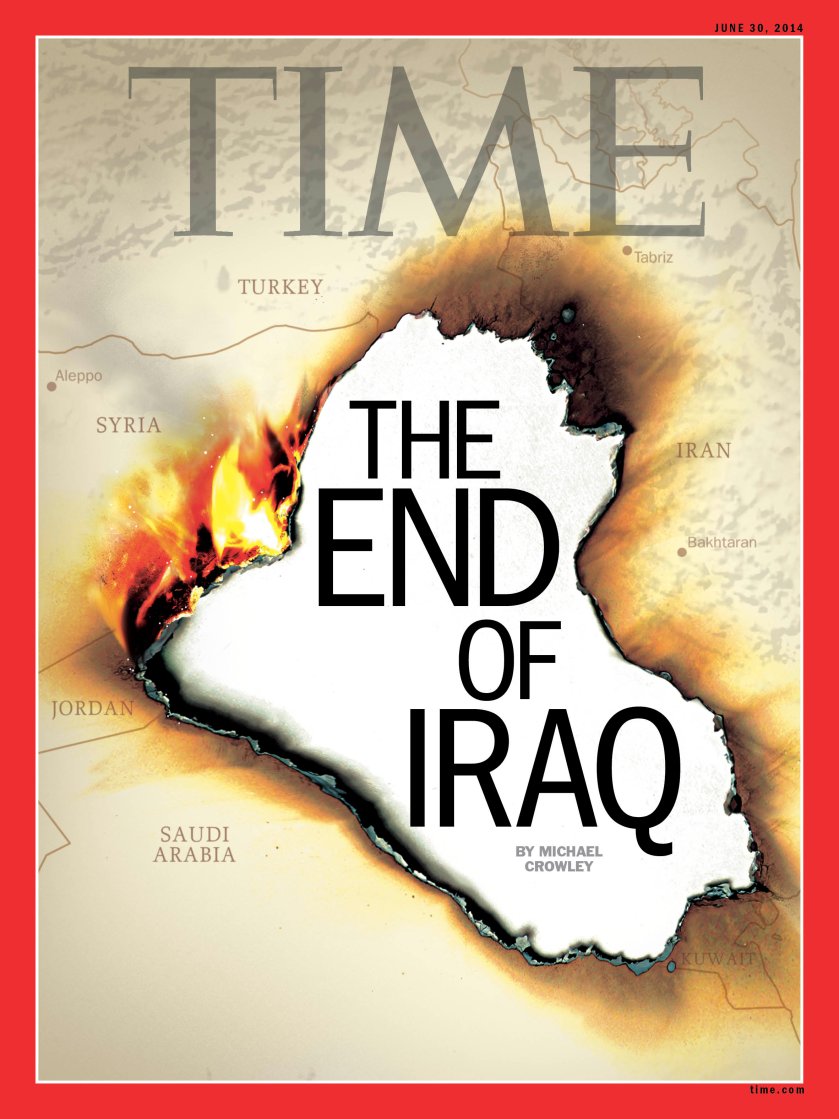

The sudden military victories of a Sunni militant group threaten to touch off a maelstrom in the Middle East

As the brutal fighters of the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) rampaged through northern Iraq in mid-June, a spokesman for the group issued a statement taunting its shaken enemies. Ridiculing Iraq’s Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki as an “underwear merchant,” he warned that his fighters, who follow a radical strain of Sunni Islam, would take revenge against al-Maliki’s regime, which is dominated by Shi’ites. But this vengeance would not come through the capture of Baghdad, the spokesman vowed. It would come through the subjugation of Najaf and Karbala, cities that are home to some of the most sacred Shi’ite shrines. The Sunni fighters of ISIS would cheerfully kill and die, if necessary, to erase their blasphemous existence.

What army would rather raze a few shrines than seize a capital city? The answer says a lot about the disaster now unfolding in Iraq and rippling throughout the Middle East. The rapid march by ISIS from Syria into Iraq is only partly about the troubled land where the U.S. lost almost 4,500 lives and spent nearly $1 trillion in increasingly vain hopes of establishing a stable, friendly democracy. ISIS is but one front in a holy war that stretches from Pakistan across the Middle East and into northern Africa. A few days before ISIS captured the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, Pakistani militants driven by similar Sunni radicalism killed 36 in an assault on their country’s busiest airport. Holy war inspires the al-Shabab radicals who took credit for massacring at least 48 Kenyans in a coastal town on June 15 and explains why suspected al-Qaeda fighters in Yemen riddled a bus full of military-hospital staff the same day. It’s the reason Boko Haram has kidnapped hundreds of Nigerian schoolgirls and why Taliban fighters sliced off the ink-stained fingers of elderly voters who had cast ballots in Afghanistan’s June 14 presidential election. Osama bin Laden is dead, but his fundamentalist ideology–and its cold logic of murder in God’s name–arguably has broader reach than ever.

