It’s one thing to be elected President of the U.S. Learning how to do the job usually takes longer

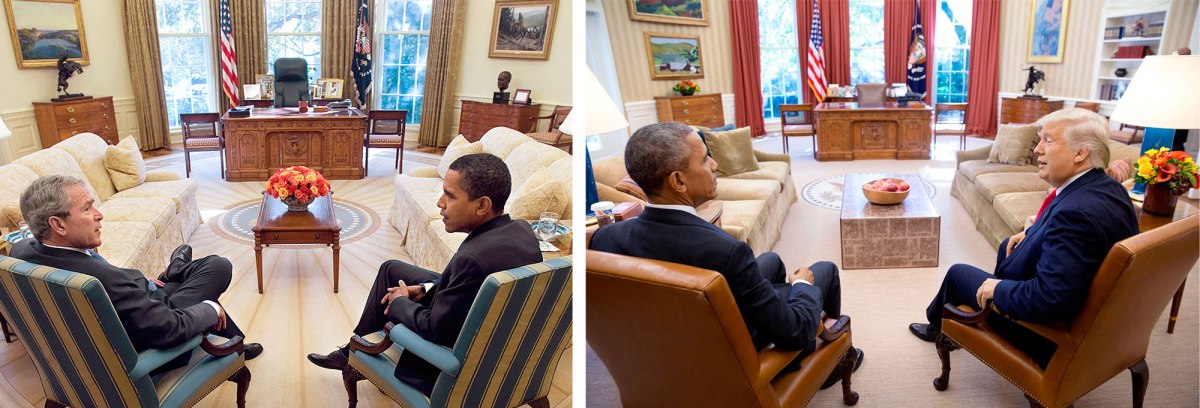

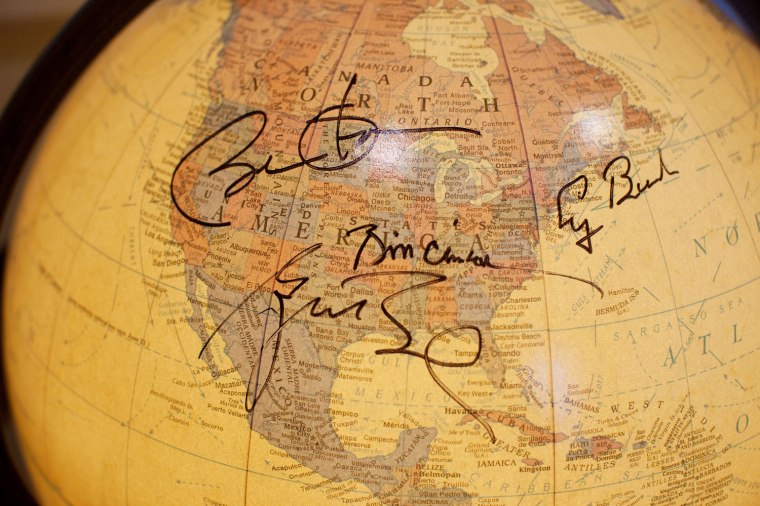

A Presidential handoff comes with established rites and rituals, some political, others personal, all a measure of the weight bearing down on the rising leader of the free world: a meeting (or meetings) between incoming and outgoing Presidents, a summit for their lieutenants and Cabinet officers, that first glimpse into the secret compartments of national security and the fearsome threats abounding, the tour of the living quarters by the First Ladies, a conversation about the kids. Eight years ago, when George W. Bush hosted a White House welcome lunch for President-elect Barack Obama and all the living former Presidents, some of the talk was about the economy and al-Qaeda, but much was about how you raise a family in the world’s most turbulent fishbowl. These sessions aren’t required by law, but everyone seems to appreciate the help.

Since Donald Trump’s race for the White House was one long, looping detour from convention, it’s natural that the final lap has veered off road as well. Even veterans eager to help him find themselves challenged not just by his unfamiliarity with the ways of Washington but also by his indifference to them. Whether it’s his disdain of intelligence analysts, his distance from his party’s agenda, his Twitter torture of corporations or his defiant and diversionary Jan. 11 press conference, everything about the Trump transition has tested the machinery of power and protocol. This suggests that the weeks to come will involve a steep learning curve not just for the new Commander in Chief but for the rest of us as well. In his farewell address on Jan. 10, Obama had to stop and quiet those in his crowd who booed his promise to ensure a smooth transition of power to Trump. He called the cooperation a “hallmark of our democracy,” running deeper than his disagreements with the man who will replace him. “Just as President Bush did for me,” Obama said.

In the pages that follow, veterans of the Obama White House offer their own counsel to the incoming team—including some of the best advice they got from the departing Bush team eight years ago. They cover everything from distinguishing what’s important from what’s merely urgent, to managing your health, mastering the computers and navigating the White House mess (closed between 2 p.m. and 3 p.m., so stagger your coffee runs). It’s unusual to move into a new workspace with nearly 100% turnover, with the incoming team just meeting one another for the first time under the bright glare of the international spotlight.

