The First Space Pioneers

Bettmann Archive

Animals were every bit as heroic as the first human astronauts

Animals have long been the science community’s shock troops—the first to hit the beaches when a new frontier of knowledge is being claimed. Those soldiers hardly volunteered for the misison: The thousands of monkeys and mice that were used as test subjects for Jonas Salk’s first polio vaccine were conscripted for the job, whether they wanted to do it or not. That doesn’t diminish their profound contribution to scientific knowledge—indeed, it enlarges it.

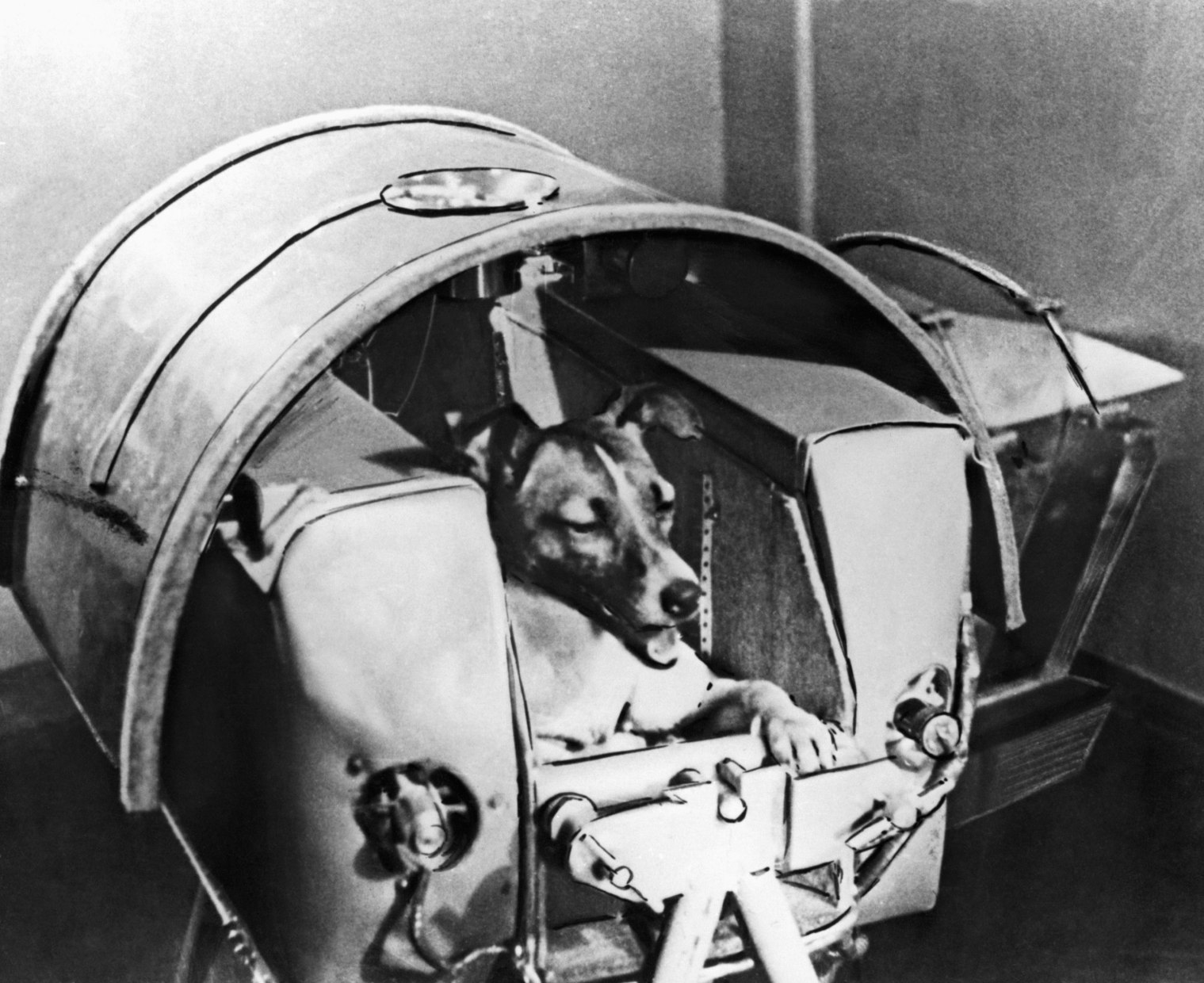

The same is true of the first animals in space. Human beings had visions of traveling above the atmosphere and out toward the moon and planets, but the survivability of such an enterprise was very much an open question. It was 60 years ago, on November 3, 1957, that Laika—an 11-lb., part-terrier mongrel, picked up on the streets of Moscow—began providing answers, when the Soviet Union launched her into orbit aboard Sputnik 2.

Less than a month earlier, when the Soviets shocked the world with the launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, the U.S. reacted with equal parts indignation, outrage and fear. But the world loved Laika, perhaps no one more than the members of the American press, who nicknamed her Muttnik.

The world worried for her too, fretting especially over whether she would survive her journey. The answer was that she wouldn’t, and that she was never intended to survive it. Sputnik 2 had no reentry system. There was enough food and water to sustain Laika for seven days, no more. As it turned out, she barely survived six hours. Sometime during her fourth orbit, she died when her cabin overheated.

Five months later, after 2,566 more orbits, Sputnik 2 reentered the atmosphere and was incinerated by the heat of reentry, cremating Laika in the process. More animals would follow, and just three years later, in April of 1961, so would Yuri Gagarin, the first human being in space.

The mutt, however, preceded the man—as well as all of the other women and men who will ever leave the Earth. Laika, the involuntary pioneer, is owed our thanks.

