The shooting death of Michael Brown, and the violence that has followed, have only made the town’s problems worse

Ten days after Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, died in a storm of bullets from the sidearm of officer Darren Wilson–and after nine nights of protests marred by spasms of violence–the authorities in St. Louis County announced plans to lay the facts of their investigation before a grand jury. FBI agents had been busy behind the scenes, interviewing witnesses. Forensic experts for the federal government and local police had pored over the evidence collected in their separate but cooperating inquiries. No fewer than three autopsies had been performed: one for the locals, one for the feds and one on behalf of Brown’s family. But no testimony or trail of clues could alter the fact that a white policeman had killed an unarmed African American. For a lot of people, that was the only thing that mattered. Something was ruptured in Ferguson, Mo., when “Big Mike” hit the pavement, revealing an ugly fault line.

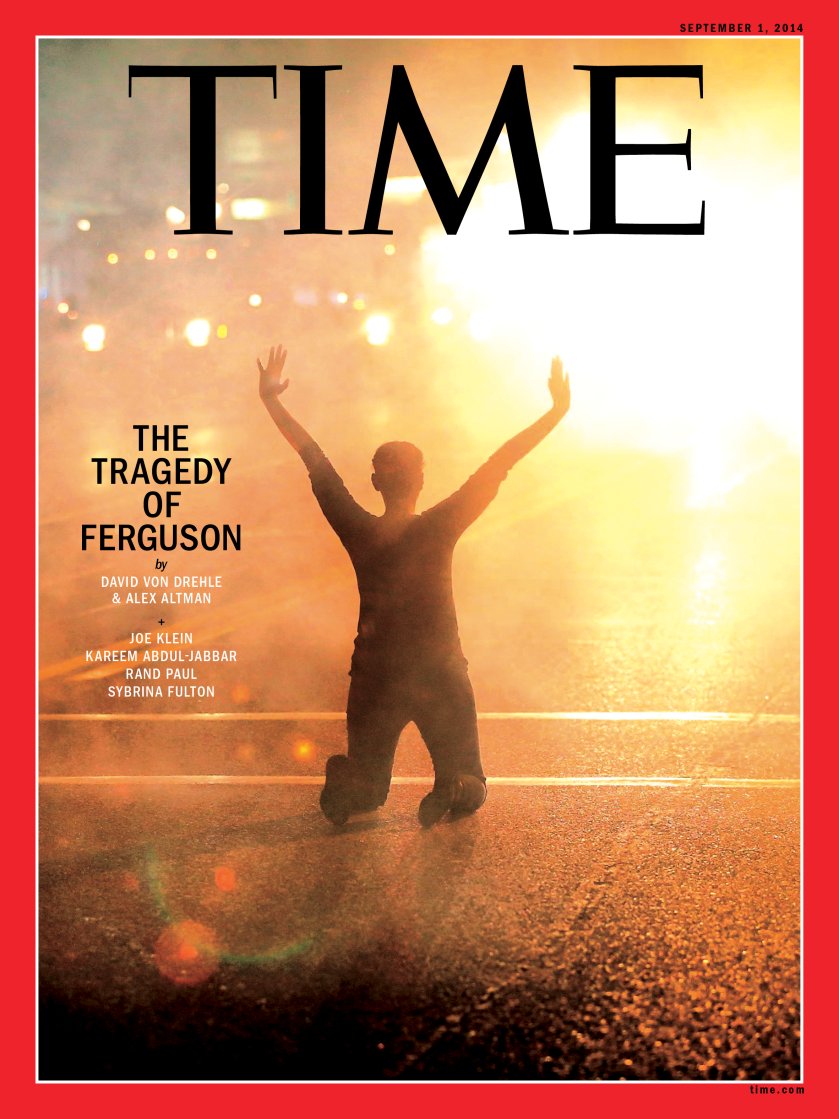

Ferguson is no longer just the name of a township. It has become a stern lesson in the value of public trust–the city learned too late that the well was dry–and a painfully familiar one. When the shots rang out on Aug. 9, the usual figures assumed the customary positions. Al Sharpton? Check. Cable-news anchors? Check. Activists in Guy Fawkes masks? Check. The flames, the clouds of tear gas, the righteous anger of the protesters: What was live and what was videotape? The dead youth. The ruined cop. The clashing accounts of a few lethal moments. We’ve been here before–and failed to learn the lessons.

Virtually no one connected to the tumult–whether by proximity, profession or ideology, by happenstance or choice, in the flesh or digitally–escaped the nightly melees without paying some sort of price. Local parents scrambled to arrange child care and meals when public-school classes were canceled. Neighborhood workers like Brian Moore paid in lost salary because their employers closed early every night.

