Interviews By Mandy Oaklander

Photographs by Erik Tanner for TIME

Some 2.6 million Americans have served in Iraq and Afghanistan, which means at least that number of families have experienced the anxiety in seeing a loved one sent off to war, the pride in their service and the fear that they won’t come home.

My family knows those feelings. My younger brother, Sean Walsh, graduated from the Army Ranger School and was a first lieutenant and rifle platoon leader when he was deployed to Iraq with the 2nd Stryker cavalry regiment in the August of 2007. We emailed him. We worried. And most of all we hoped that every one of the more than 400 days of his tour of duty, that we would see him again, safe and whole.

We were lucky. Sean served with honor and came back to us, though the Type 1 diabetes he developed suddenly in 2011 eventually forced him to leave the Army. Not every family was so fortunate. More than 600,000 Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans have been left partially or totally disabled from physical or psychological wounds received during their service. And their families, too, have felt the aftershocks of war here at home, witnessing a loved one suffer and doing everything they can to help—even when everything isn’t enough.

That’s what makes the Defense Department’s Warrior Games so important. The 270 Wounded Warriors competing in a variety of sports from June 19–28 at the Marine Corps Base in Quantico, Virginia, come from every branch of military service. Some were injured or became ill on the battlefield—others in civilian life. What they have in common is the will to overcome—the same will that led them to serve in the first place. The Games give them a place, as the injured veteran Redmond Ramos says, to “finally live life” once more.

You can read the stories of 15 of those Wounded Warriors, how they served, how they were injured or became sick and how they found their way to the Games. You’ll see strength and determination in these stories—and you’ll also read of families that feared for them when they fought, supported them when they came home hurt and will cheer for them now. Sean will be one of those Wounded Warriors, competing in cycling. I didn’t think I could prouder of him than I was the day he returned home from Iraq. I’m so glad I was wrong. —Bryan Walsh, TIME Foreign Editor

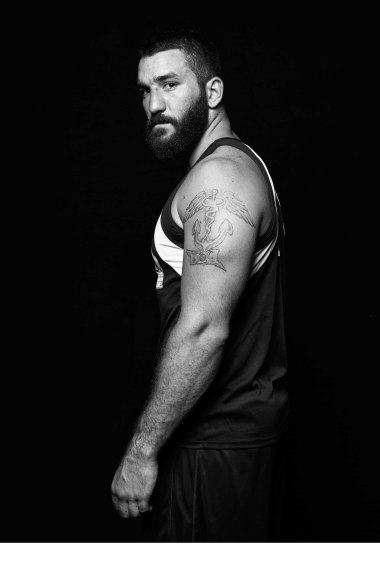

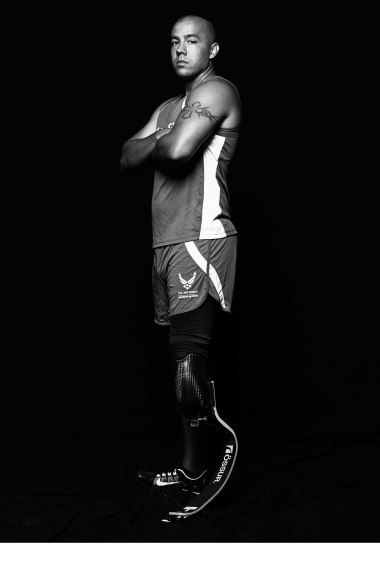

Redmond Ramos

Service stats: Retired U.S. Navy Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class

Events: Sitting Volleyball, Swimming, Track & Field

Current location: Murrieta, Calif.

Injury/illness: Leg amputation after an IED explosion

Growing up with two older brothers and a younger stepbrother, life has always been competitive. After graduating high school, it was only natural for me to follow in their footsteps and head to boot camp to become a Navy corpsman, serving with the Marines. I later deployed to Afghanistan as a combat replacement for 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, where I stepped on an improvised explosive device. After the doctors told me I wouldn’t run again if I kept my left leg, I opted for amputation. I was fortunate to get back on my feet and compete in the Warrior Games only seven months later, bringing home five medals.

