Short List

Person of the Year

The Short List

THE SHORT LIST: NO. 4

PERSON OF THE YEAR 2017

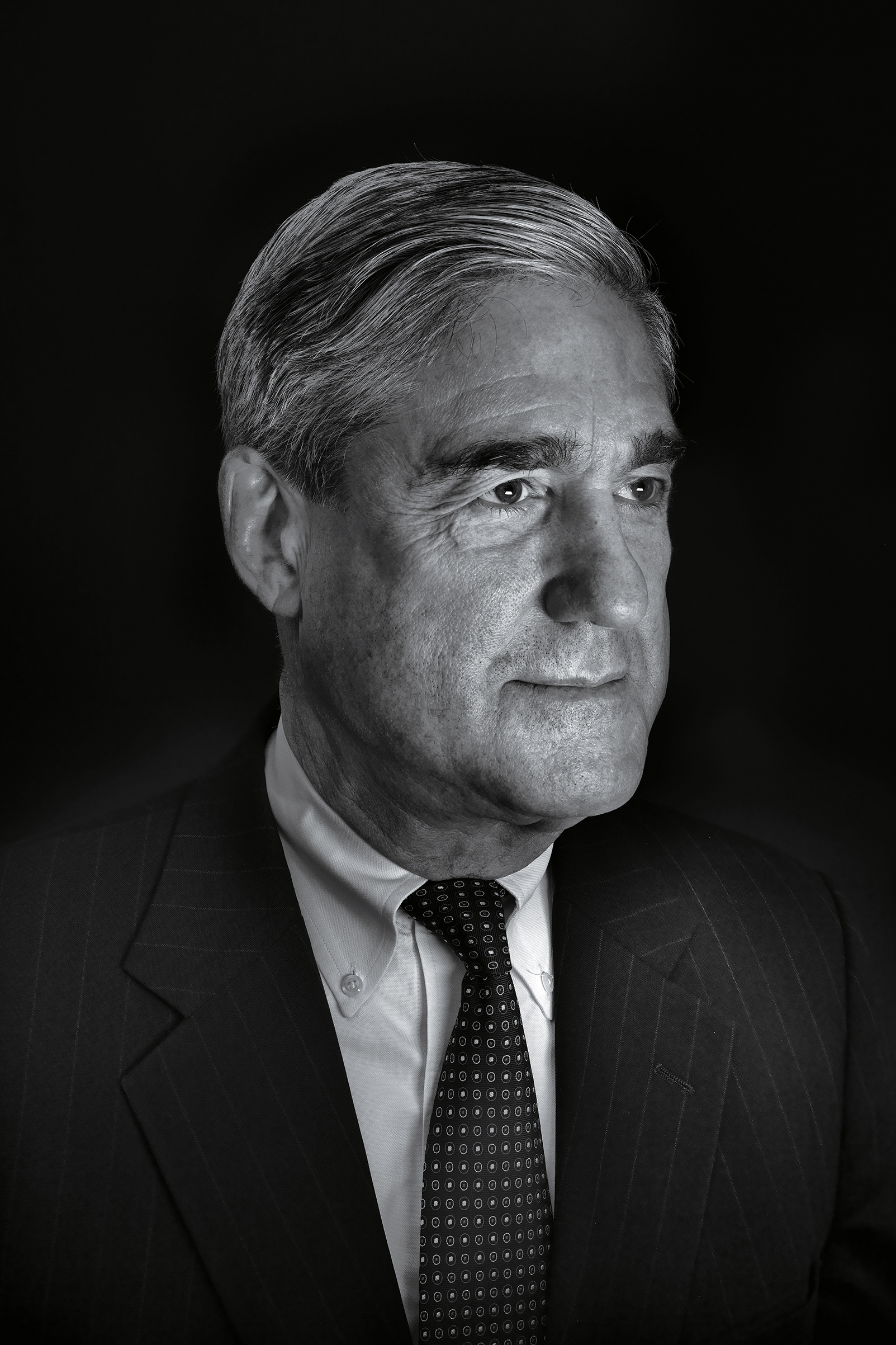

Robert Mueller

A prosecutor known for rigor and rectitude goes after the president’s men

Massimo Calabresi

On May 17, the U.S. Department of Justice gave Robert Mueller a mission at once simple and daunting: investigate the Russian government's efforts to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election; uncover any coordination between Moscow and members of Donald Trump’s campaign; and prosecute any crimes that were committed in the process.