For now, the ISIS front is the most dangerous. The chilling prospect of holy warriors with dueling nuclear capabilities–Sunnis in Islamabad and Shi’ites in Tehran–remains a worst-case scenario, but the breakup of Iraq as a nation-state appears to be all but an accomplished fact. Two and a half years after the U.S. withdrew its last combat forces and more than a decade since the beginning of America’s war in Iraq, ancient hatreds are grinding the country to bits. Washington has reacted with shock–no one saw it coming–and the usual finger pointing, but today’s Washington is a place where history is measured in hourly news cycles and 140-character riffs. What’s happening in Iraq is the work of centuries, the latest chapter in the story of a religious schism between Sunni and Shi’ite that was already old news a thousand years ago.

The Sunni radicals’ dream of establishing an Islamic caliphate–modeled on the first reign of the Prophet Mohammed in the 7th century–has no place for Shi’ites. That’s why Iraq’s leading Shi’ite cleric responded to ISIS’s advance by summoning men of his faith to battle. So begins another Iraqi civil war, this one wretchedly entangled with the sectarian conflict that has already claimed more than 160,000 lives in Syria. Poised to join the fighting is Iran, whose nearly eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s cost more than a million lives.

To Americans weary of the Middle East, the urge is strong to close our eyes and, as Sarah Palin once put it so coarsely, “let Allah sort it out.” President Obama has kept a wary distance from Syria’s civil war and the turmoil of postwar Iraq. But now that the two have become one rapidly metastasizing cancer, that may no longer be possible. As long as the global economy still runs on Middle Eastern oil, Sunni radicals plot terrorist attacks against the West and Iran’s leaders pursue nuclear technology, the U.S. cannot turn its back.

“There is always the danger of passing the buck,” says Vali Nasr, a former Obama State Department official and an expert on Islam. “Not to say the region doesn’t have problems or bad leadership. It does. But these things won’t go away. They are going to bite us at some point.” What Leon Trotsky supposedly said about war is also true of this war-torn region: Americans may not be interested in the Middle East. But the Middle East is interested in us.

ANCIENT ENMITY

As he helped draw the post–World War I map of the Middle East, Winston Churchill asked an aide about the “religious character” of an Arab tribal leader he intended to place in charge of Britain’s client state in Iraq. “Is he a Sunni with Shaih sympathies or a Shaih with Sunni sympathies?” Churchill wrote, in now antiquated spelling. “I always get mixed up between these two.”

The Westerners who have sought to control the Middle East for more than a century have always struggled to understand the religion that defines the region. But how could the secular West hope to understand cultures in which religion is government, scripture is law and the past defines the future? Islam has been divided between Sunni and Shi’ite since the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 and a bitter dispute that followed over who should lead Islam. (Sunnis called for an elected caliph. Shi’ites followed Muhammad’s descendants.) Over the centuries, the two sects have developed distinct cultural, geographic and political identities that go well beyond the theological origins of that schism. Today, Sunnis make up about 90% of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims. But Shi’ites have disproportionate power, with their control of Iran and their concentration around oil-rich areas.

The seat of Shi’ite power is Iran, whose 1979 Islamic revolution cracked open the bottle in which the region’s sectarian tensions had been sealed for many years–first by the nearly 500-year rule of the Ottoman Empire and then by Western colonizers. Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini’s overthrow of the pro-American Shah of Iran fired the ambitions of jihadists elsewhere and instituted the region’s first modern theocratic regime. The ensuing American hostage crisis established Iran’s new leadership as a mortal enemy of the West. In 1983, when the Shi’ite militant group Hizballah bombed a U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, killing 241 Americans, and began kidnapping Westerners in the region, Islamic terrorism seemed to wear a Shi’ite face. Iran’s long war with Sunni-dominated Iraq–sparked in part by Khomeini’s call for a Shi’ite uprising in Iraq–put the U.S. on the side of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

