As clean energy rises, West Virginia looks past Trump’s embrace of coal to what comes next

By Justin Worland/Charleston, W.Va.

Photographs by Peter van Agtmael—Magnum Photos for TIME

It was a cloudy February afternoon in Charleston, W.Va., but the mood inside the city’s civic center was downright celebratory. As bow-tied waiters mixed drinks and manned a buffet of shrimp cocktail and roasted meat, the hundreds of members and guests at the annual meeting of the West Virginia Coal Association mingled with a lightness that would have been unthinkable just a year before.

After years of steady decline, the price of a key type of coal used to make steel doubled in 2016, largely due to a spike in demand from China. This led some mines to hire more workers and prevented others from laying off workers. Meanwhile, the state elected Jim Justice, a billionaire coal baron, as governor, and the nation installed Donald Trump as President. Both men wooed West Virginia voters with the promise of more mining jobs and fewer regulations. For an industry in need of a boost, it might as well have been jet fuel. “For the first time in a long time, there’s hope and optimism,” West Virginia Representative Evan Jenkins told the civic center crowd. “Everyone knows it. Everyone can feel it.”

Here in the capital of the state that depends on coal more than any other, the hope of a rebound is understandable. In 2006, burning coal provided 49% of the country’s electricity, but by last year that figure had declined to just 30%, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). Over that same period, annual production in West Virginia declined from 150 million tons to less than 90 million. Much of that is the result of the boom in natural gas, which has become cheap and plentiful thanks to fracking and other new extraction technologies. Last year, for the first time, natural gas unseated coal as the top source of U.S. electricity. Coal also has an environmental problem, accounting for the most carbon emissions of any fossil fuel used for electricity. At the same time, the cost of renewable power sources like wind and solar have become increasingly competitive with coal, further eroding its market share.

Nowhere have these trends hit harder than in West Virginia. More than a century of mining has depleted the state’s most accessible reserves, forcing companies to spend more money to dig deeper into the earth. As demand for coal dwindles, many have decided it’s just not worth it. Between 2011 and 2016, U.S. coal producers lost more than 92% of their market value. The state’s fortunes have stagnated in stride. Today West Virginia ranks 49th in per capita income, 50th in educational attainment and 49th in life expectancy.

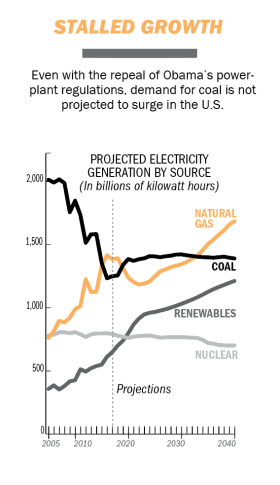

To those who see coal as key to a revival, Trump has been a beacon. On March 28, after promising to gut the Obama-era environmental regulations known in mining states as the “war on coal,” the President made good on his word. Flanked by energy-industry executives and coal miners, Trump signed an Executive Order that is expected to effectively scrap the Clean Power Plan, President Obama’s signature effort to reduce global warming by placing a cap on power-plant emissions. The plan, which had not gone into effect, was expected to force most of the nation’s remaining coal-fired power plants to close and further diminish the country’s appetite for the fuel that helped power its rise. “You know what it says, right?” Trump joked with the miners before signing the order. “You’re going back to work.”

The reality, however, is far more complicated. Undoing Obama’s climate regulations is more like plugging a burst dam than reversing the water’s flow. Without the Clean Power Plan, the EIA expects natural gas and renewable power to account for a combined 57% of the nation’s electricity by 2040. With the plan, those sources were projected to reach 65%. “It’s nonsense. Coal is not coming back,” says Mark Barteau, director of the University of Michigan Energy Institute. “It’s going to continue to lose to cheap natural gas.”

Nor do open mines necessarily mean open jobs. A range of automated technologies, from rock crushers to shovel swings, have taken the place of humans in recent decades—a key reason that employment in the coal industry fell between 1980 and 2010 even as production grew. U.S. coal mining employed 53,000 people last year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 1979, it was more than 250,000.

