The Poet Who Died For Your Phone

Hundreds of thousands of people travel from China’s countryside to its cities to work in factories, building devices for international consumers and trying to assemble better lives for themselves. Xu Lizhi left behind a haunting record of that life

By Emily Rauhala / Shenzhen and Jieyang

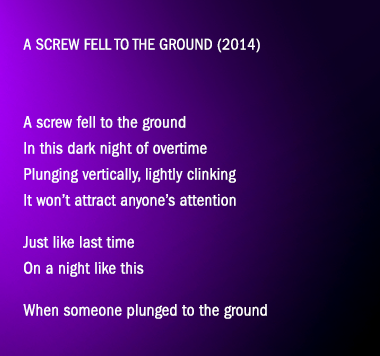

He dreamed about it, wrote about it. He rolled it around in the palm of his hand. Working through the “dark night of overtime” in January 2014, the 23-year-old Xu Lizhi imagined himself like a misplaced screw, “plunging vertically, lightly clinking,” lost to the factory floor. “It won’t attract anyone’s attention,” he wrote. “Just like the last time/ On a night like this/ When someone plunged to the ground.”

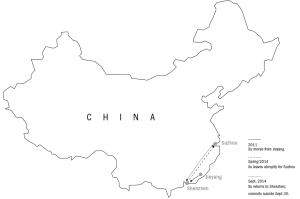

A village boy with clothes-hanger shoulders and a high school education, Xu moved to the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen in 2011. He was looking for a way out of rural life; he hoped to find a way to use his mind. Like hundreds of thousands before him, he settled, to start, for a spot on the assembly line at Foxconn Technology Group, the Taiwan manufacturing giant linked to just about every other name in electronics, from Apple to Acer and Microsoft. To make sense of what he saw there, he started to write, his evocative work earning him a modest following in the city’s small community of dagong shiren, or migrant poets.

In his 3½ years in Shenzhen, Xu captured life there in brutal, beautiful detail. In the city, the country kid found a voice that roared, publishing poems in company newspaper Foxconn People and sharing his work online. Factory workers are often treated as interchangeable, anonymous. To readers, his words were a reminder that every laborer has a mind and heart; for him, writing was a way out. “Writing poems gives me another way of life,” he told a Chinese journalist in an unpublished interview that TIME has seen. “When you’re writing poems, you’re not confined to the real world.” For the first time, Xu’s brother and close friends shared his story with the foreign press.

In the factory city, 2011 was a sad and strange time. The complex known as Longhua is home to some 100,000 workers from across China. In 2010, at least 17 attempted suicide; 14 died. Thanks to confidentiality clauses and tight security, it was hard to know what was happening on the inside. Labor groups blamed working conditions: long hours, modest pay and mindless, repetitive work. The late Steve Jobs, a major customer, called the deaths “troubling” but noted that the suicide rate was lower than the U.S. average. Foxconn countered that conditions were fine. To dissuade jumpers, it hung nets from the dorm — a macabre spectacle that made headlines around the world. “The company places a priority on ensuring the welfare of all of our over one million employees across all of our operations globally,” Foxconn said in a statement to TIME. “… Our record of progress is very clear and the significant enhancements in our company’s working conditions have been confirmed by external audit groups.”

Though consumer activism in the 1990s and 2000s called global attention to sweatshop conditions in Guangdong’s sneaker factories, the lives of China’s migrant laborers have long since faded from view. Outside activist circles, many accepted the notion that young workers were cheerfully trading their youth for a better livelihood. They imagined that they, like the rest of China, were rushing unambivalently toward consumer capitalism, saving their factory wages for ever-newer, shinier phones.

That, of course, was only part of the story. The great economic experiment orchestrated by Mao Zedong’s heirs paved the way for more than 35 years of growth and profound social transformation. Textbooks credit these cadres with “lifting” hundreds of millions out of poverty, but it was ordinary Chinese like Xu who toiled their way to lives that their parents could not have imagined. Now the days of double-digit GDP growth are over, and state-led “socialism with Chinese characteristics“ has spawned one of the most stratified societies on earth. People no longer march in unison — some jump forward, others fall back.

