Fidel Castro was every word in the book. The longtime Cuban leader was a revolutionary to many, a dictator to many others. A reader and a thinker as well, Castro, who died on Nov. 25 at 90, was famous for his oratory and infamous for his verbal lashes against his enemies. But the master of the word was also a master of the image.

Below are six portraits of Castro made between 1959 and 1995 by photographers who spent variously short or significant amounts of time with him. They are paired with their written accounts, found in photo books and magazine articles published years ago or learned in recent interviews. As singles, they are moments of intimacy in a long life spent in front of crowds. Together they offer another way into the mind of one of the most divisive figures of the last century.

***

‘A Relaxed Man, Very Human’

Alberto Korda was a successful studio photographer focused on fashion when the revolution in Cuba found him. He would quickly begin work as a photographer for the newspaper Revolución and eventually become one of Castro’s photographers for a decade. While he largely made his name for the portrait of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, then one of Castro’s confidants and partners, Korda captured some of the most intimate moments of Castro’s rise.

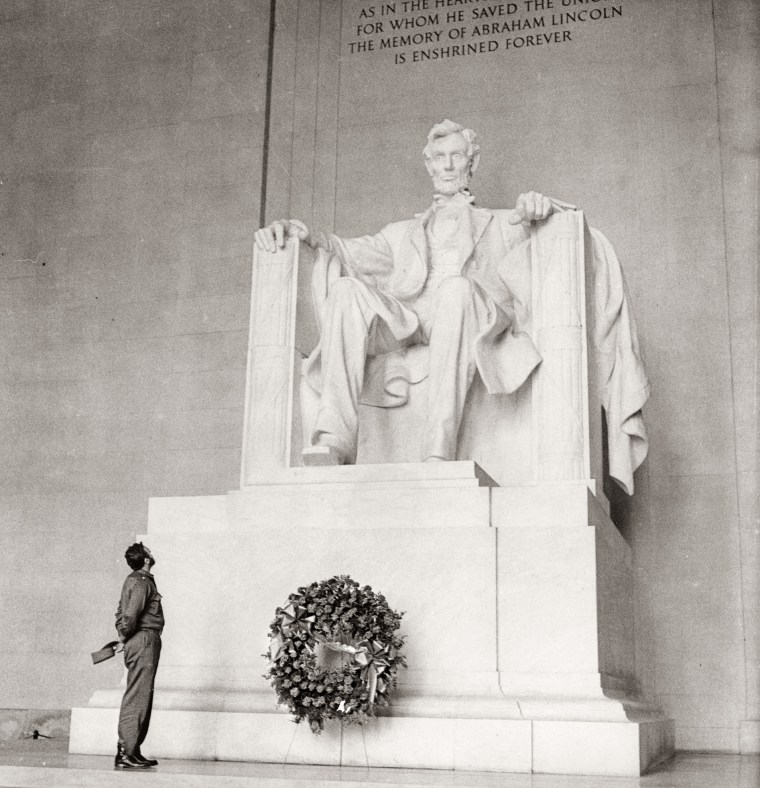

Korda shadowed Castro during an April 1959 trip to the U.S., at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. It had been about three months since the revolution toppled U.S.-backed President Fulgencio Batista, and Castro’s anti-American speeches and alliances with the island’s leftists were less than appreciated around Washington, where he was refused a meeting with President Dwight D. Eisenhower. At one point, Castro stopped at the Lincoln Memorial. At its base, where a wreath was placed, the young leader was photographed in his standard fatigues, cap removed, gazing up.

The photographer called the picture “David and Goliath,” he recalls in the book Cuba by Korda. Speaking of their bond, he is quoted: “From the day I gave a copy to Fidel, he never contacted me at the newspaper but rang me directly. I didn’t become his official photographer; no, I became his personal photographer. I never had a title or a salary. We were like friends. From then on, it wasn’t the leader giving orders I tried to photograph, but a relaxed man, very human, interested in everything and everyone.”

***

‘An Extraordinary Experience’

American photographer Lee Lockwood enjoyed some of the most prized and early access to the man who would rise to rule Cuba for decades. He was there on Dec. 31, 1958, the day before Batista’s ouster. He returned several times over the next decade, frequently engaging in deep discussions with Castro and spending days at a time in his orbit.

