Boko Haram’s Other Victims

Nigeria struggles to absorb thousands more traumatized children now returning from brutal captivity

By Aryn Baker/Maiduguri |Photographs by PAOLO PELLEGRIN—MAGNUM for TIME

Boko Haram kept Fatsuma’s daughter Fatima for a year and a half before she escaped. Now that she has been reunited with her family in a camp for people displaced by Nigeria’s war to defeat the Islamist insurgency, her mother says she doesn’t trust her.

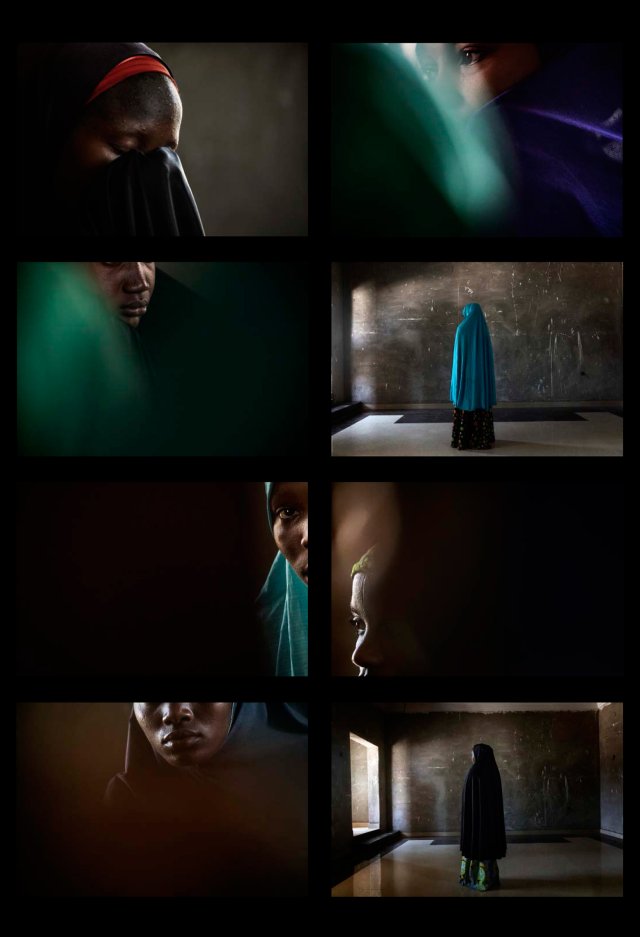

Dada, 14, with her daughter Hussainia, 18 months, was kidnapped and raped at age 12 while a captive of Boko Haram.

Dada, 14, with her daughter Hussainia, 18 months, was kidnapped and raped at age 12 while a captive of Boko Haram.

The 14-year-old retreats into silence for days, only to lash out explosively at the slightest disturbance. “We are afraid of her sometimes,” says Fatsuma, with an uneasy glance at her daughter sitting across the room. “When she came back from Boko Haram, she was different, hard-hearted.”

Fatsuma believes it was because Fatima was forced to watch as Boko Haram fighters killed her brother in front of her, and was threatened when she cried. Fatsuma hasn’t seen her daughter cry since, but Fatima often wakes up the family in the middle of the night with her screaming. Most unnerving of all, Fatima soothes herself by chanting Boko Haram dirges. “I love her,” says Fatsuma. “I am happy she is with me now, but Boko Haram still has a part of her.”

With no formal database for the missing, it’s impossible to know how many children like Fatima have escaped Boko Haram captivity since the militants began their scorched-earth campaign to take over northeastern Nigeria in 2009. Humanitarian organizations estimate that there are anywhere from thousands to tens of thousands of victims who are suffering both the physical and the psychological trauma of abduction, indoctrination and savage mistreatment: children as young as 3 being snatched from their beds and thrown into sacks, 6-year-olds made to watch their parents die and teenagers forced to fight in a war they don’t even understand.