In the years Xu spent in Shenzhen, several more migrants jumped to their death. Xu himself never made the leap to the life he imagined — to a desk job, a chance to think, and the means to make his family proud. He stopped believing that people were listening. That things could change. On Sept. 30, 2014, eight months after he imagined himself plunging, Xu Lizhi stepped off the ledge.

Chasing Fortune

When Xu left his village outside the city of Jieyang he tread a well-worn path. The people of eastern Guangdong province have been on the move for centuries, sailing south to find work in the trading ports of Southeast Asia, or slipping across the border to try their luck in Hong Kong. The area, known as Chaoshan, is famous in China as the birthplace of businesspeople.

By the time Xu was born, in July 1990, Chaoshan’s strivers were moving west, to the Pearl River Delta, where a great economic experiment was under way. A former fishing village, Shenzhen, was morphing into a manufacturing hub and there was money to be made. Most of the work was brutal and poorly paid, but some struck it rich. “In our village, people dropped out early to go to the city,” said Xu Hongzhi, Xu Lizhi’s oldest brother, over dinner in Jieyang. “All anyone could talk about at the spring festival was who would make it big next year.”

Xu Lizhi seemed destined to join the great migration. He was the youngest of three sons born to parents that farmed rice, leeks and taro on a modest plot. His oldest brother remembers him as shy kid unsuited to farm work, a boy who loved reading but had limited access to books. (There was no library or bookstore; his parents did not read.) In high school, when he should have been cramming, he was busy watching TV talent shows, Xu Hongzhi says. Xu Lizhi’s favorite, an extravaganza called Super Boy, plucked ordinary people from obscurity and made them stars.

Xu Lizhi hoped to shine a little brighter by getting into university, but his scores on the national entrance exam fell short, a failure that haunted him, according to his brother and two friends. His family urged him forward: in their village, marrying off a son meant buying a home — they needed to save for three. Xu Hongzhi told his little brother to forget about the exam and follow his classmates to the city. “I said to him, ‘What’s in the past is in the past, work hard and you can still change your fate.’”

And until the end, the family believed he would.

Bright Lights, Big City

For a curious young man, Shenzhen has much to offer. The city of 7 million pulses with people from every place and province (and no shortage of bookstores). In the 2013 “I Speak of Blood,” Xu Lizhi captured the teeming cosmopolitanism of his adopted home, observing from his “matchbox” room a mix of: “Stray women in long-distance marriages/ Sichuan chaps selling mala soup/ Old ladies from Henan running stands/ And me with my eyes open all night to write a poem/ After running about all day to make a living.”

Making a living was an almost all-consuming task, an act of endurance that wore at his body and tore at his mind. At his first factory job at Foxconn, Xu alternated each month between day and night shifts, spending long, restless hours on his feet. Though he told a friend he got used to the pain, his poems ache with anguish. “By the assembly line I stood straight like iron, hands like flight,” he wrote in August 2011. “How many days, how many nights/ Did I — just like that — standing, fall asleep?”

Factory life made Xu feel like a machine, a half-human with a “stomach forged of iron/ full of thick acid, sulfuric and nitric.” The same jig that forced workers’ “skin to peel” replaced their human tissue with a “layer of aluminum alloy.” He felt dehumanized, stunted, as if the work itself was stealing his ability to conjure language beyond “working words” like “workshop, assembly line, machine, work card, overtime, wages …”

The world of words was his only respite. On his rare days off, Xu liked to visit bookstores, lingering in the aisles, friends say. He also frequented the factory library, and met writers and editors involved in the company newspaper and started writing poems and reviews for it. “I was very excited when I first saw his work,” says an editor familiar with his early work who asked to remain anonymous to protect his job. “It made my eyes widen.”

Xu started publishing poems online and submitting his work to small magazines. He also connected with fellow worker-poets in the Pearl River Delta, both in person and online. One Sunday in the spring of 2012, he took the bus to the neighboring city of Guangzhou to attend a gathering. A fellow writer, Gao, noticed a thin young man sitting on the sidelines, listening while staring at his phone. Gao asked him to join the group. Reluctantly, he did.