When you are injured and lying in a hospital bed, you face a choice: feel sorry for yourself and drink the pain away, try to get back to the person you used to be, or open your eyes and finally live life. Become better than you ever were.

When adaptive athletics became a part of my life, I had a healthy goal again. I worked to become a little faster or stronger. Saturday nights were spent at the gym instead of the club. “Sunday Funday” meant early-morning adventures, not late afternoons hungover.

The more time I spent at the gym, the happier I became. The more I focused on improving myself and giving back, the better I felt. When I left the military I started teaching corpsmen, Marines and police officers combat trauma medicine. I later started working for the Elizabeth Hospice Center, which honors the service of veterans with six months or less to live. After thousands of people helped me recover, I found happiness in helping others. I cannot tell you where I’d be right now without adaptive athletics, but it surely wouldn’t be here.

Kristen Esget

Service stats: Retired Coast Guard Yeoman 3rd Class

Events: Shooting, Swimming

Current location: Ridgeway, Va.

Injury/illness: Traumatic brain injury and knee damage after being hit by a car

I come from a military family, so it felt very natural to enlist in the Coast Guard in 2008. I trained as a yeoman because I wanted to build skills I could apply in the civilian workforce should I separate from the military. Just three years later, I was medically separated from the Coast Guard after I was hit as a pedestrian by a drunk driver. I sustained a traumatic brain injury and damaged my right knee. Since then, I’ve had to work through a lot of cognitive issues, insomnia and aphasia. I had to learn again how to write with my dominant hand, and I still sometimes have trouble reading.

But my hard work throughout my recovery has paid off. Today, four years after my accident, I teach autism awareness, I volunteer for a local rescue squad, and I help new Emergency Medical Technicians pass their state practical exams. And, of course, I participate in adaptive sports, thanks to Navy Wounded Warrior (NWW)—Safe Harbor.

NWW truly saved me. When I was feeling very low, a staff member contacted me about a sports camp, and since then, my life has truly changed. Back home, people don’t always understand me and the struggles I face because I look perfectly normal. When I am with fellow wounded warrior athletes, I do not feel judged, and I never have to explain myself. Events like the DoD Warrior Games remind me just how lucky I am. I have teammates who are missing limbs and who are confined to wheelchairs, yet they accomplish a great deal. Every time an EMT tells me he or she can’t do something, I remind them that they can—and that there are many others who do so much more with less.

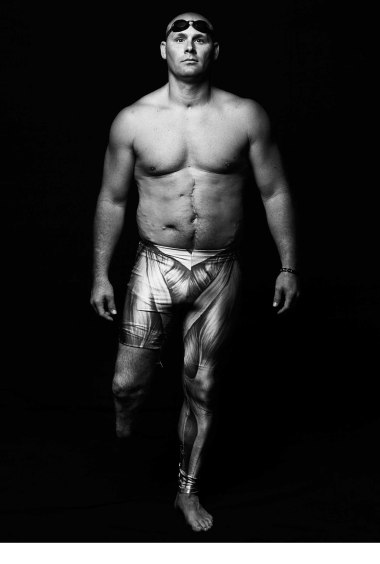

Brett Parks

Service stats: Retired Navy Aircrewman

Events: Field, Sitting Volleyball, Swimming

Current location: Jacksonville, Fla.

Injury/illness: Shot while helping a man being robbed at gunpoint, leg was amputated while in a coma

Steam rises from the asphalt of the track after a common Florida afternoon shower. The rains didn’t cool off the June heat; on the contrary, it’s now intensified by a blanket of humidity. Any sane person in Jacksonville would be indoors right now. But I am not that person. I represent the down, the distraught, the broken. The DoD Warrior Games is right around the corner, and I intend to make a statement.

