t was just past midnight on Feb. 28 in the Moscow studios of RT, Russia’s state-funded international television news network, when word of the assassination reached the staff: Boris Nemtsov, a leading figure in the fractious opposition to President Vladimir Putin, had been shot dead a short walk from Red Square. Later that morning, Putin’s spokesman set the tone for RT’s coverage. “What goes without saying,” said Dmitri Peskov, “is that this is a 100% provocation.” His implication was clear: the Nemtsov shooting was staged by Russia’s enemies, not to silence the victim but to discredit the regime he opposed.

t was just past midnight on Feb. 28 in the Moscow studios of RT, Russia’s state-funded international television news network, when word of the assassination reached the staff: Boris Nemtsov, a leading figure in the fractious opposition to President Vladimir Putin, had been shot dead a short walk from Red Square. Later that morning, Putin’s spokesman set the tone for RT’s coverage. “What goes without saying,” said Dmitri Peskov, “is that this is a 100% provocation.” His implication was clear: the Nemtsov shooting was staged by Russia’s enemies, not to silence the victim but to discredit the regime he opposed.

Thus began the latest marathon of spin from the Kremlin’s most sophisticated propaganda machine, beamed out in a variety of languages—including English, Spanish and Arabic—to the potential audience of 700 million people that RT (formerly Russia Today) claims to reach in more than 100 countries. In the hours after the shooting, RT anchors and pundits cast the killing variously as a “huge gift to Putin haters”; possibly the work of “foreign assassins” to provide a “beautiful propaganda shot” for Western officials and media; and, repeating Peskov’s line, “a provocation against the Russian government.”

The coverage did not mention the fears Nemtsov, 55, had expressed in an interview less than three weeks before his murder that Putin could have him killed. It ignored the fact that Nemtsov was preparing to publish an investigation into Russia’s support for separatist rebels waging war in eastern Ukraine. It sidestepped the pattern of more than a dozen murders and violent attacks against Kremlin critics in the 15 years since Putin came to power. And on March 1, when a massive march began in Moscow to protest Nemtsov’s murder—with many carrying signs that read propaganda kills—RT was showing a documentary about American racism and xenophobia.

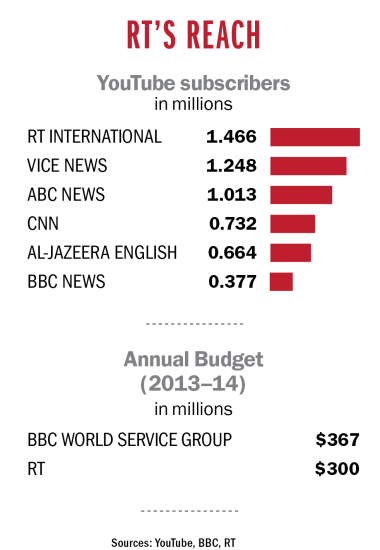

In his death as in his life, Nemtsov’s attempts to promote democracy and pluralism in Russia were nearly drowned out by the barrage of conspiracy theories and misinformation that has turned RT and the Kremlin’s other media outlets into one of the most powerful arms of Putin’s government—at home and abroad. As dissidents in Russia have been demonized by its relentless on-air attacks, so too has the West suffered in an increasingly one-sided propaganda war that has intensified since the conflict in Ukraine flared up more than a year ago. With RT in particular, Putin has created an alternate reality on TV and online—RT generates more YouTube views than any other news channel in the world—that resolutely casts Russia as victim and the West as villain. For Putin’s opponents, whether in Moscow, Kiev or Washington, the Kremlin media machine has real-world impact. It shores up support at home and creates dissent abroad. In the U.K., the channel is the fourth most watched 24-hour news station in the country, beating rivals like Fox News.

Putin founded RT in 2005 with a budget of about $30 million and gradually ramped it up to more than $300 million per year by 2010. (By comparison, the BBC World Service Group, which includes TV, radio and online news distribution, has a budget of $376 million for 2014–15. The BBC’s International Service is the biggest broadcast newsgathering operation in the world.) The network has already gone a long way toward “breaking the Anglo-Saxon monopoly on global information streams,” as Putin instructed it to do during a visit to RT’s brand-new studios in Moscow in 2013. For him this project is about much more than vanity in an era when digital media are, as he unabashedly put it in October, “a formidable weapon enabling the manipulation of public opinion.”

