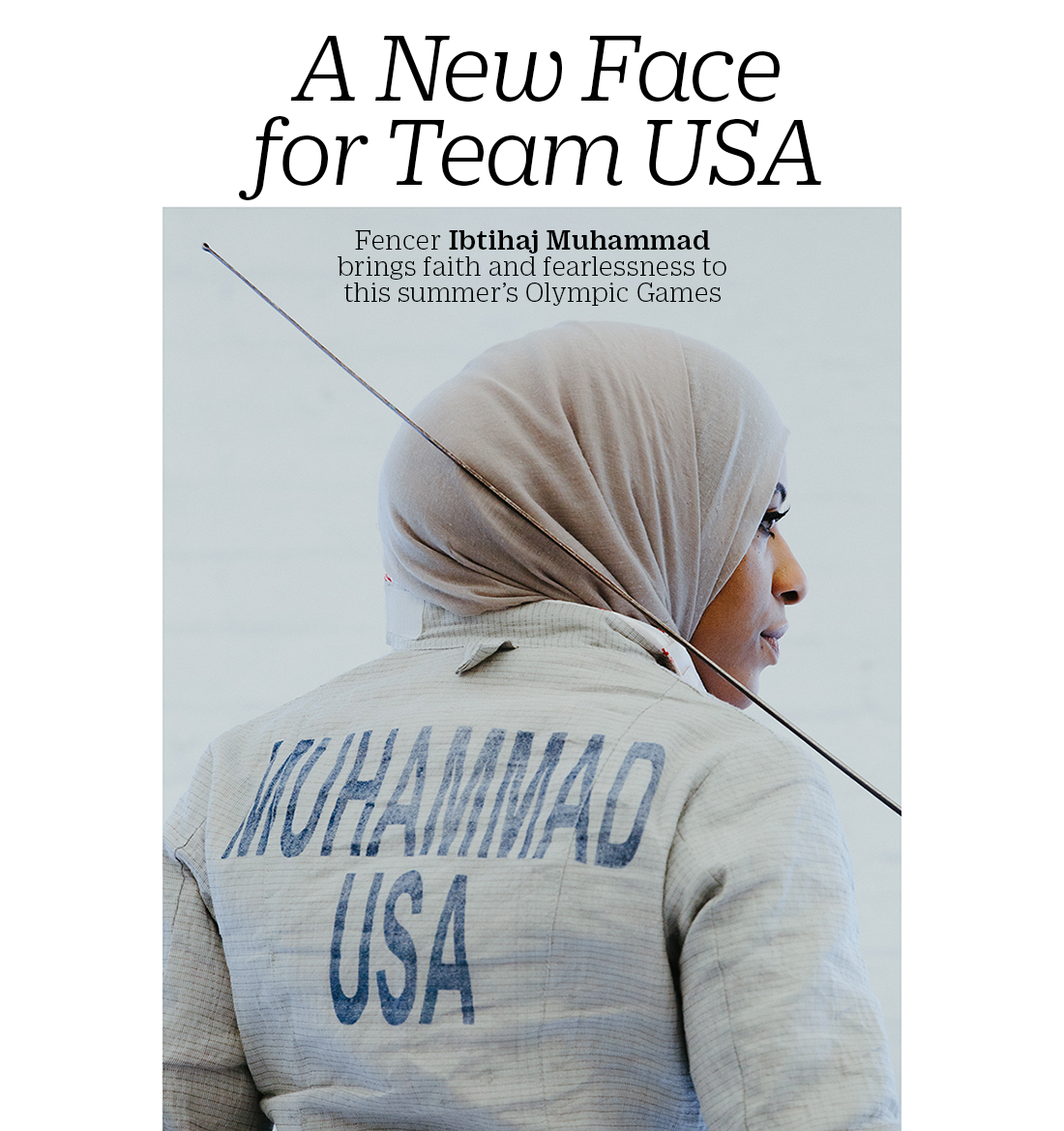

By Sean Gregory | Photographs by Daniel Shea for TIME

On Aug. 5, more than 10,500 of the greatest athletes in the world will stream into Maracanã Stadium for the opening ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Give or take a few samba dancers, the scene in Rio de Janeiro will look much like all the other Olympic pageants before it, save for one crucial detail: for the first time, a member of Team USA will be wearing a hijab. The fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, a Muslim from New Jersey, earned that distinction in late January when she clinched a spot in the Games at a tournament in Athens. Days later, President Obama called her out by name during the first visit of his presidency to a U.S. mosque.

