Text & Audio by Jeffrey Kluger—Author of Apollo 13 & Apollo 8 All Photos Apollo VII—XVII/NASA

Nobody ever accused the Apollo program of failing to deliver the goods. There were the 842 pounds of moon rocks and the raft of scientific spinoffs and the deep thrills that every one of the 11 missions delivered. And then, perhaps more than anything, there were the pictures.

We are equal parts a questing species and a very visual one. We go places so that we can see what is there and we carry our cameras so we can bring home evidence of those sights. That’s especially important when the destination is one that only 24 human beings out of all of the billions who have ever lived have gotten to visit.

For that reason, NASA made photography a high priority during the Apollo missions, redesigning cameras that could operate in the punishing environment of space and inventing ultra-thin film that would allow a single roll to contain 200 exposures. Of the thousands of pictures taken, only a comparative few were chosen for the public to see. They were the best of the images, no surprise, and that made sense. But their very perfection sometimes made them seem almost sterile. It was the outtakes—the astronaut in the clumsy pose, the litter left on the lunar surface, the too-bright sun flaring off the lens—that revealed the missions to be the often unglamorous, often improvisational camping trips they were.

Now, a team of four European designers have chosen 225 of the least seen—and in some cases least polished—of the Apollo trove and released them in a dazzling book titled “Apollo VII – XVII.” The wonderfully imperfect collection provides an entirely new perspective on the flights we thought we knew.

listen

Apollo VII was the first test drive of the Apollo spacecraft, limited to Earth orbit, yet it offered glimpses of the more ambitious flights to come. The crews would get nowhere near the moon without the upper stage of the giant Saturn V rocket, which would blast them out of Earth orbit and would carry the lunar module like a kangaroo joey in an onboard compartment. On the way to the moon, the petals of that compartment would open and the lander would be extracted. Apollo VII practiced that maneuver in Earth orbit, with no LEM aboard. The close-to-home pantomime would play out for real just a few missions later.

From the high ground of space, it’s almost impossible to take a bad picture of the jewel box landscape below, but the Apollo VII crew managed that ignoble feat. The odd framing and poor sun control in this shot destined it for the discard pile. But that’s Florida below, with the north end of the state to the left and the south to the right and the embarkation point—Cape Canaveral—visible as a sharp projection along Atlantic coast. The red light on the Gulf of Mexico and the comparatively low angle of the sun create the mood of a tropical sundown—a little bit of beachfront bliss that was, at that moment, entirely out of the astronauts’ reach.