It has proved formidable enough to put the West on the defensive. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry denounced RT last April as a “propaganda bullhorn” for Putin, accusing it of “distorting what is happening, or not happening, in Ukraine.” Western policymakers have increasingly debated the need for a more vigorous response, either with fresh funding for their own media outlets, such as Voice of America, or a new Russian-language channel to fight Putin on his own turf.

But experts warn that getting into a propaganda war with Russia will be self-defeating. The only way to counter misinformation, they say, is to doggedly stick to the facts. The aim of RT is to “inundate the viewer with theories about Western plots, to keep them dazed and confused,” says Peter Pomerantsev, a British expert on Russian propaganda. Trying to counter that RT-type spin with Western counter-spin would only serve to legitimize RT. That would only play into Putin’s hands.

Behind the Camera

argarita Simonyan, the editor in chief of the RT network, places her head in her hands and lets out a groan at the question she has heard so many times before: Does the Kremlin influence her coverage? She admits that her network shows a worldview that is “defined by certain principles expressed by the state, by representatives of the Russian state.” But she claims not to see how that makes RT any less objective than an independent Western broadcaster. “No one shows objective reality,” she says, sitting in her office in Moscow, just across the river from the Kremlin. “The Western media are not objective, reality-based news sources.”

argarita Simonyan, the editor in chief of the RT network, places her head in her hands and lets out a groan at the question she has heard so many times before: Does the Kremlin influence her coverage? She admits that her network shows a worldview that is “defined by certain principles expressed by the state, by representatives of the Russian state.” But she claims not to see how that makes RT any less objective than an independent Western broadcaster. “No one shows objective reality,” she says, sitting in her office in Moscow, just across the river from the Kremlin. “The Western media are not objective, reality-based news sources.”

Simonyan has spent her career at the intersection of journalism and propaganda. In 2002, she got a job as a reporter for state TV in Moscow, assigned to the Kremlin pool, the huddle of journalists that follows and transmits Putin’s every public utterance. Within a few years, she had distinguished herself enough in that role to be given the top job—at the age of 25—at the newly established Russia Today network, which changed its name to RT four years later.

In 2012, when Putin announced his plan to return to the presidency after a four-year term as Prime Minister, Simonyan became directly involved in politics, joining the staff of Putin’s election team in Moscow and helping campaign for his landslide victory—while remaining in her job at RT. Asked the following year how she avoided a conflict of interest between her campaign role and her position as a journalist, she told an interviewer that she wasn’t sure, adding, “I’ve managed.”

At the end of 2013 she was awarded the job of editor in chief of Rossiya Segodnya, the Kremlin’s newly formed media conglomerate. Headquartered in a sprawling complex of gray concrete on Moscow’s Zubovsky Boulevard, the agency consolidated some of the state’s vast holdings in the information industry, including news wires, radio stations and, as of last November, an international multimedia agency called Sputnik, which puts out news in 12 languages, among them Chinese, Hindi and Turkish. Of all those brands, RT is by far the most powerful in delivering the Kremlin’s version of news to the world.

Simonyan, now 34, bristles at suggestions that her media empire is not editorially independent. Is it possible, for instance, that someone from the Kremlin might call her up and demand that she not broadcast a particular story? “How can you imagine such a thing?” she asks, looking genuinely hurt.

And yet on her desk sits an old yellow telephone, a government landline, the sort with no dial pad, the sort usually seen in the offices of senior Russian officials. It is her secure connection, she admits, directly to the Kremlin. What’s it for, then, if not to talk shop? “The phone exists,” she says, “to discuss secret things.”

Conspiracy TV

entral to the RT worldview is the conviction that Western plotting is behind most of the world’s political violence. The terrorist attacks of 9/11? “Probably an inside job,” ran the title of an RT series on the subject in 2009. The Boston Marathon bombing in 2013? “Preparation for new wars and martial law in America,” said British RT host Daniel Bushell on his now discontinued show The Truthseeker.

entral to the RT worldview is the conviction that Western plotting is behind most of the world’s political violence. The terrorist attacks of 9/11? “Probably an inside job,” ran the title of an RT series on the subject in 2009. The Boston Marathon bombing in 2013? “Preparation for new wars and martial law in America,” said British RT host Daniel Bushell on his now discontinued show The Truthseeker.

