It’s been 15 years since the global effort to ban conflict diamonds began. But the industry is still tainted by conflict and misery

ax Rodriguez knows exactly how he is going to propose marriage to his long-term boyfriend, Michael Loper. He has booked a romantic bed-and-breakfast. He has found, using Google Earth, a secluded garden where he plans to take Loper for a sunset walk. The only thing that troubles him is the issue of the ring. Rodriguez has heard about how diamonds fuel distant conflicts, about the miserable conditions of the miners who wrest the stones from the earth, and he worries. The 34-year-old slips on a gold signet-style ring in the 12th-floor showroom of Vale Jewelry in New York City’s diamond district. “I don’t want a symbol of our union to also be associated with chaos and controversy and pain,” says Rodriguez.

ax Rodriguez knows exactly how he is going to propose marriage to his long-term boyfriend, Michael Loper. He has booked a romantic bed-and-breakfast. He has found, using Google Earth, a secluded garden where he plans to take Loper for a sunset walk. The only thing that troubles him is the issue of the ring. Rodriguez has heard about how diamonds fuel distant conflicts, about the miserable conditions of the miners who wrest the stones from the earth, and he worries. The 34-year-old slips on a gold signet-style ring in the 12th-floor showroom of Vale Jewelry in New York City’s diamond district. “I don’t want a symbol of our union to also be associated with chaos and controversy and pain,” says Rodriguez.

To Mbuyi Mwanza, a 15-year-old who spends his days shoveling and sifting gravel in small artisanal mines in southwest Democratic Republic of Congo, diamonds symbolize something much more immediate: the opportunity to eat. Mining work is grueling, and he is plagued by backaches, but that is nothing compared with the pain of seeing his family go hungry. His father is blind; his mother abandoned them several years ago. It’s been three months since Mwanza last found a diamond, and his debts—for food, for medicine for his father—are piling up. A large stone, maybe a carat, could earn him $100, he says, enough to let him dream about going back to school, after dropping out at 12 to go to the mines—the only work available in his small village. He knows of at least a dozen other boys from his community who have been forced to work in the mines to survive.

Mwanza’s mine, a ruddy gash on the banks of a small stream whose waters will eventually reach the Congo River, is at the center of one of the world’s most important sources of gem-quality diamonds. Yet the provincial capital, Tshikapa, betrays nothing of the wealth that lies beneath the ground. None of the roads are paved, not even the airport runway. Hundreds of miners die every year in tunnel collapses that are seldom reported because they happen so often. Teachers at government schools demand payment from students to supplement their meager salaries. Many parents choose to send their teenagers to the mines instead. “We do this work so we can find something that will let us eat,” says Mwanza. “When I find a stone, I eat. There is no money left for school.”

