On a late September afternoon, just before pitcher Kyle Hendricks will take the mound against the Pittsburgh Pirates, a handful of Chicago Cubs players and coaches are huddled around a table in the visitors’ locker room, all trying to help. That night, the Cubs will count on Hendricks to clinch the team’s 100th victory of the season and propel them into the playoffs as the hottest team in the game—and a trendy pick to win their first World Series since 1908. But first, the brain trust needs to map out the game plan.

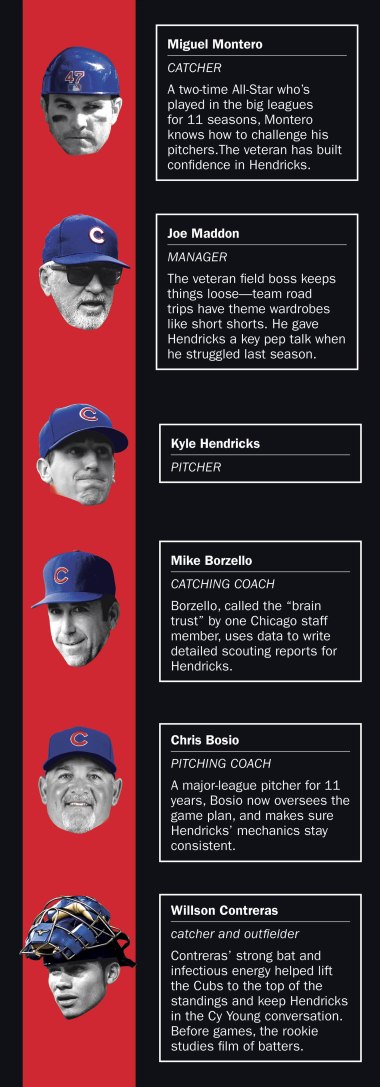

Seven laptops and two oversize monitors are laid out in front of them. Mike Borzello, the team’s catching instructor, chats with scout Tommy Hottovy, informally known as Chicago’s “run-prevention coordinator,” or the guy tasked with figuring out how to make the pitching and defense better. It’s Borzello’s job, working alongside pitching coach Chris Bosio, to prepare reports on each of the hitters Hendricks could face that night, outlining their tendencies during different phases of a given at-bat. Willson Contreras, who’ll be catching the game, pulls up video from a matchup earlier in the season of a Pirates player launching a home run off Hendricks. Soon he’ll meet with Borzello and Hendricks to go through the Pittsburgh lineup batter by batter, strategizing their approach to each. Presumably he won’t be calling that pitch.

All this preparation, and collaboration, pays off. Hendricks throws six shutout innings in a 12-2 Cubs victory. It’s another stellar outing for Hendricks, 26, who has defied convention all year. After beginning the season as the last starter in the Cubs rotation, the soft-throwing Dartmouth graduate whom teammates call the Professor has blossomed into one of the best pitchers in baseball. He finished the regular season with the lowest earned run average (ERA) in the majors—the first time a Cubs player has done so since 1938—cementing his transformation from afterthought to Cy Young Award candidate. Hendricks has continued to impress in the playoffs, helping the Cubs knock out the San Francisco Giants before dropping a pitcher’s duel to Clayton Kershaw of the Los Angeles Dodgers, 1-0, in Game 2 of the National League Championship Series.

