When you’re driving across the country with a stash of marijuana in your trunk, you follow the speed limit. You signal when changing lanes. You might even pick a route that skips Colorado, because ever since recreational pot was legalized there, police just over state lines have been on the lookout for anyone ferrying the drug from the area.

But the Colorado-free route from California, where you bought your marijuana, to the Northeast, where you live, presents a curveball. Cruising along I-40 in Arizona, you encounter a border patrol checkpoint. “Good evening, officer,” you say. A German shepherd approaches your vehicle and somehow doesn’t detect the marijuana that’s under a pile of ice in a cooler. As you’re sent on your way, adrenaline pulses through your body. Tears pool in your eyes.

You are, after all, committing at least several state and federal crimes, but when you get home a few days later, it’s business as usual. Three times a day, you or your wife will squirt 2.5 milliliters of marijuana oil into the mouth of your severely epileptic daughter. As a baby, the girl was diagnosed with infantile spasms, a neurological disorder that causes frequent seizures and long-term damage to brain development. Multiple times a day, she’s “like a robot whose plug has been pulled,” says her father. None of the drugs she’s been prescribed have helped and although she can walk, the girl, now 3, does not speak. She goes to a school for kids with special needs.

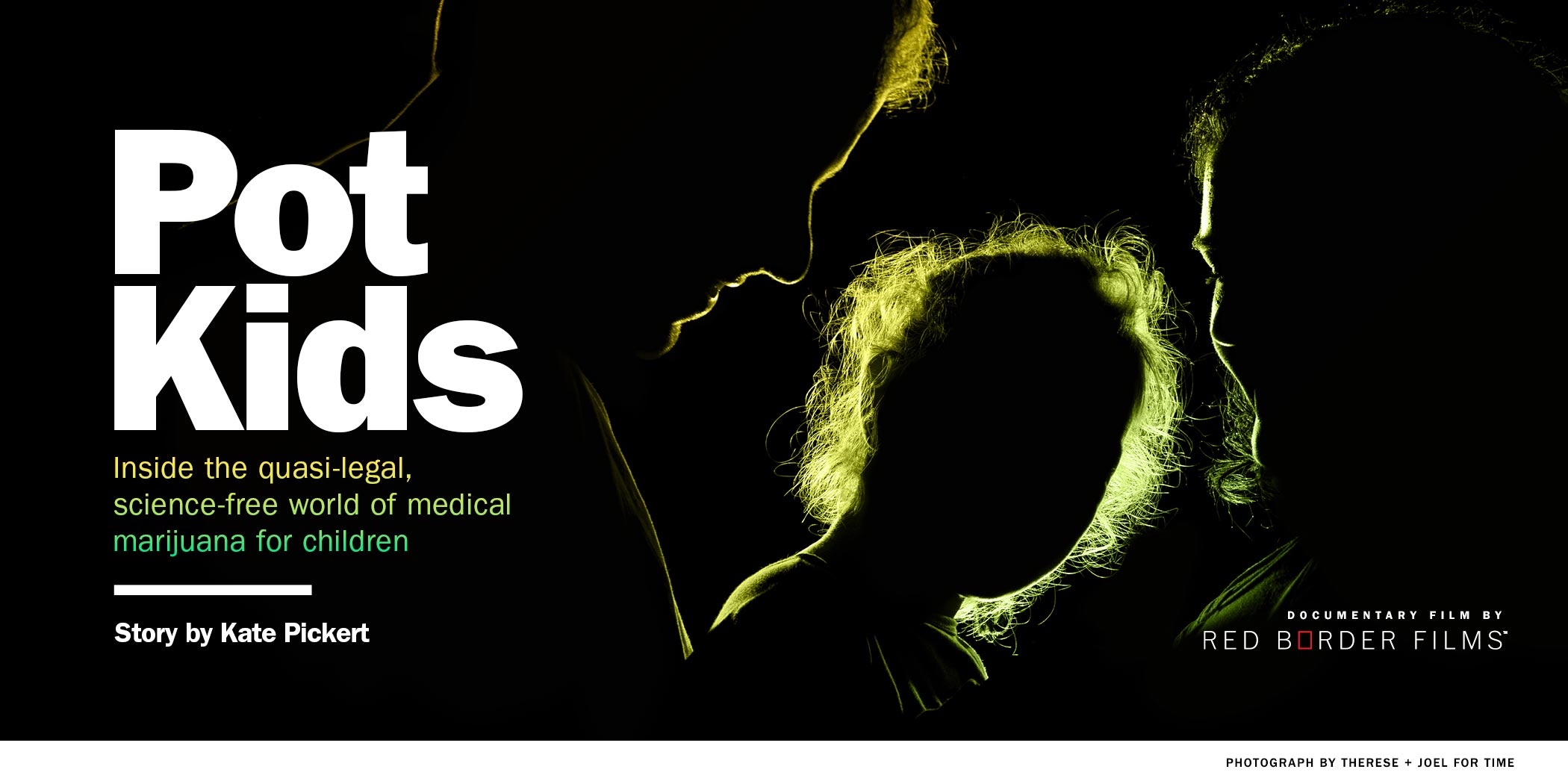

Watch TIME’s feature documentary on children and medical marijuana

The girl was having up to 200 seizures per day when her parents heard anecdotal reports that marijuana could reduce or even stop seizures. Since beginning her marijuana oil regimen earlier this year, the girl’s episodes are down to 30 per day at most, according to her father.

These parents are in good company. About 100,000 U.S. children have intractable epilepsy—a treatment-resistant category of the disease characterized by uncontrolled seizures—and for some of their parents, medical marijuana has gained a reputation as a wonder drug. Fueled by success stories on Facebook and family blogs, these parents are acquiring marijuana through quasi-legal and illegal means, giving their children a derivative oil low in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which causes psychoactive effects, but high in cannabidiol (CBD), one of the hundreds of other compounds found in the plant.

And yet there is little science about the safety or efficacy of treating children with CBD. Medical marijuana is legal in 23 states, but federal law still classifies the plant as a Schedule 1 drug, “with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” according to the Drug Enforcement Agency. (Heroin and LSD are also Schedule 1 drugs.) This means that, even though doctors and researchers have suspected for decades that some compounds in marijuana might effectively treat epilepsy and other hard-to-cure conditions, independent clinical trials that include human subjects—let alone minors—are scant and require approval from three separate federal agencies.