There is no predicting the impact any of this will have on the actions and attitude of a newly inaugurated President Trump. Even he has shown some surprise at adopting his new identity, starting with his Oval Office meeting with Obama two days after his victory. “I will tell you, I really liked him, I think he liked me,” Trump told TIME a few weeks later. “I think he was surprised also. There was good chemistry.”

That this followed a brutal campaign in which he had called Obama “the worst President” and Obama called Trump “unfit to serve” is not actually unusual, judging from past presidential handoffs. On the one hand, Obama has principles to defend in the face of an incoming President who has vowed to dismember Obamacare, trade treaties and environmental guardrails. It recalls Ronald Reagan ordering Jimmy Carter’s solar panels removed from the roof, or John F. Kennedy dismantling Eisenhower’s national-security structure. Any outgoing President is mindful of his legacy. Any new President arrives thinking he knows better, with millions of votes—even if not a majority—in his pocket to affirm his sense of mission.

But Obama also leaves office all too aware of the burdens that are about to shift from his shoulders. Eight years ago, at that gathering of Presidents, George W. Bush had said to him, “We want you to succeed.” At that moment, party no longer mattered. “All of us who have served in this office understand that the office transcends the individual.”

Obama has honored that tradition in his conversations in person and by phone with Trump. “The main thing that I’ve tried to transmit is that there’s a difference between governing and campaigning, so that what he has to appreciate is as soon as you walk into this office after you’ve been sworn in, you’re now in charge of the largest organization on earth,” he told ABC’s George Stephanopoulos. “You can’t manage it the way you would manage a family business.”

That Trump had never held elective office of any kind proved a significant asset to him throughout the campaign: no voting record to haunt him, few political debts to repay, no habit of speaking without saying something. But there is little precedent for Washington generally—and the White House particularly—to absorb such an alien, and often actively hostile, outsider. The closest parallel is Eisenhower taking over from Harry Truman in 1953, also his first time in elective office. But Ike had spent years navigating the secret warrens of the capital in his role as Supreme Allied Commander and Army Chief of Staff.

Truman imagined just how hard Eisenhower’s evolution would be. “He’ll sit here, and he’ll say, ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen,” Truman observed. “Poor Ike—it won’t be a bit like the Army. He’ll find it very frustrating.” Or as Trump might put it in a tweet—“SAD!” Obama’s experience before the Oval Office was also thin by modern standards—three terms in the Illinois state senate, barely four years in D.C. But he entered office with one advantage over Trump: a 68% approval rating in January 2009, compared with Trump’s 43%.

Trump will find the place pretty well fenced in. It’s a supreme irony that the leader of the free world has precious little personal freedom. At 18 acres, the White House complex is one acre larger than Mar-a-Lago, but security makes it feel smaller. Hillary Clinton could have told him how as First Lady she used to slip out of the White House in disguise and take long walks with a lone Secret Service agent, up Connecticut Avenue to the National Zoo, just to escape. These are buildings where even the trash isn’t so much collected as sorted because nearly everything, every record, memo, email, is saved for posterity. Which means that a man who avoids computers and still conceals his tax returns will live in a world where transparency is etched into law.

It may turn out that Trump never fully settles into Washington and spends much of his term commuting from Palm Beach or ruling from his Fifth Avenue Olympus, slipping into Washington for state visits and such a few days a week. He has already demonstrated his willingness to negotiate with Congress in full view, via 140-character bursts.

“I remember what it was like when I came in eight years ago,” Obama said after his meeting with Trump. “It is a big challenge. This office is bigger than any one person, and that’s why ensuring a smooth transition is so important. It’s not something that the Constitution explicitly requires, but it is one of those norms that are vital to a functioning democracy, similar to norms of civility and tolerance and a commitment to reason and facts and analysis.”

At a time of deep division and disagreement, the nation can take comfort that this particular unifying spirit persists, as the following pages attest. Let’s hope it’s contagious.

Eighteen current and former Obama aides offer words of advice for their Trump Administration replacements

