Magic comes in many vials. Golfer Jordan Spieth opened a highly potent bottle last year. At a mere 21, he won the Masters and the U.S. Open championships back-to-back, then added top-four finishes in the remaining major tournaments. An epic season at any age, but glittering with the thrill of something new.

Prize money in the millions, and endorsement money in the tens of millions, rained down on the slim and winsome Texan as golf fans fell under his spell.

Another elixir from the wizard’s cabinet has been unstoppered by Jason Day, the No. 1–ranked golfer in the world. The strapping Australian wasn’t a phenom; he trudged, rather than vaulted, to the top. But now his life and career are magically synchronized; in his late 20s, he has grown into himself, with a wife and two young children to balance out his stunning PGA Championship last August, when he became the first player in major-tournament history to beat par by 20 strokes.

And then there is a magic known only to Jack Nicklaus.

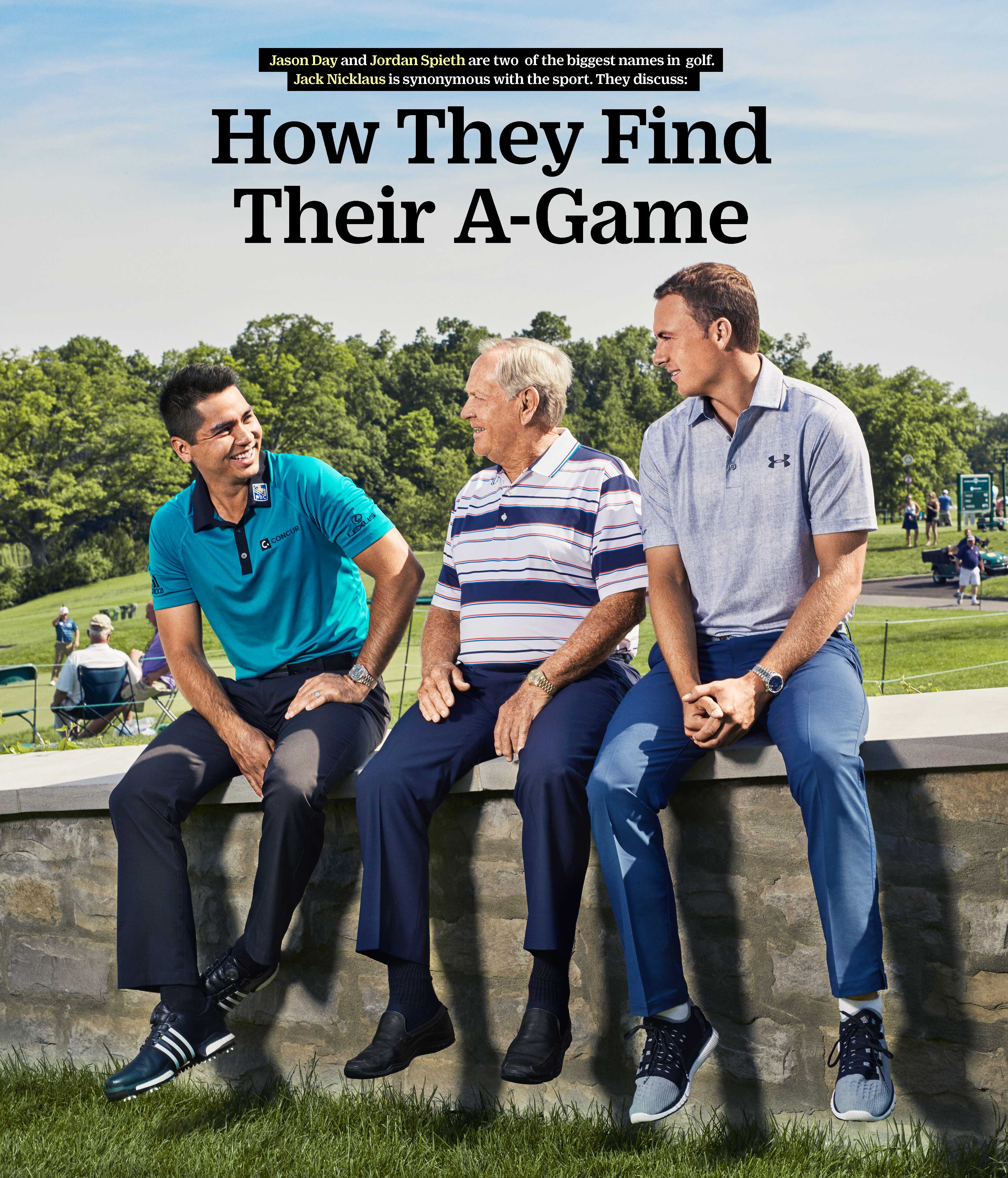

You can see it on the faces of Spieth and Day as they sit down to join Nicklaus for a conversation with TIME on a patio overlooking Muirfield Village Golf Club, a Nicklaus-built preserve in Dublin, Ohio. Down below, the journeymen of the PGA Tour are practicing for the annual Memorial Tournament, but up here two of the best in the world are hanging on the old man’s every word. They call him “Mr. Nicklaus.”