“There’s almost zero reason to be completely optimistic,” says Ted Boettner, executive director of the West Virginia Center on Budget & Policy. “It’s a disservice to coal-mining communities to tell them they will have a mighty comeback.”

That may not be clear in the White House, but it is in the places that do the mining. In West Virginia, it’s striking that even those who applaud Trump’s repeal of Obama’s environmental agenda are preparing for life after coal—or at least beginning to negotiate the terms. Governor Justice, the towering owner of the Greenbrier resort, with an outsize personality and a fortune built on coal, skipped the February industry conference without explanation. Instead, he sent his chief of staff to deliver a dose of reality: a budget proposal for a slew of new fees, including a potential tax increase on coal companies. “I walked in and was able to look under the sheets and look at where we were,” Justice told TIME of his rationale after seeing the state’s $400 million budget deficit. “It was beyond dismal. We’re in a real mess here.”

Indeed, from the statehouse in Charleston to the well-worn tables at Park Avenue Restaurant in Danville (pop. 688), nearly everyone wants to embrace coal’s latest chance, but they cannot escape the fact that the future is bleak. And what comes next is a subject of animated debate.

The first thing that catches the eye at the Coal Heritage Museum in Madison is a small but striking image of a miner hovering over a city. With his arms rested on his waist, the deity-like miner uses his helmet lantern to illuminate the city.

The message isn’t meant to be subtle. “A lot of miners take pride in it,” says Carl Dunlap, who spent 40 years as a coal miner and now mans the front desk of the museum. “We’d go blind in the dark.”

He’s right. Coal was discovered in West Virginia in 1742, just a few miles from where the museum sits, and it became central to the state’s economy in the 19th century when the Industrial Revolution sent demand soaring. Eventually, all but two of the state’s 55 counties became a source for the black rock. Coal powered the nation through World War II and was critical during the energy crisis in the 1970s, when Middle Eastern sheiks embargoed the sale of oil. Demand peaked in 1988, when coal provided nearly 60% of U.S. electricity.

There were ups and downs in the decades that followed, but in the past 10 years the decline began to resemble a death spiral. West Virginia produces 60% of the coal that it did a decade ago and employs about 12,000 people as coal miners—down from more than 64,000 in the 1970s. The effects extend far beyond the people working directly in the industry. Revenue from a state tax on coal production—a key source of funding for local communities—is expected to decline from more than $420 million in 2012 to $151 million by 2018.

It’s market forces that make this moment the most challenging time in the coal industry’s long history—and a key reason why energy analysts are skeptical of any promise to bring it back. The development of fracking opened up once unreachable reserves of natural gas and has slashed its price by two-thirds since 2008. Wind and solar, once liberal pipe dreams, now compete with coal on price in many places. At the same time, the most accessible—and therefore cheapest—coal reserves in Appalachia are mostly mined out. “Trump is not going to bring all the coal jobs back,” says Jason Bordoff, director of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. “There isn’t a lot of investment activity, because in some cases it looks more economically attractive for firms to invest in cleaner technologies.”

The tune was far different at the West Virginia Coal Association conference, where over the course of two days presenters slammed Obama as a jobs killer, praised Trump as a potential savior and dismissed climate change as a fiction. “This war on coal has come from the environmental community, from the White House and from a host of others,” says Roger Horton, a retired miner who founded the advocacy group Citizens for Coal. “And it’s been strangling our ability to provide these jobs.”

That view crosses party lines in a state filled with billboards telling the EPA to stop killing jobs and bumper stickers suggesting that those who don’t like coal can give up electricity. “The mess started because Obama wanted to kill coal,” says Rupert “Rupie” Phillips, the lone independent in the West Virginia house of delegates. “Thank God for Donald Trump.” Phillips, who has vowed to do everything in his power to prevent any new taxes or regulations on the industry, made clear that his only priority is making the mines hum again. “I have no loyalty when it comes to my coal,” he said at the conference, to raucous applause.

