While growth in the economy slows, Xi Jinping follows in Mao’s footsteps—and some members of the Communist Party aren’t happy

Millions of commemorative plates bear his portrait, a Mona Lisa smile leavened by the benign air of Winnie the Pooh. Poets lavish ornate verse on him–“My eyes are giving birth to this poem/My fingers are burning on my cell phone,” wrote one amateur bard in February, describing his search for the perfect paean. Bookstores across China give prime display to his collection of speeches and essays, which has sold more than 5 million copies, according to state media. His ideology is even enshrined in an animated rap video, with one line that goes: “It’s everyone’s dream to build a moderately prosperous society. Comprehensively.” A killer rhyme it is not, but who cares when you’re almost certainly the most powerful ruler on the planet?

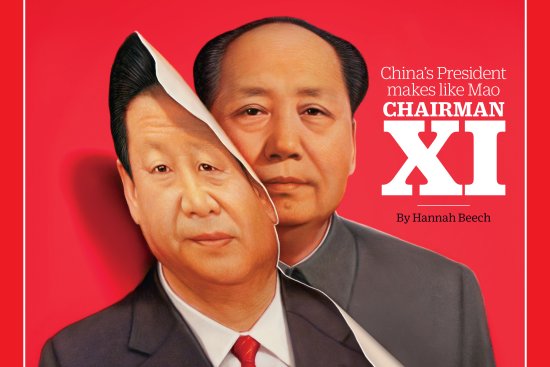

Little more than three years into his decade-long tenure, Chinese President Xi Jinping has already accumulated more authority than any of his predecessors since Mao Zedong, the founder of the communist People’s Republic of China. Xi has taken personal control of policymaking on everything from the economy, national security and foreign affairs to the Internet, the environment and maritime disputes. Now the 62-year-old scion of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) royalty stands at the center of a personality cult not seen in the People’s Republic since the days when frenzied Red Guards cheered Chairman Mao’s launch of the Cultural Revolution. “Xi is directing a building-god campaign, and he is the god,” says Zhang Lifan, one of a shrinking circle of Beijing scholars who dare to question China’s leader.

Five decades after the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was launched in 1966–sparking a political cataclysm that upended hundreds of millions of lives–Xi is using some of Mao’s strategies to unite the masses and burnish his personal rule, injecting Marxist and Maoist ideology back into Chinese life. Hundreds of thousands of cadres have been forced to attend ideological education classes, while Xi’s government rails against “hostile foreign forces” it believes are intent on weakening a resurgent China. “Like Mao, Xi thinks if China succumbs to Western values, these forces will destroy not only China’s exceptionalism but also the stability of the Chinese Communist Party,” says Roderick MacFarquhar, a Harvard expert on Chinese politics.

Xi’s personality cult is discomfiting some party skeptics, who credit China’s economic success to the collective, depersonalized leadership style that prevailed after the end of the Mao era. In March, an online article in a newspaper affiliated with the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, which roots out official corruption, appeared to disparage Xi’s accumulation of power and his notoriously tight band of advisers. An open letter calling for Xi’s resignation, attributed to “loyal Communist Party members,” briefly circulated on the Internet. Who exactly wrote the letter, which originally appeared on a government-linked news portal before being expunged, isn’t clear. But its timing–as China’s annual political meeting took place–was a reminder that there is deepening skepticism inside the party about Xi’s direction.

Beijing’s harsh response was telling as well. In recent days, Chinese authorities have detained more than 20 people, including family members of exiled writers who deny having anything to do with the letter’s publication, in an attempt to root out the mystery authors. The State Council Information Office, which publicizes the position of China’s Cabinet, went to Twitter to dismiss speculation about the letter: “Such gossips are meaningless.”

The detentions, along with a raft of new rules limiting free expression, are part of Xi’s mounting crackdown on human rights, which has dashed hopes for any political liberalization in China. But Xi’s real challenge may well be the lingering memory of the damage done by the Cultural Revolution’s veneration of a single leader. “Xi’s campaign for a personality cult is doomed,” says Feng Chongyi, a history professor at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia. “Because of the Cultural Revolution, Xi’s peers are vigilant against a leader holding arbitrary power over their life and property.”

Ever since Deng Xiaoping launched economic reforms in the late 1970s to restore sanity after the Cultural Revolution, the CCP has tied its legitimacy not to ideology but to improving Chinese livelihoods. Hundreds of millions of people were lifted out of poverty, and by one estimation the officially communist nation now claims the world’s largest middle class. But China’s growth has slowed–last year Beijing failed to reach its own 7% growth target, and this year’s projection of 6.5% to 7% may be met only through fudged numbers. The CCP is in danger of losing the mandate of heaven that comes with propulsive economic growth.

Yet rather than accelerating market reforms, Xi appears more preoccupied with politics than economics. He has retreated into the world of Mao: personality cults, plaudits to the state sector and diatribes against foreigners supposedly intent on destroying China. “The revival of Marxism and the closing of the door on the West is so irrelevant to China now,” says Harvard’s MacFarquhar. “But the Communist Party has got nothing else. You could say it’s a desperate last stand.”