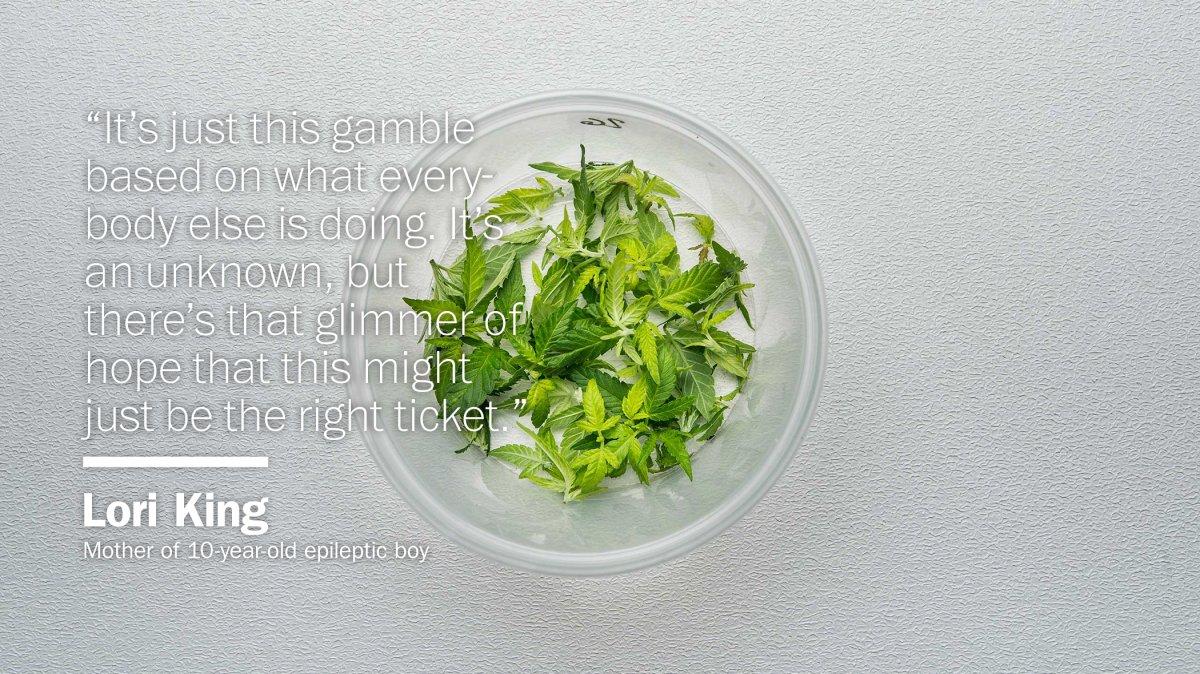

Since 1999, these agencies have approved just 16 independent studies of medical marijuana on humans. The lack of research presents a kind of catch-22: Without much scientific study of marijuana, the government has been unwilling to recategorize the drug. But the categorization as a Schedule 1 drug makes testing it on humans extremely difficult. This also presents parents with little expert advice. “The only guidance we were getting was the community on Facebook,” says Lori King, the mother of an epileptic 10-year-old boy whom she’s treated with marijuana oil since 2013.

The little research that does exist raises questions about the effectiveness of CBD therapy for kids. A recent study, for instance, found that epileptic seizures were significantly reduced in just a third of children studied. Experts are also concerned that in a largely unregulated business, contaminants like pesticide residues and molds could lead to adulterated versions of an otherwise potentially low-risk drug.

The little research that does exist raises questions about the effectiveness of CBD therapy for kids. A recent study, for instance, found that epileptic seizures were significantly reduced in just a third of children studied. Experts are also concerned that in a largely unregulated business, contaminants like pesticide residues and molds could lead to adulterated versions of an otherwise potentially low-risk drug.

“All of a sudden you have these parent groups, which traditionally you’d think would be in opposition to any kind of liberalization of marijuana policies, and they have become the biggest advocates in favor of access,” says Amanda Reiman, manager of the marijuana law and policy unit for the Drug Policy Alliance.

Some of these parents are hoping pot can help where mainstream medicine has failed. Epilepsy costs individuals and institutions $15 billion a year. It is far more common than autism, multiple sclerosis or a host of other neurological disorders. And it kills more Americans every year than breast cancer—and yet the disease receives just 20 percent as much research funding from the National Institutes of Health. What’s more, a third of people with epilepsy have an intractable drug-resistant type.