The world’s attention, however, has been focused on just 276 of those victims: the young women whose fate became a global concern after they were kidnapped from their boarding-school dormitory in Chibok on the night of April 14, 2014. The Nigerian activist group Bring Back Our Girls sprang up in the wake of the kidnapping, drawing international attention to their plight with celebrity-studded hashtag advocacy. Even Michelle Obama joined in with a Twitter selfie sporting the group’s message. On May 6, after three years in captivity, 82 of the young women were released—the latest and largest group of abductees to be freed—in exchange for five Boko Haram commanders.

In Banki, a once prosperous trading town that was all but destroyed by Boko Haram in 2014, the overwhelmed nurses at the local clinic are on the front line of the efforts to help brutalized young victims return to a normal childhood. Since the town’s liberation two years ago, the nurses have patched up teenagers conscripted at gunpoint into the rebel army, tended to starving captives fleeing the insurgents’ redoubt in nearby Sambisa Forest and delivered the babies of girls who were forcibly married to older fighters. So when government officials commissioned the nurses to do a primary health assessment on these newly freed young women, who had been released at a location nearby, they prepared for the worst. Instead, the young women were healthy, well dressed and remarkably calm. “We expected to see them suffering,” says Maryam Abdulkadir, an earnest and fashionable young woman who completed her nurses’ training only a few months before being sent to Banki from the state capital, Maiduguri. “Usually when girls come from Boko Haram, they are wearing rags and are emaciated. These girls didn’t look like they had spent the past three years in the forest.”

Women and children at a camp for internally displaced persons in Dikwa, Nigeria.

Women and children at a camp for internally displaced persons in Dikwa, Nigeria.

The Dalori 1 camp outside Maiduguri is home to 29,000 people who were forced to flee Boko Haram attacks.

The Dalori 1 camp outside Maiduguri is home to 29,000 people who were forced to flee Boko Haram attacks.

And unlike most Boko Haram victims passing through the busy clinic’s door into the dusty chaos of a sprawling camp for tens of thousands of people fleeing the fighting, the young women were taken to the Nigerian capital, Abuja, where they were placed in a specially designed residential facility to help them recover from their ordeal. Over the next nine months they will be provided health services, psychological counseling, trauma therapy and remedial-education courses to help them catch up on their lost schooling—similar to the rehabilitation program previously set up for 21 Chibok girls who were released in October.

Their recovery will not be easy. But for every young woman who is whisked into a comprehensive reintegration program, thousands more traumatized Boko Haram abductees have been thrust, untreated, into communities that are not equipped to tend to their wounds. Parents have been reunited with children who were beaten, starved and forced to participate in ritualized massacres. Some converted. Others fought for the insurgents. Many were raped. Fatima still has nightmares about the time she was forced, along with several other captive girls, to stone a couple to death for the sin of committing adultery. “I didn’t want to do it. But if we didn’t throw the stone, they said they would kill us,” she says. “If you shed a tear, they will beat you with the side of their guns.”

Mohammed was orphaned when his parents were killed by Boko Haram; he is thought to be about 5 years old.

Mohammed was orphaned when his parents were killed by Boko Haram; he is thought to be about 5 years old.

After six years and more than 20,000 dead, Boko Haram’s vicious campaign to carve a caliphate out of northeastern Nigeria is slowly coming to a close. Founded in Maiduguri in 2002 by a charismatic preacher who advocated a fundamentalist interpretation of the Quran, Boko Haram evolved into a full-fledged insurgency in 2009, eventually taking control of an area greater than the size of Belgium. But the group, under assault by a multinational force, started to lose territory and strength in 2016.

Now the government is working to stabilize the region and ensure that the 2 million people displaced by the fighting can return home and start their lives over again. But for those kidnapped by Boko Haram, home is not always a refuge. Their communities may brand them as sympathizers or reject them out of fear that their time in captivity has led to Manchurian Candidate–style indoctrination. Friends, neighbors and even family members may deride them as annoba—epidemics—a term also used to describe the deadly Ebola virus, which can infect anyone who comes too close to its victims. Without treatment, the abductees may not be able to reintegrate into society. And without understanding what they have been through, the communities may never be able to accept them, leaving an open wound to fester as Nigeria seeks to bring this brutal chapter of its history to a close.