It’s my fourth 100-meter today and my legs begin to burn. This is my first time sprinting in over two and a half years, and my body is constantly reminding me of that fact. I keep wondering why I put myself through this. Then, I think about how I was injured: how I intervened during a robbery and a bullet ultimately robbed me of my lower right leg. I think about other wounded warriors—whether they were recently diagnosed with a serious illness or finding a new normal after combat—and all they are fighting to overcome.

I’m doing this for them, and for the ones who will come after them. Those who need to see that broken doesn’t mean broke, and that their tragedy can become an opportunity to accomplish something great. I’m doing this for my teammates, my son, my daughter, my wife, my God.

Any sane man would call it a day and spend the rest of it on the couch in an air-conditioned room, but, of course, I am not sane. I still have to head to the weight room, the pool, the volleyball court and throw shot and discus. “Once more unto the breach, dear friends,” Shakespeare once said. Yes, Mr. Shakespeare, I agree—once more.

Parks is the author of a new book, Miracle Man.

Jim Castaneda

Service stats: Retired Navy Honorary Chief Boatswain’s Mate

Events: Field, Shooting

Current location: San Antonio

Injury/illness: Stroke and seizures

Written by his daughter, Mariaa Castaneda:

My father, Jim Castaneda, suffered a stroke during muster aboard U.S.S. Tortuga (LSD 46) in October 2007, and since then, his road to recovery has been long and often difficult. But one wonderful highlight has been the DoD Warrior Games.

It all started with his experience in the first-ever Warrior Games in 2010, where he participated in track and field and swimming. Initially, he was skeptical about the Warrior Games and how he could participate after his injury, but he was so glad he went.

In the coming years, my father lost mobility on his right side, but he still found ways to participate; he even took up one-handed archery, in which he uses his teeth to pull the bow! During that time, he also participated in other adaptive sports outside the Warrior Games, such as air rifle tournaments in the Texas Regional Games and hunting competitions with Freer Deer Camp. He has also participated in various sports with the VA in San Antonio, the Paralyzed Veterans of America San Antonio Chapter, and the Southwest Valor Games.

Adaptive sports still present challenges for my father. Due to his injury, it has become difficult for him to concentrate and focus, which causes him to tire easily while participating in sports.

Though the recovery process has been tedious for my father, one thing he never lost was his optimism and outgoingness. He loves the world to which the Warrior Games introduced him. The Games have shown him that there are people facing challenges like his own, and together they can still bring smiles to each other’s faces. The Warrior Games have connected our family to an annual event we know he’ll enjoy—one that will give us stories to tell for years to come.

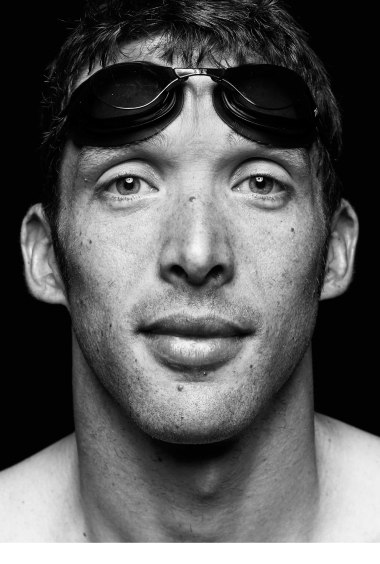

Sean Walsh

Service stats: Retired U.S. Special Operations Command Captain

Events: Cycling, Running, Swimming

Current location: Alexandria, Va.

Injury/illness: Adult-onset Type 1 diabetes

I returned from a mission overseas with classic symptoms of Type 1 diabetes. I went from running marathons and long-distance triathlons to nearly passing out on short runs. After a few weeks of denial, I went to the doctor, and a few days after my 29th birthday, I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes.