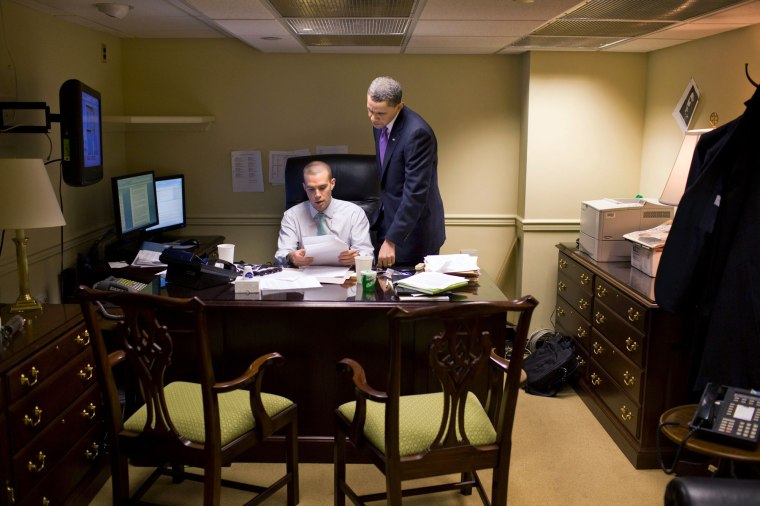

PFEIFFER: Most people don’t understand how the actual handover of power works. We all sit in the freezing cold. We watch the final culmination of years of effort to see our friend and boss become President of the United States. Then for the senior team, you get on a bus and they take you to the White House. They drop you off, and someone shows you your office. You walk in and there’s a computer there with a Post-it note with your password, and you’re in charge of the government. Full stop.

EARNEST: You literally don’t know how anything works. At the night after the second full day, the President and First Lady hosted a staff party for people who had worked on the transition, the campaign and the Inaugural Committee. I missed almost the entire party because I was still in the Lower Press Office figuring out how the next day we were going to send a video link to the weekly address.

PSAKI: None of us knew where the bathroom was. I still didn’t know there was one on the first floor until probably the second year I was here. It may have been the first day, when the President came out of the Oval and walked over into the Upper Press area to see Robert Gibbs in the press secretary’s office, and a number of reporters were streaming out. He said, “Oh wait, they can come over here?” He wasn’t aware of how everything was set up.

VIETOR: For the communications team, especially the staff in Lower Press, you realize that you’re basically going to be working inside the White House press corps’ newsroom. The briefing-room door is almost always open. It’s hard to have a confidential conversation when there are a dozen reporters standing in your office. But ultimately this is a good thing. Dealing with reporters face-to-face will lead to better relationships. You’ll better understand each other as human beings.

BROWN: I remember the President, by accident, walking into my office on Day Two, because he didn’t even know his way around yet.

ABRAHAM: You watch depictions of the building in TV or movies, and one notable TV show in particular. There are these long, winding conversations over long hallways. You get in the building and it’s actually pretty small, pretty crowded. You can’t really say much more than your name and where you’re from before you hit a door.

FURMAN:In terms of figuring out who would be in what office, we looked at the floor plan, and we had a plan to put both of National Economic Council director Larry Summers’ domestic deputies in the West Wing. Then we actually got to the West Wing, looked around and discovered that one of the two rooms we had thought was an office was actually a foyer to the women’s bathroom. That particular seating arrangement ended up not surviving.

DEESE: For the first couple of days, I was literally squatting in a hallway in the second floor of the West Wing.

FURMAN: We also saw that people’s names were taped to the doors. There was a brief moment when the offices right across the hall from ours looked a lot better than ours, and we thought maybe we would just move the taped names and see if we could get away with it. But we decided that that probably wouldn’t be the best way to ingratiate ourselves with our new colleagues.

MCCORMICK LELYVELD: We got to the White House, and the First Lady called us all into the East Room. There in a big circle was the resident staff, ushers, chefs and pastry chefs, and many other team members. She said, “This is the team I came in with,” referring to us. “This is the team that’s in place here, and they’re in charge now. They know the ins and outs. They know the history. It’s our responsibility to defer to them and ask them questions and follow their leadership.” We really just kind of went in concentric circles where we went in one direction to greet everybody and worked around the room.

PHILLIPS: Close your eyes and imagine the physical space at the campaign—one giant room. Desks and people collaborating throughout the day. Fast-forward to the White House and the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. It is a series of compartments. It’s almost like a catacomb. What we ended up doing was actually taking our team, we started around 12 or 13, and jamming them all into large rooms, so we could kind of replicate the experience from the campaign.

JARRETT: We had a computer on our desk. We didn’t have laptops, we didn’t have iPads, we didn’t have iPhones, and we had about a half a bar of service. So if you brought in your own equipment, you couldn’t use it. And that was surprising. I really did think the building would be state-of-the-art, and it was not. It was a big hindrance to our effectiveness early on.

KEENAN: We had Compaqs running Windows 98 or 2000. No laptops. It was like we had gone back in time.

PHILLIPS: All the tools you used to use—whether that’s chat or Google Docs or wi-fi—are no longer available. It’s like a time machine back to sort of a pre-social-media, postcomputer moment, where you just work on email.

EARNEST: The stakes are really high. You may recall that in the first couple of months, there was a day when our email system stopped functioning. This was network news. It was just a reminder to everyone in our office that people are paying very close attention to how well things are running. There’s a lot of pressure to demonstrate to the public that you’re up to the task, even though you are literally pulling the levers of something while you’re still trying to figure out how it works.

ABRAHAM: You’re literally frantically looking at the guy next to you, like, “Hey Gary, how the heck does the printer work? Does anyone have any idea how to order food? Does anyone have any idea?”

RHODES: You realize that it’s just the people in those offices. There is nobody else there. You are responsible. I remember being overwhelmed at first, but then I had the next speech to write and the next meeting to go to. You kind of begin to work your way into the job.