Fatima, 14, escaped from Boko Haram; she now lives in a camp in Maiduguri for people fleeing the war.

Fatima, 14, escaped from Boko Haram; she now lives in a camp in Maiduguri for people fleeing the war.

During the height of the insurgency, in 2015, Fatima Akilu, a forensic psychologist and specialist in preventing and countering violent extremism, was brought in to assess the needs of some 230 children who had just been released from Boko Haram captivity. “When we walked in, there was not a single sound,” she says. The eerie quiet continued for several days as the psychologists attempted to engage with the former captives. Eventually, they brought in toys. At that point, says Akilu, the only sound they heard was one of destruction. “They tore the heads off the dolls. They were stamping on the toy cars,” she says. After weeks of therapy, the psychologists understood that during captivity, Boko Haram fighters beat the children anytime they made a sound. They taught the children that playing with toys was wrong and hit them when they were caught doing so.

Awal and Ibrahim, both 13, fled Boko Haram and are now reunited with their mother at a camp in Maiduguri.

Awal and Ibrahim, both 13, fled Boko Haram and are now reunited with their mother at a camp in Maiduguri.

The military screened Fatima, 17, to assess whether she had been indoctrinated by Boko Haram. Thousands of abductees have been thrust, untreated, into communities that are not equipped to tend to their wounds. Parents have been reunited with children who were beaten, starved and forced to participate in ritualized massacres. Some converted. Others fought for the insurgents. Many were raped.

The military screened Fatima, 17, to assess whether she had been indoctrinated by Boko Haram. Thousands of abductees have been thrust, untreated, into communities that are not equipped to tend to their wounds. Parents have been reunited with children who were beaten, starved and forced to participate in ritualized massacres. Some converted. Others fought for the insurgents. Many were raped.

All of Boko Haram’s abductees were forced to learn the Quran by rote, says Umaru, a lanky 12-year-old from Gwoza who was held by the militants for more than two years. He is wearing a tattered yellow T-shirt and fidgets with a green plastic horse as he sits on the floor of an empty classroom in the Bakassi camp for the displaced, just outside Maiduguri. If the children made a mistake in pronunciation, they would be beaten. When the boys weren’t at Quranic lessons, they worked as spies or ammunition couriers. The girls collected water and firewood and did the washing.

Everyone had to attend the daily justice sessions, in which the commanders meted out brutal forms of punishment for various infractions, from theft and blasphemy to adultery and insubordination. Most days, Umaru witnessed five or six executions. “They would gather everyone, make us watch,” says Umaru. “They would tell them to lie down. They would tell the public this is what they did. Then they shot them.” In Banki, where tens of thousands of people fleeing Boko Haram’s predations in the nearby forest created temporary homes, 6-year-old Yakura recalls that the fighters who kidnapped her used big knives for their public executions. Wearing a ragged lace dress that looks as if it was once a party frock, Yakura says she still hopes to find her family. She was only 4 when she was kidnapped, and she says she can’t block the image of the executions from her mind.

Boko Haram abducted the entire village of Mafa, including Fatima, 21, who escaped after nearly a year in captivity.

Boko Haram abducted the entire village of Mafa, including Fatima, 21, who escaped after nearly a year in captivity.

“They cut off a man’s head and threw it away from his body,” she says. “They said it was to warn the others to behave.” That exposure to violence worries psychologist Akilu. Children who become desensitized to violence are more likely to commit it. “They are ticking time bombs. A lot of these children think that the easiest way to solve even the smallest conflict is by a violent act.” She notes that Boko Haram fighters often force children to kill their parents if they are suspected of supporting the government. “A child who can kill his parent can do anything.”

Many of the boys abducted by Boko Haram are conscripted into the ranks of fighters, says Geoffrey Ijumba, head of the UNICEF field office in Maiduguri. They are conditioned to embrace the group’s beliefs and forced to attack their own towns and people. Young women are also turned into weapons, either against their will or by indoctrination. Fatima G., who was held by Boko Haram along with Fatsuma’s daughter of the same name, is still haunted by the memories of friends in captivity who became suicide bombers for the militants.