The biggest struggle for me was finding out that I wasn’t invincible, that I had to be careful now. But as I was in the hospital learning how to manage my diabetes, I found out about all the incredible things that athletes with diabetes accomplish. There are diabetic athletes in the NFL, in Formula One racing, and, most inspiring to me, an entire world class professional cycling team where everyone is Type 1.

Learning about these incredible athletes motivated me to redouble my efforts to become a better athlete. I quickly found a connection between my diabetes and sport. By better managing my diabetes, I became a faster runner and cyclist, which in turn motivated me to be in better control of my diabetes.

My training also helped me transition from the Army. Sports became a critical link between my new identity and my time as a Solider. While I was familiar with the Warrior Games before I got sick, it wasn’t until I joined Deloitte that I realized what big a deal the Games are—from intense level of competition and camaraderie to the deep commitment from the Department of Defense and veterans foundations.

Initially, I saw the Warrior Games as a way to stay connected with other Special Operations veterans and participate in their training program, but the journey became so much more than that. I am now a part of a team again, representing the U.S. Special Operations community. It is an incredible honor and I am humbled by the support I’ve received. I was blessed to have served this great country. The Warrior Games remind me that we have an obligation, whatever our circumstances, to pursue excellence in all we do, both in sport and in life.

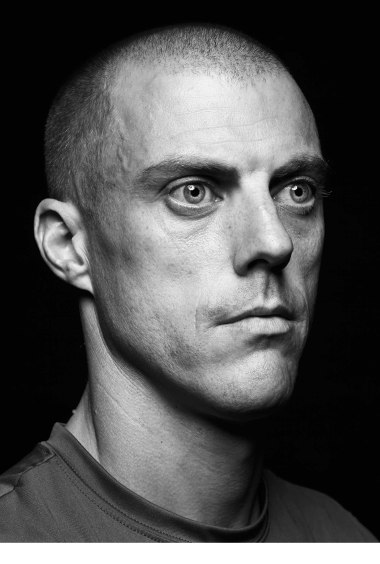

Timothy McDonough

Service stats: Retired U.S. Air Force Technical Sergeant

Events: Rifle Shooting, Archery

Current location: Spokane Valley, Wash.

Injury/illness: PTSD, traumatic brain injury, seizures, right upper extremity disability

I was a flying crew chief and it was our role throughout both wars to bring home HRs—human remains—from the combat zone. The first couple of times you do it, you’re proud. You feel that you are blessed to take home our nation’s fallen heroes to their families. Over time, though, you become quite numb to the fact that there are HRs down in the cargo box. Numb to what is going on around you. Numb to your friends and family. All your emotions shut off. Then the sleep deprivation and the night terrors start.

Before long, your body breaks down as well. I had nine service-related surgeries—on my cervical spine, my shoulder, my wrist and an elbow. My doctor down at Bethesda Naval Hospital told me due to my arm damage, I would never again do things I loved again like archery, rowing and rock climbing—basically anything that required upper body strength. This made me bitter and angry at the whole world. It not only took me out of action; it also exacerbated the PTSD.

I would jump and startle at the drop of a hat. I started hearing things that weren’t there—”auditory hallucinations”—and the only time I felt comfortable in my own skin was when I was alone out in the woods. I would disappear for hours on end, and when it started becoming days, my wife was extremely concerned. I didn’t care if I lived or died anymore. I just wanted the pain and useless feeling to stop.

Then, in 2012, I met a woman who would later become like my adoptive Momma. Her name is Mary Ellen Whitney. Momma runs a place in New York called Stride, which teaches adaptive sports to youth with special needs. There is also a Stride Warrior program for vets. On my first outing with Momma, she and her husband LJ took me snowboarding. I never thought I could do it: my spine caused balance issues, I was also terrified that if I fell and hit my shoulder, the pain that I would be in would kill me. At one point I said to Momma: “I am disabled.” She replied: “You will learn to turn dis-ability into this ability.”