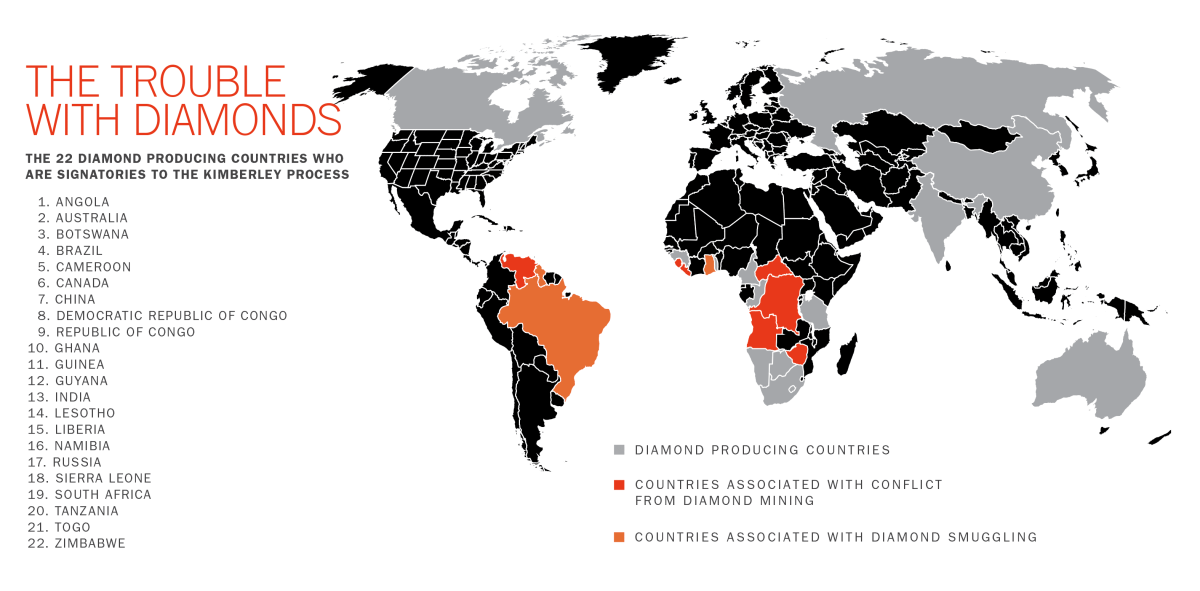

Mwanza and Rodriguez are on opposite ends of an $81.4 billion-a-year industry that links the mines of Africa, home to 65% of the world’s diamonds, with the sparkling salesrooms of high-end jewelry retailers around the world. It is an industry that was supposed to be cleaned up, after the turn-of-the-millennium notoriety surrounding so-called blood or conflict diamonds—precious stones mined in African war zones, often by forced labor, and used to fund armed rebel movements. In 2003 the diamond industry established the Kimberley Process, an international certification system designed to reassure consumers that the diamonds they bought were conflict-free. But more than 10 years later, while the process did reduce the number of conflict diamonds on the market, it remains riddled with loopholes, unable to stop many diamonds mined in war zones or under other egregious circumstances from being sold in international markets. And as Mwanza’s life demonstrates, diamond mining even outside a conflict area can be brutal work, performed by low-paid, sometimes school-age miners. “It’s a scandal,” says Zacharie Mamba, head of Tshikapa’s mining division. “We have so much wealth, yet we stay so poor. I can understand why you Americans say you don’t want to buy our diamonds. Instead of blessings, our diamonds bring us nothing but misfortune.”

Given the ugly realities of the diamond business, it would be tempting to forgo buying a diamond altogether, or to choose, as Rodriguez eventually did, to purchase a synthetic alternative. But Congolese mining officials say diamonds are a vital source of income—if not the only source—for an estimated 1 million small-scale, or artisanal, miners in Congo who dig by hand for the crystals that will one day adorn the engagement ring of a bride- or groom-to-be. “If people stop buying our diamonds, we won’t be able to eat,” says Mwanza. “We still won’t be able to go to school. How does that help us?”

In an age of supply-chain transparency, when a $4 latte can come with an explanation of where the coffee was grown and how, even luxury goods like diamonds are under pressure to prove that they can be sustainable. The Kimberley Process has gone some of the way, yet a truly fair-trade system would not only ban diamonds mined in conflict areas but also allow conscientious consumers to buy diamonds that could improve the working and living conditions of artisanal miners like Mwanza. But the hard truth is that years after the term blood diamond breached the public consciousness, there is almost no way to know for sure that you’re buying a diamond without blood on it.

he Kimberley Process grew out of a 2000 meeting in Kimberley, South Africa, when the world’s major diamond producers and buyers met to address growing concerns, and the threat of a consumer boycott, over the sale of rough, uncut diamonds to fund the brutal civil wars of Angola and Sierra Leone—inspiration for the 2006 film Blood Diamond. By 2003, 52 governments, as well as international advocacy groups, had ratified the scheme, establishing a system of diamond “passports” issued from the country of origin that would accompany every shipment of rough diamonds around the world. Countries that could not prove that their diamonds were conflict-free could be suspended from the international diamond trade.

he Kimberley Process grew out of a 2000 meeting in Kimberley, South Africa, when the world’s major diamond producers and buyers met to address growing concerns, and the threat of a consumer boycott, over the sale of rough, uncut diamonds to fund the brutal civil wars of Angola and Sierra Leone—inspiration for the 2006 film Blood Diamond. By 2003, 52 governments, as well as international advocacy groups, had ratified the scheme, establishing a system of diamond “passports” issued from the country of origin that would accompany every shipment of rough diamonds around the world. Countries that could not prove that their diamonds were conflict-free could be suspended from the international diamond trade.

The Kimberley Process was hailed as a major step toward ending diamond-fueled conflict. Ian Smillie, one of the early architects of the process and an authority on conflict diamonds, estimates that only 5% to 10% of the world’s diamonds are traded illegally now compared with 25% before 2003, a huge boon for producing nations that have a better chance at earning an income off their natural resources.