1957 Laika

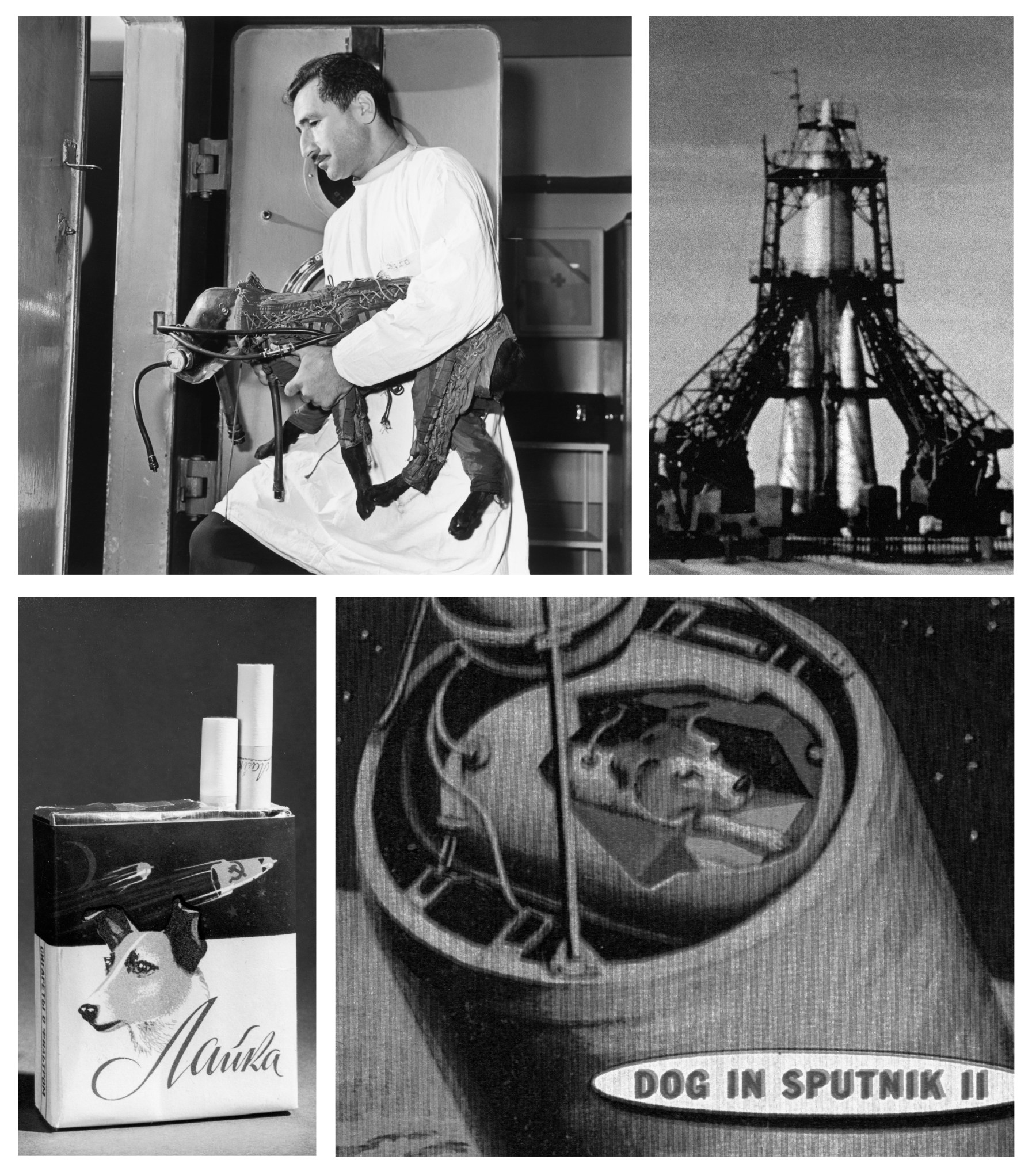

Andreas Cellarius

(Clockwise from left): Astronauts need spacesuits and that’s true whether they’re canines or humans. Laika’s lace-up suit included a helmet contoured to a head with a snout, and an oxygen supply in the event of a pressure leak. The rocket that lifted Laika to space was dubbed Sputnik 2, but that concealed its ominous pedigree: it was actually a modified R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile. Western media covered the launch with helpful illustrations, while Eastern marketers—nominally non-capitalist—did not hesitate to cash in on the Laika brand.

1959 Able & Baker

Rollins/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Rollins/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Getty Images

Getty Images

It was all harmless fun at first for Baker, a squirrel monkey, and her space travel companion, Able, a rhesus monkey, in the run-up to their 16-minute space flight on May 28, 1959. But the trip aboard the thundering Jupiter-C rocket, which took them 300 miles high and nearly 2,000 miles down range, left them shaken, as the post-flight picture of Able, above, suggests. She would live just four more days, dying of cardiac fibrillation while under anesthetic as doctors were removing electrodes that had been used to beam her vital signs back to Earth. Baker fared much better, dying on November 29, 1984 at the respectable age of 27.

1960 Belka and Strelka

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Andy Lauwers—REX/Shutterstock

Andy Lauwers—REX/Shutterstock

Belka and Strelka looked a lot livelier on August 20, 1960, after their return from nearly a day in space than they do now, taxidermized and displayed at the Cosmonautics Memorial Museum in northern Moscow. Either way, they were frisky critters. They were just the most conspicuous members of the crew aboard their spacecraft, which included 40 mice and two rats. All survived the journey, and Strelka even went on to have a litter of six puppies. One of which, named Pushinka, was given as a gift to President John Kennedy, and later went on to have a litter of her own with a Kennedy family dog. The President referred to the babies as pupniks.

1961 Ham

Bettmann Archive

Bettmann Archive

Ralph Morse—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Ralph Morse—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Ralph Morse—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Ralph Morse—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