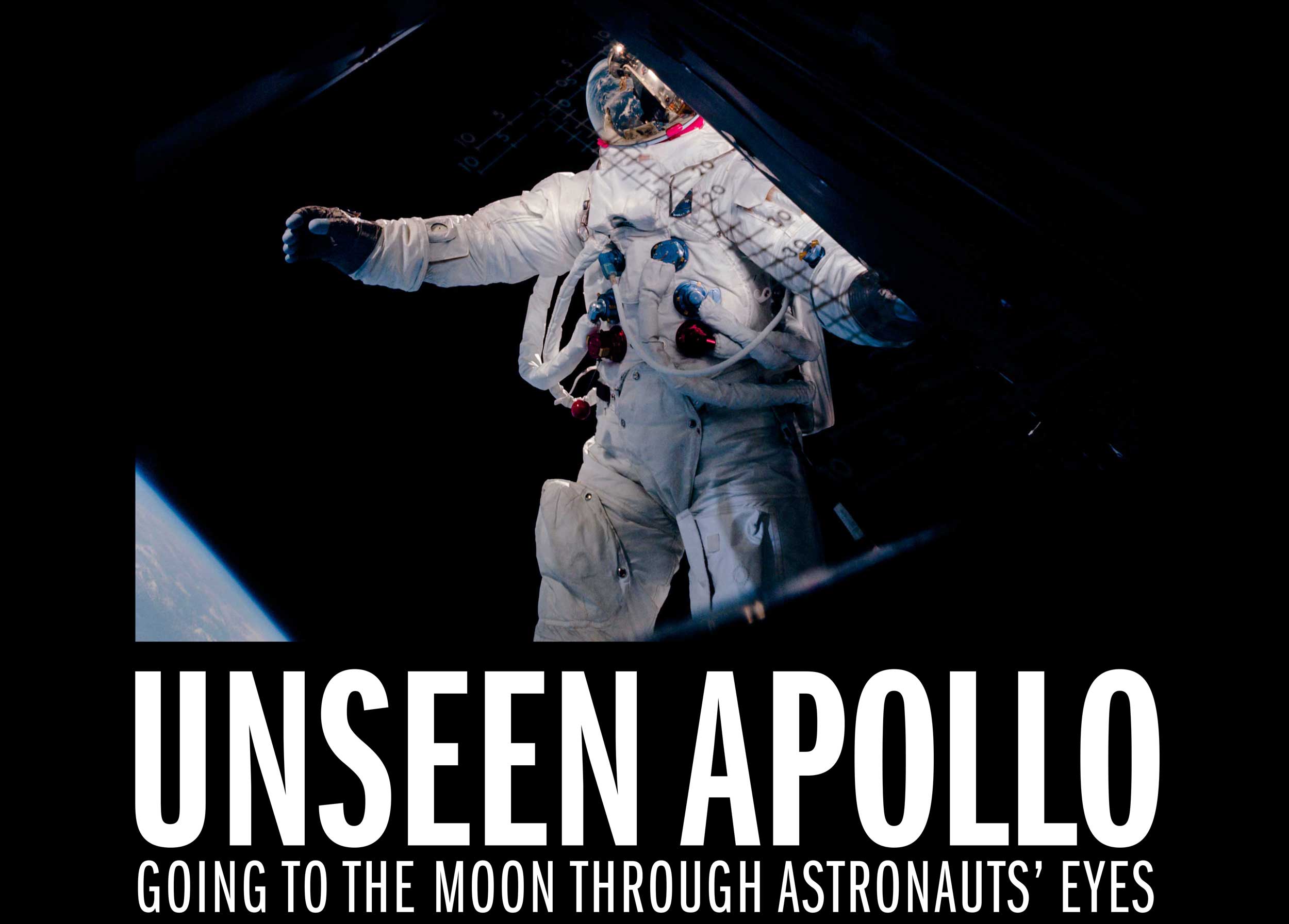

The Apollo IX mission test-flew the command module and lunar module together in Earth orbit. Dave Scott’s spacewalk was one of the most-photographed parts of the mission and one of the images—brilliantly lit, artfully composed, showing both spacecraft in a single frame—became a NASA icon. But the truth was closer to the outtake here, with Scott emerging as the spacecraft flow over the nighttime side of the Earth, a solitary man almost lost in shadow, venturing from the safety of the Apollo burrow into the killing cold of space.

Spaceflights were often reconnaissance missions and dirty portholes could make that job impossible. Gas trapped between layers of glass or moisture picked up on the way out of the atmosphere could make windows impossible to use, though the fogging or streaking would often clear up as the sun warmed the spacecraft skin. The public saw only the pretty pictures shot through clear windows, but here the Apollo 12 crew took a shot to show NASA the challenges they faced.

The cockpit of the LEM was supposed to be a bright and active place, but on Apollo XIII it became a darkened still lifeboat, as the crew shut down nearly all of its power and took refuge in the hope of getting home after an explosion disabled their command module. In the middle of the instrument panel a label that reads “lunar contact” is barely visible. A blue light beneath it was supposed to flash on the moment the lunar module made contact with the lunar surface. On Apollo XIII, it remained forever dark.