But Smillie and other critics argue that the Kimberley Process doesn’t go far enough. Unfair labor practices and human-rights abuses don’t disqualify diamonds under the protocol, while the definition of conflict is so narrow as to exclude many instances of what consumers would, using common sense, think of as a conflict diamond. Conflict diamonds under the Kimberley Process are defined as gemstones sold to fund a rebel movement attempting to overthrow the state—and only that. So when, in 2008, the Zimbabwean army seized a major diamond deposit in eastern Zimbabwe and massacred more than 200 miners, it was not considered a breach of the Kimberley Process protocols. “Thousands had been killed, raped, injured and enslaved in Zimbabwe, and the Kimberley Process had no way to call those conflict diamonds because there were no rebels,” says Smillie.

Even in some cases where the Kimberley Process has implemented a ban—as in the Central African Republic (CAR), where diamonds have helped fund a genocidal war that has killed thousands since 2013—conflict diamonds are still leaking out. A U.N. panel of experts estimates that 140,000 carats of diamonds—with a retail value of $24 million—have been smuggled out of the country since it was suspended in May 2013. The Enough Project, an organization dedicated to ending resource-based violence in Africa, estimated in a June report that armed groups raise $3.87 million to $5.8 million a year through the taxation of and illicit trade in diamonds.

Many of those diamonds are likely being smuggled across the border to Congo, where they are given Kimberley Process certificates before being traded internationally. “The Central African Republic is a classic case of blood diamonds, exactly what the Kimberley Process was intended to address,” says Michael Gibb of Global Witness, a U.K.-based NGO that advocates for the responsible use of natural resources. “The fact that CAR diamonds are making it to international markets is a clear demonstration that the Kimberley Process on its own is not going to be able to deal with this kind of problem.” (Representatives of the Congolese body in charge of issuing Kimberley Process certificates deny that CAR diamonds are being laundered through Congo, but mining-ministry officials admit that it is all but impossible to police the country’s 1,085-mile [1,746 km] border with the Central African Republic.)

Many countries, industry leaders and international organizations—including the U.S.-based World Diamond Council, the major industry trade group—have lobbied to expand the Kimberley Process definition of conflict diamonds to include issues of environmental impact, human-rights abuses and fair labor practices. They’ve made little progress. (One reason: any changes to the criteria must be made by consensus. Many countries, including Russia, China and Zimbabwe, have resisted inserting human-rights language that might threaten national interests.) They are instead taking it upon themselves to ensure the integrity of the diamond supply chain and assuage consumer doubts.

Tiffany & Co., Signet and De Beers’ Forevermark brand have instituted strict sourcing policies for their diamonds that address many of these concerns. In New York next March, jewelry-industry executives from around the world will meet for an unprecedented 2½-day conference on responsible sourcing in an attempt to hammer out an industry-wide process as transparent as the one that brings fair-trade coffee to Starbucks. “Why shouldn’t we be able to trace a much more valuable and more emotionally laden product?” asks Beth Gerstein, who in 2005 co-founded Brilliant Earth, one of the first jewelry companies to make responsible sourcing a selling point.

Ava Bai, one of the twin-sibling designers behind New York’s Vale Jewelry, believes the desire of millennials to shop according to their ethics has also helped pushed the industry to embrace sustainability. Fine-jewelry sales in the U.S.—the world’s biggest retail diamond market—have stagnated, growing only 1.9% from 2004 to 2013, even as other luxury items, like fine wines and electronics, have gone up by more than 10%. “Millennial consumers are looking for more than the 4Cs [the classic Cut, Carat, Clarity and Color],” says Linnette Gould, head of media relations for De Beers, which launched its Forevermark diamond brand in the U.S. in 2011 with a commitment to responsible sourcing. “They want a guarantee that it is ethical. They want to know about environmental impact. They want to know about labor practices. They want to know that the communities have benefited from the diamonds they are mining.” For its part, Vale deals directly with one family that does the buying, cutting and polishing. Their buyer sources diamonds from South African and Indian mines—generally considered more sustainable—and the Bai twins plan to visit the South African mine next year.

