Like many people, I loved the movie Frozen. When I got to the theme song “Let It Go,” sung by one of the movie’s two heroines, who has decided to let go of all the suffocating expectations about how a princess should behave and finally use her long-suppressed magic powers, I wanted to cheer. Women not only have to let go of society’s traditional expectations about who a woman should be and what she should do. We also have to let go of our own expectations about who a man should be and what he is and is not good at.

irtually all the women I know and most of the women in my audiences have deeply embedded stereotypes about men in the home. I certainly indulge them myself. I often laugh with other women about “male looking”: that phenomenon when a man opens a cabinet in the kitchen, stares blankly straight ahead, and then yells, “Where’s the peanut butter?” Typically it’s right in front of him. I’ve also often said that “my husband believes in Santa Claus,” because as far as he’s concerned Christmas just magically appears, stockings and all. With an audience of women, this line never fails to get a knowing chuckle.

irtually all the women I know and most of the women in my audiences have deeply embedded stereotypes about men in the home. I certainly indulge them myself. I often laugh with other women about “male looking”: that phenomenon when a man opens a cabinet in the kitchen, stares blankly straight ahead, and then yells, “Where’s the peanut butter?” Typically it’s right in front of him. I’ve also often said that “my husband believes in Santa Claus,” because as far as he’s concerned Christmas just magically appears, stockings and all. With an audience of women, this line never fails to get a knowing chuckle.

A certain amount of gender teasing is completely fine and funny. Given that our household is three men and me, we all indulge in plenty of eye rolling about male and female differences. Overall, I am happy to acknowledge and embrace gender differences.

But I’m not talking about difference here. I’m talking about presumed superiority: the ways in which a majority of American women actually think we are better than men in the entire domestic realm, from kids to kitchens. About the things we don’t actually want to give up. And about the roles many of us want men to play and the roles we are willing to let them play.

Consider the following scenario. You walk into your office on your first day of work and your boss, a man, says, “I have evolved biologically to do this job better than you can, but I’m going to let you try. To be sure it’s done right, however, I will leave you detailed instructions for every individual task. And when I travel, I will call in every couple of hours to make sure you are following those instructions to the letter.”

Most women would complain immediately to human resources and perhaps start considering a lawsuit. But when I describe this hypothetical scene to audiences of women, the laughter begins to ripple along the rows by the time I get to “I will leave you detailed instructions.” This is precisely the way the majority of us treat our husbands or male partners when we leave them in charge of the children. When I point out our own double standards in this regard, double standards we have long ago fiercely rejected in the workplace, I see a number of women looking slightly shamefaced. But inevitably at least one woman in the audience will raise her hand and say what many others are thinking: “But they really don’t know how to do it.”

“Do you have any idea what the house would look like if I weren’t there?”

“My husband would feed them pizza every night.”

I laugh and agree. But then I point out that I have spent many years in my career wondering why men seem to think that their way of getting work done is the best or only way. The cult of face time; the endless sports metaphors; the assumption that bigger is (almost) always better. I often have a different way of doing things, and who are my male colleagues to say I’m wrong, as long as the work gets done and done well? Women initially had to accept the roles and routines of office work on male terms; increased equality today means that women are increasingly free to do it our way. Why shouldn’t men have that same liberty and equality at home?

Men are certainly aware of a widespread female presumption that we really do know better when it comes to home and kids. In an article in New York magazine, therapist Barbara Kass calls many of us out on this account: “So many women want to control their husbands’ parenting. ‘Oh, do you have the this? Did you do the that? Don’t forget that she needs this. And make sure she naps.’ Sexism is internalized.” On Huffington Post, dad blogger Aaron Gouveia notes it’s mostly the moms “who claim to be over- worked and desperate for dads to do more” who also criticize dads for not doing things right when they do step up. “And by right, I mean their way. I’ve seen dads criticized and made fun of for how they dress the baby [and] for how they feed the baby.”

Still, for the sake of argument, let’s assume for the moment that the average woman you know is better at managing all the household tasks and childcare than the average man. Now ask yourself why that might be so. Both practice and confidence come to mind.