About 18 months ago I went to my first Air Force Wounded Warrior adaptive sports camp. I was in the pool floundering and turning in circles. The swim coach jumped in with me and asked me what the hell was I doing. My reply—”Trying to swim”—didn’t go over well. She looked at me and said, “Stop trying so hard to not swim. Take your damaged arm put it in your hand in your pocket. Pretend it’s not there. Use the good one and the good one only.” Before I knew it I was at one end of the pool and back. Something clicked in my head. What else can I do? I went and saw the shooting coach, and then cycling and archery.

A few short months later I was at the very first Wounded Warrior Air Force Trials. I took a bronze on freestanding rifle shooting. More recently, I earned the first ever Recurve Archery Gold for the AF trials. I’ve also become a mentor for others and was given the Care Beyond Duty Mentorship Award. Not only have I been pushing myself, I’ve also been inspiring and pushing other wounded, ill and injured airmen.

Momma gave me the saying and I live it every day of my life now: “Turn dis-ability in this Ability.” I don’t believe you are ever cured of PTSD. You learn to live with it. And adaptive sports are one of my tools for living with it. I will survive this.

Benjamin Koren

Service stats: U.S. Air Force Technical Sergeant

Events: Archery, Track, Volleyball

Current location: Luke Air Force Base in Glendale, Ariz.

Injury/illness: Cancer

I was stationed at Yokota Air Base in Tokyo, Japan, and was almost at my five-year point of remission from testicular cancer. I had just gone through my annual scan and doctor visit without a hitch, felt healthy, and was focused on my career and enjoying family time overseas. That’s when I got kneed in the chest while learning Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and thought I might have cracked a rib. It turned out that my ribs were ok, but the doctors saw a tumor in my chest wall and wanted to get additional imaging to investigate. After performing a CT scan and MRI, they identified at least five tumors and sent me to Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii. A biopsy of one tumor revealed that it was the same cancer I’d had before.

I never returned to Japan after that. Instead I was assigned to the Patient Squadron at Luke Air Force Base in Phoenix, AZ, and began 12 grueling rounds of BEP Chemotherapy. While there, I received an email that said the Air Force Wounded Warrior Program had an introductory adaptive sports camp coming up designed just for people like me. At first I felt like they must have made a mistake because I wasn’t injured in combat, but after attending this camp, I realized there are many different types of wounded warriors with many different injuries and illnesses—and found that I fit right in.

I made a ton of friends and benefited from talking to other warriors who had gone through similar experiences. And I love to compete, so I didn’t have to think twice about going to the Warrior Games trials in Las Vegas. That’s what brought me here. I am still recovering from some of the negative effects of chemotherapy but am in remission again, have been returned to Active Duty and am a member of the Air Force team at the Warrior Games. I feel very blessed and excited for what the next two weeks will hold for my teammates and I, and for what the Air Force Wounded Warrior program will do for others in the future.

Krystoffer L. Bowman

Service stats: U.S. Air Force Technical Sergeant, 13th Air Support Operations Squadron

Events: Volleyball, Cycling

Current location: Fort Carson, Colo.

Injury/illness: PTSD, traumatic brain injury, hemorrhages, occipital neuralgia

On my numerous combat deployments as a Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC), there was no room to hurt or allow pain to interfere with my job. These inherent denials accumulated over my last 19 years of service and now I have what is a “Pandora’s box” of medical challenges that have driven me to retire early from service. When I was told my medical limitations would limit my deployments and my ability to do my job, life as I knew it came to a sudden halt. I began to lose purpose with myself and our family. I began to feel as a burden. For so long I worked hard and believed deeply in what I did.

In the winter of 2014, a teammate who was also getting ready for medical retirement approached me. He said I needed to contact the Air Force Wounded Warrior Program’s Regional Care Coordinator, Denise O’Connor, because I could be given a chance to heal myself. Within a week of speaking with her, I was contacted by Air Force Wounded Warrior Program’s Kimberly Radice, who showed such genuine interest and compassion in me. She patiently spoke with me for over two hours.