PFEIFFER: I think the most important piece of advice that I would give anyone who’s entering the White House after serving on a winning presidential campaign is that campaigns are AA baseball, and the White House is the major leagues. You’re not as smart as you think you are. Pitches come faster. Be as humble as you possibly can, because you’re going to learn pretty quickly that the stakes are different and the complexity of the decisionmaking is different. Even though you know that going in you’ve seen The West Wing, until you get there and realize the consequences of the things happening around you, it’s pretty hard to fathom.

EMANUEL: I used to tell this to Clinton, but I also used to say it to President Obama: “If we all knew, in the first year of the first term, what we knew by the first year of the second term, we’d be geniuses.” There’s a learning curve. It’s just new.

SUTPHEN: The sheer magnitude of the issue set means that you never have enough time in the day. My meetings were typically in 20-minute increments starting at 8 o’clock and going until 7:30 at night. At the beginning, I used to book myself very tightly during the day. But then I quickly realized, if you do have a crisis, it blows up your whole day. It’s a little bit like Amtrak. The train can be delayed, and then they start canceling. It has this cascading effect if you’re not careful. I created a little bit of room in the morning, just after the meetings, to try to account for things that may have happened overnight.

BROWN: Over time working with the President, I learned there are a bunch of routine things he didn’t actually have to sign. I could use the autopen, but I needed to work with him so that he knew I was never exercising my authority beyond my bounds. I never wanted to do anything without his consent. It turns out that there are a bunch of routine things that once you said, “O.K., here’s a bucket of things,” he can say, “That’s fine, you do that,” or, “Here are things that I never ever want to autopen.” I found it was actually common sense.

PHILLIPS: We built all of WhiteHouse.gov before Inauguration Day. We built this giant site, and we tried to figure out all the things that we would need and put it out there. Then on Day One, we started seeing that some of these sections weren’t interesting at all to people. Avoid overpreparing in terms of content. Put something simple out there and pay attention to what people care about, and then develop content toward that.

LILLIE: My first piece of advice to Trump Administration employees is to take a tour of the White House. So when the press secretary asks you to bring the press to the Map Room, or to meet at the Palm Room door, you actually know where the hell you’re going. The night that the President took the oath of office the second time during that first week, Gibbs looked at me and said, “I need you to grab the print pool. Bring them to the Map Room.” I was like, “O.K. Where’s the Map Room?” I literally just opened the door to the room, and there was the President and Chief Justice John Roberts. I thought, O.K., I guess I’m in the right place.

ABRAHAM: I just remember giving one of my first White House tours, and it was to a woman I was dating at the time and her friends. Things were so busy that I hadn’t had time to study the tour route. I was so clearly botching the facts that this very merciful uniformed Secret Service agent just stopped me and gave me a look, like, Hey, you need some help, and sort of rescued me.

PFEIFFER: There was a speech that Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner gave rolling out how we were going to deal with the banking crisis that caused our stock markets to sink as it was happening. A split screen of Tim giving his speech, and the Dow tanking, was a vivid real-world lesson. When you work on Capitol Hill, or even in a campaign, and you mess something up in messaging or rollout, it’s fine. Maybe you have a bad couple of days in the press, maybe your boss yells at you, but you don’t see billions of dollars of wealth disappearing before your eyes on live television. In hindsight, you quickly learn that it actually makes more sense to make those announcements after the market is closed.

EMANUEL: It takes a while to adjust to the fact that when you say something for the President of the United States, there’s no knob that says volume that you can turn down. It’s always at volume 10. Always. It’s the biggest microphone in the world. That takes adjusting to.

ABRAHAM: The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act passed. It was going to be the first bill that the President signed, and my boss at the time told us at our staff meeting that we were going to do a signing ceremony. Everyone was excited. After a couple seconds, my buddy and I looked at each other and our expressions slowly changed from excitement to the realization that no one yet knew how to do the little stuff. How do you clear guests into the building? How do you reserve the right room? Where do you get the pens? Who stands where?

MCCORMICK LELYVELD: The job is more defense than it is offense because you’re taking care of the family and the private life. There isn’t a protective press pool for the First Lady. What we determined was, if it’s a picture of the children at a public event, it’s fair game, or if it’s a picture that has their father in the frame. That was first tested in a photo with Sasha running down the colonnade after a Marine One landing. She was running to see her dad. It was a reminder that the White House is an office, a home and a museum. They live above the store, so to speak. The photo ran in several print organizations. I held a series of conversations with the photo editors and news editors and talked it through, reminded them of the rules. It never happened again.

BROWN: You’re in this incredible place, and you want to recognize what an honor and privilege it is to be there. At the same time, you can’t be so cowed by being there that you don’t give your best honest advice. Sometimes as a lawyer, that means effectively saying no. “I really don’t think this is a good idea.” Or, “I really don’t think you should do it that way, but here’s what you can do.” Don’t just be a yes person. That does not serve the office. History has shown this. Ultimately, it does not even serve the individual, but it certainly doesn’t serve the institution.