Indeed, America’s leaders were so blithe about Sunni radicalism that the CIA eagerly supported the training and arming of young jihadists–among them a rich young Saudi named Osama bin Laden–to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. That victory was short-lived as bin Laden and other Sunni warriors, lit by the conviction that Allah had empowered them, founded al-Qaeda and declared the goal of establishing a new caliphate. Targeting the U.S. and other Western powers, which bin Laden called “the far enemy,” was just a step toward the nearer yet ultimate aim: to drive the U.S. and its allies out of the region, ending their support for repressive infidel rulers in places like Egypt, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

The national boundaries plotted on Western maps have little place in the radical vision of the restored caliphate. The ambition is absolute Sunni authority and Shari’a–Islamic law–over the entire Muslim world. To achieve this, the West need only be banished, while the Shi’ites must be eradicated. “There are all kinds of al-Qaeda documents in which its operatives say things along the lines of ‘the Americans are evil, the secular tyrants are evil, the Israelis are evil–and the Shi’ites are worse than all of them,’ ” says Daniel Benjamin, the former counterterrorism coordinator at the State Department who is now at Dartmouth College. Some Saudi textbooks depict Shi’ism as more deviant than Christianity or even Judaism. A common bit of folklore among Lebanese Sunnis, Nasr writes in his book The Shia Revival, is that Shi’ites have tails.

For decades, the dictators of the Middle East have warned their democratic patrons in the West that only their repressive measures could stifle the Shi’ite-Sunni rivalry. But in the aftermath of 9/11, U.S. leaders concluded that repression was part of the problem. Touting a new “freedom agenda,” President George W. Bush pressed for an invasion of Iraq to topple Saddam and–this was the expressed goal, anyway–establish democracy in his place. Instead, Bush let loose the sectarian furies. The eventual replacement of Saddam with the pro-Iranian Shi’ite ruler al-Maliki, who assumed power in 2006, set off alarms across the Sunni world, especially in oil-rich monarchies of the Persian Gulf like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Shi’ite Iran’s march toward a nuclear weapon turned alarm into existential panic.

With the 2011 Arab Spring, many in the West grew hopeful that the spirit of democracy was finally taking root. Instead, as in Iraq, the toppling of dictators unleashed the religious radicals almost everywhere. In Syria, strongman Bashar Assad’s struggle to survive has evolved into a cauldron of Sunni-Shi’ite bloodletting. Sunni warriors from across the world have gathered to fight the forces of Assad, a member of the Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shi’ism and a close ally of Iran, which has poured men and money into the fight. “All the jihadists in the world are coming to Syria. It’s the new Afghanistan,” says one Arab diplomat. A June report by the New York–based Soufan Group estimates that more than 12,000 foreign fighters have traveled to Syria to join the fray.

As the fight against Assad, now in its fourth year, grinds on, the Sunni goal of forcing him from power endures. But the older goal of breaking down borders to establish the new caliphate has come to dominate the conflict, and the killing has bled easily from Syria into Iraq. “No one’s talking about fighting Bashar anymore,” says the diplomat.

THE REIGN OF ISIS

The Islamic state of Iraq and greater Syria is at once highly modern and wholly medieval. Its fighters eagerly post propaganda videos on YouTube and photos of executed prisoners on Facebook. Credit ISIS with one of the most demented mashups of our time: a tweeted crucifixion. Ruling by a radical interpretation of Shari’a–with its puritanical mores and bloody punishments–ISIS now controls a swath of land that stretches from eastern Syria to central Iraq. Not since the Taliban ruled Afghanistan have men with a literal interpretation of Islamic texts and the determination to kill Westerners occupied so much territory.

And they are more fearsome than the militants who came before them. When what became ISIS first gathered in Iraq to attack Americans after the U.S. invasion, they called themselves al-Qaeda in Iraq. But their violence against fellow Muslims appalled the senior al-Qaeda leadership. Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden’s most senior comrade, chastised the group for killing Shi’ites too wantonly. (Al-Zawahiri remains wary of ISIS and has dueled with the group’s charismatic leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, for primacy in the global jihad movement.) Eventually, American troops forged or bought alliances with moderate Iraqi Sunnis repelled by endless beheadings and joyless social restrictions. The 2007 U.S. troop surge and the Sunni awakening had decimated the group by the time George W. Bush left office.

Two factors gave ISIS new life. One was Syria’s civil war. Largely funded by wealthy Gulf Arabs and driven by suicidal fanaticism, the fighters of ISIS moved across the porous border with viciousness unmatched even by al-Nusra Front, a rival Sunni extremist faction whose soldiers ultimately report to al-Qaeda’s Pakistan-based leadership. The group’s rampage through Iraq included a boast of executing 1,700 captured Iraqi soldiers–a slaughter conveniently documented online for propaganda purposes. (“This is the destiny of al-Maliki’s Shi’ites,” read one caption online.)

