Thousands of migrants and refugees remain stranded in Greece

By andrew katz | Photographs by angelos tzortzinis

Issa stood alone in the tree. He wore a dark hoodie, jeans and sneakers. The Kurdish boy, at 11 years old, had perhaps seen more of the world than his parents would have anticipated by that age: a homeland in flames, a treacherous journey over land and sea, a life in a tent not meant to become a home. The roots of the tree on which he stood were firmly planted in Greek soil near Idomeni, the border village that became a flashpoint during last year’s influx of more than 1 million migrants and refugees into Europe.

He was among thousands stranded at a squalid encampment there since officials in Macedonia, the focus of Issa’s gaze, had closed the crossing before his family could soldier on the well-trodden path through the Balkans into Western Europe and Scandinavia. When Issa climbed down, he met the photographer Angelos Tzortzinis. “He sees the future on the tree,” Tzortzinis recalls.

Tzortzinis, who was named TIME’s Wire Photographer of the Year in 2015, has devoted much of the last seven years to chronicling Greece’s economic meltdown. He was born and raised in Egaleo, a working-class suburb of Athens, and has seen his country’s struggles firsthand. He grew up with friends who had moved there from the Middle East; seeing refugees from Syria and Iraq was “like I saw the same people from my past,” he says. It’s that background that influences his perspective: “I am a Greek photographer and I represent the problem,” he says. “I live inside the problem.”

Last year, Tzortzinis turned his lens on Greece’s rise as a waypoint for the world’s most hopeful. He went to the outer islands and picked up freelance work documenting the continental shift. Hundreds of thousands would arrive on flimsy vessels, then be shipped to Athens and the country’s northern region, where they would walk to Macedonia and become another country’s problem. Paralyzed, the E.U. and Turkey struck a deal to curb more ships from coming, and the border with Macedonia closed, stranding thousands in camps.

The European Commission announced on Sept. 10 it would more than double its emergency aid to Greece—providing $129 million via humanitarian groups, voucher programs and cash—toward access to education for children and shelter for families ahead of winter.

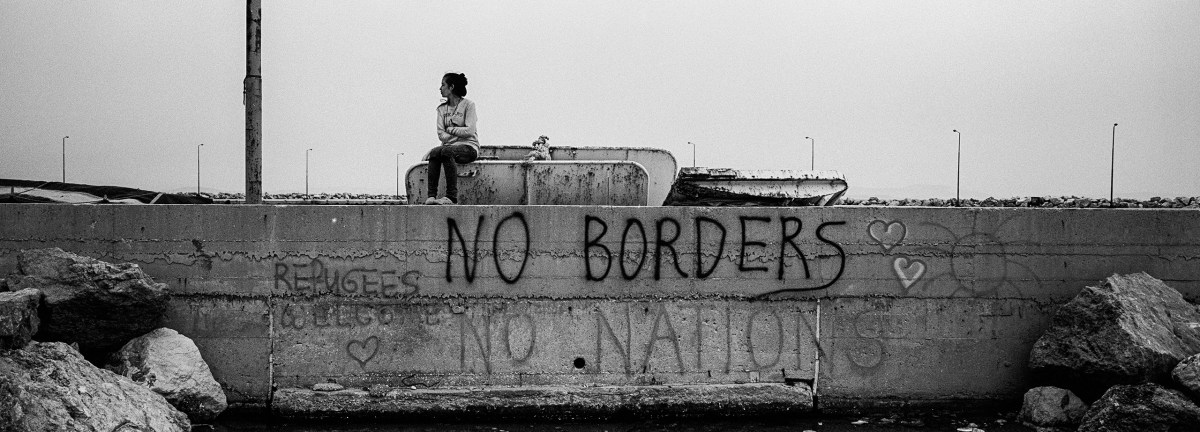

These pictures emerged from Tzortzinis’ personal project about immigration. With support from the Magnum Foundation, he focused on the landscapes that were altered by the movement of migrants and refugees across Greece—and the some 60,000 who remain. With so many images of the deluge of people already out there—focused on the who and what—he often sought “counter pictures,” or ones that focused on the where. Every inch of the frame he fills with his panoramic Hasselblad XPan and 45mm lens is calculated. Over the span of five months earlier this year, Tzortzinis traveled to four locations where the crisis crystallized: the capital, Athens; the disease-ridden camp near Idomeni, and the outer islands Lesvos and Chios, where the majority of boats landed from Turkey.

When Tzortzinis arrived on the islands, he found himself alone. Months earlier, he would have bumped elbows with two dozen or more photographers. “I felt disappointment because the media was not there to cover the situation,” he says, because “the people forgot the story.”

On Lesvos, he photographed one of the main piles of life jackets. “It was haunting because there were a lot of different colors: orange, blue, black. For me it was a difficult scene,” Tzortzinis recalls. “I tried to imagine these people. Some people lost their lives.” The island hosts a graveyard full of tombstones of those who died on the way to Europe.

At the camp near Idomeni, where he spent 14 days, Tzortzinis said people who became stranded began to cut down trees. Each night small bright fires would burn into the dark sky. There, he made a portrait of a woman holding a child in her tent. It brings to mind Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother portrait of an impoverished drought-stricken family in 1930s California. “Three days earlier the government closed the border, but this family believed they would eventually cross,” he says. “I show the disappointment inside their eyes.”

At the Schisto camp near Athens where many migrants from Afghanistan and Pakistan lived, he observed men praying and sleeping in bunk beds at temporary accommodations. One morning before the sun rose, he went to a port nearby. There, he saw a tent sandwiched between shipping containers. “When I saw this picture, I felt depressed, I felt pressure because they were living this way,” he says.

Tzortzinis isn’t sold on the idea of impact from his photography. He sees beauty, not power, in his work. “I want people to see my pictures and read my pictures—not quickly—and to feel the weight of the waiting that the people experience in Greece,” he says. “All of the people are waiting for something. A better life.”

Angelos Tzortzinis is a freelance photographer and stringer with Agence France-Presse based in Greece. He was named TIME’s Wire Photographer of 2015. Follow him on Instagram angelos_tzortzinis.

Andrew Katz, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s International Multimedia Editor. Follow him on Twitter @katz.