![]()

In spring 2014, parents in the normally progressive Bay Area city of Fremont, California, started a campaign to get a book removed from the 9th grade curriculum for the five district high schools, arguing it was inappropriate for their 13 and 14-year olds. They hired a local lawyer and put together a petition with more than 2500 signatures.

Their target: Your Health Today, a sex-ed book published by McGraw Hill. It offers the traditional advice and awkward diagrams plus some considerably more modern tips: a how-to for asking partners if they’ve been tested for STDs, a debate on legalizing prostitution. And then there was this: “[One] kind of sex game is bondage and discipline, in which restriction of movement (e.g. using handcuffs or ropes) or sensory deprivation (using blindfolds or masks) is employed for sexual enjoyment. Most sex games are safe and harmless, but partners need to openly discuss and agree beforehand on what they are comfortable doing.”

“I was just astounded,” says Fremont mom Teri Topham. “My daughter is 13. She needs to know how boys feel. I frankly don’t want her debating with other 13-year-olds how well the adult film industry is practicing safe sex.” Another parent, Asfia Ahmed, who has eight and ninth grade boys, adds: “It assumes the audience is already drinking alcohol, already doing drugs, already have multiple sexual partners…Even if they are experimenting at this age, it says atypical sexual behaviors are normal. ”

But school board members contend that 9th grade students have already been exposed to the contents of the book—and much, much more. They argue that even relatively modern sex ed has even not begun to reckon with what kids are now exposed to in person and online.

But school board members contend that 9th grade students have already been exposed to the contents of the book—and much, much more. They argue that even relatively modern sex ed has even not begun to reckon with what kids are now exposed to in person and online.

The singer Rihanna, for example, has legions of young fans. Her music video for the song “S&M”—viewed more than 57 million times on YouTube so far—shows the artist, pig-tied and writhing, cooing “chains and whips excite me.” It then cuts to her using a whip on men and women with mouths covered in duct tape.

“I think denying that [sex] is part of our culture in 2014 is really not serving our kids well,” says Lara Calvert-York, president of the Fremont school board, who argues that kids are already seeing hyper-sexualized content—on after school TV. “So, let’s have a frank conversation about what these things are if that’s what the kids need to talk about,” she says. “And let’s do it in classroom setting, with highly qualified, credentialed teachers, who know how to have those conversations. Because a lot of parents don’t know how to have that conversation when they’re sitting next to their kids and it comes up in a TV show. Everyone is feeling a little awkward.”

But the Fremont parents aren’t budging. “Any good parent monitors what their child has access to,” says Topham. “We don’t say, ‘they’re going to drink anyway, let’s give them a car with bigger airbags.’” The parents note that the book was actually written for college students, and refers to college-related activities like bar crawls. (While acknowledging this, the book’s author Sara L. C. Mackenzie, believes it’s appropriate for high schoolers; her children read it at 13.)

The book has been shelved, at least for this year. But the problem isn’t going away. The Fremont showdown is a local skirmish in what has become a complicated and exhausting battle that schools and parents are facing across the nation. How, when, and what to tell kids about sex today? TIME reviewed the leading research on the subject as well as currently available resources to produce the information that follows, as well as specific guides to how and when to talk to kids on individual topics.

(Read more: How—and when—to talk your kids about which subjects.)

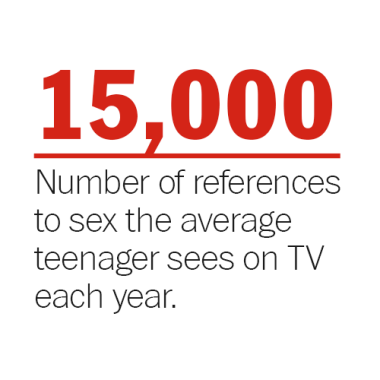

The average American young person spends over seven hours a day on media devices, often using multiple systems at once. Studies show that more than 75% of primetime TV programs contain sexual content, and the mention of sex on TV can occur up to eight to 10 times in a single hour. And that’s the soft stuff: A national sample study of 1,500 10 to 17-year-olds showed that about half of those that use the Internet had been exposed to online porn in the last year.