EMANUEL: The most important thing you can do is tell the President that you’re going to help him do his job. Like I always used to tell everybody, you can’t go in there and tell him a problem. You better offer him a minimum of two solutions. Your job is not to throw problems at him and see if he can figure out the solution.

RHODES: I love to watch Homeland and The Americans as much as anybody else, but you find yourself watching it with this kind of peculiar eye where you think to yourself, How is this person having this conversation on a cell phone? How is this person able to bring their phone into a secure working space? How did this person get into this facility? You find yourself as kind of an inspector general of the screenwriting for those shows.

ABRAHAM: If the President travels, you’ve got to have a very tight process for making sure that local elected officials know he’s going to be inbound to their state or district. I remember on one of his first trips, I didn’t realize that it was my job to notify the local member. We hadn’t really developed a standard operating procedure yet. The local member basically blasted him, blasted the White House in the press for not letting him know that we were headed to town. It was a lesson early on in my tenure. You get that world-is-ending feeling, and you’re about to throw up. Part of getting more seasoned is you realize you’re going to have a few of those. You’ve just got to minimize the number.

BROWN: People on the campaign are used to having immediate access to the candidate. That doesn’t happen anymore. You can’t have anybody wandering into the Oval Office and getting the President’s ear. It just gets very disorganized, and you can’t manage it. You need to set in place processes for whatever the set of issues is.

SUTPHEN: I used to be a big fan of to-do lists, but the to-do list actually took too much time. Because I very rarely was able to scratch things off the to-do list when I did do the to-do list, I found it a very dissatisfying exercise. I kind of stopped doing it.

BROWN: We sent senior staff clear templates for how a memo to the President should be written, how a briefing memo for an event that the President’s going to be doing the next day should be written. If you think about it, if you’re the President and you start getting stuff in a gazillion different formats, you can’t make head or tail of it.

FURMAN: There were times in 2009 when we didn’t agree on the technical design of a small-business-lending program. Because we couldn’t resolve it ourselves, we brought that disagreement to the President. In retrospect, it’s pretty embarrassing that we were bothering him with details as small as that. Big disagreement on philosophy on how to deal with autos? Bring that to a President. Should you do a 10% or 15% matching rate for your new tax credit for such-and-such? Probably worth figuring that out on your own.

BROWN: You fight this constant battle of people trying to go around you. There were days I felt like a schoolteacher, you know, rapping somebody’s knuckles. If it’s done right, people appreciate it, because they can get left out too. What goes around comes around. Your job is to be an honest broker. To tee up decisions in a fair, balanced fashion. You shouldn’t be putting a thumb on the scale. People do need to trust that.

ABRAHAM: I remember sitting in the East Wing early on when we all heard a loud noise that none of us were familiar with. Keep in mind, I had never seen Marine One land, and I’m not sure I had ever been around a helicopter. I had certainly not yet been in a work setting where it was normal for a military helicopter to land within earshot of my desk. After we realized what the heck was going on, we all ran to a window to try to catch a glimpse.

DEESE: It wasn’t until I came over here, and we had been here in government for several months, that I realized just how little we knew. I think that nothing can prepare you.

PFEIFFER: There are a lot of really good people at the White House who will help you figure out things like how to live your day-to-day. People work in the mess, and the career employees in the White House are incredibly helpful to people.

KEENAN: Fortunately, the teleprompter guys are military, so they know what they’re doing, but yes, always be nice to the prompters. You’re going to rely on people a lot more than you think. I could not do it without our fact checkers and my researchers. Be nice to everybody. They’ll save your butts from time to time.

ABRAHAM: Emotions can get high. It’s really important to remember to just be a good person, a nice person to the people around you, people you disagree with in debate, people you work with on a day-to-day basis. My personal belief is that the building functions best when there’s a real ethos of just being decent to the people who work around you.

MCCORMICK LELYVELD: There are cultural sensitivities that come naturally to the chefs because of their training. So if we’re hosting someone from another country, what are the dietary concerns? What are the celebrated foods? What are the cultural pieces reflected in cuisine that make the visit on the level that the White House should be?

PHILLIPS: I got an email in early December 2008 from two civil servants at GSA who wrote a white paper to the incoming Obama Administration. I ended up detailing one of the women who wrote it. She taught me what a detail was, which is basically that you can request that another agency lends you a person for six months. So she wrote her own detail, and I got her to come work at the White House. Then she helped me start detailing other people in, and she taught me about procurement. She taught me about acquisition, and a few months later our office had its own budget.

RHODES: For me, it’s been the foreign service. The world has changed a ton in the last 15 years, and people who’ve had to be out at embassies, understanding the constraints of other countries’ politics and other trends, often have a much better feel for what is possible and what is not than commentators in Washington. The government is full of people who have to face reality as it is every single day in every country in the world.