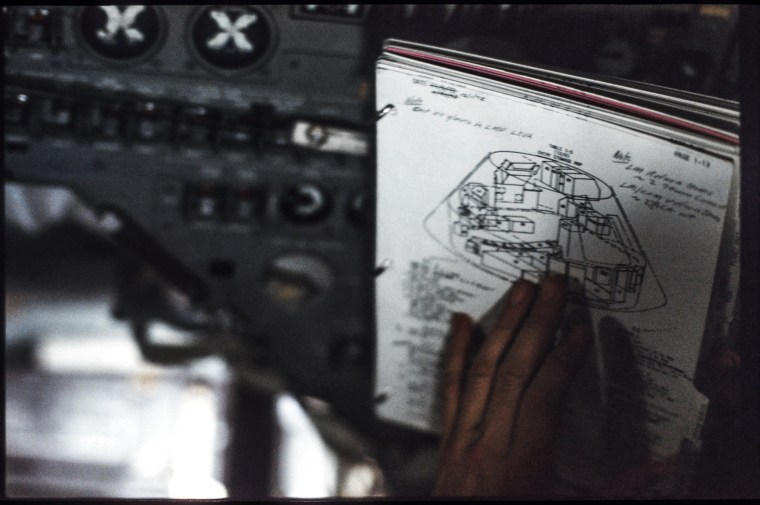

The Apollo program was a pencil-and-paper enterprise. The missions were conceived and flown in the era before calculators and touch screens and heads-up displays. Flight plans, which would today be loaded on a tablet, were similarly low-tech—printed on heavy fireproof paper bound in loose-leaf form. There’s nothing spacey or sexy about this shot from Apollo XVII, with one of the astronauts checking the schematics of the command module, which is why NASA saw no need to release it.

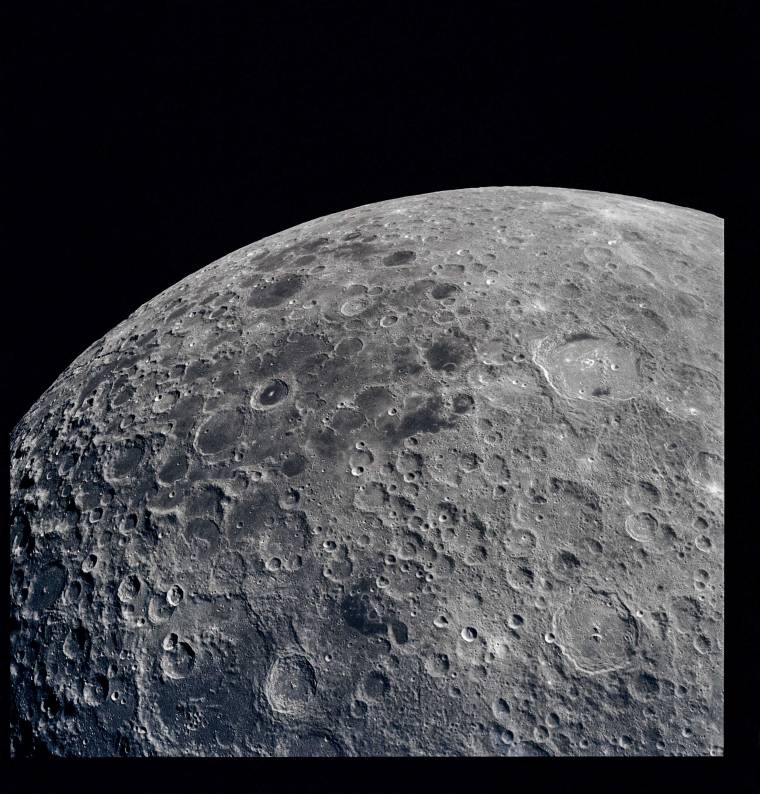

During all of the lunar flights except the last, crews surveyed the ground below to study future landing sites. Heavily cratered regions like these, photographed by the Apollo XVII crew, dominate the far side of the moon and frame the so-called seas on the near side. They were no-go zones for landings since the ground was so uneven. It was the seas—which are actually great plains that resulted from ancient lava bleeds—that were the first targets.

The ancient, desiccated moon that we see from a distance belies a certain fluidity that’s visible up close, as captured by the Apollo 15 crew. Like the volcano fields on the Hawaiian island Hilo, some regions of the moon have preserved the state of the landscape just as it was when the lava that flowed across it hardened. Snaking channels like the one that twists about a third of the way up the image from the bottom of the frame might have been lava riverbeds. Apollo missions never flew during a full moon, since the far side would have been blacked and on the near side, the overhead sun would have eliminated shadows, which, as in this image, can help highlight topography.