That kind of supply-chain management takes significant effort and trust, because even experts can’t tell the origins of a diamond simply by looking at it. An experienced gemologist might be able to tell the difference between a handful of rough diamonds from an industrial South African pit mine and those from a Congolese alluvial mine like the one where Mwanza labors. But those differences disappear as a diamond moves up the value chain. “Despite the concern from the public and within the industry about these so-called illicit diamonds and conflict diamonds, there is no scientific or technical way to tell where diamonds came from once they are cut,” says Wuyi Wang, director of research and development at the Gemological Institute of America. Laundering a conflict diamond from a place like the Central African Republic is as simple as cutting it. “That is why traceability from the mines is critical,” says Wang.

ut the idea of complete chain of custody falls apart in Congo’s tens of thousands of alluvial mines. Some 18 miles (29 km) from Mwanza’s creek-side site, more than 100 men labor at the much larger Kangambala mine. They have spent four months shoveling away 50 feet (15 m) of rock and dirt to expose the diamond-bearing gravel below. None are paid for the labor; they work only for the opportunity to find diamonds. Knee-deep in water pumped from the nearby river, three men sluice pans of gravel through small sieves. One gives an excited yelp, fishes out a sliver of diamond the size of a peppercorn and hands it to an overseer sitting in the shade of a striped umbrella. The overseer folds it into a piece of paper torn from a cigarette pack and puts it in his pocket. It’s worth maybe $10, he says. That find will be split between the owner of the mine site, who gets 70% of the value, and the 10 members of the sluicing team, who have been working since 9 a.m. and will continue until the sun sets around 6 p.m. If they are lucky they will find two or three such slivers in a day.

ut the idea of complete chain of custody falls apart in Congo’s tens of thousands of alluvial mines. Some 18 miles (29 km) from Mwanza’s creek-side site, more than 100 men labor at the much larger Kangambala mine. They have spent four months shoveling away 50 feet (15 m) of rock and dirt to expose the diamond-bearing gravel below. None are paid for the labor; they work only for the opportunity to find diamonds. Knee-deep in water pumped from the nearby river, three men sluice pans of gravel through small sieves. One gives an excited yelp, fishes out a sliver of diamond the size of a peppercorn and hands it to an overseer sitting in the shade of a striped umbrella. The overseer folds it into a piece of paper torn from a cigarette pack and puts it in his pocket. It’s worth maybe $10, he says. That find will be split between the owner of the mine site, who gets 70% of the value, and the 10 members of the sluicing team, who have been working since 9 a.m. and will continue until the sun sets around 6 p.m. If they are lucky they will find two or three such slivers in a day.

The day’s findings will be collected and sold to an itinerant buyer. He in turn will sell his purchases up the chain to one of the more established agents, who will collate several packets before making the journey to Tshikapa, where the streets are lined with small shop fronts adorned with hand-painted images of diamonds and dollar signs.

Two days later a young diamond merchant ducks into Funji Kindamba’s storefront office. He spills a fistful of greasy yellow and gray stones onto Kindamba’s desk. With the help of large tweezers, Kindamba pushes the diamonds into piles with a practiced flick of his wrist, separating out the large ones from the tiny diamonds used in pavé work, where small stones are set very closely together. Eventually they come to an agreement on a price: $200. Kindamba notes down the seller’s name, the price he paid and the total carat weight for the whole packet—4.5—in a small notebook. Kindamba has no idea where the diamonds come from. “There are thousands of mines,” he says with a laugh. “It’s impossible to keep track.”

Diamond-industry experts like to say a packet of diamonds will change hands on average eight to 10 times between the country of export and its final destination. The reality is that diamonds from the mines outside Tshikapa are likely to change hands eight to 10 times before they even leave the province for the capital, Kinshasa, the only place where Congolese diamonds can be certified for export. Kindamba’s diamonds will be sold on at least twice before they reach a licensed buyer where a representative from the Ministry of Mines can assess the value and furnish the official form required to obtain the Kimberley certificate. On the line noting the location of the mine, it will simply say Tshikapa.

Given the near impossibility of tracing diamonds to their source in countries like Congo, where artisanal mining predominates, jewelers who want a more transparent supply chain usually buy from mining companies like De Beers or Rio Tinto, which control all aspects of the process from exploration to cutting and selling. Others source only from countries with good human-rights records. Brilliant Earth, for example, buys most of its diamonds from Canada. “The unfortunate reality is that there are so many problems that have to be solved before we can offer fair-trade diamonds from the Congo,” says Gerstein.

