It was once the richest country in Latin America. Now it’s falling apart

By Ioan Grillo / Caracas | Photographs by Alvaro Ybarra Zavala

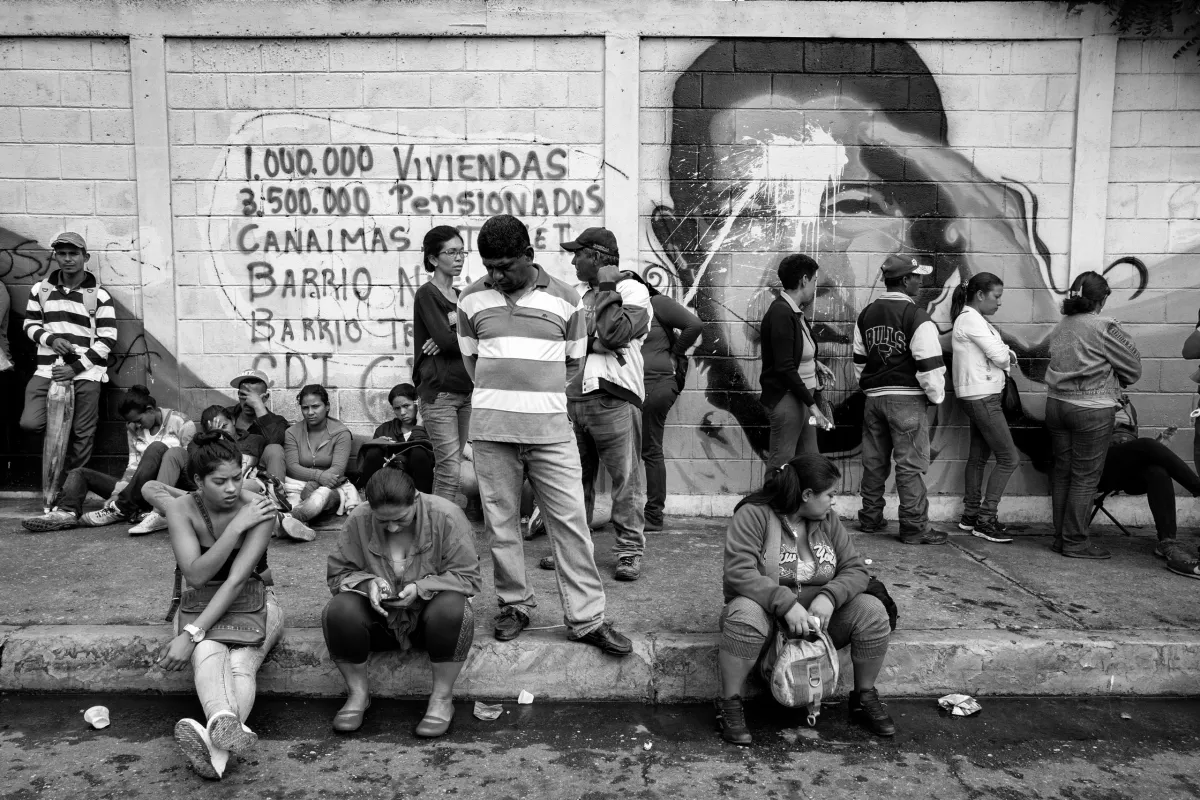

In Venezuela the food lines are only the most visible evidence of a nation in free fall. Known as las colas, the lines form before dawn and last until nightfall, several bodies thick and zigzagging for miles in leafy middle-class neighborhoods and ragged slums alike. In a country that sits atop the world’s largest known petroleum reserves, hungry citizens wait on their assigned day for whatever the stores might stock: with luck, corn flour to make arepas, and on a really good day, shampoo.

“I never dreamed it would come to this,” says Yajaira Gutierrez, a 41-year-old accountant, waiting her turn in downtown Caracas. “That in Venezuela, with all our petroleum, we would be struggling to get corn cakes.”

In the capital’s Dr. José María Vargas hospital, a doctor watched a 73-year-old woman die of kidney failure because the hospital lacked the medicine to perform a routine dialysis. In a Caracas police station, more than 150 prisoners crowded into a cell made for 36, standing shirtless (there was no room to sit) in the stench of sweat and feces. In arid Lara state, an elementary-school teacher told of children fainting in class from hunger. The economy contracted by almost 6% last year, and is expected to shrink by as much as 10% this year.