Less than a week after Obama’s shout-out, Muhammad sits unnoticed at a Manhattan Starbucks, talking about something that scares her far more than a sword darting toward her face. “If Donald Trump had his way, America would be white,” Muhammad says between sips of a skinny hazelnut latte. “And there wouldn’t be any color. And there wouldn’t be any diversity here.”

This is charged turf for an Olympian. These athletes, the bulk of whom attract attention only once every four years, tend to shy away from politics. Even a whiff of controversy has the potential to turn off potential fans and alienate the corporate sponsors that help subsidize their dreams. But Trump’s rise to the front of the Republican presidential pack, along with his call to temporarily ban Muslims from entering the U.S., is more than Muhammad can abide.

“When you incite hateful speech and rhetoric like that, the people who say it never think about the repercussions and how that affects Muslims,” says Muhammad. “Specifically Muslim women who wear their religion every single day. So then you start to think, Am I going to be safe?”

With that, Muhammad touches on the critical issue that sets her apart from all the other fantastically talented, maniacally driven members of Team USA. The scarf covering her head is, above all, a deeply personal statement of her faith. But it is also a decidedly public signal of her beliefs: to supporters, it’s a sign of arrival; to detractors, it’s a mark of otherness. It is the reason millions of Americans are cheering for a sport that ranks somewhere below darts in the public consciousness.

“I was jumping up and down, and immediately starting texting friends and calling family members,” says Edina Lekovic of the Muslim Public Affairs Council, an advocacy organization. “This is such a moment of pride and progress, and there’s no going back.”

Muhammad, 30, is the third of five children raised outside New York City in the New Jersey suburb of Maplewood. Her mother Denise, an elementary school special-education teacher, and her father Eugene, a retired narcotics detective in Newark, both converted to Islam before they met.

The Muhammads encouraged their kids to play sports, and Ibtihaj was particularly competitive with her brother Qareeb, who is one year older. “I owe my athletic drive to my brother,” she says. “Because I was always trying to run faster than him or jump higher than him.”

The bouts got so intense, Qareeb once jumped off a patio roof into the family’s backyard swimming pool to prove he was more daring than his younger sister. He delighted in his victories. “I spent a lot of my childhood crying,” says Muhammad. “My brother picked on me a lot. I think it was his goal to make me cry every day.”

Those sibling feuds helped spark an active streak, and Muhammad played softball and volleyball and ran track growing up. But unlike her teammates, Muhammad would wear her uniform over pants and long-sleeve shirts and keep her hijab fixed in place to accommodate Islam’s dictates about modest dress.

The alterations made her feel as if she weren’t fully part of the team. “When we think about the concept of a uniform, this sense of camaraderie that can be built around wearing the same thing, I don’t think I was able to capture that as a kid,” says Muhammad. “When I would walk into a gym with other kids who have on tank tops and shorts, here I am with the hijab, with long sleeves and long pants. That in itself can be ostracizing.”

Her life changed at a stoplight. Paused at a red, Denise looked over and noticed that the car to her right was filled with students from the local Columbia High School holding swords and wearing masks. It was one of those lightbulb moments. Denise started researching fencing online and took Ibtihaj, then in eighth grade, to meet the coach. It felt like the perfect solution for her athletic daughter: everyone’s body was covered, and with a mask, the hijab wouldn’t stand out. “It was absolutely ideal for us,” says Denise.

Or so it seemed. At high school fencing meets, Muhammad was often the only African American. “I remember going to competitions as a kid and people commenting on me being black, me being Muslim,” she recalls. “Parents asking whether or not it was O.K. for me to fence in my hijab, if in some way it would jeopardize someone else’s safety. As a child, that can be kind of traumatizing.”

It was offhand remark — a parent at a competition telling Muhammad there were other black people who fenced — that led her to find what became her second home. After Muhammad told her mom about the comment, Denise discovered Peter Westbrook, a fencer who had won a bronze medal at the 1984 Olympics and who now runs a nonprofit fencing club in New York. The club has a track record of turning kids from nontraditional fencing backgrounds into champions: dozens of alumni have gone on to fence in college, and a half-dozen have qualified for the Olympics.