The fighters often approached the young women with treats and stories of a glorious martyrdom. Some of her friends, says Fatima G., seemed to be on some kind of drug. The militants gave the young women bombs to put under their headscarves or around their waists. Fatima G., then 13, would know their fates only when she heard about a suicide attack and saw her captors celebrating. Outwardly, she pretended to join in the celebration. But each time, she says, she gave a silent prayer for God to help the bombers and their victims. She says at least 15 of her friends died that way.

Nurses from the Banki clinic relate that according to the 82 newly freed young women, 11 of their fellow students became suicide bombers. It is impossible to verify, says Aisha Yesufu, a co-founder of Bring Back Our Girls. On the evening of June 25, six female suicide bombers attacked multiple targets in Maiduguri, killing 15, including themselves.

Boko Haram has used at least 117 children in suicide bomb attacks since 2014, according to UNICEF. More than 80% were girls, some as young as 7. Girls and young women make better bombers because society sees them as harmless, so they are rarely stopped at security checkpoints. They are also easier to manipulate, says Fatima G. She might have befallen the same fate if her mother had not been abducted alongside her. “My mother is the one who kept me safe,” she says. “Many times the preachers came to us, to tell us to go for suicide bombings, but whenever my mother saw them coming, she shouted at them and they left.” Her mother also kept her from being forcibly married or raped, an all-too-common fate for female captives.

When the 82 young women arrived at the clinic, the nurses were surprised to see that none of them were carrying babies, especially since the previous 21 Chibok girls came out of captivity with four. In the nurses’ experience, most female captives had been forcibly married to fighters, a meaningless designation meant to give religious sanction to repeated rape.

After six years and more than 20,000 dead, Boko Haram’s vicious campaign to carve a caliphate out of northeastern Nigeria is slowly coming to a close leaving thousands displaced and traumatized.

After six years and more than 20,000 dead, Boko Haram’s vicious campaign to carve a caliphate out of northeastern Nigeria is slowly coming to a close leaving thousands displaced and traumatized.

Women suspected of being raped by or married, willingly or not, to Boko Haram fighters are derisively known as “Boko wives” and rejected by their communities for sleeping with the enemy. The stigma and suspicion can follow a young woman for years, preventing her from going to school, getting married or even opening a business in a small village, where secrets are impossible to keep. Dada was 11 years old when she was kidnapped from Banki three years ago. She hadn’t even started menstruating when she was shoved before a circle of fighters with a man she had never met. After a few prayers, she was told she was married and sent to his hut. “I started thinking, How can they marry me? I am too young,” she says. A few months later, she was pregnant. “I never knew what pregnancy was. Just that my belly was growing bigger.”

Dada escaped when she was 8 months pregnant. She gave birth on the run and eventually reunited with her mother and sister in Maiduguri, where they share a one-room shack behind a busy roadside market. With her full cheeks, upturned nose and wide eyes, Dada doesn’t look much older than her daughter, 18-month-old Hussainia, whom she cradles in her lap.

Dada tenderly plaits Hussainia’s bushy hair into neat cornrows. Going back to Banki is out of the question, says Dada. It wouldn’t be safe for her daughter. She worries that her neighbors will say Hussainia has “bad blood” because her father was a Boko Haram fighter. “A lot of people think those children are bad and dangerous and wicked,” she says. She has heard stories, backed up by UNICEF, of similar children being killed by the community and sometimes even family members.

Dada once dreamed of becoming a schoolteacher in her village. That future is closed, she says. “It used to make me angry when I thought about how he destroyed my life for getting me pregnant,” Dada says. “It makes me sick and it turns my head around, and I feel like collapsing.” The only thing she can do now, she says, is ensure that Hussainia gets to go to school.

Displaced people in Banki, a once prosperous trading town that was all but destroyed by Boko Haram in 2014.

Displaced people in Banki, a once prosperous trading town that was all but destroyed by Boko Haram in 2014.

“My daughter will have what I could not.” She has no intention of ever telling Hussainia who her father was. If her daughter asks, she plans to tell her that he died in the fighting.