Venezuela was once Latin America’s exemplar: home to Simón Bolívar, who freed much of the continent from Spanish rule. Now, after years of political mismanagement and months in economic free fall, it is the region’s cautionary tale. The bolivar, the currency named for the Liberator himself, is now carried in backpacks instead of wallets; one unit is worth less than a penny. While production plummets, crime soars. Fights frequently break out in food lines. The number of murders last year ranged between 17,000 and 28,000. No one knows the exact tally, but regardless it would put the nation’s murder rate—driven by a lethal mix of street gangs, drug cartels, leftist guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries jostling for power—among the world’s highest. Even animals are dying: some 50 zoo animals have starved to death over the past six months because there’s not enough food.

“It is like there had been a natural disaster, like a hurricane which swept things away,” Henrique Capriles, the governor of Miranda state and a key opposition leader, tells TIME. “If we don’t look for a democratic constitutional solution, I fear there will be an explosion in Venezuela, and it will finish collapsing.”

Reaching that solution seems all but impossible in a country still ruled by the legacy of a dead man. During the 14 years Hugo Chavez spent as President before his death in 2013 from cancer, he set in motion the economic and political dynamics that created the current catastrophe—and the paralysis that has resulted from it. In Venezuela, almost every politician—and many ordinary people—still define themselves as being either a Chavista or as opposition. The current President, former bus driver Nicolás Maduro, claims the Chavista name but has none of his mentor’s charisma—or for that matter his good fortune. Chavez enjoyed sky-high oil prices for much of his time in office, but on Maduro’s watch oil prices have dropped from $100 a barrel to as low as $25 a barrel. (It’s now at $35 a barrel.) Chavez enjoyed massive popular support, but in the December 2015 midterm elections, the opposition won a majority of the assembly for the first time since 1998.

But the opposition has been able to do little with its new power—thanks again to the legacy of Chavez. Chavista judges in the supreme court have struck down 18 laws or motions passed by the assembly, among them one decision that overturned a law ordering the release of more than 100 political prisoners, including opposition leader Leopoldo López, jailed in a case the prosecutor himself said was rigged. Blocked in the legislature, the opposition is instead taking direct aim at Maduro, gathering more than a million signatures to demand a recall referendum that would remove him from office. Surveys indicate that the President would lose badly, but Maduro still has the tools of the state at his disposal. Those include the military and the police, which on July 27 blocked opposition protesters attempting to march on the National Electoral Council’s headquarters in Caracas.

Maduro has made it clear he’s going nowhere. In May he declared a state of emergency, ordering military maneuvers to prepare for an imagined foreign invasion. On TV, he blames the crisis on rich Venezuelans working with the CIA and Colombian paramilitaries across the border. A group of Chavista militants march daily in defiant support of their embattled President. “We are ready to spill our blood defending the patria [homeland],” says Endri Carvajal at a rally of Chavista motorcycle taxis. “If there is an intervention, their soldiers will die here.”

Venezuela shouldn’t be like this. The country sits on 18% of the world’s proven oil reserves, adding up to nearly 300 billion barrels. But what the Venezuelan diplomat and OPEC founder Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo once called “the devil’s excrement” has been a mixed blessing from the start, enriching a moneyed elite even as the poor cling to life in hillside shanty towns like the Petare slum above Caracas, home to half a million people.

Despite gaping inequality, however, Venezuela remained relatively peaceful until the late 1980s, when oil prices hit a prolonged slump. Protests over economic conditions deteriorated into looting, and amid the turmoil, a young paratrooper named Hugo Chavez attempted to lead a coup in 1992. Chavez would serve two years in prison for his actions, but he eventually rebounded to win the presidency at the ballot box in 1998. He began as a straightforward populist who made little mention of socialism, focusing his wrath on Venezuela’s corrupt establishment while winning the hearts of the poor with his charisma.

But after surviving a failed coup in 2002, Chavez took a radical turn. He started launching daily broadsides against rich Venezuelans and their American friends. The U.S. was already a convenient bogeyman in Latin American politics, thanks to a long history of sponsoring coups, outright invasions and puppet governments. Chavez took special aim at then U.S. President George W. Bush, whom he cast as a literal devil, quipping that the lectern “smells of sulfur still today” after following Bush in a 2006 speech to the U.N. General Assembly.