It was in 1965 that Lockwood, who was promised an interview, eventually got what became marathon talks lasting seven days. In his 1967 book Castro’s Cuba, Cuba’s Fidel, Lockwood describes in great detail his talks with Castro, which occurred at a white, L-shaped ranch home on what was then called the “Isle of Pines,” an island now known as the “Isle of Youth.” It was at this retreat that he shot this picture of a bare-chested and bearded Castro as he attempted a chin-up.

The pair would stay up talking “long after everyone else had gone to bed,” Lockwood writes, calling a conversation with Castro “an extraordinary experience and, until you get used to it, a most unnerving one.” Lockwood explains that in publishing the full transcript of that week’s interviews, paired with this picture and similar ones, he would allow Castro to be seen and heard for himself. “We don’t like Castro, so we close our eyes and hold our ears. Yet if he really is our enemy, as dangerous to us as we are told he is, then it seems to me we ought to know as much about him as possible,” he writes. “And if he is not—then that fact should be known. Whether one agrees or disagrees with his ideas, the best way to begin understanding a man is by listening to what he has to say.”

***

‘A Guy In Control of His Message’

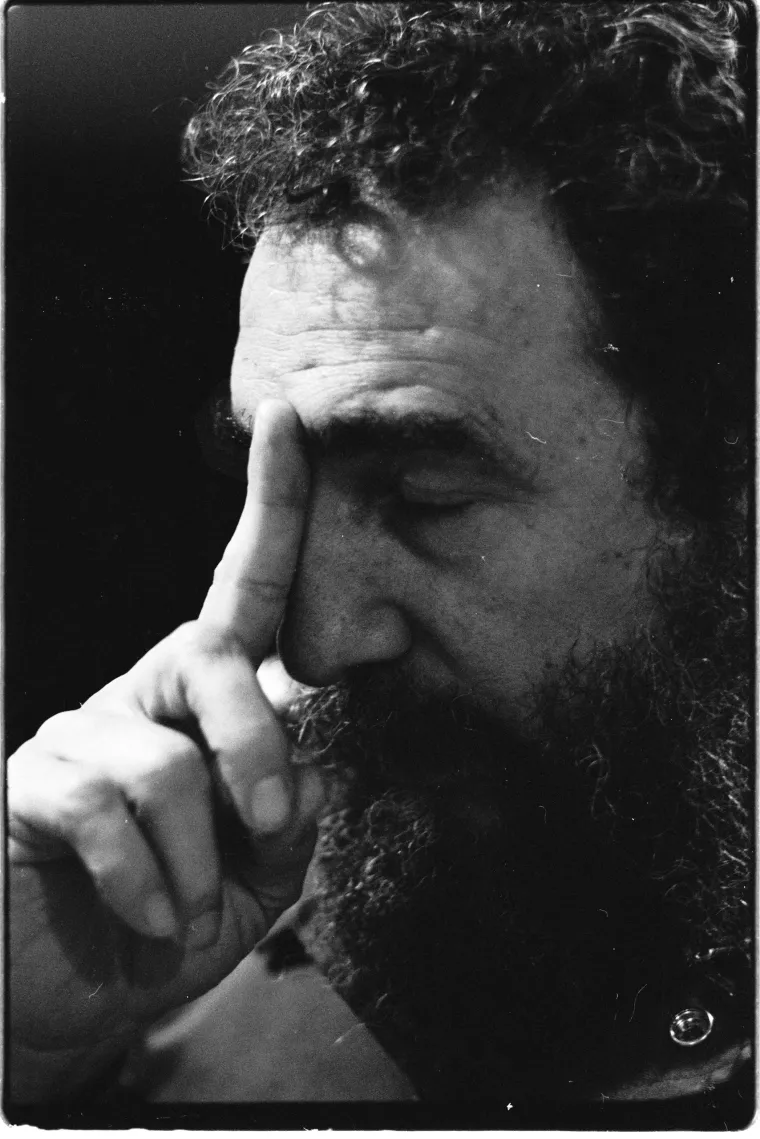

David Hume Kennerly was on assignment for TIME in December 1979 when the magazine’s editor, Henry Grunwald, got a sit-down with Castro. A first interview occurred in Castro’s office in Havana. The second was at a nice—but not luxurious—compound outside the capital where the group was staying. “Castro was late for the second interview,” Kennerly told TIME in the days following Castro’s death. “Sunburned, he walked in with an ice chest full of lobsters that were freshly caught. He announced that he had captured them himself. It was a very friendly act.”