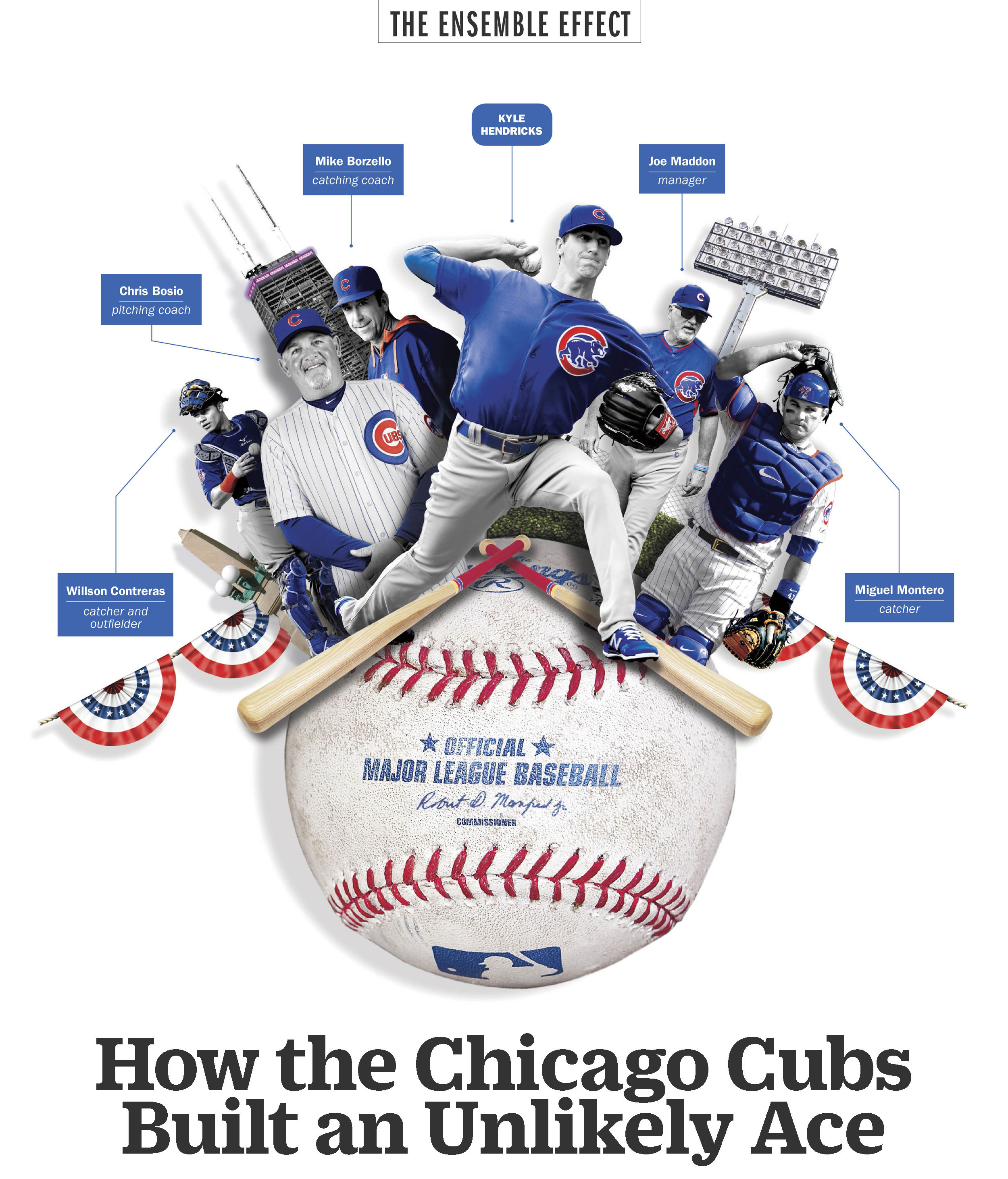

The Team behind Kyle Hendricks

Chicago’s defense has been stellar, and its lineup boasts two MVP candidates in third baseman Kris Bryant and first baseman Anthony Rizzo. But the team’s starting pitching has been its anchor. Jon Lester won 19 games this season and finished with the second lowest ERA in baseball. Jake Arrieta, the 2015 National League Cy Young winner, threw a no-hitter earlier this season. Yet even in this group, Hendricks stands out. A throwback in an era of power pitching, Hendricks succeeds with precision and guile, mixing his pitches—an elite changeup, a curveball, a sinker and a fastball that typically tops out at just 90 m.p.h.—to keep batters guessing.

Since Hendricks can’t overpower hitters, he needs to outsmart them. And that’s where the locker-room commando squad comes in. Only a dedicated team of behind-the-scenes tinkerers, working with a willing student like Hendricks, could engineer the unlikeliest story of this baseball season and maybe, just maybe, bring a world championship to Chicago’s North Side for the first time since Teddy Roosevelt was President. “It’s pretty special,” says Hendricks. “It’s a testament to a lot of the help I’ve received, honestly.”

Hendricks grew up in San Juan Capistrano, Calif., the son of a golf pro (dad John) and a medical-management consultant (mom Ann Marie). After three years in the Ivy League and three more in the minors, Hendricks reached the big leagues with the Cubs in 2014. He finished his rookie season with an impressive 2.46 ERA. Last year, however, his ERA ballooned to 5.15 after seven starts. To Cubs manager Joe Maddon, the problem wasn’t talent. “You could see in his face, he was lacking self-confidence a little bit,” says Maddon, a veteran skipper known for keeping his teams loose. “And he needs his confidence to be able to execute his pitches.”