KEENAN: It wasn’t right at the start, but I remember the first time I flew with the President on Marine One. You still want to do your job, especially when you’re around him, so I was replying to emails. He just kind of put his hand on my arm and said, “Hey, put that down and look out the window. This is pretty special.” That’s something I’ve tried to do all along.

RHODES: You’re never as high as you feel or as low as you feel at any given time. Even when you’re at the lowest point, when everybody’s criticizing you, this is still the President of the United States and the White House. Even when you are on top of the world and everybody’s talking about how great you are, the world is still a complicated place that’s going to throw curveballs at you. You have to have that sense that every period you go through will pass.

PSAKI: On the days that you feel tired or disgruntled or frustrated, one of the best cures is to take the walk from the West Wing on the colonnade through the East Wing and out the other door of the building. It really gives you a moment of meditation. The colonnade is, of course, the walk next to the Rose Garden that the President takes home at night. I don’t think people know that the White House staff can walk that walk too. You walk into the East Wing, where there are all the grand rooms and buildings and all this history. I wish I would have known that from the first day, but I learned it pretty early on.

PFEIFFER: All of the Bush people were incredibly helpful and nice. One of the best pieces of advice that I learned was that one of the most important things you will do is keep your eye on your BlackBerry at all times. Much of decisionmaking is done by email chain, and if you miss the beginning of the chain, it could go off in a horrible direction pretty quick. You spend the rest of the day trying to unwind all the decisions that were made.

RHODES: You think you have all the time in the world. Especially when you’re at the beginning of the Administration, you’re coming in and you’re on top of the world. But you are racing against the clock from the very first day.

JARRETT: Learning the importance of time management is one of the hardest things about being here, because every minute you’re doing one thing, you’re not doing something else. And let’s face it, the minutes are finite. It becomes even more acutely clear as we get close to the end. And so I think the President would probably say he now makes decisions faster, more efficiently than he did in the beginning.

ABRAHAM: One of the great things about working at the White House is that you can call upon a really wide range of people for advice and guidance. You’ve just got to be proactive, and you’ve got to be intentional about it.

VIETOR: Bush’s National Security Council spokesman Gordon Johndroe wisely encouraged me to push for access to meetings about sensitive military or counterterrorism operations, even if there is no plan to ever discuss them publicly. His point was that because of advances in technology, it’s more likely than ever that these operations become public, and you’re far better positioned to manage the story and protect sensitive information if you’re briefed ahead of time. He was right.

FURMAN: I spent time getting to know a number of key Republican staffers. They weren’t hugely important to what we were doing in 2009 and 2010. As it turned out, Republicans chose not to cooperate. But then those relationships really paid off in helping us get things done in 2010 on taxes, in 2012 on taxes and some of the fiscal issues we were negotiating. Somebody may not matter today, but things change quickly in Washington.

VIETOR: Get to know the Situation Room staff. Bring them snacks. They’re going to be an information lifeline when things get crazy, and they’re nice, brilliant people from across the military and intelligence community. Also, they give awesome Sit Room tours if you’re nice.

KEENAN: There were a couple of other pieces of advice from the President. He’s always told us, Write what feels true. When we first came in, he asked the correspondents’ office, as I’m sure you know, to give him 10 letters a day. He told us to read these too. Keep connected to the people that sent them. Always remember why.

WiNTER: One of the beauties of the First Lady position is you make it what feels right and is authentic to you. She never felt like she had to be something other than who she was. Do what you like. Do what you love. Do what’s interesting to you, because I think folks know what is inauthentic. There must be a million photos of Michelle Obama out there, and if you look back I would tell you three-fourths of them are of her smiling with kids, because that’s genuinely what makes her happy.

JARRETT: Spend more time outside of Washington. There’s just no substitute for not just interacting with the American people, as we do here every day, but meeting them where they are. Not only is it helpful to inform our policies, but it also just is a great reminder of the grit and determination and resilience of the American people.

FURMAN: If you’re in the Trump Administration and you call a Democratic-leaning think tank to get advice about some problem, they’re going to take your call. They may go out and criticize what you do, but maybe what you’ll do will be a little bit better. The American Enterprise Institute has an annual retreat, and 97% of the people there are Republicans. I go every year. If there’s some equivalent retreat of Democrats, I would certainly advise my successors to go to it. You learn that not everything we think is right.

EMANUEL: Twice a day I would walk the halls and go put my head in somebody’s office. My rule as chief of staff was, the door is always open. I might tell you something you don’t want me to say when you walk in, but the door is always open to come in and say something. You’ve got to have that attitude. You can’t close the door. You can’t exclude.

LILLIE: There are always people all, sort of, lurking in the White House. One day I was rushing to get from the pool spray on the South Lawn for the Easter Egg Roll to a meeting in the Situation Room about a foreign trip, and there was this group of people who were just walking so slowly on the colonnade. I was just kind of impatiently waiting, and all of a sudden one of them turns around and I realize it’s Justin Bieber. And I thought, Where am I? I just need to get to the Situation Room for my trip call, and Justin Bieber and his entourage are slowing me down. So just always expect the unexpected.