In families with biological children, the mother bears the child and typically breastfeeds. That means she instantly begins gaining competence, even if at first she’s having a whole new experience. Confidence—or lack of confidence— are self-fulfilling prophecies, as we know from social psychologist Claude Steele’s work on priming. In Whistling Vivaldi, he discusses how stereotypes can be both cultural and situational. For example, women, blacks, and Latinos are told they are bad at math, and so they don’t do as well in math overall as Asians and men. But Steele showed that “stereotype threat” can be situational, too. He did a study where researchers told one group of white male Stanford students with high math ability that they were taking a difficult eighteen-question test on which “Asians tend to do better than whites.” A control group of white male students was told nothing. The results were stark. The white men who were told that Asians do better on the test performed three questions worse than the students who were told nothing at all, the difference between an A and a B grade.

If women assume they can do whatever needs to be done in the domestic space better and faster than men can, they are likely to be better. Conversely, as Rutgers professor Stuart Shapiro puts it, “If a man is told repeatedly he is not good at child care (or cooking dinner), or that the family is better off if the woman does more of it, he will probably start believing it (as he is probably predisposed to anyway).”

Once again, biology rears its controversial head here. Women produce big doses of the “love hormone,” oxytocin, during labor, which plays a part in that magic moment when you look into your baby’s face and your world shifts under your feet. Men don’t. Women breast-feed. Men don’t. In nature only 5 percent of male mammals are engaged fathers; the other 95 percent inseminate and depart. Surely then, even if we feminists deny it with our dying breaths, women are “naturally” customized for child rearing.

But not so fast. It is true that women get that dose of oxytocin and that they breast-feed. Neuroscientists Kelly Lambert and Craig Kinsley have shown that motherhood makes rats smarter, more emotionally resilient, and physically agile. It turns out, however, that similar changes, and the same hormones, are found in the brains of male California deer mice, one of the species in which both males and females care for the pups. And deer mice are not the only species in which the male is affected by parenting. Endocrine systems and neural circuitry are altered in a manner “strikingly similar to that in mothers” in male marmosets, owl monkeys, and, of course, human beings.

We are entering a vast new age of knowledge about our brains, our bodies, our biology. What we should assume above all right now is how much we don’t know about what men and women can do and about what we are programmed and conditioned to do by both nature and nurture. Are we different? Of course. But different in ways that constrain our abilities and possibilities as either breadwinners or caregivers? We have no idea.

It’s worth remembering Kelly Lambert’s words of wisdom: “If nature teaches anything, it’s that those species flexible enough to adapt to changing environments are the ones that survive.”

vividly remember the first time one of our sons woke up in the night and called for Daddy instead of Mommy. My first reaction, to put it politely, was deep dismay. I’m his mother. Kids are supposed to call for their mother. If he’s not calling for me, then I must not be a good mom.

vividly remember the first time one of our sons woke up in the night and called for Daddy instead of Mommy. My first reaction, to put it politely, was deep dismay. I’m his mother. Kids are supposed to call for their mother. If he’s not calling for me, then I must not be a good mom.

On that particular occasion, I got up and comforted my son, telling him Mommy was here and that Daddy was sleeping downstairs; all was right with the world. Over the years, on the many other occasions when our sons turned first to my husband Andy rather than to me—for homework help or advice on subjects ranging from music to girls—I have had some tough conversations with myself. Even if, as my mother would say, I have always wanted to have my cake and eat it too, I simply cannot have all the rewards and satisfactions of my career and expect to be the person my sons call for first

I have also reflected on my emotion that night. Was it guilt? That ideal of the good mother as the person who is always there when her kids need her? In the United States, at least, we’ve beaten that subject to death in recent years, asking ourselves repeatedly why the standards of mothering have become so exacting and all-consuming. I have often wondered what happened to the mantra of “benign neglect,” which my mother used to quote as the best guide to child rearing. As one of my friends put it, nowadays “benign neglect would result in someone calling social services.”

In her 2014 bestseller All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenthood, Jennifer Senior points to the confluence of several factors—Americans having fewer children, women having more control over their reproductive lives thanks to widely available contraception, and parents having children later than they did in my mother’s day—as reasons why benign neglect went out of style. From 1970 to 2006, the proportion of women having their first child after the age of thirty-five increased nearly eightfold. “Because so many of us are now avid volunteers for a project in which we were all once dutiful conscripts,” Senior writes, “we have heightened expectations of what children will do for us, regarding them as sources of existential fulfillment rather than as ordinary parts of our lives.”