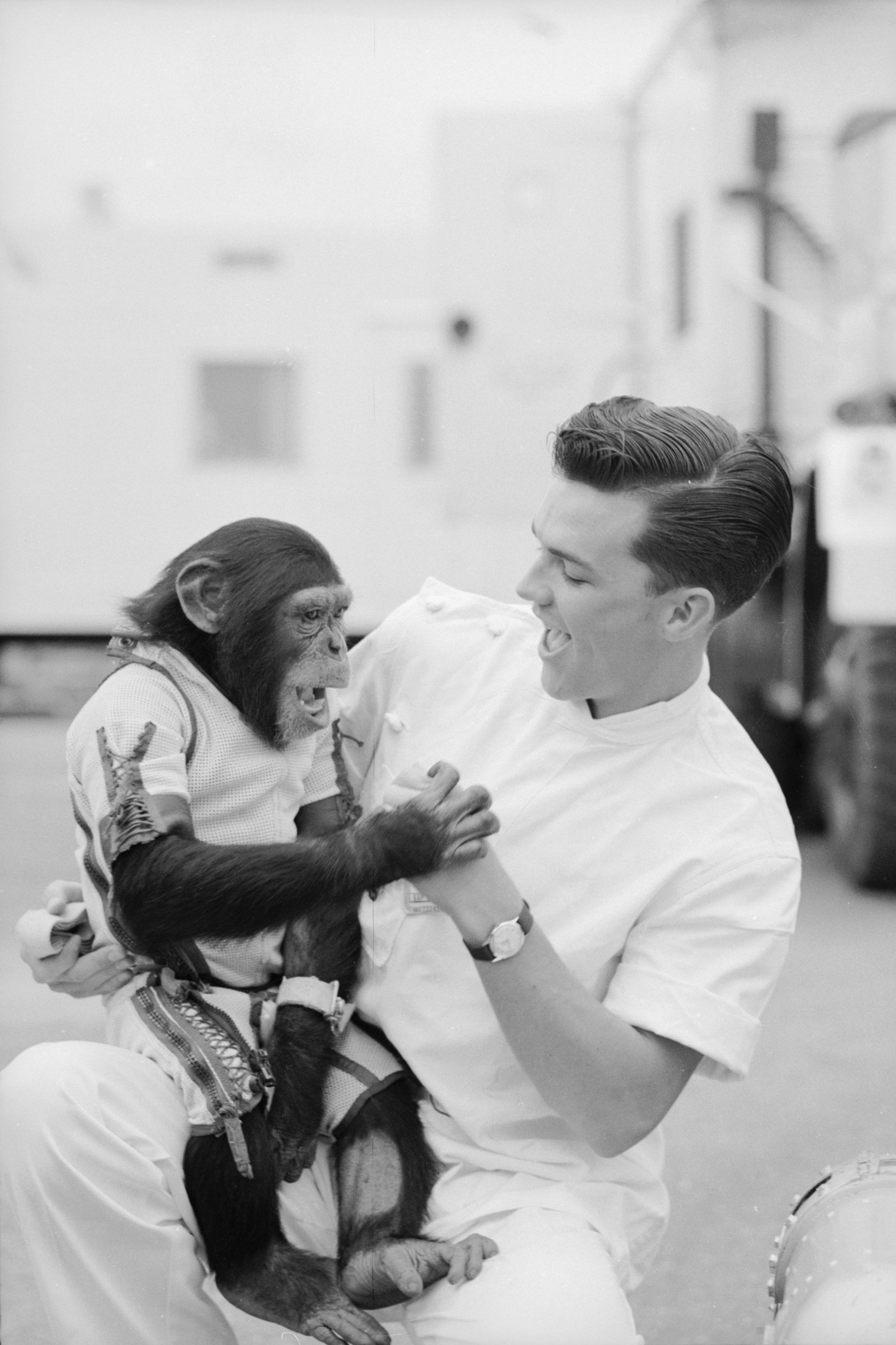

America’s first astronauts did not much care for Ham, the four year old Cameroonian chimpanzee who preceded them into space, on January 31, 1961. Ham, after all, was flying in the same spacecraft that was being built for the men. His mission profile—a 16-minute suborbital flight—was also the same one astronauts Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom would later fly. Like the astronauts too, he rocketed to space aboard a Redstone rocket (above). Ham’s flight, however, was essential to determine if humans could survive a journey in the tiny Mercury spacecraft. By throwing levers in response to a flashing light, Ham also proved that it was possible to concentrate and work under the stressors of flight. Ham played happily with a lab worker after returning to Earth and, like Baker before him, went on to live a long life, dying on January 19, 1983, at the age of 26.