Along with RT’s frequent coverage of UFO sightings, this type of material attracts a lot of eyeballs online. The videos on RT’s English-language YouTube channel have racked up nearly 1.4 billion views, thanks in large part to RT’s knack for posting raw footage of violence and natural disasters that tends to go viral, drawing more viewers to its political offerings.

In many Western countries, the network has found a loyal following among viewers—from both the left and the right—who are mistrustful of their own governments and wary of prevailing takes on world events. The right-wing fringe in Germany, for instance, has plenty of RT fans, especially among the anti-immigrant movement named Pegida that sprang up last year in the eastern city of Dresden. During Pegida’s marches against what it calls the “Islamization of the Western world,” Russian flags flew alongside German ones.

“We like Russia here,” the movement’s leader, Lutz Bachmann, told TIME after its biggest ever rally in January. “For a stable Europe, you need a friendship with Russia. If we are getting into a war with Russia in Europe, you in the States will laugh about it because you are far away. But we will have destroyed cities.” It was a line that could have come straight from RT’s talk shows, which Bachmann and many of his followers prefer to the mainstream channels in Germany.

Among U.S. audiences, the network boasts of being available to 85 million people, largely through RT America, a U.S.-focused channel RT launched in 2010 and has staffed mostly with American journalists. Its headquarters are in Washington, less than half a mile from the White House. RT says it has been the most popular foreign news network in seven of the largest cities in the U.S. since 2011, citing research it commissioned from Nielsen, a global TV ratings firm. That puts it ahead, in those markets, of the BBC and al-Jazeera America, which is funded by the government of Qatar but has faced fewer accusations of anti-American bias. Though some U.S. conservative groups have called for both RT and al-Jazeera to register as “foreign agents” with the Justice Department, the U.S. Constitution ensures them the same free-speech protections as any other media outlet.

In the U.K., RT is looking to build on its success, including an audience that regular reaches more than 2 million people per quarter, according to the Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board. In October the network launched a U.K. channel based in London that provides local news along with the broadcasts beamed in from Moscow.

RT is seeking—and winning—fans farther afield also. In Latin America, Argentina became the first country last fall to connect RT’s Spanish-language channel into its free-to-air network, making it available to anyone in Argentina with a functioning TV set. During a video conference with Putin to mark the occasion in October, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner summed up the partnership this way: “We are achieving a communication without intermediaries, in order to transmit our own values.”

Many states have tried to match RT’s success. Both China and Iran, for instance, have launched their own English-language, 24-hour news networks, but they don’t have nearly the same reach or broad appeal as RT, which Putin has also turned into a way to strengthen his global alliances. Along with favorable oil deals and shipments of Russian weapons to countries like Syria and Venezuela, Putin can now invite his friends to plug into his media insurgency against the West.

This is a relatively easy sell for the many nations fed up with what they see as pervasive U.S. influence in world affairs. Simonyan calls it a search for alternatives in an era of American decline. “People don’t believe you anymore,” she says flatly, scanning the wall of TV screens that dominates her office, showing CNN and BBC alongside her own broadcasts from around the world. “But they believe us. They believe that our picture of the world is closer to reality.”

War Wounds

eality, however, is not always subject to loose interpretation, as RT has found amid the conflict in Ukraine. The U.S. and its allies have imposed sanctions to punish Putin’s annexation of the Ukrainian region of Crimea and his support for separatists in eastern Ukraine. Combined with a sharp drop in the price of oil, the sanctions have pushed the Russian petrostate to the edge of recession. Worst of all for RT, the value of the ruble, the national currency in which its budget is denominated, has collapsed by almost half, forcing the network to shelve its plans to launch channels in German and French this year.

eality, however, is not always subject to loose interpretation, as RT has found amid the conflict in Ukraine. The U.S. and its allies have imposed sanctions to punish Putin’s annexation of the Ukrainian region of Crimea and his support for separatists in eastern Ukraine. Combined with a sharp drop in the price of oil, the sanctions have pushed the Russian petrostate to the edge of recession. Worst of all for RT, the value of the ruble, the national currency in which its budget is denominated, has collapsed by almost half, forcing the network to shelve its plans to launch channels in German and French this year.