How do you learn appropriateness and consent in a culture where Beyoncé’s song about pleasuring a guy in a car is championed by some as feminist and others as lewd? Or where Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” can refer to violent sexual acts in a music video viewed on the web at least 36 million times? Or where, in a major news story, it becomes apparent that wholesome girls from teen adventure movies send naked photos. Or where primetime TV shows—the kind you often watch with your family—not infrequently make reference to anal sex?

Uncensored media is not harmless. Longitudinal studies suggest exposure to sexual content on TV and other media in early adolescence is linked to double the risk of early sexual intercourse, and young people whose parents limit their TV time are less likely to partake in early sexual behavior. Other studies have found that 10% of young women who had their first sexual experience in their teenage years say it was not their choice, and the younger they were, the more likely this was the case. While the vast majority of primetime programming contains sexual content, only 14% of sexual incidents mention the risks or responsibilities associated with sexual activity according to research from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Uncensored media is not harmless. Longitudinal studies suggest exposure to sexual content on TV and other media in early adolescence is linked to double the risk of early sexual intercourse, and young people whose parents limit their TV time are less likely to partake in early sexual behavior. Other studies have found that 10% of young women who had their first sexual experience in their teenage years say it was not their choice, and the younger they were, the more likely this was the case. While the vast majority of primetime programming contains sexual content, only 14% of sexual incidents mention the risks or responsibilities associated with sexual activity according to research from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

And that’s just the media teenagers consume. There’s a whole different set of issues raised by the other ways they use tools of communication.

“I was sexting and sending pictures to a guy older than me because he told me he loved me and i believed him and he showed everyone my picture and i had everyone asking me for photos and making fun of me and calling me a slut.”

“me n my girlfriend have been datin a year an almost 2months, she has sent me naked pics of her and she asked me to send her some of me naked, but i dont want too and i dont want to lose her either.”

“My girlfriend will text me good morning, if i dont respond right away she will send a question mark with a question, then a few more question marks, then call me. If i don’t respond she gets realy upset and angry. is this abuse? what do i do?”

Young people now engage in relationships increasingly via technology, which means they’re able to connect in a variety of ways and at a speed and frequency not known to prior generations. They also appear to be more comfortable showing skin. A 2014 survey published in the journal Pediatrics among over 1,000 early middle school students found 20% reporting receiving sexually explicit cell phone text or picture messages (more colloquially known as “sexts”) and 5% reporting sending them.

While many parents think that explaining the consequences of sending out explicit images will get teens to stop, they may be missing the point. “There’s a pressure that people feel to send a sext as a digital currency of trust,” says Emily Weinstein a Harvard University doctoral student who collected the texts above from an online forum run by MTV, for a study on the digital stress of adolescence. “It’s a way to say to someone, here is a thing that could destroy me, I trust that you won’t use it.”

On paper, the United States is checking all the right boxes of managing teen sexual behavior. The national pregnancy rate is at a record low and it appears teens are waiting longer to have sex, and those that are sexually active are using birth control more than previous years. But these numbers only tell a tiny snippet of the story.

“Sex education in the U.S. has only gotten worse,” says Victor Strasburger, an adolescent medicine expert and distinguished professor of pediatrics at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine. “Most of the time they don’t talk about contraception, they don’t talk about risk of pregnancy, STIs [sexually transmitted infections]—certainly not abortion. At some point you would think adults would come to their senses and say hey we have to counteract this.”

(Read more: Sex Education, From ‘Social Hygiene’ to ‘The Porn Factor’)

Strasburger says the U.S. shouldn’t base success on its teen pregnancy numbers: “Everyone else’s teen pregnancy rate has gone down too. Before we pat ourselves on the back, we should acknowledge that we still have the highest rate in the Western World.”