RHODES: One of the interesting people I talked to over the years in this job is Caroline Kennedy. She has reflected a lot on her father’s presidency and the sense that he had really hit a stride where he felt like he knew what direction he wanted to go and knew what advice to put aside. I feel similarly with President Obama. He came to fully occupy the office and get more assertive in some spaces, taking a risk or trusting his own judgment. Being willing to take a chance and to enter into an unknown and to be willing to be criticized. That is what ultimately leads to the most rewarding outcomes.

JARRETT: There is one thing I also do every single morning, and I’ve done it for almost eight years now, starting on January 20th of 2009. I met a guy on the campaign trail in Austin, Texas, back in the primary season, early in 2008. He was operating the elevator for us, and he asked the President if he could give him something, a patch from his military uniform. The gentleman said to the President, “I’ve carried this patch with me every day for 40 years, and it has kept me strong and been with me through some tough times.” And I thought it was such an incredible act of unselfish generosity that I made up my mind that I would think of him every morning when I drive through the gates of the White House, just for a few seconds, and that that would remind me why we’re here. It helps me deal with the toxicity of Washington.

RHODES: You can find a reason to stay at work all night, every night here. There is always going to be something to do. You are never going to clear out your inbox. You are never going to return every phone call. You are never going to read every paper that you could. Ultimately, if you do that, you’ll be worse at your job. Not only will your family life suffer, but you will lose some perspective.

DEESE: You have to make a very conscious effort to reach out, to talk and interact with and communicate with people outside of the bubble that you are entering. The intensity is so high that you can easily go for weeks or months without real meaningful contact outside. That puts you in a position where you won’t do your job as well. It can also put you in a position where you are sacrificing relationships and people that matter in a way that you’re burning the candle down to the end.

PFEIFFER: It is a suboptimal process where you work your ass off for two years on a campaign, are totally exhausted, and the prize you get is a much harder job that also keeps you away from your family and friends that could last anywhere from four to eight years, depending on how long you want to do it. If I look back, I remember weddings of very close friends I had missed, not seeing my family, like my parents and my brother, for almost the entire first year. I didn’t take a vacation of more than a day or so from the day we walked in the White House until April 2010.

KEENAN: Your lives are no longer your own. I mean, if you plan a date with somebody, if you have a weekend planned, a wedding, none of that is yours anymore. Work-life balance doesn’t exist.

RHODES: Some colleagues very much focused on going home at 5 p.m. one night during the week. For me, I didn’t work on Sundays unless I absolutely had to. I tried to go home and eat dinner every night that I could.

PSAKI: After I had a baby, I wanted the day care to always be able to reach me. I gave them my assistant’s phone number, because I’m often in meetings where I can’t bring my phone. There are things like that that are not that complicated but you have to do in order to be accessible to your loved ones.

RHODES: Negotiating day-care drop-offs and pickups takes some precedence. I did have a number my wife could call if I needed to get to day care, or there was an emergency. There is kind of a red phone. You know there’s a possibility that you were going to miss a meeting that you never would have missed otherwise. After you have a kid, that happens.

EMANUEL: I used to joke, “The White House was family-friendly—to the First Family.” The other thing I used to joke in the White House was, “Thank God it’s Friday. Two more workdays till Monday.” I used to carve out Friday nights for Sabbath. I wasn’t really great, because I still stayed on the phone, and then Saturday or Sunday we’d always take a half-day as a family to do trips around. We went to Gettysburg, other battlefields. I can be connected by phone, try to do something with my family, but it’s brutal. There’s no way you don’t take that job home with you.

FURMAN: They now have a children’s-access list. If you have a child under the age of, I think, 14, you don’t need to waive them in in advance. Back then, they didn’t have that. I remember one weekend, I got something on a Saturday that required using my computer. I was at one of the museums with my 2-year-old. I come to the White House with my 2-year-old and I say, “I need to come in to use my computer,” and they won’t let him in.

PFEIFFER: After we passed the Affordable Care Act, we were sitting in Rahm Emanuel’s office. I’ve done nothing else but work on health care for, like, nine months. Everyone is now worried about the communication about implementation, and how we’re going to handle that, and what am I going to do. I, like, snapped at David Axelrod in a pretty aggressive way, which I would not normally do. He’s not someone who engenders that sort of behavior, and he just looked at me, like, “Brother, man, you seem pretty frayed at the edges.” I was like, “I’ve got to go on vacation.”

SCHULMAN: Nitro coffee at the mess is a true revelation. It’s a revelation that will serve the next Administration well.

DEESE: As somebody who is a regular consumer of coffee, there is a window between 2 and 3 p.m. that the mess is closed. Most days, you don’t lift your head up to think about having lunch or a cup of coffee till 2:05. I feel like I end up most days in the dead zone between 2 and 3 p.m. You want to plan your day to not get caught in the dead zone.