The conflict in Ukraine has also occasionally made it hard for some RT employees to stick to the Kremlin line. One particular challenge for the network came in March 2014, when Putin sent his troops to occupy Crimea. RT broadcast the President’s implausible assertion that no occupation had occurred and that the Russian soldiers fanning out across Crimea were in fact pro-Russian locals who had somehow gotten their hands on Russian uniforms and military vehicles.

That proved to be a distortion of reality too great for some of RT’s journalists. On March 3, 2014, one of RT’s American hosts in Washington, Abby Martin, condemned Russia’s “military aggression” in Crimea during a live broadcast; two days later, her colleague Liz Wahl resigned on air, telling viewers she could no longer be part of a network that “whitewashes” Putin’s actions. At about the same time in Crimea, an RT reporter told TIME that he knew, of course, where the invading troops had come from, but he feared for his job in a shrinking industry if he identified them as Russian soldiers in his reports.

“When there is an ‘accepted truth’ out there and you’re the only ones challenging it, providing alternative perspectives, it can be hard,” says Laura Smith, a Briton and the network’s chief correspondent in London. “Some colleagues haven’t been able to ride it out.”

Talking Back

hat is the west to do in the face of a form of richly endowed propaganda dressed up as journalism that has broad access to international audiences? In Washington, London, Brussels, Berlin and other capitals, policymakers are rushing to find answers as the war in Ukraine worsens and Russia shows no sign of ending its regional bellicosity.

hat is the west to do in the face of a form of richly endowed propaganda dressed up as journalism that has broad access to international audiences? In Washington, London, Brussels, Berlin and other capitals, policymakers are rushing to find answers as the war in Ukraine worsens and Russia shows no sign of ending its regional bellicosity.

In a direct response to Russia’s propaganda efforts against Ukraine, the U.S. Congress passed a bill in July to make the state-funded Voice of America a more direct mouthpiece for U.S. foreign policy, shifting away from its mission of providing uncensored local news in places where it’s hard to find. “We are trying to counter Russian propaganda—and that of our adversaries throughout the world—with one hand behind our back,” said Ed Royce, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, as he urged President Barack Obama to support the legislation.

Closer to the front line in the information war with Russia, European states are considering an even more direct approach: a Russian-language news channel to counter the Kremlin’s domestic networks. Latvia has championed this project within the European Union, largely because ethnic Russians make up more than a quarter of its population and get most of their news from Kremlin-backed TV. The Latvian government’s worst nightmare? An ethnic-Russian uprising like the one in eastern Ukraine, fueled by Kremlin propaganda. “What happens now is that these channels somehow resonate with people’s feelings and emotions and exploit it,” says Viktors Makarovs, an adviser to the Latvian Foreign Ministry. “Our population has been influenced by this.”

But even Latvian policymakers seem to realize the futility of trying to outspin the Kremlin, as critics have cautioned Voice of America against doing if it strays too far. “The easy way would be to create a media financed by the E.U. that would be a Brussels mouthpiece,” says Makarovs. “Which would be the stupidest thing to do.”

At best such a channel would get shouted down by the Kremlin’s loyal chorus of media outlets, including RT, and at worst it would degrade the standards of Western broadcast journalism, eventually making it hard to distinguish between legitimate journalism and RT-like state-sponsored spin. No one understood that better than Nemtsov. Last summer, about eight months before he was assassinated, he appeared on a Ukrainian talk show where one of the guests proposed combatting the likes of RT with an array of Western counter propaganda.

Nemtsov objected. “This would be a road to nowhere, a road to dictatorship,” he said. “You can’t do what Putin does, calling journalists to the Kremlin and giving them orders.” For now, the West seems likely to stick to its journalistic traditions—and trust the viewers to decide.

—With reporting by Charlotte McDonald-Gibson/Brussels

This article appeared in the March 16, 2015, issue of TIME.