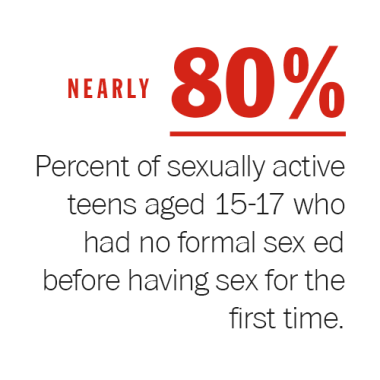

Not only does sex education still virtually not exist in some areas of the country, but school programs that do teach kids about what used to be called the facts of life start too late. A recent CDC study showed that among teens ages 15-17 who have had sex, nearly 80% did not receive any formal sex education before they lost their virginity. Or, if they did, it was only to discourage them from being sexually active. “Parents and legislators fail to understand that although they may favor abstinence-only sex education (despite the lack of any evidence of its effectiveness), the media are decidedly not abstinence only,” reads a 2010 American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement.

“I had sex with my older boyfriend at 16,” says Ashley Jones, 22, a young Georgia woman. “Suddenly my dad wanted to talk about the birds and the bees. I was like, what? It’s too late!” (The Kinsey institute puts the average age that kids have first have sex at 16.9 for boys and 17.4 for girls.)

Current sex education, where it does exist, often teaches the basic plumbing, but it’s not answering the questions young people really have when it comes to sexuality: What should I do when my girlfriend/boyfriend is pressuring me to have sex? What on earth was happening in that video I probably shouldn’t have clicked online? What do I do when my best friend tells me they’re gay—or I think I am?

School-wide sex education largely ignores gay men and women. “I think the Internet is one of the most commonly used sources for young LGBT folks to gain information,” says Adrian Nava, 19, who says his question about same sex relationships in his Colorado high school sex ed class that was shot down by the teacher. “In some ways it’s great because online forums tend to be supportive and positive. But there’s so much misinformation that reinforces negative feelings.”

(Read more: How to Talk to Your Gay Teen About Sex)

Sex ed courses tends to hyper-focus on the girls. “Girls are the ones who have babies,” says Victoria Jennings, director of the Institute for Reproductive Health at Georgetown University, whose research has shown there are globally more programs developed to help young girls navigate their sexuality than to help boys. Given the fact that recent CDC literature shows 43.9% of women have experienced some form of unwanted sexual violence that was not rape, and 23.4% of men have experienced the same, public health experts agree both sexes need education on appropriate behavior.

It doesn’t help that the two groups are getting quite different messages. “The way we talk to boys is antiquated and stereotypical,” says Rosalind Wiseman, educator and author of Queen Bees and Wannabes, about teen girls and Masterminds and Wingmen, on boys. “There’s an assumption that they’re insensitive, sex-crazed, hormone-crazed. It’s no surprise that so many boys disengage from so many conversations about sex ed.”

We teach girls how to protect themselves, adds Wiseman, and their rights to say yes and no to sexual behaviors. But we don’t teach boys the complexities of these situations or that they’re a part of the conversation. “We talk to them in sound bites: ‘no means no.’ Well, of course it does, but it’s really confusing when you’re a 15-year-old boy and you’re interacting with girls that are trying out their sexuality,” she adds. Data show that boys are less likely than girls to talk to their parents about birth control or “how to say no to sex,” and 46% of sexually experienced teen boys do not receive formal instruction about contraception before they first have sex compared to 33% of teen girls.

Yet completely reshaping the sex education landscape is currently almost impossible, not just because of disagreements like the one in Fremont, but because schools lack resources. There’s historically large funding for abstinence-only education, but supporters of comprehensive sex education—which deals with contraception, sexually transmitted diseases and relationships—face significant logistical and financial barriers.

Only 22 states and the District of Columbia require public schools teach sex education. Oklahoma and Alabama—two states with the highest teen pregnancy rates—don’t require any sex ed. And few states really take a critical look at sexuality in the way kids encounter it, through TV shows, movies, and yes, even pornography. It’s like taking a child to a waterpark without teaching them how to swim.

This leaves the ball in the parents’ court. A recent survey from Planned Parenthood shows that 80% of parents are willing to have “the talk” with their kids, but in order for these conversations to have real meaning, parents need to understand just how much sexual exposure their kids are getting daily and how soon. They also need to overcome the desire to lecture, and kids need to understand that the conversation is less about rules and more about guidance. All of this while having a conversation about what is usually a very private matter.

Some experts believe that many of the obstacles can be overcome by approaching the adolescent in his or her own habitat: using the Internet or cell phones as learning tools.