As many others do over the years, Kennerly remembers a long discussion. So long that it would become difficult to take pictures of Castro. “He would take pauses. He would engage his brain before his lips started moving. He was deliberate. In that picture, he was thinking about a response to a question,” Kennerly says. “I never had any sense that he wasn’t totally aware of what he was going to say. He definitely was a guy in control of his message. He knew he was a bigger-than-life character and he played it up. And he knew what a good picture was, I’m sure.”

***

‘I Cannot Play Myself’

Yousuf Karsh is one of photography’s finest portraitists, and many of the most important newsmakers of the 20th century sat for him. Castro’s turn came in 1971. The photographer, who died in 2002, described the scene in the 2009 book Regarding Heroes. Days would pass between the moment he set up his equipment in Castro’s office—”a simple ceremonial room with a few bookshelves and walls so stark as to suggest a barracks”—and the moment his subject would arrive in front of his lens.

Castro became available on the last scheduled day of Karsh’s trip. He looked “grave and tired,” Karsh wrote, and offered an apology for the delay. “He was taller than he appeared in photographs.” The two shook hands and Castro removed his belt and pistol. “As I readied the camera, I suggested that, to start, he might try to recapture the moods of our first moments together,” Karsh explained. “I’m sorry, I cannot,” Castro told him. “I am not a good enough actor. I cannot play myself.” The portrait session would go on for more than three hours, Karsh noted. “From time to time we would stop to refresh ourselves with Cuban rum and Coke.”

“Tell me,” he recalled Castro saying, “about photographing Helen Keller.” He would also ask about Camus, Churchill, Cocteau and, of course, Hemingway. As Karsh told it, “I was impressed that Castro—a revolutionary—should have made room in his life for these creative luminaries.”

***

‘He Only Missed One’

In 1984, veteran conflict photographer Eddie Adams went to Cuba to photograph Castro for an interview appearing in Parade, the Sunday supplement. But two weeks passed with no Castro, so the reporter and Adams went back to New York. The photographer made his disdain clear before he boarded the flight home. In the days that followed, they were urged to return to Havana. On the ground, Adams made a portrait of the Cuban leader while on a duck hunt, of all things, at Castro’s retreat in the countryside. Here, they are shown together.

In a later interview, Adams said Castro killed 76 ducks in just three hours: “He only missed one, he was really upset.” That night, they ate duck. At one point during dinner, as described in TIME, Castro told Adams, “I heard you had a nasty temper. Why haven’t I seen it?” The photographer replied sharply, “Because now I’ve got the pictures.”

***

‘Oh, We Shot Him’

In February 1995, the photographer David Burnett traveled to Havana on a TIME assignment that included an interview with a welcoming Castro. The magazine’s team had arrived in the afternoon and was being walked around the palace. “That’s when we saw this painting,” Burnett recalls, this hulking mural of the Sierra Maestra mountains where the revolution began. Castro walked up to the artwork, his back toward his guests. Burnett “was clawing at the writers not to get too close like, ‘don’t get in my shot.’”

Castro then launched into a short tale about how the painting came to be situated there. “He said the problem was the painting was bigger than the wall that the architect had arranged for it to go on, and everybody started laughing,” Burnett remembers. Asked about his response, Castro said, “Oh, we shot him.” Then he broke into laughter. “Of course, that was a joke,” Burnett adds, “and they managed to wedge it into another hallway.”

“It was so seldom that you had a chance to combine something that had a little sense of the symbolic with the real,” Burnett says of this image. “This was just a moment where you could say, even from behind, everybody knows who this is.” Whatever his politics, Burnett says of Castro, he was “someone you just had to be in the room with you and you would have a picture.” The hard part? Getting into that room.