In January 2015 I joined the program. It brought me back to the spirit I had held for so many years, the unconditional mindset of not accepting restrictions on my life—of finding an adaptive way of thinking and finding ways to get me back into living. Before my medical issues, I was an avid outdoorsman, triathlete, diver and sky-diver. It all fed my competitive nature and desire to shatter through any wall put before me.

Now, with their assistance over the last six months, I not only woke up that sense of purpose, I also placed as a primary athlete with the Wounded Warrior Team. I will proudly represent our Air Force, our staff and coaches, our Team and our recently lost teammate, Master Sergeant Richard Gustafson. No one fights alone.

Lisa Marie Hodgden

Service stats: Retired U.S. Air Force Master Sergeant

Events: Cycling, Field

Current location: Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City

Injury/illness: PTSD, traumatic brain injury

I think of who I was six months ago and barely recognize myself. I was angry, bitter, and resentful. I didn’t trust anyone. I wanted to be left alone. I pushed people away. I hurt my family and friends and grew more bitter and angry by the day. It was no one’s fault but mine. When Kim Radice, my Air Force Wounded Warrior Care Manager, called me to tell me about the Adaptive Sports camps, I laughed. Hard. To the point where I choked. I am the least athletic person on this side of the planet, and my name is not synonymous with any sport. So I told her I was not interested. About twelve phone calls later from various AFW2 staff members, I reluctantly said I would go. After numerous panic attacks and several nervous breakdowns, I boarded the plane.

As Wounded Warriors arrived at the hotel, I listened to their stories. I came to a sudden realization: that’s my story! I found different sports that I could do because they adapted them to me. After that camp I came home different. My family noticed immediately. These camps are about focusing on the things I can do, not the things I can’t. I have a network of people who I can trust and reach out to for help. I understand I am not alone. My family isn’t alone. With coaches, staff and fellow athletes by my side, I began to let go of the old me. I am a work in progress; I always will be. I know it will be alright, one day, one moment at a time. I am now closer to the person my family deserves. Practicing for the Games helps me focus on the positive. I don’t need a medal in competition—I have already won.

Rey Edenfield

Service stats: U.S. Air Force Staff Sergeant

Events: Archery, Shooting, Sitting Volleyball, Track

Current location: Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Ala.

Injury/illness: Lower leg amputation

On October 28, 2013, I was involved in a motorcycle accident that crushed my left heel. After four weeks and several surgeries to save my heel, my wife and I decided the best option for our family was to amputate my leg. My main concern was to be able to continue serving in the military as well as live a functional lifestyle. On November 25, my left leg was amputated below the knee and my life was forever changed.

I got my first leg on February 10, 2014 and was walking unassisted three days later. I didn’t waste any time getting back in shape. I started going to the gym every day, learning to adapt and overcome all the new obstacles in my life.

Eventually, I was returned to active duty and things were starting to feel normal again. Then in mid January, I got a phone call from my Recovery Care Coordinator telling me about an adaptive sports program. Initially I was hesitant to apply because I did not compete much growing up, but once I arrived to the Air Force trials and learned about what adaptive sports really are, I was hooked! I was fortunate to make the Air Force team and have the opportunity to compete in track, archery and shooting.

The biggest impact that the Air Force Wounded Warrior program has had on my life is that it’s given me a new perspective on life as an amputee and has opened my eyes to the world of adaptive sports. I had no idea the programs and opportunities that were available to me. I have had a blast over the last few months learning new sports and seeing improvements throughout my training. After the Warrior Games, I will continue to train and try new adaptive sports and just see where it takes me.

Anthony Rios

Service stats: Retired U.S. Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant

Events: Cycling, shooting and sitting volleyball

Current location: Oceanside, Calif.