“We’ve introduced a dozen new drugs in the past 20 years, but it’s not clear we’ve made a significant advance in the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy,” says Dr. Orrin Devinsky, head of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at New York University. “We have failed as a scientific and medical community.”

In the meantime, parents admit they are, in effect, experimenting on their children. Some of them do so with a doctor’s help, tracking how the compound interacts with other drugs and measuring progress over time. But just as often, it seems, parents are going it alone.

The parking lot of Noho’s Finest, a medical marijuana dispensary in a gritty industrial area of the San Fernando Valley, is packed most days. From open to close, customers, most of them men, parade into the emporium where everything from bud to THC-laced cookies and pipes are for sale.

At the edge of the busy parking lot, up a plywood ramp and behind a black metal door, there’s an office belonging to Realm of Caring’s Ray Mirzabegian, the go-to guy in Southern California for medical marijuana as a treatment for epilepsy.

Inside, Mirzabegian, a former optician, plays New Age music on a loop and the iPhone on his desk buzzes every few minutes with text messages. He arrived at his current profession after personal experience convinced him marijuana could better curb seizures than anything in mainstream medicine.

Mirzabegian’s daughter Emily had her first seizure when she was five months old. By the time she was four, she was having hundreds of seizures a day. “Our lives were 60 percent in the hospital for years,” says Mirzabegian. Each seizure a child has can cause damage to the developing brain. Emily had been fluent in English and Armenian, her parent’s native language, until one day, around age 6, “It was like somebody pressed the mute button,” says Mirzabegian.

Over the years, Emily has been prescribed 12 separate medications—none seemed to help and most caused side effects, including depression, vision loss, insomnia and lethargy that left her “sitting on the couch in a vegetative state,” says Mirzabegian. The family tried a ketogenic diet, which consists largely of fat, as well as acupuncture and Chinese medicine. They sent Emily’s medical records to doctors in France and Iran, and even flew to the Dominican Republic where a doctor injected Emily with a pink liquid he claimed was filled with stem cells that would cure her epilepsy. The cost: $30,000 in traveler’s checks. “We were so desperate we even went back for a second round,” says Mirzabegian.