If I am honest with myself, the hardest emotion to work through when I heard our son call for Andy rather than for me was not guilt but envy. Even with all the rewards of my career, I would still like for them to call for me first. As the psychiatrist Andras Angyal writes, “We ourselves want to be needed. We do not only have needs, we are also strongly motivated by needed-ness.” Mothers have gotten that special rush for years when a child reaches for us and says no one else will do; the question is whether we really want or are willing to share that role with others.

It is still unquestionably important to me that our sons turn to me first on some things; I specialize in emotional issues and moral dilemmas. Overall, however, I have to accept that if I’m going to travel as much as my career often demands, then Andy is going to be the anchor parent at home.

My experience can’t be said to reflect a universal truth. But being needed is a universal desire and the traditional coin in which mothers have been compensated. If we accept that trade-offs are necessary for women if they want to reach the top of their careers, even if they have money and choices, and if we’re prepared to let men be equal caregivers just as we insist on being equal competitors, then we have to be very honest about our deepest needs and desires. It is one thing to let go of the housekeeping. Quite another to relinquish being the center of your children’s universe.

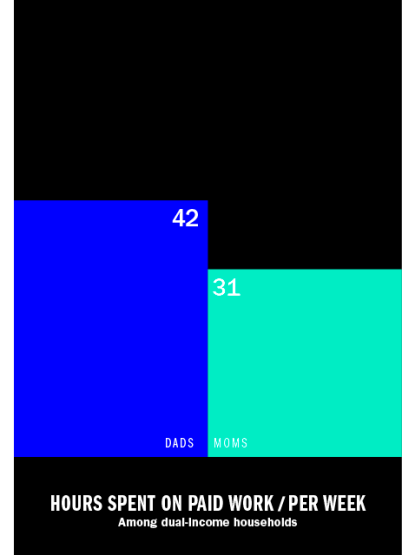

n our stylized accounts of the past, women were homemakers, confident and capable in their own sphere. Men owned the world of work, confident in theirs. Now women are rising fast at work, glorying in their ability to be all the things men used to be and to be just as good or better. A woman who manages to both “bring home the bacon and fry it up,” all while managing a calendar on the fridge that looks like an air traffic control chart, is a superwoman. She may be completely exhausted and less happy than she was forty years ago, but at least she has that.

n our stylized accounts of the past, women were homemakers, confident and capable in their own sphere. Men owned the world of work, confident in theirs. Now women are rising fast at work, glorying in their ability to be all the things men used to be and to be just as good or better. A woman who manages to both “bring home the bacon and fry it up,” all while managing a calendar on the fridge that looks like an air traffic control chart, is a superwoman. She may be completely exhausted and less happy than she was forty years ago, but at least she has that.

We need to step off our new self-created pedestals. When we are feeling overwhelmed, we need to let go and ask for help. It often takes much more strength on our part to acknowledge weakness than to pretend infinite competence.

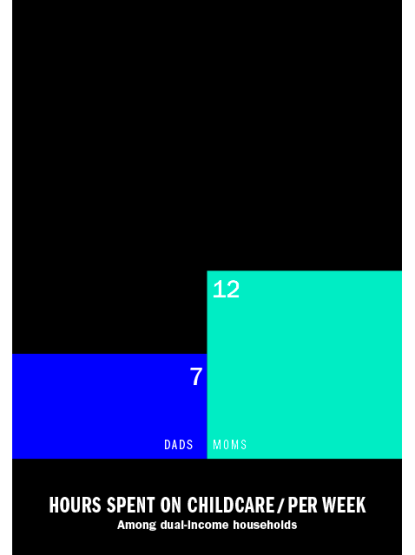

Some readers are probably thinking at this point: Of course! That’s exactly what we have been asking for. We want the men in our lives to pick up the slack, to be equal partners as caregivers so that we can be equal partners as breadwinners.

But that’s exactly the final place we have to let go. We have been asking for “help.” That means we decide what needs to be done and we ask the men in our lives to help us do it. It’s not going to work that way. Real equality means equality at home just as much as at work. It means a whole new domestic order.