The ego of a major-league pitcher is a delicate thing. The position demands someone with the confidence to stand alone, on a mound in the middle of a stadium filled with tens of thousands of fans, and stare down the best hitters in the world—and the ability to do it all over again after one of those hitters blasts his pitch over the outfield wall.

Maddon is a master of unconventional motivation. This season he set up a strobe-light-equipped party room in Wrigley Field so the Cubs could celebrate home wins and wore a T-shirt reading try not to suck-tober to let off some of the pressure on his heavily favored charges. But he sensed that Hendricks needed something more basic. “He kept telling me. ‘Hey, just be you,’” Hendricks says of their pep talks. “ʻDo your thing.’ He never wavered.” Neither did Hendricks, who finished 2015 with a respectable 3.95 ERA.

The skipper’s faith wasn’t the only thing that sparked his turnaround. No pitcher can succeed without a catcher calling the right game, and Hendricks also credits his battery mates for his emergence. “It’s very hard to go back and retrieve all the information and make in-game adjustments on your own,” he says. “That’s where the catchers come in.”

Contreras, who was called up from the minors in June, and Miguel Montero, an 11-year veteran, have caught all but four of Hendricks’ starts this year. Contreras is the young spark plug, while Montero plays the sage, pulling Hendricks aside for one-on-one tactical sessions. “We have to manage so many different personalities,” Montero says of the catcher’s unofficial role as dugout shrink. “We have to know how to talk to each different guy. Because they’re not all the same.”

Back in Pittsburgh, two weeks before the Cubs would go on to win the National League Division Series, Hendricks is facing his tightest spot of the game: bottom of the sixth inning, bases loaded, two outs. If Hendricks can preserve the shutout, it would push his ERA below 2.00 and keep him squarely in the Cy Young mix.

Bosio, Chicago’s pitching coach, approaches the mound. The scouting report says to open with a “hip shot”—a ball that starts in on left-handed hitters before breaking back toward the plate. Toss the game plan, Bosio tells Hendricks. The hitter’s probably expecting the inside pitch. Hendricks follows Bosio’s advice and gets the batter to line out to left field, ending the inning and keeping the shutout intact.

Good pitching coaches can make a career. Part boss, part mentor, part psychologist, they’re the ones tasked with keeping all those delicate egos from crumbling. Their value has been clear since the early 20th century, when “Uncle” Wilbert Robinson, a former Baltimore Orioles catcher, helped revive the career of disappointing New York Giants hurler Rube Marquard, according to The Pitcher, co-written by official MLB historian John Thorn.

PLUS: Meet the team behind Luke Cage

Known as “the $11,000 lemon,” Marquard languished in 1909 and 1910; after working with Robinson, he became a Hall of Famer. In the 1950s, as pitching staffs added more relievers, teams started hiring specialized coaches to work solely with pitchers. “The best coaches aren’t going to listen to your bullsh-t,” says Ron Darling, a TBS analyst and former big-league pitcher who played for two of the all-time best, Mel Stottlemyre and Dave Duncan.

Bosio, a big-league pitcher for 11 years, may well have saved Hendricks. At the start of last season, as Hendricks labored through a series of bad outings, Bosio noticed that he was dragging his arm too far behind his body during his delivery. So he and Hendricks set out to repair the problem, relearning the correct motion. “It’s not that easy once you start having bad habits to just fix it and get right back to your mode,” says Hendricks. “It took a lot of work between Bos and I coming out early, working on drills and getting me back in line.”

Before every series, Bosio holds a meeting with the entire pitching staff to review the hitters’ tendencies. Before each game, Borzello, the starting catcher and the starting pitcher powwow to brush up on the scouting report. “This is something we’ve started to do in the last couple of years, because the information can be lost,” says Bosio. Even between innings, the pitcher and catcher will consult with Bosio or Borzello to drill the data home.

Helpful information, sure. But data is only as good as a player’s ability to utilize it. And few have done that better than Hendricks. “Kyle’s the perfect example of a guy who’s taken the information to another level,” says Bosio. “It’s a pleasure coming out and seeing that little smirky, professor-like smile on his face. I know he’s always thinking about his game.”

All that’s left for Hendricks and the rest of the Cubs organization is banishing that billy-goat curse once and for all. “We as a group have had some really tough times,” says Bosio, whose pitching lost nearly 100 games just three seasons ago. “Right now, it’s the best time of our lives. And to a man, we’re not done. And Kyle’s leading the charge.”

Oct. 20, 2016