Over the years, Emily has been prescribed 12 separate medications—none seemed to help and most caused side effects, including depression, vision loss, insomnia and lethargy that left her “sitting on the couch in a vegetative state,” says Mirzabegian. The family tried a ketogenic diet, which consists largely of fat, as well as acupuncture and Chinese medicine. They sent Emily’s medical records to doctors in France and Iran, and even flew to the Dominican Republic where a doctor injected Emily with a pink liquid he claimed was filled with stem cells that would cure her epilepsy. The cost: $30,000 in traveler’s checks. “We were so desperate we even went back for a second round,” says Mirzabegian.

Meanwhile, the family met with eight neurologists, eventually finding Raman Sankar, chief of pediatric neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who diagnosed Emily with Dravet Syndrome, a type of epilepsy that, with related causes, kills up to one-fifth of sufferers before age 20.

One night, on a Discovery Channel show, of all places, Mizabegian learned of a father giving medical marijuana to his epileptic son. He was intrigued. Mirzabegian went to a doctor, claimed he had chronic headaches and got a medical marijuana recommendation, allowing him to buy the drug in California.

The first strains he tried on Emily didn’t work, but he later learned, via a documentary on CNN, about a family in Colorado called the Stanleys who were growing Charlotte’s Web, a kind of marijuana they said was effective against epilepsy. Mirzabegian decided to give pot another shot, and with the Colorado marijuana, he says, the results were astounding.

Nearly two years after she began a three-times-a-day treatment plan, Emily is down to four seizures per month and is off nearly all the prescription drugs. She loves to swim and go to Chuck E. Cheese. She’s still developmentally behind her peers with the verbal skills of a two year old, but she is waking up to life for the first time since she was an infant, Mirzabegian says.

He was so impressed with the results he decided to go into business with the Stanleys. Mirzabegian became their first licensee outside of Colorado.

Mirzabegian now has his own facility, and the oil he gives Emily is from the plants he grows himself; he sells the rest to parents who visit his office. Demand for Mirzabegian’s product is fierce, with a waiting list of 1,000 families. Although other dispensaries sell CBD-rich oil and charge prices that can run into the thousands of dollars per month, Mizabegian charges 5 cents per milligram of CBD, with dosages that vary based on the child’s weight. He says he is not yet turning a profit.

Among the patients who came to Mirzabegian’s office on the days I visited was the mother of a severely developmentally delayed 5-year-old boy who weighs 20 pounds. She paid $65 for a month’s supply of Charlotte’s Web. There was also a single mother who lives in fear that her son’s doctor, who opposes the use of medical marijuana in place of pharmaceutical drugs, might report her to child protective services. The boy has intractable epilepsy and severe cognitive and physical delays. “There’s no quality of life. This is like living death,” the mother says later. “He’s so beautiful and sweet, but it’s just heartbreaking.”

One by one, Mirzabegian interviewed each parent, jotting down notes about their kid’s medications and writing up dosage charts. During appointments, he also talked about Emily, who all the parents knew of through the various Facebook support groups Mirzabegian runs. “I’m there with you,” he tells them. “We’re all in the same boat.” Mirzabegian strongly recommends his customers undertake a CBD treatment plan in cooperation with a neurologist.

During one visit, Mirzabegian recommended increasing the CBD dose for Lori King’s son Emeric, who had his first seizure at age 4. Even with his current regimen, which costs $147 per month, King says Emeric is “more present and totally more aware. It’s like he’s waking up from a groggy sleep he’s been in for years.”

Despite the change, King says she’s still not completely at ease giving her son CBD oil. “It’s just this gamble based on what everybody else is doing,” she says. “It is an unknown, but there’s that glimmer of hope that this might just be the right ticket.”

“We don’t actually smoke weed,” says Joel Stanley, the eldest of six brothers working in the family’s medical marijuana business in Colorado. With backgrounds in engineering, business and forestry, the Stanleys started growing medical marijuana in 2009 and opened two dispensaries in Colorado Springs the following year, motivated, they say, by a desire to help sick people. The business opportunity was also alluring. Colorado’s current medical marijuana industry brings in some $30 million per month in sales.

Shortly after they got into the business, the Stanleys stumbled upon a strain of marijuana with a high concentration of CBD but very little THC—the compound that gets you high. They called the plant Hippie’s Disappointment and didn’t bother selling it. But in 2012, the mother of a girl with intractable epilepsy approached them, asking for CBD-rich oil. For the girl, Charlotte Figi, the results were remarkable, according to her parents. Charlotte went from hundreds of seizures per day to almost none. Once a writhing, immobile, non-verbal child, she suddenly began walking and talking. The Stanleys renamed the strain Charlotte’s Web.

