacing life by ace cinematographer Robert Elswit, Gyllenhaal ratchets down his usual fretful-puppy winsomeness to create an ornate, eloquent vessel for Lou’s hollow charm, careering zeal and pestilential value system.

-

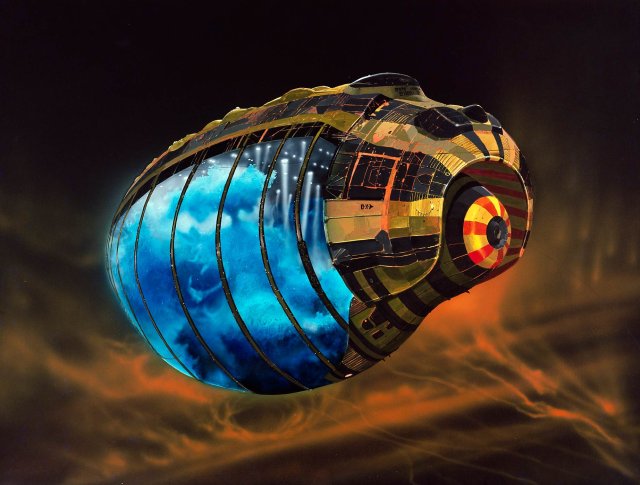

Jodorowsky’s Dune

Sony Pictures Classics In sweeping gestures and urgent broken English, Alejandro Jodorowsky exclaims, “Movies have heart — boom, boom, boom! Have mind [he mimes lightning bolts from his brain]. Have power [he points to his genitals]. Have ambition! I want to do something like that. Why not?” At 84, four decades after he prepared a hallucinogenic adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science-fiction novel Dune, the Chilean-born Mexican director is still heartbroken that the project died when his producer came up $5 million short on the $15-million budget. A few years later, George Lucas spent $11 million making Star Wars, and the fantasy-film genre went retro instead of luxuriously wacko. Doc director Frank Pavich buttresses his profile of the still-vital and charismatic Jodorowsky with contributions from the old Dune team, including writer Dan O’Bannon and concept designers Chris Foss and H.R. Giger (all of whom world work on Ridley Scott’s Alien). The message to take from this love letter to the cinematic ambition of the ’70s: movies once had brains and balls, and lost them.

-

Goodbye to Language

Wild Bunch In a banner year for 84-year-old visionaries, Jean-Luc Godard issued his first 3-D feature, a skeptical phantasmagoria that proves the unstoppable innovative verve of the auteur who set movies on their modernist course with his 1960 Breathless. When most other directors stopped modernizing, Godard went further, into a film-essay form that lays his cantankerous ideas about life, love, politics and film history over the smidge of a story — here, the romantic debates of a youngish, often nude couple (Héloise Godet and Kamel Abdeli). As if he were making the first 3-D movie experiment, Godard shows nature in violent, supersaturated colors and, in one scene, plays with overlapping images: close one eye and see a man in the foreground, close the other and see the woman in the back. The real star is Godard’s dog Roxy, a mournful observer and a great natural actor who embodies Darwin’s observation that “A dog is the only thing on earth that loves you more than he loves himself.” This latest Godard may be hard to love, but it probes, confounds and exhilarates in equal and unique measure.

-

Lucy

Universal Most big summer movies are handsome, muscular and dumb; in a word, Transformers. Luc Besson’s globe-trotting thriller, about a woman empowered and imperiled by the infusion of a powerful new drug into her nervous system, is different: it kicks ass and takes brains. Besson provides his usual fights and car crashes, before swerving toward a climax of Mensa movie madness in the spirit of a berserk 2001. The French writer-director, who has often put women at the center of his action movies (La femme Nikita, The Professional, The Fifth Element), here creates a heroine whose rapidly expanding abilities make her the world’s most awesome weapon — in the process, promoting Scarlett Johansson from an indie-film icon and Marvel-universe sidekick to the movie superwoman she was destined to be. Taking place in less than a day, while simultaneously synopsizing three million years of human evolution in a hurtling 89 mins. of screen time, Lucy is the year’s best, coolest, juiciest, smartest action movie.

-

The LEGO Movie

Warner Bros. The challenge to directors and cowriters Phil Lord and Christopher Miller: transform the blocky LEGO figures, with painted faces and no arm or leg mobility, into charming or rapacious characters a viewer can instantly accept and believe in. That they did. Worker drone Emmet (voiced by Chris Pratt of Parks and Recreation and Guardians of the Galaxy) gets mistaken as the Special One, the Neo of the LEGO matrix, by a cadre of underground rebels bent on overthrowing the evil President Business (Will Ferrell). “Anti-capitalist” was the phrase that Brietbart.com applied to this comedy about the nightmare merger of big government and predatory commerce — somehow ignoring that it’s also a feature-length commercial for the world’s largest toy company. Politics aside, The LEGO Movie is a hoot, and a beaut. Shot in a CGI format that mimics stop-motion animation, it has an aptly rough, faux-primitive look, as if some brilliant kid had made a madly elaborate home movie the whole world could love. The sequel comes in 2018.

-

Boyhood

Diaphana Films In what might have been a gimmick but was really a stroke of genius, Richard Linklater began shooting Boyhood when its leading actor, Ellar Coltrane, was a first-grader and each succeeding summer shot a new segment involving Coltrane’s Mason and his Texas family: mother Olivia (Patricia Arquette), father Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke) and elder sister Samantha (the director’s daughter Lorelei). Mason’s evolving life has its difficulties but few extremities; it unfolds rather than exploding in reality-TV’s manufactured traumas. A home movie of a fictional home life, an epic assembled from vignettes, Boyhood shimmers with unforced reality. To watch it is to page through a family album of folks you just met, yet feel you’ve known forever. This is life as most of us experience it, and which few movies document with such understated acuity. Embrace each moment, Linklater tells us, because it won’t come again — unless he is there to record it, shape it and turn it into an indelible movie.

-

The Grand Budapest Hotel

Fox Searchlight Monsieur Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes) flawlessly executes his job as concierge at the Grand Budapest Hotel in the Republic of Zubrowka during the political upheavals of the 1930s. Intoning romantic poetry he may have made up on the spot, he attends to the sexual whims of his rich old-lady clients; or, as he says, “I go to bed with all my friends.” Amour and mortality, romance and horror, comedy and tragedy duel to a sumptuous draw in Wes Anderson’s rich torte of a movie — perhaps the most seductively European film ever made by a kid from Houston, Texas. A dizzyingly complex machine whose workings are a delight to behold, the movie has a wry smile for frailties, a watchful eye for tyranny and a heart that, under the circumstances of this dark, fanciful tale, must be called heroic. This is not just an amazing contraption, though it is that; it’s a real, funny, sad movie, whose performances (from Fiennes, Adrien Brody, Jeff Goldblum, Tilda Swinton and dozens of others) are as alert and elegantly composed as the décor. Grand isn’t good enough a word for this Budapest Hotel. Great is more like it.

Read next: The Top 10 Best Movie Performances of 2014