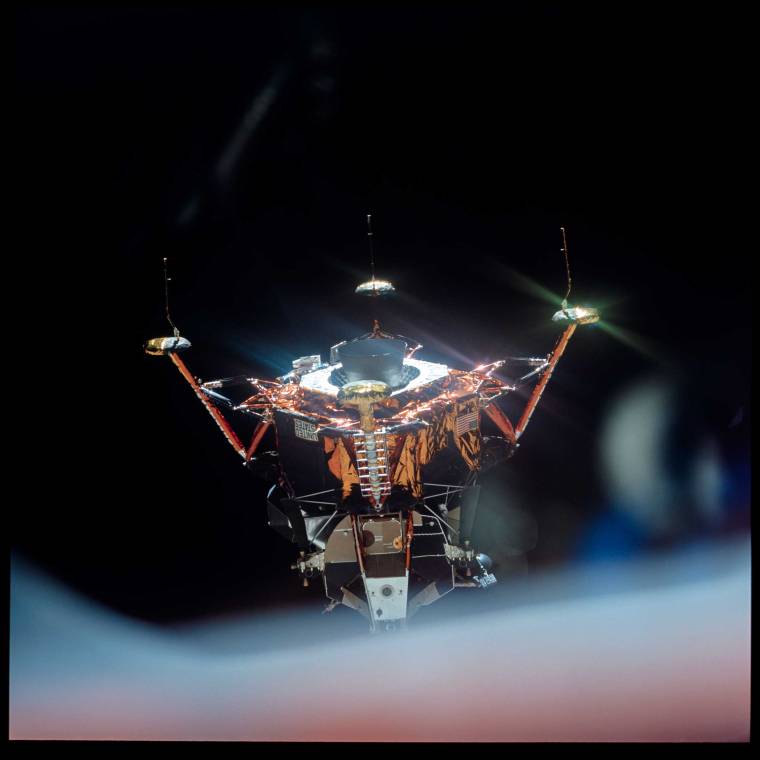

The lunar module was a whimsically ugly machine. That’s what happens when you can design a vehicle strictly for functionality with no concern for the aerodynamic sleekness that is necessary when you’re flying through the atmosphere. Here, the Apollo XI LEM has separated from the command module and hangs, seemingly upside down (though there is no upside down in space) before the camera of Michael Collins, left alone in the command module. The rods extending from the foot pads are contact probes. When one of them touched the lunar surface, the contact light would flash on in the cockpit, telling the commander to cut the engine.

From some angles, the irregularly shaped LEM could achieve a certain doily-like symmetry. Apollo XIV’s Stu Roosa captured this image of the top of the lander as it drifted away from the command module. The dark circle at the center of the roof is the docking port, where the nose of the command module would connect, allowing a tunnel to be opened between the two ships. On the LEM leg at the 2 o’clock position, the ladder that astronauts Al Shepard and Ed Mitchell would later climb down to the lunar surface is visible.

Apollo XV almost came to ruin the second it touched down. NASA had strict rules about how sharp an angle was safe for a LEM landing, and a 15-degree slope was the absolute maximum. Any steeper and liftoff could be compromised. The moon’s Hadley-Apennine region was treacherous, however, and the 10-degree incline of the landing spot was the best the crew was able to find. NASA was happy to release images of the Apollo XV LEM photographed from the front, but profile shots were kept under wraps.

On the last three landing missions, the country that led the world in the manufacture of cars also sent them to the moon. The lunar rovers never traveled faster than about 11 mph (18 km/h) though in the moon’s 1/6th gravity, that provided what felt like a light, speedy ride. Here, Apollo XVI’s John Young leans seemingly jauntily against his ride, with the overexposed top half of the image creating the overall effect of a casual vacation shot snapped during an off-road trip in the desert southwest—minus the can of beer that really ought to be perched on the fender.