“Perhaps it’s time to fully embrace the power of 21st century communication and direct it toward public health goals more deliberately,” wrote Strasburger and Sarah Brown, the CEO of The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, in a July report. “Online material and social media could help to fill the gaps in sex education and support for many young people.”

“Perhaps it’s time to fully embrace the power of 21st century communication and direct it toward public health goals more deliberately,” wrote Strasburger and Sarah Brown, the CEO of The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, in a July report. “Online material and social media could help to fill the gaps in sex education and support for many young people.”

Websites like Bedsider.org (developed by Brown’s group) offer easy to understand facts about contraception in an open-minded and legitimate way. As do other websites like StayTeen.org, GoAskAlice! and Sex, etc. On Scarleteen.com, educators answer questions from “How do I behave sexually without someone thinking I’m a slut?” to questions about pubic hair.

For reaching teenagers right where they gather, it’s hard to beat YouTube. Laci Green has made a name for herself by providing frank and funny videos that answer common questions young people have and dispel myths. Her approach is not for everyone; two of her more popular episodes are “You Can’t POP Your Cherry! (Hymen 101)” and “Sex Object BS.”

Texting has also proved to be a surprisingly useful tool. Some health departments and community groups in states like California and North Carolina have established services where teens can text their sex-related questions to a number and receive a texted response in 24 hours, allowing for anonymity. Planned Parenthood offers a chat/text program where teens and young adults can either live text or chat with a Planned Parenthood staffer. Since the launch in May this year, there have been a total of 393,174 conversations.

Should parents really cede sex education to the digital realm? Given that an incredibly high number of young people go to the Internet for information on sex anyway, directing them to quality material that appeals to their age range may be the one of the better ways to circumvent poor education at school. Showing kids a reliable website can’t replace a good conversation, but it can complement one.

In Fremont, parents are supplementing their children’s sex education in different ways. “I don’t just rely on the school to teach sex ed to my children,” says Topham. “I told my kids about [sex] when they are in third grade, and open up the dialogue at that point. When we are watching movies together or discussing current events that may touch on this topic, we talk about it.”

Not all parents are prepared to go as far as Topham: Her five kids did not get a smartphone until they were 18 and they can’t have TVs or computers in their bedrooms. “You can be the best kid possible but we don’t want you to have porn in your pocket,” she says. To some her views may seem extreme, but when it comes to sex ed, Topham’s decided it’s better to take no chances. In the age of Innocence vs. the Internet, some parents won’t go down without a fight.

![]()

More than 100 years of trying to teach kids the facts of life

![]()

![]()

Advice from Dannielle Owens-Reid and Kristin Russo, co-authors of This Is a Book For Parents of Gay Kids

I never learned how to have safe sex. I am sure that I had a few health classes that talked about condoms and rattled off a lot of facts about scary diseases I might get if I did the wrong thing with the wrong person—but no one ever mentioned what to do if I wasn’t having sex with a boy. I didn’t know if I was supposed to protect myself and, if I was, I had never heard of any ways in which I could do so. My parents didn’t know that I was gay until after I was sexually active, and I don’t think they ever even considered talking to me about having safe “gay” sex. —Kristin

If your kid has recently come out to you as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer, there is a chance that you might feel a bit like a deer in headlights when it comes to approaching them with tips on safe sex. Between 1991 and 2010, the average age of coming out dropped dramatically from 25 to 16, which means many young people are already out by the time parents would start talking with them about sex.

Finding out how to talk to your LGBTQ kid about safe sex is much, much easier than you think. The more you know, the more open you can be with your child and the more open you can be about sex, the easier it becomes for your kid to talk to you about their questions and concerns. Here are the three main points to remember:

Be Open to Questions

The earlier you start talking to your kids, the easier things will be for you later in the game, according to globally recognized sex expert Dr. Justine Shuey. “The most important thing you can accomplish is to become an askable parent,” she says. This does not mean you have to have all of the answers, or that you need to be comfortable talking to your child about everything (or telling them what you do sexually) — just that you are approachable. If you don’t know an answer, research it together, or look for reliable and factually accurate sources with your child.

“When I teach educators, I teach them to first say ‘Good question,’ ” Shuey explains. “That is your moment to think about your answer before you laugh or blurt out something silly or negative.”