After the CNN documentary they were featured in—which is controversial among pediatric neurologists—the brothers were inundated with requests for the drug, which at the time was only available in Colorado, where medical marijuana has been legal since 2000 and where recreational marijuana was legalized in 2013. The brothers, who sell Charlotte’s Web at the same price as Mirzabegian—5 cents per milligram—say they have a waiting list of more than 12,000 families, with many relocating to the state to access the product. Five cents a milligram may sound like nothing, but the 17 acres of the strain they harvested in September are poised to produce $23 million worth of oil. (Joel Stanley says the brothers have incurred large debts on lab equipment needed to make their oil, among other infrastructure, and they plan to reinvest the windfall into further expansion rather than pocket the money.)

Meanwhile, to eliminate a chunk of their waiting list and lower costs, the Stanley brothers have decided to test the limits of existing drug laws. They still sell THC-rich pot through their medical marijuana dispensaries, but are now calling Charlotte’s Web something else: “hemp.” The plant is less than 0.3 percent THC, which meets the federal legal definition of hemp and mirrors concentrations of hemp oil already available in U.S. grocery stores that is imported from abroad. Calling the plant “hemp” means the Stanleys can grow far more of it and, they think, legally ship Charlotte’s Web across state lines, with the first bottles of oil scheduled to leave Colorado in November. Under a federal law proposed in June by Republican Rep. Scott Perry of Pennsylvania, making and shipping CBD-rich oil within the U.S. would be explicitly legal. For now, however, shipping domestically produced hemp oil from state to state is, at best, a legal gray area.

“If we can operate in that gray area to help a bunch of kids who are out of options, so be it,” says Joel. The worst case scenario: their entire supply of Charlotte’s Web is seized, the thousands now receiving the medication are cut off and the Stanleys go to jail. “The first few years in this industry, I had nightmares every night of my kids watching me dragged out of the house in handcuffs,” says Joel. “But after we saw Charlotte and all these patients’ successes, it just became very real that you are living a life worth living and you are doing the right thing.”

Beyond the legal perils, many doctors across the U.S. say there’s another hurdle the Stanleys and other growers must clear before CBD should be widely available: proof that it works and that it’s safe.

If there’s a ground zero for the collision of kids on pot and the medical establishment, it’s Children’s Hospital Colorado in Denver. The facility sees more children treated with medical marijuana, including Charlotte’s Web, than any place in the country, according to Dr. Amy Brooks-Kayal, the hospital’s chief of pediatric neurology and a professor at the University of Colorado.

Brooks-Kayal, who will become president of the American Epilepsy Society in December, is among those worried about the unintended consequences of giving CBD oil to kids. “Some of the anecdotal reports are quite exciting,” says Brooks-Kayal, “but really there is no good clinical information on the effectiveness of any form of marijuana for the treatment of epilepsy.” It’s not just the lack of reliable science on how medical marijuana works that troubles Brooks-Kayal. New unpublished research conducted at Children’s and provided, in summary only, to TIME suggests that many of the epileptic children receiving medical marijuana are not benefiting from the drug at all.

In a small study of 75 children receiving CBD-rich oil and being cared for at Children’s, researchers report in the study summary that about one-third had a reduction in seizures exceeding 50 percent, the standard threshold for treatment efficacy in epilepsy. Among those whose seizures were reduced by CBD, researchers reported that the children’s electroencephalographies (EEGs), which measure electrical activity in the brain, remained the same—which is not uncommon but concerns Brooks-Kayal all the same. The study found that families who moved to Colorado for access to medical marijuana were three times as likely to report at least a 50 percent reduction in seizures, suggesting placebo could be a factor.

The Children’s study did not note the kind marijuana oil children were being given, which makes replicating the findings in future research—the ideal with any scientific research—impossible. This brings up another conundrum: the popularity of Charlotte’s Web has some parents scrambling for any medical marijuana touted as having high levels of CBD, even if it’s less or more potent, or includes contaminants that could be dangerous for children to ingest.

“Some days I think it completely helped and other days I feel like it’s no different,” says Carrie Baum, a Los Angeles-area mother who tried CBD-rich oil on her 6-year-old son after an anti-epilepsy drug turned him into “a small zombie child,” as she puts it. “We’re committed to it enough to keep trying and keep working through it. What else is there?”