He was the prodigy once, like Spieth: a laser-eyed 22-year-old capable of grinding down the great Arnold Palmer to win the 1962 U.S. Open in his first year as a pro. And like Day, he was a man in full flood, winner of seven major titles from ages 30 to 35, while Barbara mothered their five stair-step children and he laid the foundations of a business empire.

But the magic they have captured at this moment Nicklaus somehow harnessed for a lifetime. Now 76—with even the stunning career of Tiger Woods not quite measuring up to his own—Nicklaus not only reached the top: he magically stopped time, or at least slowed it down to a crawl. When even the best golfers typically number their time as major champions in years, his reign spanned decades. Nearly a quarter-century, actually, from the ’62 Open to the 1986 Masters. Through slumps and injuries, competing against such giants as Palmer, Player, Watson, Trevino and Ballesteros, he holds the records for the most major victories (18), the most second-place finishes (19) and the most top 10s (73).

No one else comes close.

Where did he find that particular potion?

“I don’t think you have competition with anybody else,” says the man long ago branded the Golden Bear. More silver now than gold, but still with a champion’s formidable forearms and fingers curling unconsciously into a grip. No matter who else was on the course, the Bear hunted alone. “My philosophy was always basically you are playing one shot at a time, and you play one day at a time, and you play one year at a time, and you are always trying to climb a mountain.”

Nicklaus continues: “I don’t think Jason has a competition with Jordan or vice versa. There is only one person you can control out there, and that is yourself. And whether he makes a 30-footer,” Nicklaus gestures toward Spieth, “he certainly doesn’t have any control over it,” gesturing now at Day. And back at Spieth: “He makes a lot of them, you know.”

Says Day: “A little too many.”

“I don’t know about too many. I hope you guys keep making a whole bunch of them,” the Bear resumes. “I think that’s great for golf. But you know, you control yourself. You control your own physical well-being. You control your own golf game. You control your own competitive instincts. Everybody asks, ‘Who was your toughest competitor?’ And I said, ‘Me.’”

And what a fierce one he was. There are a million examples—this is one:

Leading the 1972 U.S. Open by a comfortable three shots with two holes to play, Nicklaus stood on the 17th tee at Pebble Beach with a gale blowing from the Pacific into his face. A long par-3 surrounded by cliffs and sand, the hole cried out for a safe shot. But Nicklaus pulled the most notoriously difficult club from his bag and dared himself to hit the shot of a lifetime.

“Even God can’t hit a 1-iron,” golf legend Lee Trevino famously quipped of the tiny blade with the pea-size sweet spot. That’s the difference between God and Jack Nicklaus.

The ball split the wind like a bullet, landed lightly as a ballerina, and hit the reed-thin flagstick. His birdie putt was a tap-in.

But to prove his point about things in and things beyond one’s own control, that very same hole, 10 years later, was the site of another miracle birdie: Tom Watson’s chip-in from off the green to beat Nicklaus for the 1982 U.S. Open title.

“I always felt like I was trying to keep getting better,” the Bear resumes. “I had goals in front of me, even when I was in my 40s—I won the Masters at 46—just kept trying to work myself to get better. And all of a sudden 25 years or so have passed.”

On this warm spring morning in central Ohio, Spieth was looking ahead to his 23rd birthday, which falls on July 27. No one so young could possibly understand how 25 years can pass “all of a sudden.” It is a thing that older people say, first with astonishment, later with resignation. One of the distinctions the three men have in common is their status as “ambassadors” for Rolex, and when they compare the watches on their wrists, they discover that Nicklaus wears a timepiece that is twice as old as Spieth. Life begins so slowly, like a thrill ride climbing to the release point, then passes in a whoosh.

So Spieth has a touch of awe in his voice when he tackles the idea of competing so brilliantly for so long. The concept is both abstract and compelling, like a mountaintop viewed from afar. After three years as a professional, Spieth says tentatively, “It is still very early on, hopefully, in a career that is as long and—hopefully—somewhere near half as successful as Mr. Nicklaus.” Even so, he admits, “it can be a grind.”

How so? “As much as we love what we do because of the adrenaline rush of being in contention,” Spieth continues, “having important putts or shots, or trying to control the most minor club-face rotations to get the ball to go where you are looking—that can be a mental grind week after week.”

Add to that the physical toll of coiling and uncoiling in a violent swing thousands of times per week. Spieth might not know that part yet, Day offers, but at 28, “I have battled injuries in my career, so I finally said, ‘O.K., I need to take control of what I am doing.’” He has disciplined his diet and prioritized fitness “to extend the longevity of my career. And hopefully one day, stay at the top as long as Jack did.”

As they talk, a certain note rings again and again. Call it stoic, call it self-reliant, it has to do with control, mastery of one’s own fate, captaincy of one’s own ship. Built tall and solid as a tight end, Nicklaus was a forerunner of today’s muscular, health-conscious tour pros in an era of chain-smoking, hard-drinking golf hustlers. Like Day and Spieth, he excelled at a number of sports in his youth, and chose golf for reasons of temperament.