Educate Yourself

Before you start looking for resources to answer your questions, it’s helpful to address the many misconceptions surrounding the LGBTQ community. First, your child isn’t going to have any more sex than their classmates — our identities do not shape our personalities or our interest in sex. Second, they face the same risks; fluids are fluids are fluids, and sexually transmitted infections can happen to any sexually active human being on this planet.

Lastly, there’s no such thing as “gay” sex acts—there are sexual acts that are shared between people of all genders, and the way we keep ourselves safe is always the same. Inform yourself about ways to be safe when engaging in oral sex, anal sex and sex with toys. Newsflash: these are sexual acts that any person may engage in, so even if your kid doesn’t identify as LGBT, they still need to be informed.

Learn What Works for Your Kid

We all have our own relationships to sex, and we also all have our own relationships to our children. You know your kid, and you also know yourself, so don’t feel as though there’s only one way to exchange this important information. The “sex talk” doesn’t—and most likely shouldn’t—have to be one long conversation held at the dinner table. It can be something that evolves over time, perhaps in a letter or over the course of several smaller discussions. Prepare yourself with information, and communicate in the way that you think will bring the highest level of comfort to both you and your child.

Sometimes that means having a talk without actually talking. Oluremi, an out 18-year-old whom we spoke to while researching our book, said her mother took a different route than most when approaching safe sex.

“Luckily, my mom understood that I wasn’t really one for talking, but knew I would read anything put in front of me,” she said. Oluremi’s mom communicated most of her thoughts on safe sex with her daughter through e-mail, which she knew would make the exchange of information easier.

Just like Oluremi’s mom, you can send your kid an email if that’s easier. Or hand them a copy of This is a Book for Parents of Gay Kids with the safe sex chapter bookmarked (shameless plug alert!). Or talk to them about your feelings on sex as much as you are both comfortable and then tell them to check out some of the websites listed in the main story. You can even make them read this article. The point is, you have options in how you approach this topic with your kid.

When all is said and done, familiarizing yourself with the resources available and making them available to your kid is the critical piece of this sex-talk puzzle. Be prepared in case your kid does feel comfortable enough to ask you questions, even if that means just knowing where to point them when you don’t have the answers. Many teens say that they listen to their parents more than anyone else when it comes to practicing safe sex. What you say matters, and what you don’t say can matter even more.

![]()

How to talk to your kids about sex, intimacy and other awkward subjects. Plus reliable, relatable sites to send them for more information.

What kids should know at what age: As a parent, it can be tricky to know when to have The Talk, and how much you should bring up to your kids at what time. The National Sexuality Education Standards suggests that by the end of second grade, kids should know the proper names for male and female body parts and know that all people have the right to tell others not to touch their body when they don’t want to be touched. By the end of fifth grade, they should be able to define the process of human reproduction, and be able to describe puberty and how friends, family, media, society and culture can influence ideas about body image. By the end of eighth grade, kids should be able to explain the health benefits, risks and effectiveness rates of various methods or contraception, including abstinence and condoms and should know how alcohol and drugs can influence sexual decisions. By the end of 12th grade, students should know how to communicate decisions about whether and when to engage in sexual behaviors and understand why using tricks, threats or coercion in a relationship is wrong. (For more detailed information, click on the NSES link above.)

Other useful and reliable websites:

For Parents

Common Sense Media

When it comes to advice and resources for healthy media and technology consumption, Common Sense Media is a one-stop shop. Parents can use the organization’s media reviews tool to look up movies, apps, TV shows, books and games and view a content breakdown of specific elements like violence, language, substance abuse, role models and sex. There are also resources to answer parental concerns related to themes like cyberbullying and social media use. For instance: “How can I help my kid avoid digital drama.”

Answer

Answer is a national organization established by the New Jersey Network for Family Life Education to offer sex ed resources to parents, teens, and advocacy groups. It publishes Sex, Etc. magazine and has a website for teens, written by teens. Especially helpful is Answer’s curated book list, organized by age appropriateness.

Planned Parenthood Federation of America

Planned Parenthood wants parents be the go-to resources for their kids and teens. The site offers advice for how to talk to young people about sex and sexuality, how to parent teens who may be sexually active, and even how to answer questions from LGBT children and teens. Planned Parenthood also offers book lists for both parents and children.