Since Mueller took up that task, the special counsel has held the country in his thrall. Backed by an independent budget, rare bipartisan support and a team of veteran cops and prosecutors, he has made news even when he tried not to. Loose-lipped lawyers for Trump and his associates leaked details of the probe to the media. Scraps of evidence made their way into public view from separate investigations in Congress. And the President, not known to be a target of the probe himself, fumed publicly as his first year in office was consumed by the once-in-a-generation spectacle of a powerful prosecutor on the trail of the President's men.

Watch: Why the Silence Breakers Are the 2017 Person of the Year

The tension rose when the special counsel started laying out his case. On Oct. 30, Mueller charged Trump's former campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, and Manafort's deputy with money laundering and other crimes, and secured a plea deal and pledge of cooperation from a low-level campaign adviser. A month later, on Dec. 1, Trump's former National Security Adviser, retired Lieut. General Michael Flynn, pleaded guilty to a single charge of lying to the FBI and swore to tell Mueller everything he knew about contacts that he and others had with Moscow.

As the investigation edged closer to Trump himself, and speculation ramped up about where it would all lead, it was easy to forget the essential dynamic of how it all began.

Washington is all about rules. One branch of government writes them, another settles arguments about them, the third enforces them. The high political drama of 2017 flowed from the arrival in our nation's capital of a roguish figure elected on the exhilarating notion that rules are to be flouted. But what felt liberating on the campaign trail proved challenging in a city built on constraint, where every 12th resident is a lawyer, or an officer of the court.

There is barely a handful of people in all of America with the reputation and experience to take on the task of untangling a multipronged Russian influence operation from one of the most disorganized presidential campaigns in memory. After Trump fired FBI Director James Comey in May, initiating a crisis at the very top of government, the sighs of relief in Washington were audible when Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein named Robert Swan Mueller III to the task of investigating. Democrats and Republicans alike praised the patrician former Marine. Even Newt Gingrich, a close Trump ally, tweeted that day, "Robert Mueller is superb choice to be special counsel. His reputation is impeccable for honesty and integrity."

Mueller served in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969, was wounded in combat and earned a Bronze Star with a V for valor, a Purple Heart and two Navy Commendation Medals. He got his law degree from the University of Virginia, and after a few years at a white-shoe firm, joined the U.S. Attorney's office in San Francisco. George W. Bush brought him back to Washington to be No. 2 at Justice, and he was sworn in as director of the FBI seven days before Sept. 11, 2001.

In that job for 12 years, Mueller reshaped the bureau to tackle the growing threat of transnational terrorists, a herculean undertaking for an agency that viewed intelligence and national security as secondary missions to beat-level criminal busts. He crossed swords with the younger Bush's White House team, twice threatening to resign over matters of principle: once when Justice found a Bush eavesdropping program to be illegal, and again when Bush ordered him to give back to Congress evidence gathered on Democratic Representative William Jefferson, who was later convicted of bribery, racketeering and money laundering.

For all his professional credibility, however, Mueller's efforts as special counsel have not gone unchallenged. In June, one of Trump's lawyers publicly entertained the idea that the President might fire Mueller because some said the investigation was expanding beyond its original mandate, which in fact is to investigate any crime he may find. That month, Trump tweeted that the Mueller investigation was a "Witch Hunt" and accused some members of the team of bias. By the fall, the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal had called for Mueller to resign.

The pressure has hurt the President more than the prosecutor. Mueller is a lifelong registered Republican, and many in the GOP revere him for his years of service. Two Republican Senators, Thom Tillis and Lindsey Graham, proposed legislation protecting the special counsel from firing, while conservative commentators lambasted Trump for meddling. The heat over the probe may have permanently undermined Trump's relations with his own Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, whose decision to recuse himself from the Russia matters—Sessions had been a member of the Trump campaign—opened the door for Rosenstein's selection of Mueller.

For all the focus on Trump and his inner circle, the Russia investigation is about something bigger than the conduct or outcome of the presidential campaign. The U.S. intelligence community concluded, and still believes, that the primary goal of the Russian operation was to undermine faith in American democracy at home and abroad. Mueller is America's answer to that challenge, the personification of the idea that rule of law remains paramount—even, or especially, when it touches our core democratic processes and our most powerful government officials.

Michael Zeldin, who worked directly for Mueller in Justice's criminal division in the early 1990s, says his old boss can be trusted to shoot straight no matter what he uncovers. "If you've done something illegal that's worth prosecuting, he will find it and he will prosecute you," Zeldin says. "But if you've done nothing that's worth prosecuting, he has the strength of character to decline to prosecute you. That's an important characteristic, especially in a special counsel who has a wide mandate."

No one knows what the special counsel will discover, whether his probe will go further up the chain of power or peter out. What Robert Mueller has made abundantly clear already, however, is that whatever its divisions, the United States remains a nation governed by laws.

-With reporting by Molly Ball/Washington