“Baseball was probably my best sport when I was growing up,” Nicklaus says, but he hated to have his playing schedule in the hands of other kids. In those days of pickup ball, before adults organized the fun out of childhood, a game on the playground called for 9 in the morning might fizzle out for lack of players after 90 minutes spent standing around. “But I could go to the golf course at any hour I wanted to go,” he continues, “and I didn’t come home until my mom grabbed my ear and yanked me home.” Nicklaus “loved basketball,” and also “played quarterback until I figured out my hands weren’t big enough.” Golf won out because it “was the only sport that I could go do by myself, do what I wanted to do, do what I needed to do and get my own reward out of my own effort.” Spieth has a version of the same story: “I think back to what Mr. Nicklaus was saying about how your toughest competitor is yourself. I loved team sports, but I love being able to control my own destiny. The work that I put in ahead of time was either going to come out and I was going to be successful—or I was going to try and fail and learn how to succeed the next time.”

The Day version: “I definitely like the solitude of golf. Being able to be out here on the golf course and you are just you and yourself and your thoughts. That’s when you know, ‘Hey, I can push myself a little bit harder.’”

Put golfers from yesterday and today around a table and, inevitably, you will hear a lot about engineering. Unlike the hardwood driver he carried for most of his career, a modern golf club sends a ball flying as if struck with a “trampoline,” Nicklaus says. And the golf balls themselves are miraculous compared with the ones he once played with. As Day and Spieth listen dumbfounded, the legend recounts his methods for sorting a shipment of balls into keepers and duds. Even in a single box, the balls could come slightly different in size—and dramatically different in flight path.

Imperfect technology influenced styles of play, from Palmer’s swashbuckling to Watson’s wedge magic to the slash-and-rescue of Seve Ballesteros. Nicklaus was known for the mistakes he didn’t make and for the miracle shots that he made look easy. He could hit the ball high and hit it low, bend it right or left, and he always seemed to know which shot to hit at which moment. He made an art of what’s known as “course management”—conforming his play to the conditions at hand.

“I have a question,” Day ventures. “For different golf courses, did you have different sets” of clubs?

“Different what?” Nicklaus parries.

“Did you have different sets made for different golf courses?” Day repeats, for the idea of tailoring clubs to the demands of specific courses is common among today’s top pros. Nicklaus explains that he played different clubs in different countries, because his sponsorship deals changed from England to Australia to the U.S. He adjusted to the manufacturer, not the other way around.

If that astonishes the current champions, Nicklaus simply recalls golf as played in even earlier generations. The legendary Bobby Jones, founder of the Masters, discovered after his playing career was over that his 4-iron was weighted differently from his other clubs, Nicklaus recounts—which finally explained why Jones always had such trouble with that club.

And the players themselves are highly engineered today. The ever quotable Trevino divides the golf world between the “round bellies” of the past and the “flat bellies” of the contemporary game. Time in the gym is as much a part of a modern pro’s schedule as time on the practice green. Nicklaus appreciates the athleticism of the new era but worries that professional golf might lose its connection with the game as played by mere mortals. “The average golfer has a harder time relating to today’s game,” he says. In the old days, the pros might play a practice round with the club champion at the country club hosting a tour event. “I would hit the ball 10 or 15 yards past [the amateur], but we could make a game. Today, I can’t imagine seeing any club champion making a game with these guys.” The other great change in golf: the money. When Nicklaus won the first of his record six Masters championships in 1963, his purse was $20,000. For his 1986 title, he pocketed $144,000. Spieth took home $1.8 million for winning in 2015. With endorsement deals worth many times the prize money, top golfers are highly successful small businesses unto themselves. As a result, even young players spend a lot of time thinking about philanthropy.

Day and his wife Ellie are patrons of the Brighter Days Foundation, which supports charities around their Ohio home and promotes golf among young Australians. Spieth’s family foundation emphasizes children with special needs—like his beloved younger sister, who makes frequent appearances in her brother’s social media—military families and junior golf. Both men salute the example of Nicklaus, who, along with Palmer, pioneered the rise of golfers as business moguls and athletes as philanthropists.

And Nicklaus repays the compliment. The ultimate key to sustained excellence, he says, is balance, and “I think both of these guys right here have figured it out already. You know, golf is a game, and it is only a game. It’s a great game, and it will dominate a great part of their lives.” But not all of it.

“My family was a great diversion for me. My business interests were a great diversion.” Promoting his sport and his charities have been great diversions.

The conversation was drawing to an end. If, God forbid, the magic finally ran out for them tomorrow, where would they want to play their final round of golf? For Day and Spieth, the answer was easy: Augusta National, the home of the Masters Tournament.

For Nicklaus, something different: “Pebble Beach,” he says.

“He wins the Masters six times, so [Augusta National] is old news now,” Spieth says with a laugh.

“It’s a pretty hard choice,” Nicklaus allows. “I hope I don’t have to make it soon.”•