It’s a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, companies need to understand enough about their supply chains to assure customers that child-labor issues, environmental degradation or human-rights abuses do not taint their jewelry. But while the easiest way to do that is by simply boycotting certain countries, abstaining won’t make those problems disappear. In a desperately poor country like Congo—where over half the population lives on less than $1.25 a day—things could actually get worse. “Artisanal miners in Africa are actually becoming victims of our desire to do right by diamond miners,” says Bai.

According to Congo’s Ministry of Mines, nearly 10% of the population relies on income from diamonds, and the country produces about a fifth of the world’s industrial diamonds. Diamonds may bring problems, but rejecting them outright would bring even more, says Albert Kiungu Muepu, the provincial head of a Congolese NGO that, with the help of the Ottawa-based Diamond Development Initiative (DDI), is organizing miners into collectives—the first step toward establishing fair-trade diamonds. A boycott “will not change diamonds of misfortune into diamonds of joy overnight,” he says. “If those who want to do good stop buying our diamonds, rest assured, Congo still loses. The way to better conditions in Congo is to help us better our system so that the resources generated by Congo can profit Congo.”

Organizing miners into cooperatives is a key step in the process, much as it was for turning exploited coffee farmers into partners in fair trade. Not only can cooperatives pool resources for better mining equipment, they also can share knowledge and set prices according to global markets, rather than on the basis of what local buyers are offering. But unless the Kimberley Process, or some other internationally agreed-upon certification system, can assuage growing concerns about human-rights abuses, environmental impacts and fair labor practices around mining—while ensuring that tainted diamonds stay out of the marketplace—conscientious consumers may stay away.

Ironically, it is the company that has been the most outspoken about the evils of diamond mining that is doing the most to help Congolese miners right now. Brilliant Earth, with the help of DDI and Muepu’s NGO, has funded a school to get children like 12-year-old Kalala Ngalamume out of the mines and back into class. When his father died of malaria last year, it looked as if Ngalamume would be joining his neighbor Mwanza in the mines. Instead he was picked as one of the first 20 students in the Brilliant Mobile School pilot program, based on his age, his previous schooling and the fact that he was at risk of going to work in the mines. “Without school, I know I would have to do whatever it took to survive, even go looking for diamonds,” he says. But hundreds more children in his village are still at risk. “We need to do something so that all these children have an opportunity to be educated, so they won’t be poor, so they can do something with their lives.”

o how can a concerned consumer buy a diamond in a way that actually helps people like Mwanza and Ngalamume? Asking questions can go a long way. Responsible jewelers should know every step in the path from mine to market. Kimberley Process certification alone isn’t enough—as of now the system is too limited. Diamonds that come from Zimbabwe and Angola are particularly problematic. Watchdog groups have documented human-rights abuses in and around mines in those countries, though exports from both nations are allowed under the Kimberley Process—another loophole in the system.

o how can a concerned consumer buy a diamond in a way that actually helps people like Mwanza and Ngalamume? Asking questions can go a long way. Responsible jewelers should know every step in the path from mine to market. Kimberley Process certification alone isn’t enough—as of now the system is too limited. Diamonds that come from Zimbabwe and Angola are particularly problematic. Watchdog groups have documented human-rights abuses in and around mines in those countries, though exports from both nations are allowed under the Kimberley Process—another loophole in the system.

While buying diamonds from a conflict-free country like Canada can buy you a clean conscience, a better bet may be African countries like Botswana and Namibia. Governments in both countries have a solid record of working with both the industrial mining industry and artisanal miners to enforce strong labor and environmental standards. Sierra Leone—the setting for much of the film Blood Diamond—has improved as well, though the country’s recent Ebola outbreak set back some of that progress.

Consumers who care can trace the fish on their plate back to the patch of sea it was taken from. They can choose fair-trade apparel that benefits the cotton farmers and seamstresses who produced their clothing. But the lineage of one of the most valuable products that many consumers will ever buy in their lifetime remains shrouded in uncertainty, and too often the people who do the arduous work of digging those precious stones from the earth are the ones who benefit the least. The only way that the blood will finally be washed away from conflict diamonds is if there is a true fair-trade-certification process that allows conscientious consumers to buy Congo’s artisanal diamonds with peace of mind—just as they might a cup of coffee.