This national reckoning comes just as China seems to get more powerful by the day, its influence shaping elections in Africa and consumption patterns in Europe. Eager to advance China’s destiny as a global superpower, Xi has pushed territorial claims in the South China Sea, blaming regional tensions on the U.S. Last September he held a massive military parade to show off China’s growing arsenal–and his own dominance over the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). In 2015, China’s President globe-trotted to 14 countries and was feted in each, even enjoying a golden-carriage ride in Britain.

Xi’s forcefulness at home and stature abroad resonate among many Chinese, who believe someone like him is needed to propel the country to pre-eminence on the world stage. “He is a powerful leader, like Chairman Mao,” says Wang Cheng, who each month sells around 180 plates decorated with the President’s face. Says Zhong Feiteng, a professor at the Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies at the government-funded Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: “Xi Jinping’s vision for China is very confident, very engaged with the world. He is also personally a very confident man.”

Qiao Mu sees it differently. “Xi Jinping is like an emperor who rose from red nobility,” says Qiao, who headed the international-communications department at Beijing Foreign Studies University before his outspokenness got him relegated to a job in the college library. “People dare not criticize him. But Xi is not a god. He cannot know everything. He cannot do everything.”

The morning of Feb. 19 was a busy one for Xi. In a few hours, trailed by dozens of underlings dressed identically to their leader, he visited the headquarters of the nation’s biggest newspaper, TV network and news agency. His mission: to ensure “absolute loyalty” from the assembled media, whose work, he reminded them, was above all to “reflect the party’s will and views, protect the authority of the central party leadership and preserve the party’s unity.”

In China, the party’s mannerisms can often feel exaggerated. For example, the party’s mouthpiece is a newspaper called the People’s Daily, though these days it seems more inclined to advance the interests of Xi himself. He was mentioned in the front section of the People’s Daily more than twice as much as his predecessors Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, according to 2014 research by Qian Gang of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong. Last December, Xi’s name appeared in 11 front-page headlines.

Xi has demanded party devotion from more than just the state-owned media. He has lectured artists that “art and culture will emit the greatest positive energy when the Marxist view of art and culture is firmly established.” Soldiers in the PLA have been reminded that they fight not for China but for the nation’s ruling communists. In March, during the annual meeting of China’s rubber-stamp parliament, state media exhorted the party’s 88 million members to study the wisdom of Xi’s “important thoughts.” On university campuses, the polluting influence of foreign textbooks has been officially discouraged, even if Karl Marx was born in Germany. “Western nations must realize that the Chinese Communist Party very much believes that it is in an ideological war with the West, and the United States in particular,” says David Shambaugh of George Washington University, whose latest book is called China’s Future.

Marxist maxims and Maoist slogans are at odds with modern Chinese life, so different from the isolated and chaotic years of the Cultural Revolution. How can a Beijing kid, raised on Starbucks and The Big Bang Theory, understand calls to reject the West and embrace socialist heroes? And for the party elite, the heroic elevation of Xi can bring back uncomfortable memories of Mao’s excesses.

Already, a tentative pushback has begun. After Xi’s February media tour, Ren Zhiqiang, a retired real estate mogul and party member who had more than 37 million followers on China’s version of Twitter, questioned the President’s demand for loyalty. Ren’s account was promptly shuttered, and local party officials said he “constantly published illegal information and wrong remarks that generated vile influence, seriously damaging the party’s image.” The CCP’s vitriol against a former soldier with impeccable political connections shocked many. “It was a 10-day Cultural Revolution,” says Chinese historian Zhang. But since then Ren has not been disciplined further.

Others have spoken up, including employees of state-linked media who, at the threat of dismissal and detention, have publicly assailed Xi’s crackdown on freethinkers and his campaign for party loyalty. These seedlings of dissent, though, do not a putsch make. Besides his projection of strength, Xi is genuinely popular among many Chinese because of his anticorruption campaign, which has resulted in the arrest of tens of thousands of wayward officials. “Elites across the system–businesspeople, intellectuals, military officers, party apparatchiks, government bureaucrats at all levels–are all keeping their heads down under the current political conditions in China,” says Shambaugh.

But if most ordinary Chinese still support Xi, their ruler should know that awakening revolutionary fervor can backfire. The city of Pingxiang in southern China is famous in communist lore as the place where a young Mao helped organize a strike in 1922 at a coal mine in the Anyuan district. A propaganda poster was commissioned during the Cultural Revolution to mark the moment: Mao strides forward with socialist purpose to save the downtrodden masses. But of the eight state-owned mines in Pingxiang, only three are now operational, a result of the global coal glut. Hundreds of miners have become so frustrated by their low pay that they organized a rare demonstration in late February and early March.

Xiao Bin, a Pingxiang coal miner, has a poster of Mao at Anyuan decorating his spartan home. The 37-year-old still holds out hope that Xi might take care of the masses. After all, isn’t an iron rice bowl, the promise of state succor, at the heart of Marxism, the very same ideology China’s current President is reviving? But what happens if the labor protest, in which Xiao participated, doesn’t yield results? “Then we may go petition in Beijing, shouting ‘We must eat to survive’ in Tiananmen Square,” Xiao says. “It’s dangerous, but it’s just like Mao’s Anyuan strike, when the workers carried out revolution.” That’s a word that should worry even a man who can claim to be Mao’s heir.

–With reporting by YANG SIQI/BEIJING