The business of planting the American flag on the lunar surface never got old. The larger view was always the better one, of course: American astronauts were emissaries not of a nation, but of a species. But the 205 million members of that species who lived in the United States still thrilled to the image of the stars and stripes. On Apollo XII, it was Al Bean’s job to plant and position the flag—which was stiffened in the airlessness of the moon by a rod stitched into its top edge. Commander Pete Conrad, like generations of vacation photographers, is visible only as a long shadow.

The 12 men who walked on the moon had to reckon with a problem no photographers in history ever had before: how to manage sunlight that streams straight to the camera with no intervening atmosphere to soften and color it. Not every attempt was a success, as this shot by Apollo XII’s Pete Conrad shows. But there’s more to the image than the giant sunburst. There’s also a sense of the hard work that the lunar missions required, as Al Bean lugs scientific equipment into the field for placement on the surface.

There aren’t a lot of straight lines on the tumbledown surface of the moon—or at least there weren’t until humans arrived. Apollo 17—like Apollos XV and XVI—left tire tracks nearly everywhere they traveled. In the windless, rainless, erosion-free environment, the tracks endure, close to half-a-century on. This image, captured in a haunting black and white that was not at all in keeping with the kinds of images NASA liked to release, captures what a lonely business making those permanent marks could be.

It was often hard to tell the difference between the litter and the scientific experiments the Apollo astronauts left on the surface, as this image from Apollo XIV shows. In this case, the shot is of science; the gold, boxy object is the central station of what was known as the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP). The tarp-like circle of silver with the can-shaped object to the left is the seismograph, one of six instruments that made up the ALSEP. The last of the experiment packages left on the surface winked out on Sept. 30, 1977, close to five years after the final lunar landing.

The last three Apollo missions visited hilly and even mountainous terrain that the first three didn’t dare try. The Apollo XVI crew visited the Descartes Highlands, where mountainous uplift exposed geology that was not available on the flatter plains. Long shadows and black-and-white film convey a sense of how far-ranging the field expeditions became.

After the first of three lunar expeditions, the fender on the right rear wheel of the Apollo XVII lunar rover broke off. “Oh, there goes a fender. Oh shoot!” commander Gene Cernan could be heard exclaiming on the air-to-ground loop. That was a problem because lunar dust is finer than confectioner’s sugar and in the 1/6th gravity of the moon, it got kicked up easily by the rover’s tires, potentially fouling machinery and even the astronauts’ life support equipment. The solution: four lunar maps folded just so and fastened with what Cernan called “good old-fashioned American gray tape.”

If there was one sight that could make an Apollo astronaut nervous, it was this. The Earth in this image from Apollo XI looks dauntingly far away and the lunar module—which appears to have been stapled together from sheet metal—seems barely up to the task of making the trip off the surface. In fact it was more than capable, and its lightweight design was one of the thing that made it so flight-worthy. Only the top half of the lander—the silver section, here photographed from behind—would lift off from the moon. The bottom portion—the mostly gold colored struts and legs—would serve as a launch platform and remain behind.

The gray-white moon had nothing on the riot of color that is the Earth, and the astronauts felt the pull of the home planet throughout their trip. The closer they came on their return journey, the more the Earth loomed. In a striking image taken by Apollo 17, almost the entirety of Africa is visible, with the southern portion of the continent at the bottom of the frame and the vast expanse of the Sahara Desert at the top.

Taking good pictures is never easy. It’s harder when you’re mummified in a spacesuit that includes gloves that eliminate nearly all dexterity. And it’s harder still when you’re doing some of that photographic work while jouncing along in a lunar rover. For that reason, Apollo crews spent a lot of time practicing, as Apollo XVI’s John Young (right) and Charlie Duke did not long before their April 16, 1972 liftoff.

The full book Apollo VII – XVII by Simon Phillipson, Joel Meter, Delano Steenmeijer, & Floris Heyne is available now. Purchase it here.

Jeff Kluger’s latest book Apollo 8 will be released on May 16. It is available for pre-order here.

Correction: The original version of a photo caption accompanying this story misstated how long Apollo 17 tire tracks have endured on the surface of the moon. It is almost half-a-century, not almost half-a-decade. The original version of another photo caption misstated a label on an Apollo 13 instrument panel. It said “lunar contact,” not “contact light.”