ARCTIC ICE IN RETREAT

text BY justin worland / pHOTOgraphS By MARIO TAMA

The effects of climate change can be felt growing slowly but subtly in most parts of the world as temperatures inch up and extreme weather occur more frequently.

But the shift in the Arctic has been sudden and dramatic with temperatures rising more severely than anywhere else on the globe. Global temperatures in February of last year averaged 1.2°C (2.2°F) higher than the 20th century average, but that number hit 16°C (29°F) above average in parts of the Arctic.

Those temperatures have a particularly damaging effect in the Arctic. Sea ice covers more than 14 million square kilometers (5.6 million square miles) at its maximum point each year.

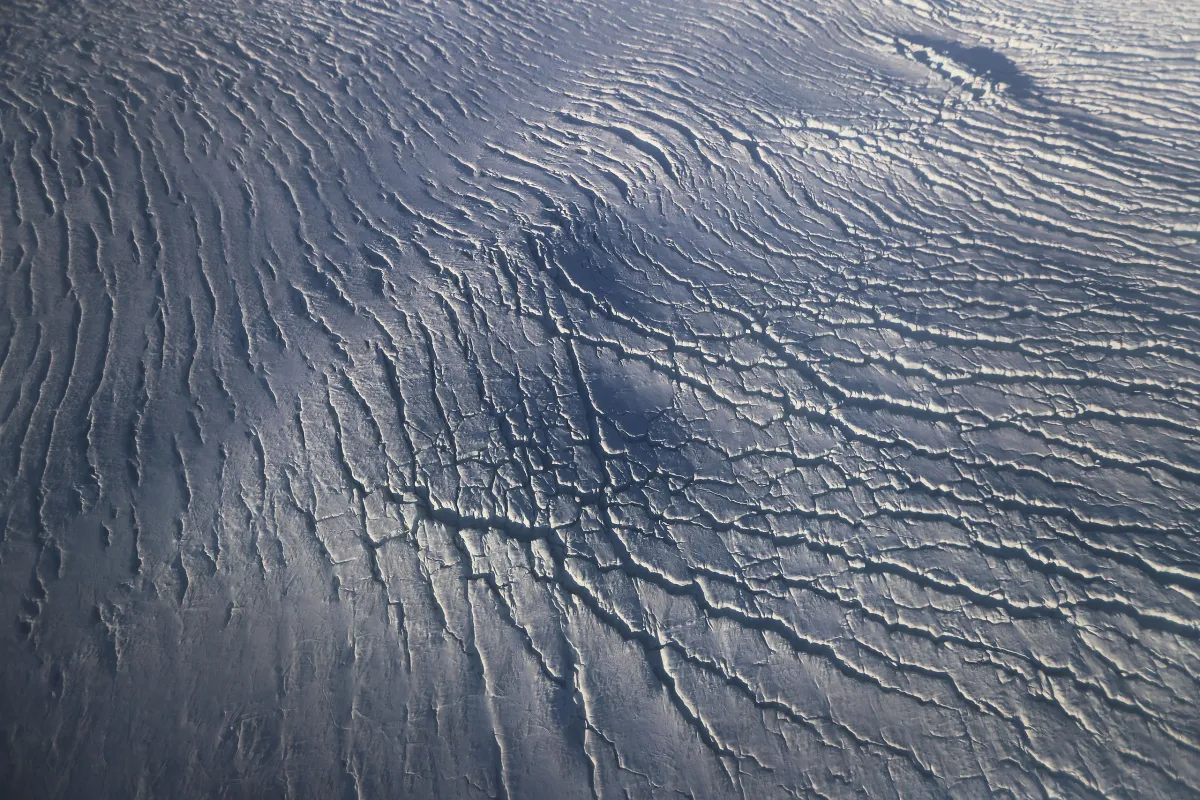

The ice sheet over Greenland captured by photographer Mario Tama covers an additional 1.7 million square kilometers (656,000 square miles). That ice melts when temperatures rise, destroying habitats and beautiful scenery while also contributing to global sea level rise.

Tama, who photographs a wide range of subjects in his work for Getty Images, understood the scale of Arctic ice when he embarked on a trip to the document the scene there in April with NASA, but the immensity of ice in the region still surprised him. “The landscapes that we were witnessing and photographing, I’ve never seen anything like it in my life,” he says. “It was like another planet.”

Tama traveled with researchers on a retrofitted aircraft from Thule Air Base located 750 miles north of the Arctic Circle on the west coast of Greenland, as they sought to learn about Greenland’s glaciers. But quiet lab scientists these were not.

Tama snapped photos aboard a flight with the researchers from the NASA project known as IceBridge. At the end of the years-long research project, NASA will have built a groundbreaking three-dimensional view of ice across both the north and south poles.

The ice sheets—which often extend as far as the eye can see—are so immense that in many cases Tama struggled to get a sense of the scale of the images he captured. “I can remember at various times just trying to process what I was looking at,” he says. “These were formations and landscapes I had never seen in my life.”

Tama’s trip came close to end of winter, the point where Arctic ice tends to cover more area than any other time during the year. This year’s maximum sea ice coverage—reached on March 7—was 500,000 square miles lower than the average for that point in recent decades, according to numbers from the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Scientists say it’s unclear how much longer formations like the glaciers captured by Tama will exist given the pace of man-made climate change. Glaciers across the globe are in retreat at a pace that can be difficult to predict with precision. Research published last year in the journal Nature suggested that Greenland’s ice sheets are less stable than previously thought and might disappear faster than anticipated.

“The scenarios at the moment basically assume a stable Greenland ice sheet,” said study author Joerg Schaefer, a research professor at Columbia University, at the time. “I think there’s a big question mark now behind that assumption.”

Correction: The original version of this article misstated how the photos were taken. The plane flew in the valleys to get closer to the ground, but the researchers did not jump out of the plane to take the photos.

Mario Tama is a staff photographer for Getty Images based in Rio de Janeiro. Follow him on Instagram @mario_tama.

Andrew Katz, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s Senior Multimedia Editor. Follow him on Twitter @katz.