Injury/illness: PTSD, traumatic brain injury, left leg injury

May 8, 2010, I was wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade in Marjeh, Afghanistan. My mentality was to “tough this out,” until my idea of normalcy returned. Unfortunately, reality would send me down a different path, and the unspoken truths about being injured would become my new norm. I struggled to find my way out of this fog of pain and uncertainty, and one of the beacons would be adaptive sports and recreation.

As a U.S. Marine, exceeding daily challenges is expected of every Marine. As a patient, I was embarrassed to admit I couldn’t perform my duties, or even function as a normal person. For the first two years, friends and family had no idea I was even hurt. I thought, “If I can’t understand what is wrong with me, how can I expect anyone else to?” My diagnosis of traumatic brain injury and PTSD would be much more difficult to handle than my physical injuries. I would endure extensive medical appointments and evaluations and be introduced to a variety of therapeutic activities. Although the medical and mental health professionals gave me an understanding of my situation, adaptive sports like seated volleyball, hand cycling and shooting gave me a feeling of purpose and a new sense of challenge in my life.

Venues such as the DoD Warrior Games allow me to display how hard I’ve worked to get to this point, but more importantly, the camaraderie and branching out to the public gives me more therapeutic value than any pill or counseling session I’ve ever had. I’ve not only gained focus and patience, but confidence that I am relevant, and through this type of exposure, I can say, “I’m not ashamed of who I am, and glad God had faith in me to endure it.”

Adaptive sports have helped the brothers and sisters that I’ve bonded with in battle find purpose in our struggle, and although we haven’t perfected an exact science, I’m positive if we’ve found our way out of this fog once, we can damn sure do it again.

Jenae Piper

Service stats: Retired U.S. Marine Corps Sergeant

Events: Cycling, Field, Sitting Volleyball and Shooting

Current location: Oceanside, Calif.

Injury/illness: PTSD, Spinal Injury, Right Hip Full Labral Repair

The DoD Warrior Games and Marine Corps Trials give me a new purpose and the opportunity to set and reach new goals. My transition out of the military into medical retirement has not been easy; my recent hip surgery, determining my new abilities and figuring out how to make the best of the situation seem to always be my next challenges Adaptive sporting events bring me back to a group of friends and family that are faced with similar challenges but all have the same goal, which is to win and do their best at whatever sport they’re competing in. I played soccer for 18 years, and seated volleyball is just as fast and competitive but more difficult with all the obstacles and rules. Like soccer, I get the same rush of adrenaline and sense of purpose that my team is depending on me. I find myself lost in the moment, which is exactly where I want to be. The feeling that there is nothing else in the universe but that intense excitement I get while playing a competitive sport—I thrive for that feeling all the time. The feeling of belonging and being depended on comes in at a close second.

The individual sports are all about doing my personal best and being able to mentally and emotionally stay in the game. Yes, I am still a part of a team and they support me, but this is personal. It is centering mental focus to overcome any pain, doubt, and inability you might have, in order to finish the match the best way you can.

At the end of the Games, I would hope to leave with a medal in every event I competed in, along with the motivation of what it took to get to that point. Not every athlete here will take home a medal, but what they will gain is a new sense of pride competing against so many physically strong competitors. In the end they are finding their strengths, both physical and mental.

Nicholas Titman

Service stats: U.S. Army Sergeant

Events: Swimming, Track, Cycling, Sitting Volleyball, Wheelchair Basketball

Current location: Fort Carson, Colo.

Injury/illness: Injuries to lower back

I suffer from degenerative disc disease from my L2-S1 vertebra, and since my injury it has been an uphill battle both mentally and physically. There have been days I was unable to get out of the bed, but there have also been days that I am able to go out and do the things in life I love so much.

After my injury, I was told I would never be able to compete in sports at the level I had before. Volleyball, track and basketball were always a huge part of my life, and I knew that I would not settle for anything less than being back on the court and track. In 2014 I was placed in the Warrior Transition Battalion at Fort Carson, Colo., and given the time I needed for my healing and recovery. The day I arrived I knew that I would be able to focus on getting back into the sports I loved so much.