By then Chavez was a rock star for the global left, which thought it had found a post-Cold War model in what the Venezuelan President called his Bolivarian revolution. But Chavez always practiced a strange kind of socialism, relying on Venezuela’s oil industry as much as any capitalist predecessor. With oil eventually rising as high as $140 a barrel in 2008, his government was building a million new homes and corner medical clinics (many staffed by Cuban doctors, part of a crude-for-medicine deal with Havana) and even handing out laptops and washing machines in the barrios. “We said that Venezuela became the country of the happy poor,” says economist Eduardo Fortuny. “Without really improving their income, he gave them more things. Chavez’s popularity went hand in hand with his public spending.”

Chavez also fixed prices on basic foodstuffs, from coffee to cookies. When it became unprofitable for Venezuelan companies to make such things, Chavez simply used oil money to import them from abroad. Winning election after election, he went on to expropriate hundreds of private companies, from sugar plantations to dairy farms. And to stop people from dumping their bolivars, which were losing value, he restricted who could buy dollars and fixed the rate.

Those measures sowed the seeds of the current crisis. Unable to legally buy dollars, businessmen turned to the black market, where exchange rates soared. While the official base rate is 10 bolivars to the dollar, the bolivar now trades on the street at more than 1,000. The collapse of the currency is aggravated by oil’s low price—Venezuela can no longer count on its oil exports’ bringing back enough dollars, which means it can’t import enough goods to sell at the fixed prices, leading to shortages.

And domestic production has been decimated as farms and factories that Chavez expropriated are all but idle. The crisis has hurt international companies as well, which have seen some $10 billion in profits wiped away over the past 18 months. Many are giving up on the country. In May Coca-Cola suspended its bottling operation in Venezuela because of a lack of sweetener, and in July McDonald’s temporarily stopped selling Big Macs because of a lack of bread.

As bad as things are in Caracas, the misery is worse in the provinces. Mario Mora, a 52-year-old laborer, sits in the searing sun in the town of Pavia after waiting since dawn for an arrival of gas canisters to cook and heat water. The wait is in vain—at 4 p.m., a police officer informs the crowd that no gas will arrive until the next day. Mora will have to forage for twigs to make a fire in order to cook corn cakes and beans for his wife and four children. They eat one meal a day. “I have always been poor, but I have never seen it as bad as this,” he says.

Hardly better are those in the urban middle class who call themselves “the new poor.” Yajaira Gutierrez, the accountant waiting in a food line in Caracas, says that five years ago, her salary was worth about $800 per month. Now, despite regular raises, it would equal less than $70. When she can’t get food in the shops, she turns to the black market, where hawkers sell foodstuffs for 10 times as much as the stores. “I have been cleaning myself with the soap meant to wash dishes,” she says.

Medicines often can’t be found at any price. After businessman Rainer Espejo discovered that his 2-year-old daughter Barbara had leukemia, he had to turn to a neighbor who worked in Colombia to smuggle the drugs she needs. With the power cuts, Barbara is going through treatment with sporadic air–conditioning and water shortages that make it hard to keep her clean. “It is a cruel form of survival,” says Espejo. “You can get depressed. But the problem is still there, so you have to face it.”

No less striking are the packed jails. Some prisoners get access to water just one hour per day, urinating and excreting in plastic bags that they wait for the guards to collect. “In these conditions, your mind deteriorates,” says Daniel Sayago, 24, who has been accused of mugging. “You have to shut down parts of it to survive.”

For opposition leader Capriles, the only meaningful change means recalling Maduro, whose term runs to 2019, and holding new elections. Capriles says that a new President—which could mean him—would be able to eliminate the price and currency controls while alleviating the side effects with humanitarian aid from abroad that’s more likely to flow to a friendlier government.

But the fate of the country may ultimately rest on the army, another player in a political realm crowded with armed groups. The military has so far backed Maduro, but it has successfully overthrown Venezuelan governments three times in the past 70 years, and Chavez filled the top ranks with allies following the 2002 coup attempt. “The armed forces are arriving at a difficult hour, decisive,” says Capriles. “And they are going to have to take a decision: Are they with Maduro, or are they with the constitution?” — With reporting by Jorge Benezra/Caracas