There’s more room for nuance outside of the echo chamber. On a recent night in Boone County, where coal was first discovered in the state, longtime residents were skeptical of a return to the glory days. “It’s moving up a little, but some of these people need to realize they’re not going to make $30 an hour like they used to in a mine,” says Mary Ann McClure over dinner at Park Avenue Restaurant. “It’s just not there like it used to be.”

McClure and her dinner mate JoAnn Harmon both would like to see coal come back—even if they know it’s unlikely—but when we talked, they seemed more interested in what’s happening just a few miles up the road, where the state government has promised to transform the site of a former 12,000-acre surface mine into a commercial development park with offices, retail and, most important, jobs.

Governor Justice says he’s going to make sure the project gets built. Justice is a Democrat, but his political appeal has been likened to that of Trump’s. Both are wealthy businessmen who until now had never held elected office, with little in the way of concrete political ideology. Justice even has a tax controversy of his own: millions of dollars in unpaid fees assessed on his coal mines.

Still, his central promise resonated with voters: “Jobs, jobs, jobs.” And to the extent that he had an economic platform, it emphasized tax cuts and reviving coal. Justice even reopened a few of his company’s mines just days before the election—an apparent down payment for the bright future in store for the industry.

Taking office has a way of bringing a politician back to earth. West Virginia faces a deep budget deficit, thanks in part to the shrinking revenue from the state’s coal tax, and even the most severe regulatory rollback won’t reverse that trend. While Justice is fond of saying that miners have been “overregulated out of a job,” he has come to realize that coal will not be as important to the state’s future as it was to its past. “There’s real hope and real optimism,” Justice says, but “you’re still going to have thousands and thousands of displaced miners.”

The governor’s agenda includes a wide variety of measures to raise revenue and repair the state’s recently downgraded credit rating. He wants legislators to raise the state’s sales tax, create a new business tax and increase the gasoline tax. (They have balked so far.) And he proposed a sliding scale of taxation that would make coal companies pay more when their production increases.

It’s all part of an effort to think beyond the state’s dominant mineral. Justice wants to spend billions of dollars to rebuild roads and increase broadband Internet access—nearly one-third of people in the state can’t get it—in an attempt to make West Virginia more attractive to outside investors. He hopes he can jump-start the timber and furniture-making industries and encourage new businesses to set up shop. There is also hope in West Virginia’s growing tourism industry, which has benefited from privately sponsored environmental-cleanup efforts across the state’s scenic trails, mountains and waterways.

Justice doesn’t refer to his plans as economic transition, a loaded phrase sure to draw even more ire from the coal industry, but it’s clear that that’s exactly what he wants to achieve. The prospect elicits excitement in some quarters and fear in others.

For those still working in the mines, the decline of coal is a direct blow to their ability to provide for themselves and their families. An experienced coal miner can earn $100,000 along with benefits and the promise of a pension. Jobs in the new industries targeted by economic-transition plans—think call centers, shipping warehouses and non-union manufacturing—often pay minimum wage or else require specialized training and a college education.

But in a state where coal has long been an icon as well as a livelihood, the industry’s fade takes a psychic toll. Coal is in the names of West Virginia’s roads and rivers, stamped on its buildings and the source of scholarships at its leading universities. For years, the football teams at Marshall and West Virginia squared off in the Friends of Coal Bowl, and in 2009 the state named coal its official rock. “West Virginia has always relied on coal,” says Tom Southern, who lives near the coal museum in Madison. “That’s been their mainstay. That’s what they do.”

Yet the possibility of a different way of life doesn’t seem to scare all older coal miners. Randy Smith, a longtime miner who was first elected to the state senate as a Republican in 2012, proudly wears a Friends of Coal lapel pin. His office is decorated with memorabilia from decades in the mines, and he says he wants coal jobs to remain a career for those who desire it. But it’s always been a hard life, and he says he’d welcome more options in the state. “I’m a coal miner, been a coal miner all my life. My son, I didn’t want him to be a coal miner. The coal is in my blood, but I want what’s best for my kids,” Smith says. “We have to use this opportunity to diversify our economy. Coal will never be what it was.”