For Americans watching from a distance, the price was psychic: another crisis in which leaders offered more angst than answers. The mayor of Ferguson blithely insisted that his city is racially harmonious–pay no attention to the broken glass, the scorched storefronts and the data clearly showing that a mostly white police force has targeted blacks for a disproportionate number of stops and searches. Missouri Governor Jay Nixon, after a squabble with the chief prosecutor of St. Louis County, called in the National Guard without so much as a courtesy call to the White House. Vacationing President Barack Obama struggled to avoid taking sides in a case that grew murkier by the hour. Even the would-be hero of the sad saga failed in his arguably hopeless mission. Missouri highway patrol captain Ronald Johnson, an African American who grew up near Ferguson, was pushed into the fray by Nixon after the situation had already gone bad. Calm, compassionate and brave, he tried to pacify the scene by shaking hands, listening, even marching alongside the protesters. But militants turned his olive branch into a torch.

This time, perhaps, there was more willingness to admit to the underlying problem. As Republican Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky wrote on TIME.com, to a rare burst of bipartisan assent, “Given the racial disparities in our criminal-justice system, it is impossible for African Americans not to feel like their government is particularly targeting them.” The elected and civic leaders of Ferguson could not escape the realization that whatever the town’s problems have been in the past, this turmoil only made them worse. The law-abiding protesters who marched daily in Ferguson were powerless to suppress the opportunistic violence flaring after nightfall. The police and National Guard summoned to pacify the streets were helpless to find a balance between standing tough and standing down. With poverty rising steeply in nearly every neighborhood, Ferguson needs jobs. But what employer is now more likely to move to town? Ferguson needs the middle-class and stable working-class families, black and white, who join the PTA and coach the basketball clubs and plant the flower beds. But those families won’t soon forget the maze of police barricades and fleets of television trucks–or the feeling of being trapped in their homes while militants fired guns and police, in response, filled the night with tear gas.

Anita Matlock, a 20-year-old certified nurse assistant, is breaking her lease to move out of Canfield Green, the beige-and-brown three-story apartment complex that fronts the street where Brown was shot. “It’s too disruptive,” says her mother Yvonne Matlock. “She can’t get in. Can’t get out. Can’t sleep.” Ron Henry, from the nearby town of Florissant, is less inclined to move in. He says his fiancée Clarissa and toddler Ron Jr. had automatic weapons pointed at them by police while they tried to leave his grandmother’s apartment near the center of the conflict. “Rioting,” Henry says, “is the voice of the unheard.” On the other hand, he asked, “Does my 3-year-old son need to get gassed?”

Two Versions

At the heart of it all lay two or three minutes just after noon on Saturday, Aug. 9, a fatal span that brought Brown and Wilson together on a stretch of Canfield Drive. According to Brown’s friend Dorian Johnson, the two young men were walking in the street when Wilson rudely ordered them onto the sidewalk. When the pair didn’t immediately comply, Johnson said, Wilson put his car in reverse, pulled up next to Brown and grabbed him. A struggle ensued; a shot was fired; the pair took off running, Johnson claims, with Wilson in pursuit, firing more shots. Other witnesses sympathetic to Brown alleged that he was shot in the back or while on his knees in a posture of surrender.

The officer’s version of events is more difficult to ascertain. Police say he was injured in an altercation preceding the shooting. According to U.S. Attorney Richard G. Callahan, Wilson’s statement–along with the rest of the evidence collected in the investigation–must be kept secret for now, despite calls from protesters and the media for answers. “The modern 24-hour news cycle hampers law enforcement’s ability to conduct a successful investigation,” Callahan told TIME, because hasty and partial release of information can taint the testimony of witnesses.

“While the lack of details surrounding the shooting may frustrate the media and breed suspicion among those already distrustful of the system, those closely guarded details give law enforcement the best yardsticks for measuring whether witnesses are truthful,” Callahan said. “Without those yardsticks, an investigation becomes more of a guessing game or popularity contest than a search for the truth.”

Instead, the details of the shooting will be presented to the St. Louis County grand jury–a process that bogged down in controversy even before it got started. The man responsible for the case, St. Louis County chief prosecutor Bob McCulloch, is the son of a white policeman killed in the line of duty by a black suspect. Even the county executive, Charlie Dooley, doubts McCulloch’s ability to weigh this case dispassionately. Dooley urged Governor Nixon to appoint a special prosecutor. But that was not to be. Nixon decided instead to issue a statement that virtually demanded an indictment of Wilson. “The democratically elected St. Louis County prosecutor” has “a job to do,” Nixon wrote. Namely, “a vigorous prosecution.” The “obligation to achieve justice in the shooting death of Michael Brown must be carried out thoroughly, promptly and correctly.”

With no official findings to mull, the public was left with partial disclosures from friends, relatives and investigators claiming to speak for Brown and Wilson. Famed former New York City medical examiner Michael Baden performed an autopsy on behalf of Brown’s family. He said he found wounds indicating that at least six bullets hit Brown–including the fatal shot to the top of Brown’s skull. But he could not say whether the wounds were consistent with claims that Brown’s hands were up in surrender. Baden found no signs of a struggle on the body of the dead youth, he reported.

On Wilson’s side, local police buzzed with a rumor that the officer had a broken bone where Brown had punched him in the face. Shades of Trayvon Martin. There was enough uncertainty about the facts at the highest levels of government that the President warned against drawing premature conclusions. “I have to be very careful about not prejudging these events before investigations are completed,” Obama said gingerly.