The second factor was the Iraqi Prime Minister. Insecure in his power and shrugging off demands from Washington to be more inclusive, al-Maliki has trampled the Sunnis who once ruled Iraq. Sunnis have been forced out of government and military posts, and al-Maliki’s security forces have attacked peaceful Sunni protests. Many Sunnis now see al-Maliki as nothing more than a Shi’ite version of Saddam.

This may explain how as few as 1,000 ISIS fighters, originally equipped with small arms and pickup trucks, managed to overrun some 30,000 Iraqi troops to capture Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul, before they and their allies took Kirkuk, Tikrit and Tal Afar. They were, if you will, welcomed as liberators. Indeed, many Sunnis in the Iraqi army literally stripped off their uniforms rather than fight for al-Maliki. “ISIS is the spearhead in a Sunni coalition,” says Kenneth Pollack, a former CIA analyst and Iraq expert now at the Brookings Institution. That coalition now features everyone from disgruntled tribal leaders to former Saddam loyalists. “What happened is a rebellion,” a 49-year-old Mosul man tells TIME, asking that his name be withheld for his safety. “People here have been feeling frustrated with the government for a long time.”

U.S. officials grasping at strands of hope are clinging to the idea that ISIS will be stopped short of Baghdad and the Shi’ite holy cities, blocked by a hostile Shi’ite population. But even the hopeful view is bleak: “If that’s what you’re dealing with, I think we’re headed for a grinding guerrilla war that’ll last a long time, with extremely high death rates, that could end up sucking in more of the neighbors,” says Stephen Biddle of the Council on Foreign Relations, who has advised the Pentagon on Iraq.

That would suit ISIS just fine. A climactic war with the Shi’ites is exactly what the group wants. And as its territory grows, so does ISIS’s readiness for such a war. As they conquered major Iraqi cities, ISIS fighters looted military bases for guns, ammunition and U.S.-made Humvees–along with at least two helicopters. They have also plundered gold and vast sums of cash from banks. One unconfirmed estimate by local officials pegged the haul at a staggering $425 million.

Even if that figure is inflated, ISIS–estimated at about 10,000 men strong in Iraq and Syria combined–has begun collecting taxes, levying fines and running lucrative mafia-like operations in its zone of control, giving it the resources to administer a quasi-state. The group already pumps oil and even sells electricity to the very Assad government it is warring to overthrow. “As long as the support of these Sunni elements holds, ISIS looks well positioned right now to keep the territory it has captured, absent a major counteroffensive,” says one U.S. official. Fear of alienating moderate Sunnis may explain why ISIS hasn’t imposed severe Shari’a law in most of its newly captured Iraqi population centers.

If ISIS’s gains prove durable, the de facto Sunnistan they have created will pose a severe threat to the U.S. and its Western allies. According to intelligence officials, thousands of European passport holders have joined the fight in Syria, and no doubt a number of them are now in Iraq. Their next stop could be anywhere. U.S. officials say Moner Mohammad Abusalha, an American from Florida, recently triggered a suicide truck bomb in Syria after posting a jihadist recruiting video online–in English. A French Islamist who killed three people at the Jewish Museum in Brussels on May 24 is believed to be a veteran of ISIS in Syria. Attacks on the far enemy may not be the endgame for ISIS, but they could bring stature and propaganda benefits. On June 15, the group’s leader, al-Baghdadi, issued a message for the U.S.: “Soon we will face you, and we are waiting for this day.”

BOUNDARIES OF SAND

As haunting as the threat of a terrorist haven may be, the significance of the ISIS victories goes far beyond the threat it poses to Baghdad or the West. With lightning speed, ISIS has begun to erase the Middle East map drawn by Europeans a century ago. In 1916, Mark Sykes, a young British politician, and François Georges-Picot, France’s former counsel in Beirut, agreed to divide the region to suit Western goals. With an eye to the death of the Ottoman Empire–on the losing side of WW I–the two diplomats slashed a diagonal line across a map of the region, from the southwest to the northeast, and divided the empire between their countries. “What do you mean to give them, exactly?” British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour asked Sykes during a meeting at 10 Downing Street, according to James Barr’s 2012 book, A Line in the Sand. “I should like to draw a line,” Sykes said, as he ran his finger along the map of the Middle East, “from the ‘e’ in Acre to the last ‘k’ in Kirkuk.”

After crossing the line between Syria and Iraq, ISIS fighters took a bulldozer to the berm that marked that border.