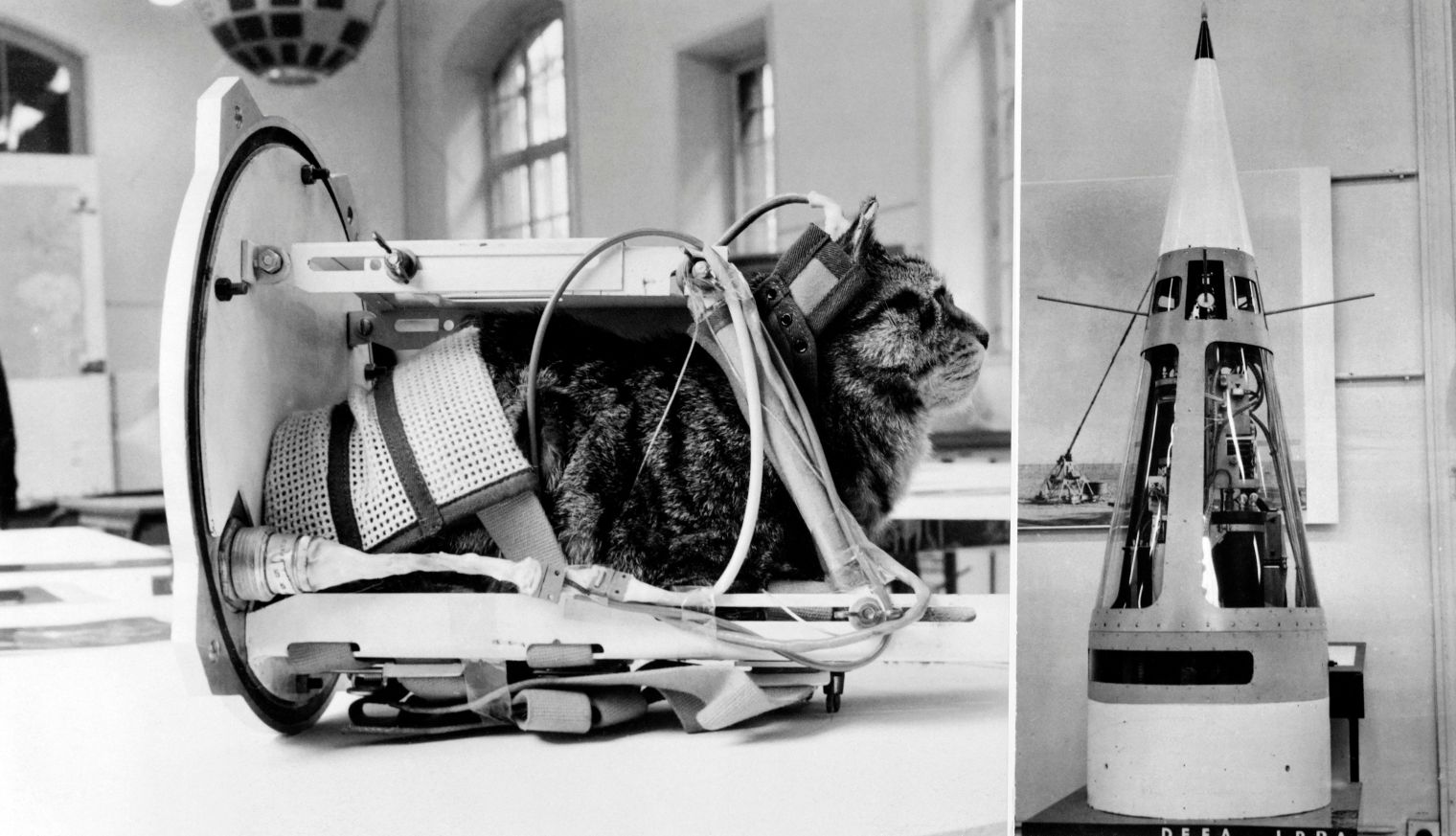

1963 Felicette

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

France’s first astro-critter came late to the space game. Her name was Felicette and she was launched on a 15-minute suborbital flight on October 18, 1963. By then, the U.S. had already launched half a dozen astronauts, and the Soviet Union had sent an equal number of cosmonauts, including Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. But France staked its claim all the same, and Felicette became the first cat to make the journey. She almost didn’t. A male cat named Felix was supposed to fly the mission, but he escaped shortly before launch day and his place in history went to his backup instead.