Soon, Muhammad was making regular train commutes into New York. Westbrook turned her into a saber fencer, one of competition fencing’s three disciplines along with épée and foil. In saber, a fencer can score by hitting an opponent’s target area (the entire body above the waist, including the head but excluding the hands) with any part of the blade, not just the tip, like in the sport’s other disciplines. This makes saber the fastest of the three, requiring the ability to land and defend mile-a-minute thwacks with a sword. Turns out Muhammad had a knack for it. “When she’s fencing, she’s as ornery as hell,” says Westbrook. “With a saber in her hand, there’s not anyone meaner than her.”

Muhammad fenced at Duke, where she received a partial academic scholarship and became an All-American. But she failed to qualify for the 2012 Olympics; she was America’s fourth-ranked saber fencer, and only the top two qualified for the Games. Most people close to her figured she would use her degrees in international relations and African and African-American studies to settle into a traditional career. And she took some tentative steps in that direction.

In 2014, Muhammad founded Louella, a clothing line that aims to modernize the staid offerings typically available in what’s known as the “modest fashion” industry. The idea for the company, which is named after her grandmother, came after searches for floor-length dresses to wear at speaking engagements left her unsatisfied.

“There are tons of Muslim-clothing companies out there,” says Muhammad. “But I felt as though they were never anything me or my sisters or my friends would wear. They’re, like, dowdy and dark.” Her brother Qareeb — the one who used to pick on her — had some connections in Los Angeles and now helps run Louella from the West Coast. Muhammad, who during our conversation is wearing a beige hijab and a blue jean shirt and carries both Louis Vuitton and Louella bags, says the company is profitable: according to Qareeb, Louella has generated approximately $500,000 in sales.

“I know very few women who wear burqas and black,” says Muhammad. “But when Americans think of who a Muslim woman is, that’s the first thing they probably think. It’s O.K. to wear a hijab and be different and challenge these norms, these misconceptions of who we are.”

But Muhammad couldn’t shake the fencing bug. “There’s something about that swashbuckling,” says Denise. “It’s addictive.” Muhammad won her first international medal, a silver, at a World Cup event in 2013, and has made steady improvement since. She is now the seventh-ranked saber fencer in the world.

“She’s incredibly important as a symbol of empowerment,” says Dalia Mogahed, research director at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, a think tank in Washington that studies Muslim issues. “That you can do anything you want, regardless of faith, or how you choose to practice your faith.”

Back sipping her latte, Muhammad is accepting, almost welcoming, of the public glare. She recently signed a sponsorship deal with Dick’s Sporting Goods and is in negotiations with two other Fortune 500 companies. She hopes to inspire young Muslim girls to pick up sports, and to serve as the role model she never had. “If I had people who could challenge that notion that I didn’t belong, if I had athletes I could see,” says Muhammad, “I feel like it definitely would have been easier.”

Yet she doesn’t expect the indignities to fade. “After the Paris attacks, after San Bernardino, Muslims were being kicked off planes across the country,” Muhammad says. “I was like, Oh my gosh, am I going to be one of those people who is going to be asked to leave a flight? Because I made someone else uncomfortable?” She laughs. “If you’re uncomfortable, you’re the one who should get off the plane.” The stares won’t subside either. “That can be really challenging, not ever knowing what someone’s hang-up is,” says Muhammad. “And I’m at a point in my life where I just don’t care. Not interested.”

She is, however, keenly interested in taking on the Republican presidential race. “I still have faith in the greater America that we will not vote someone as ignorant as Donald Trump into office,” Muhammad says. “As a country, we are collectively more intelligent than that. I think he represents everything we aren’t.”

The different parts that comprise the U.S. — the “we” that makes up this patchwork nation — are a particular concern to the first woman who will represent the country while wearing an emblem of a religion many see as its archenemy. On the fencing strip, it’s Muhammad’s job to attack. Outside of it, she just wants to defend. “There’s this notion that somehow having minorities present and successful in our society challenges the success of our country,” Muhammad says. “And that’s frustrating to me. That you have minorities who for so long have been oppressed, who for so long have been confined to particular spaces breaking out of these norms and breaking barriers — that’s what makes America great.”