It has taken Andy and me a long time to get to this place. For years, I got upset with Andy about why everything domestic seemed to be my responsibility. Although he did lots of stuff, it was almost always when I told him what needed to be done, and he never seemed to feel the urgency or necessity of getting it done himself. But then I came to realize something else: for a long time I wasn’t really willing to let him take responsibility. I did feel, deep down, that I knew what I was doing in terms of running our household better than he did. I didn’t really trust him to be able to do it on his own, or certainly not to do it the way I would.

As our sons would be quick to point out, that’s sexism, plain and simple. I was assuming, like almost all the women I know, that he wouldn’t be able to take care of the kids or run a household as well as I could because he’s a man. But of course if a man were to assume that I really can’t practice law or medicine or business or any other profession or job as well as he can because I’m a woman, I would hit the roof.

So why won’t we let go? At least part of the reason why women assume that we are superior in the home, and that our way of parenting or decorating or homemaking generally is the right way, is the oft-cited mantra that women are better than men at multitasking.

In her controversial article “The Retro Wife,” journalist Lisa Miller writes, “Among my friends, many women behave as though the evolutionary imperative extends not just to birthing and breast-feeding but to administrative household tasks as well, as if only they can properly plan birthday parties, make doctors’ appointments, wrap presents, communicate with the teacher, buy the new school shoes.” She goes on to cite a 2010 British study showing that “men lack the same mental bandwidth for multi-tasking as women. Male and female subjects were asked how they’d find a lost key, while also being given a number of unrelated chores to do—talk on the phone, read a map, complete a math problem. The women universally approached the hunt more efficiently.”

Okay. For the sake of argument, let’s assume that women are better at doing multiple things at once. So what? No matter which partner is better at focusing or multitasking, homework monitoring or organizing playdates, if we women truly want equal partners in the home, then we can’t ask our husbands to be “equal” on our terms. Andy’s view of how to run a household definitely differs from mine, just as his taste in everything from furniture to how to organize a kitchen differs. But why is my way the right way?

And even if every stereotype does hold, and our worst female fears of living rooms turning into man caves are realized, are we really so sure that our kids will come out worse? While single fathers may not be nearly as plentiful as single mothers, they have managed to raise plenty of successful kids. So have families with two dads or two moms. Alternatively, if women let go and let the men in our lives be genuinely equal or primary caregivers, we may just find that all these stereotypes of male/female parenting differences are socialized as well.

There is only one way to find out.

very generation assumes that the way it does things is the way things are. Notions of who should be caregiving and who should be working, for instance, are as historically contingent as notions of who should be allowed to marry each other. Interracial marriage was illegal in many states until 1967; modern British royalty were not allowed to marry commoners until Prince Charles married Diana, or previously divorced spouses until he married Camilla; and the struggle for equality on many levels is still in full swing. In terms of parenting, fathers were often the primary caretakers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. What was once unthinkable in one age becomes normal in another. So try to envision what the future might hold, and how we might get there.

very generation assumes that the way it does things is the way things are. Notions of who should be caregiving and who should be working, for instance, are as historically contingent as notions of who should be allowed to marry each other. Interracial marriage was illegal in many states until 1967; modern British royalty were not allowed to marry commoners until Prince Charles married Diana, or previously divorced spouses until he married Camilla; and the struggle for equality on many levels is still in full swing. In terms of parenting, fathers were often the primary caretakers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. What was once unthinkable in one age becomes normal in another. So try to envision what the future might hold, and how we might get there.

Close your eyes and just imagine letting it all go—the expectations you imagine others have of you and that you have of yourself, your mate, and your house. Imagine that if your children call for your husband or partner or any other loving adult in their lives, then you have the security of knowing that many different people can be there for them. Imagine that your mate takes charge of an equal set of domestic responsibilities and tells you what to do to help out and fill in.

If we can let go of the mountain of assumptions, biases, expectations, double standards, and doubts that so many of us carry around, then a new world of possibilities awaits. We may lose our status as superwomen, but we have everything to gain.

Adapted with permission from Unfinished Business: Women Men Work Family (Random House, September 2015), by Anne-Marie Slaughter.