Once shattered, the pieces may never be reassembled. Al-Maliki shows no sign of the tremendous political skills needed to earn the cooperation of spurned Sunnis. Iraq’s Shi’ites, with their reservoirs of oil in the south, may be content to slough off the comparatively barren Sunni lands to the north and west. The country’s long-beleaguered Kurds, meanwhile, may seize this moment to finally claim their independence. When ISIS soldiers drove al-Maliki’s forces from the oil-production center of Kirkuk, the formidable Kurdish militia known as the peshmerga stepped in to grab the city. Neighboring Turkey has lately begun to reconsider its long-held opposition to a Kurdish state. Perhaps an oil-rich, peaceful buffer between the Turks and the anarchy of Iraq wouldn’t be so bad. “We’ve said all along that we won’t break away from Iraq but Iraq may break away from us,” Qubad Talabani, Deputy Prime Minister of the Kurdish Regional Government, tells TIME. “And it seems that it is.”

Other borders could also be in danger. Western Iraq abuts the kingdom of Jordan, a vital U.S. ally and oasis of regional moderation. Though he is a Sunni, Jordan’s Western-educated King Abdullah is precisely the sort of ruler ISIS would hope to topple, and Abdullah’s kingdom sits inside the sprawling caliphate sometimes depicted on ISIS maps. So does Lebanon, a sectarian tinderbox. Syria, meanwhile, may be melting into unofficial quasi-states.

The region’s heavyweights, Sunni King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia and Shi’ite Ayatullah Ali Khamenei of Iran, watch with wariness and few good options. For Abdullah, al-Maliki’s pain is a welcome development, for the Saudis have always felt threatened by his ties with Iran. On the other hand, since the earliest days of al-Qaeda, the Sunni radicals have cherished the dream of deposing Abdullah’s family and taking possession of the Arabian holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The Saudis look to Iraq and see nothing but enemies. The same goes for Israel, ever a prime target for both Sunni and Shi’ite militants.

In Iran, the growing momentum of Sunni radicalism has set alarms clanging. As the movement obliterates borders, the sheer number of Sunnis–nine of them for every Shi’ite–compels Iran to act. The pressure is such that Tehran is contemplating one of the strangest partnerships in its 35-year revolutionary history, wading into tentative talks on the crisis with the Great Satan himself: Uncle Sam.

THE FOREVER WAR

Barack Obama first ran for President, in large measure, to end the Iraq War, and he takes pride in having done so. It surely wasn’t easy, then, to announce that some 170 combat-ready soldiers were headed to Baghdad to secure the U.S. embassy. The White House insists that Obama won’t re-enter a ground war, though military planners are exploring possible air strikes. (For now, limited intelligence and ill-defined targets have put bombing on hold.) The likelier option is a small contingent of special forces to advise Iraq’s military. But Obama wants to leverage any possible U.S. help to force al-Maliki into major political reforms. A new governing coalition giving Sunnis real power could offer the country’s only hope for long-term survival. Whether something the U.S. couldn’t accomplish when its troops were still in Iraq is feasible now is another question.

Clearly, Obama was mistaken in declaring, after the last U.S. troops departed in 2011, that “we’re leaving behind a sovereign, stable and self-reliant Iraq.” But while Washington plunged into the blame game, fair-minded observers could see that the U.S.’s road through the region is littered with what-ifs and miscalculations. What if we had never invaded Iraq? What if we had stayed longer? What if Obama had acted early in the Syrian civil war to put arms in the hands of nonradical rebels? “We would have less of an extremism problem in Syria now, had there been more assistance provided to the moderate forces,” Obama’s former ambassador to Damascus, Robert Ford, told CNN on June 3.

Yet on a deeper level, the blame belongs to history itself. At this ancient crossroads of the human drama, the U.S.’s failure echoes earlier failures by the European powers, by the Ottoman pashas, by the Crusaders, by Alexander the Great. The civil war of Muslim against Muslim, brother against brother, plays out in the same region that gave us Cain vs. Abel. George W. Bush spoke of the spirit of liberty, and Obama often invokes the spirit of cooperation. Both speak to something powerful in the modern heart. But neither man–nor America itself–fully appreciated until now the continuing reign of much older spirits: hatred, greed and tribalism. Those spirits are loosed again, and the whole world will pay a price.

–Reported by Aryn Baker and Hania Mourtada/Beirut, Massimo Calabresi, Jay Newton-Small and Mark Thompson/Washington and Karl Vick/Jerusalem