Afterward, Gao walked Xu to the station. While they waited for the Shenzhen-bound bus, they shared a meal and a drink. They were both 20-something migrants in jobs they despised, sensitive men in a city that rewarded the brash. Xu told Gao he felt trapped, unhappy with his job but unable to secure another. “Lizhi knew he should be using a pen and not a hammer,” Gao says. “But there was a gap between reality and his dreams.”

Eating Bitterness

By 2013, Xu felt like the city might swallow him. He traded the factory dorm for a small, rented room, but the space started to feel like a coffin. Some days, he longed to write like the Tang dynasty greats, soaking his words in wine and beauty, musing about the play of “the moon on snow.” Sleepless, stifled, he could not. “This reality,” he wrote, “only lets me speak of blood.”

Xu managed to switch from the assembly line to the logistics department, a job that gave him a bit more variety and the occasional chance to play on his phone, he told friends. But the new job did little to quell his anxiety, and death began to haunt his work. In “A Kind of Prophecy” he compared himself to his grandfather, a thin man who “swallowed his feelings” and died young. “In the autumn of 1943, the Japanese devils invaded/ and burned my grandfather alive/ at the age of 23/ This year I turn 23.”

Xu said nothing of his struggle to his family, and little to his friends. When he phoned home, he only shared good news, his oldest brother Xu Hongzhi says. His family had no idea he wrote. Xu Lizhi told a Chinese journalist he was certain they would not understand. “On one hand, they cannot understand poetry,” Xu said. “On the other I sometimes mention unpleasant experience, and I don’t want them to worry.”

The people around him believed a certain amount of suffering was normal, even necessary. Ask a veteran of Shenzhen’s factories about their early years, and, odds are, they will speak with pride about “eating bitterness,” a Chinese phrase that suggests an ability to endure. Born to parents who knew famine, earlier migrants moved from abject poverty on the farm to deadly sweatshops in the city. Those who survived have a tendency to see new arrivals as lacking resolve: a kids-these-days thing.

Xu Hongzhi and the editor who asked not to be named, had both, like millions before them, moved to the city as teenagers, toiled in tough conditions, and come out stronger. They believed Xu Lizhi would do the same if he just waited and worked. When he looked at Xu, the editor saw talent, not despair. “Things today are so much better than they used to be,” he says. “But I guess today’s generation has different needs and expectations.”

Xu alternated between hope and hopelessness. He dared to hope for respite from monotony and a chance to use his talent, and twice summoned the courage to apply, unsuccessfully, for desk jobs — as a librarian at the factory, and at his favorite Shenzhen bookstore Youyi. But when a local journalist asked him about his future, he said he could not expect too much: “We all hope our lives will become better and better, but most of us don’t control our destiny.”

Epilogue

As spring festival approached in 2014, Xu left his job at Foxconn without telling his family, his brother said. He told friends he was off to the city of Suzhou not far from Shanghai to see a girl and start afresh. It is unclear where he spent that spring and summer; he lost touch with several close friends, but paid his Shenzhen rent, his brother says.

In late September he re-emerged in Shenzhen and signed a new contract with Foxconn. Two days later, on the eve of China’s Oct. 1 National Day holiday, Xu Lizhi, by then 24, walked to a mall across from his favorite bookstore, took the elevator to the 17th floor, and jumped to his death. It was not until the news of another suicide broke that friends found his final poems and a post scheduled to publish on Oct.1: “A new day,” it read.

In the wake of his death, labor groups translated Xu’s work into English, leading to notices in Bloomberg News and the Washington Post. Chinese poet Qin Xiaoyu is making a documentary film about Xu’s life and work. He also published a slim volume of his poems. Foxconn, citing company policy, declined to answer specific questions about Xu.

Xu Hongzhi took the long-distance bus from Jieyang to negotiate a settlement with the company. Unable to take Xu Lizhi back to the village, he carried his brother’s ashes to the coast and scattered them in the sea. Zhou Qizao, a fellow worker-poet, penned a defiant tribute: “Another screw comes loose/ Another migrant worker brother jumps/ You die in place of me/ And I keep writing in place of you.”

— With reporting by Gu Yongqiang

If you or a loved one has suicidal thoughts, call 1-800-273-8255 or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.