The Guttmacher Institute

For parents who are curious about trends, and want the latest data on issues like contraceptives, puberty and sexual initiation, the Guttmacher Institute offers a scholarly approach on research, education, and police. It publishes two peer-reviewed journals and collects data on topics like adolescents, contraceptives, abortion and STIs.

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy

The National Campaign’s goal is to prevent teen and unplanned pregnancy, especially among single, young adults. The site offers resources to parents and runs several spin off websites like StayTeen.org and Bedsider.org that target young people at different ages and stages in their sexuality.

The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)

SIECUS educates and advocates for better sex ed in the United States. Along with other groups that advocate comprehensive sex ed, it developed “The Future of Sex Education,” an initiative to spur discussion about the future of sex education and to encourage implementing comprehensive sexuality education in public schools.

Sexual Health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

For the most frank and up to date information about sexual health, check out the CDC’s resources on all topics from sexual violence prevention to healthy pregnancies.

For Kids

KidsHealth

Developed by the Nemours Foundation, a non-profit organization focused on children’s health, the site provides health resources for parents, kids and teens. The kids’ site has information about topics like puberty as well as explainers on how all parts of the body work, from the brain to the kidney.

It’s My Life

Run by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, It’s My Life provides kid-friendly information on everything from dating to puberty to eating disorders and money. The site also offers games that help kids navigate issues like gossiping and cheating on school work.

For Teens

Bedsider

Bedsider is an online birth control support network for women 18-29. The site talks to teens like a best friend, and prides itself on being unbiased: It’s not funded by pharmaceutical companies or the government.

Answer

(see above) Answer’s Sex, Etc. magazine and website offer teens advice about gender and talking to parents about sex, plus forums where Answer’s experts answer questions.

Stay Teen

The goal of Stay Teen, a site sponsored by the nonprofit organization National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, is to encourage young people to enjoy their teen years and avoid the responsibilities that come with a too-early pregnancy. It provides resources and advice for how to say no to situations young people are not ready for.

Planned Parenthood

Planned Parenthood has easy to use chat and text sex education programs that allow young people to chat in realtime with a Planned Parenthood staffer about everything from STD to morning-after pill question. The organization also has an Awkward or Not app that takes young people through an online quiz that gives them the chance to send their parents a text to start a conversation about dating and sex.

Go Ask Alice!

Go Ask Alice! is the health question and answer site produced by Alice! Health Promotion at Columbia University. Users can get answers to their questions from how to use a condom properly to urinary problems.

I Wanna Know

Run by the American Sexual Health Association (ASHA), I Wanna Know offers sexual health information for teens and young adults. There’s in-depth information on topics like STDs, relationships and myths. Common Sense says I Wanna Know is appropriate for ages 13 and up.

Laci Green

Laci Green is a sexual health educator who creates fun and flashy videos to answer sex-related questions people are often too embarrassed to ask. Green has over one million subscribers to her YouTube channel. Her content is fun, but some parents may find it too explicit.

Scarleteen

Scarleteen is an edgy site that provides sexuality education through popular message boards and fact sheets. Data has shown young people spend almost twice as long on the site as THE AVERAGE user DOES on Facebook. It’s also more explicit than OTHER sexual health sites, but answers questions submitted by teenagers themselves. All message boards are moderated by Scarleteen staff and volunteers.

Center for Young Women’s Health

Young women looking for easy-to-access accurate and extensive information about all sexual and gynecological health topics can find it at the Center for Young Women’s Health. The center is developed as a partnership between the Division of Adolescent & Young Adult Medicine, the Division of Gynecology, and the Center for Congenital Anomalies of the Reproductive Tract at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Young Men’s Health

Youngmenshealthsite.org (YMH) is produced by the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital. The site provides well-researched health information to teen boys and young men. There’s sexual health information as well as explainers on other health issues from celiac disease to Ebola.

Advocates for Youth

Advocated for Youth is an organization meant to help young people make informed and responsible decisions about their reproductive and sexual health. The organization also offers support to young people who want to bring better sex education to their schools.