It took about two weeks for me to understand my whole outlook on life and sports would be changed and that I could play the sports I wanted so desperately to play. Becky Richardson, Adaptive Sports Coordinator at Fort Carson, introduced me to Sitting Volleyball and Wheelchair Basketball. At first, it was really tough and I wasn’t the biggest fan of either sport, but with drive and determination I started getting better and better. She was also able to help get me back on the track. I may not be where I was a few years ago before my injury, but it’s a stepping-stone, and I know I will get back to that point. I am so thankful to have such a great support system, not only at work but also at home. My partner has encouraged me since the beginning and he has believed in me all the way. I believe that no matter where you are at, or what challenges you are facing with your injury or illness, keep fighting and don’t give up on your dreams.

Jasmine Perry

Service stats: U.S. Army Corporal

Events: Swimming, Track, Field, Archery, Wheelchair Basketball

Current location: Fort Campbell, Ky.

Injury/illness: Left leg amputation

I’ve always been competitive, having played basketball, softball and soccer in high school. I also played basketball in college. In May 2005, I was injured during a training exercise in Fort Carson, Colorado, and during a year of more than 13 operations, I had to make the decision of whether I wanted to have my left leg amputated. The hardest part for me was dealing with the limb, the year in between. Once my amputation was done, I got fitted with my first prosthetic on a Thursday. That Saturday, I was at a park playing basketball. I had to make that decision; it’s a mental decision. I haven’t complained once since it’s been amputated. In 2010 I was sent to the Center for the Intrepid, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. I became active in adaptive sports at the CFI. I was the first Soldier to complete the motorcycle safety course using adaptive equipment. I volunteer at my local community center, Habitat for Humanity, our local homeless shelter, and am an avid hunter.

My amputation has made me more resilient. It built me up mentally; I can handle just about anything mentally. It humbles you. It tests your character. It shows what type of person you really are and how you will overcome.

Training for the 2015 Department of Defense Warrior Games prepares us mentally. Physically we’re ready for the Marines or any other branch when the time comes. My main drive for the games is to just finish with a positive attitude, to give it everything I have, and hopefully that rubs off on the team. Winning is a fulfillment and accomplishment for the team as a whole: to bring back the Chairman’s Cup to Team Army.

Haywood Range

Service stats: Retired U.S. Army Specialist

Events: Swimming, Track, Field

Current location: Palm Beach Gardens, Fla.

Injury/illness: Right arm amputation

I enlisted in the Army as an Infantryman. While I was assigned to 1st Brigade, 10th Mountain Division in September of 2012, our unit was in the National Training Center, Fort Irwin, California, preparing for a deployment to Afghanistan. After receiving special training to be a gunner in a high mobility multi-purpose wheeled vehicle, my team was involved in a rollover accident that changed my life. During a rollover, team members inside the vehicle would normally pull the gunner, who is manning the turret, inside the vehicle. It happened so fast they didn’t get a chance to pull me in. The vehicle rolled a least eight times.

I never had a plan A or B for my life—or a five-year plan. I thought life just worked itself out. I’m right handed. I wondered, “What am I gonna do now?” When I was in the hospital, after having my right arm amputated, I thought life was basically over. I wondered why this happened to me.

In rehabilitation, I met people who were like me and they were doing all kinds of things—including adaptive sports. They were happy and smiling and in good spirits. Other wounded warriors told me to change how I thought, from “can’t do” to “can do”. I did change my mind and developed stronger faith in God. My amazing wife, God, family and friends have helped me overcome.

I can’t believe everything that is happening right now. I will leave Virginia for a few days during the DoD Warrior Games to go throw for the U.S. Paralympics. My favorite experience in the Department of Defense Warrior Games is the camaraderie with the team. We’re able to overcome our illnesses and injuries together. I understand now that with God all things are possible, even with just one arm.

Produced by Alexander Ho and Marisa Schwartz Taylor