KEENAN: Wednesday is Taco Wednesday at Ike’s in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, and Thursday is taco day in the mess. I’ll probably get in trouble for this: chips and queso are not on the mess menu, but if you ask for it, they will make it for you.

RHODES: In addition to not having your phone for long stretches of time, there are some times that you’re very busy, but you can’t tell anybody why. I remember in the month leading up to the bin Laden raid, there were lengthy workdays on the weekends or nights when you couldn’t really say what you were working on or why you weren’t going to be at home. That is a strange feeling. You know why you’re unavailable, but you can’t really explain to people why you can’t make it to this dinner or you can’t be available. That happens a fair amount in national security. Your wife gets used to it, and the people in your life get used to it.

SUTPHEN: My advice, which I didn’t follow the first time I was in the White House, is to join the gym. Because the combination of sitting basically all day, the stress, three meals a day at the White House mess is just a recipe for being super-unhealthy.

JARRETT: I have brunch every Sunday with the same group of friends. Relatives or friends who I’ve known in some cases my whole life, all of them at least 25 years, long before any of this happened. The ritual of seeing the same people every Sunday for brunch, and then I have dinner most Sundays with my family who lives here—I find that helps. We don’t talk about work, we talk about what normal people talk about, and that allows me to catch my breath. Whenever we are all in town, that brunch and dinner are sacrosanct.

LILLIE: I did every international trip twice during the first 2½ years of the Administration. It’s a lot of miles. People often ask me where my favorite place was that I traveled. It’s so difficult for me, because my experiences are not real-life experiences. My experience is you go to Moscow and you’re inside the Kremlin. I’ve been inside 10 Downing and Buckingham Palace.

PSAKI: The President travels with three planes, so it is very difficult to coordinate and for people to stay in close touch and really for everybody to have all of the information they need.

LILLIE: What I always tell my advance staffers is that a lot of times you are the closest someone will ever get to the President. Your behavior and what you do could wind up on the front page of the New York Times. It reflects on him and on this Administration, at every point. Whether you’re at a bar in Washington, D.C., or overseas. You also still need to have fun and live your life, but I think it’s important to remember that you can’t ever turn that off.

VIETOR: It’s not just that people might recognize you. It’s that D.C. is filled with people who will actively try to hurt you, so be mindful of talking about work in public. You will inevitably be overheard.

WINTER: The reception that the First Family received virtually anywhere they went in the world was always so overwhelmingly positive. Some places they literally would just line the streets, in a way that you’re thinking, Don’t these people have to go back to work? There was this feeling at some points that the First Lady was like a global superstar. But you know what? A lot of these trips, we had Malia and Sasha and Grandma with us. We’d go back to the hotel and we’d be asking, “What do the kids want for dinner?”

PFEIFFER: The one thing I’ve learned in my post–White House life is that your body and mind and emotions will adjust to that lifestyle. You have a new normal. The level of stress and exhaustion that I lived with for six years in the White House. I’ll look back on it and think it’s insane.

LILLIE: You need something to help you sleep. Ambien is not the way to go. It lasts eight hours. You will not get eight hours. Sonata—I feel like I am doing an ad for a drug company—Sonata was my lifesaver, because it only really lasts four hours and it’s out of your system, so it’s perfect for plane rides, for nights when you’re not getting more than four hours of sleep.

RHODES: On the 2009 trip to Moscow, I was a speechwriter at that time. Back then, when the President would leave and go to all of his meetings, I would stay at the hotel and work in the staff’s workspace. It was the middle of the day. I was working in the staff office, and I went back to my room to get something, and the cleaning lady was there and there were three guys in suits going through all my stuff or doing things in the room. As soon as I walked in, they put everything down and walked out of the room without saying anything.

LILLIE: In one country, I got to my hotel room, I was just so tired, just ready to pass out. I throw my BlackBerry down on the bedside table and it starts making the noise that it makes when you put it next to an open mike. I was like, “All right, I guess there’s that!” You never know what you’re going to find. You just get used to it.

VIETOR: There’ll be times you feel completely overwhelmed, miserable and under siege. The hours can be brutal and the stakes are high. But as frustrated as you might feel in the moment, know that you’re going to miss the job when you’re gone. You get to be a part of something that’s bigger than yourself. The people you work with will be lifelong friends. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Savor it.

JARRETT: I think one of the pieces of advice that I received was that the days last forever, but the weeks, months and years fly by. And that is very, very true. Every single day I think, Goodness, that day lasted forever. And I cannot believe I’ve been here almost two weeks shy of eight years.

EMANUEL: If you ever drive into the gates of the White House and you still don’t have a tingle in your spine of how special this is, it’s time to leave. Even in the darkest moments and the toughest slog-throughs, it’s special. I mean, it’s going to be tough, there’s no doubt and advice on that, but if you don’t still have a tingle that this is special, then it’s time to go.

LILLIE: I used to walk up to the White House gate sometimes and expect them not to let me in. Because it’s just that amazing working there. The thing is that one day they won’t let you in. That happens to everyone.