A soon-to-be-published online poll conducted by the journal Epilepsia shows that among neurologists, including those who specialize in epilepsy, 34 percent said there was sufficient safety data on medical marijuana. Among non-doctors, the figure was 96 percent.

Some science may soon be forthcoming. Earlier this year, British company GW Pharmaceutical launched an FDA-approved a trial of a marijuana-derived CBD drug called Epidiolex. The trial is being conducted at NYU, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and soon, UCLA.

Researchers at NYU, led by Devinksy, and UCSF reported in June that of 27 patients treated with Epidiolex for three months, 13 experienced at least a 50 percent reduction in seizures. Four were seizure-free after 12 weeks. These results, while exciting, are lower than the 70 to 80 percent efficacy rate the Stanleys and Mizabegian have reported among the pediatric epilepsy patients taking Charlotte’s Web—albeit without the kind of scientific rigor that pharmaceutical drugs need to go through. The Epidiolex trial results were also muddied by the fact that patients in the trial also take other prescribed pharmaceuticals. Under GW Pharmaceutical’s timeline, FDA approval could come in late 2016 or early 2017.

One of the Epidiolex study subjects turned up at Mirzabegian’s office on one of the days when I visited. A mother of a 5-year-old epileptic girl brought a bottle of Epidiolex with her and said the drug had not been effective. Unlike Mirzabegian’s thick black oil, the Epidiolex looked like water and contained additives that made it smell like strawberries. Mirzabegian was fascinated. “How do they get it so clear?” he wondered, turning the bottle around in his hands.

Mirzabegian welcomes the research—but it won’t change what he does in the meantime. “You can bring studies that were done in universities—which is great, we need that to happen,” says Mirzabegian, “but I would never discount the research that comes from thousands of parents who have the same exact problem who come together and share their stories.” Doctors and scientists, he says, “have no right—especially when they know everything in their toolbox has failed—to come and point fingers and say there is no evidence, there is no study, no this or no that. That’s their job.”

There’s a race afoot among those trying to bring non-FDA-approved CBD-rich oil to mass market and the clinical drug trials now underway. In addition to the Stanleys, companies peddling natural supplements are also jumping in, along with new marijuana-centered businesses betting that domestically produced hemp and CBD will soon be a multi-billion dollar industry. In 2013, Josh Stanley, the former spokesman for Charlotte’s Web, left the family business to start a non-profit organization and a for-profit company planning to sell CBD-rich oil as a nutraceutical, a product category that falls outside the regulatory rules of the FDA.

Such an approach troubles UCLA’s Sankar, who has worked as a paid consultant to a pharmaceutical company working to develop a synthetic form of CBD. Sankar treats scores of children taking CBD, Emily Mirzabegian among them. “If I’m writing a prescription, I’m going to write it for something that’s approved by the FDA,” he says. Taking a drug out of the FDA approval process because it’s easier to bring to market through a loophole means far less testing is required to measure purity and effectiveness. Mirzabegian says this is a double standard, pointing out that of the 12 drugs prescribed to Emily, eight were not approved by the FDA for use in children.

Although many of the parents who spoke to TIME insisted on anonymity, none refused to be interviewed. In the absence of medical guidance or research, these parents swap tales and experiences on Facebook pages and online discussion boards, eager to share miraculous stories of how their children and families have been transformed by CBD.

The Northeast father who drove marijuana oil across the country says his daughter is now playing and interacting with others for the first time in her life. She is learning to pull up her own pants, take off her own shoes and speak. On a recent trip to a Disney store, she accidentally knocked an object off a shelf and her parents were shocked that she stopped and tried to put it back in place. Even typical toddler temper tantrums have been a welcome sight. “She used to be on so many different drugs that she would just be dragged along wherever we went,” says her father.

The girl is on the waiting list for Charlotte’s Web and her parents are hoping the Stanleys’ plan to ship their product from Colorado to other states pans out. But if it doesn’t, they’re planning another cross-country car trip to stock up on the oil when their supply runs out.

“When it comes to medical marijuana, nobody knows what happens long term,” says the girl’s father. “But since she was nine months old, we’ve had to make choices about her life that we haven’t wanted to make. We put her on a steroid, which bloated her to no end. She was cranky and it delayed her. We put her on anti-seizure drugs that had their own side effects.” These included potential loss of eyesight, liver damage and, in the case of one drug, risk of death.

“We’re doing the best we can with all these decisions,” says the father, “but all these decisions stink.”