An Absence of Trust

Meanwhile, each night in Ferguson was a new struggle to restore order to the wounded township, and each subsequent morning a new mess to clean up. In the glare of the August sun, volunteers picked up spent gas canisters. Ferguson became a magnet for troublemakers from every point on the compass, from as near as next-door St. Louis and as far as California and New York. They seeded themselves in the ranks of peaceful protesters and in the throngs of visiting reporters, and no one could predict just when one of them would brandish a gun or fling a bottle. The nights began to blend into one another, and it wasn’t clear how the drama would end. “We’re ready to die!” a voice called one night as rocks and bottles and gunshots provoked a wave of tear gas. Another voice answered. “They’re armed–we’re armed! Let’s do this!”

When trust is absent, it leaves a peculiar vacuum, one that feeds flames rather than starves them. A sign of this absence might be seen in a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press: 80% of black respondents said Brown’s death “raises important issues about race,” but among whites, a strong plurality dismissed the race angle as exaggerated. The lack of trust between police and civilians was apparent in the widespread revulsion at the militarized appearance of armor-clad officers brandishing rifles at bare-chested, sign-waving protesters. But when the cops tried a lighter touch and the result was more looting and arson, that was criticized too. “It doesn’t make a difference what decision you make,” one St. Louis County officer told TIME. “It will be wrong.”

Responsibility for restoring the peace fell in large part to community volunteers. A scene on Aug. 18–Brown was killed on Aug. 9–revealed both the courage and the limits of this strategy. An edgy quiet had prevailed until about 9:30 p.m., when a clutch of agitators surged from an otherwise peaceful crowd toward a line of police. Bottles flew. As the police gathered their riot gear and donned their gas masks, volunteers rushed forward to plead with the cops to hold off. They linked their arms to form a human barricade. Placing themselves between the rioters and the police, they stood firm. “Why are you doing this to us?” one civilian peacekeeper screamed at the advancing mob. For a moment, this plaintive question seemed to bring everyone up short; it captured so concisely the helplessness and exhaustion and demoralization of Ferguson’s situation. But then another bottle arced overhead and smashed on the street, and a new wave of chaos was unleashed.

Healing the Breach

If anything useful can be found in the wreckage of Ferguson, it is the chance for communities across the country to do some serious soul-searching. What is the relationship between police and the public in the place where you live? One lesson of Ferguson must surely be that the time to stop a riot is before it starts.

Asking how will lead smart city officials to the desk of Tom Tyler, a professor at Yale Law School, whose years of research into the psychology of public trust make him the guru of police relations with the people they serve. In an interview with TIME, Tyler said Ferguson is hardly the only American city where police have a potentially explosive credibility problem. “If you survey the public on the question of trust in the police, you will find an enormous racial gap. This has been true for decades,” Tyler said. “African Americans are 20% to 30% less likely to trust the police–and this gap is not diminishing. It’s not going away, no matter what policing strategy is in vogue. The long-term solution would be to start taking this distrust seriously.”

Tyler’s research has shown that the foundation of public trust is respect. Police departments that demonstrate, day in and day out, an attitude of respect for the public they serve are rewarded with trust and cooperation. For example, two large surveys of New Yorkers conducted by Tyler and a colleague found that nothing has a more positive effect on the public’s view of police than a belief that the police exercise their authority in an evenhanded way. “Yet we hear from African-American young men that they aren’t treated fairly,” Tyler said. “They feel disrespected by police, harassed, singled out for stops even though they aren’t doing anything wrong. Police don’t approach them with an attitude of respect. They don’t calmly explain why they are doing what they’re doing. They are seen as trying to dominate rather than serve and protect.”

Ferguson has dramatized just how counterproductive this is. According to Tyler’s research, what America has witnessed in the tragedy and ruin of that unremarkable township is exactly what the data would predict. Attempts by the police to dominate a tense situation tend to escalate rather than suppress violence. Remarkably, even guilty suspects are more likely to cooperate with police when they sense respect rather than intimidation in the attitude of the arresting officer.

This attitude can be taught. When police in training see his data proving that officers are actually safer when they take a less intimidating approach, they come around quickly, Tyler said. It can also be supported by new technologies like body-mounted video cameras that record every encounter police have with the public on patrol. When police in Rialto, Calif., a midsize suburb east of Los Angeles, performed a yearlong experiment with body cams in 2012–13, they found that the devices produced a 59% drop in the use of force by city officers and an 88% decline in the number of complaints filed by members of the public.

Even so, years of study have persuaded Tyler that the crisis of trust goes deeper than technology or practice alone can reach. “It would be wonderful to imagine that there would be such an easy fix to a long legacy of police being misused as an instrument of domination,” he said. A way forward will require all of the above: changes in training, technology and tactics. Most of all, it will take changes of heart. We seem to be better at snuffing out trust than at kindling it lately. In Ferguson we have seen where that leads.

–WITH REPORTING BY ZEKE MILLER AND ALEX ROGERS/WASHINGTON AND JOSH SANBURN/NEW YORK