In a small group-therapy session on the other side of Maiduguri, psychologist Terna Abege sits among a circle of eight women who are draped in brightly colored headscarves. He is teaching them a technique to stop the paralyzing flashbacks of explosions and killings that derail their lives—telltale signs of posttraumatic stress disorder. He instructs the women to put out their right hands in a stop gesture and recite the word tsaya, or stop. “We understand you have gone through a horrible experience because of Boko Haram,” he tells the group. “Before you feel anger, before you cry, say, ‘Tsaya.’” The group puts out their hands and repeats after him in unison. They smile uncertainly at first but slowly gain confidence, until they are all combatting their own personal demons in a cacophonous chorus.

Abege calls the method a “thought stopper.” It is part of a suite of therapies he is using to help victims of Boko Haram get on with their lives. He is one of four staff psychologists working with the Neem Foundation, an organization co-founded by Akilu in 2016 to offer psychological counseling for Boko Haram victims. The foundation works with specially trained counselors to conduct a dozen such group-therapy sessions a week. They are time-consuming and staff-intensive, but they are the only real way to combat trauma, says Abege. Many of the camps for the displaced offer specially designated safe spaces for therapeutic activities such as art classes and vocational training.

Humanitarian organizations estimate that there are anywhere from thousands to tens of thousands of victims in Northern Nigeria who are suffering both the physical and the psychological trauma of abduction, indoctrination and savage mistreatment by Boko Haram.

Humanitarian organizations estimate that there are anywhere from thousands to tens of thousands of victims in Northern Nigeria who are suffering both the physical and the psychological trauma of abduction, indoctrination and savage mistreatment by Boko Haram.

More than 2 million people have fled from Boko Haram; some 700,000 live in makeshift camps near Maiduguri, where water is scarce.

More than 2 million people have fled from Boko Haram; some 700,000 live in makeshift camps near Maiduguri, where water is scarce.

They are vital resources, says Abege, but they are not enough and are akin to offering aspirin to combat cancer. “If we don’t treat the trauma now, most of them will sooner or later see high cases of mental illness. Without help, they face a bleak future—depression, drug use, social crimes—where the only thing to do is to hit back at the government that fails them.”

Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, where the insurgency hit hardest, has a ratio of 1 psychologist for every 375,000 residents. Abege estimates that given the level of need he has seen, the ideal ratio would be closer to 1 for every 4,000. There aren’t enough trained psychologists in all of Nigeria to answer that need. Abege and Akilu at the Neem Foundation are attempting to fill the gap by training lay counselors and religious leaders who can at least conduct group-therapy sessions.

But what the country really needs, says Abege, is government commitment. He wants to see more universities offering psychology degrees. Already the University of Maiduguri has opened 600 spots for psychology students, and the Neem Foundation now offers a nine-month course in trauma counseling. But once those students graduate, they need to be compensated as public-health personnel and not treated as luxuries for the private market. “The efforts the government puts into combatting Boko Haram, the same amount should be spent meeting the needs of the people who are their victims,” says Abege.

To many in northeastern Nigeria who are suffering from the effects of the insurgency, the Chibok girls have become an unfortunate example of how celebrity—no matter how unwanted—skews attention and funding. Yesufu of Bring Back Our Girls notes that the organization has always said that the Chibok girls are a symbol of every young woman who has ever been kidnapped by Boko Haram. The government says the same. But that is little comfort to Fatsuma, who despairs of ever seeing her daughter escape from her living nightmare. “She tells me that there is no death that she hasn’t been through, and she relives it every night,” says Fatsuma as Fatima pulls at the threads of her fraying headscarf.

If Fatima is ever to recover, she will need long-term help, says Ijumba of UNICEF. It’s not enough that the Chibok girls serve as a symbol; their multipronged therapy should set the example for how all of Boko Haram’s victims should be treated. “Even if they release all the Chibok girls, we don’t want the world to think that it is over and pop out the champagne,” says Ijumba. “If nothing adequate is done to help this generation of children, very soon we will have a bigger problem than the one we have now.”

—June 27, 2017