Story by Jonathan D. Woods

Produced by Alexander Ho, Mike Kitner, Jeffrey Kluger, Lothar Krause, Mia Tramz and Jonathan D. Woods

Photograph by Kip Evans | Cinematography by Kip Evans and Brian Hall

![]()

When I first catch a glimpse of Fabien Cousteau, he looks a little like an astronaut on a spacewalk. In fact, he’s 63 ft. below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean at the world’s only habitable underwater science lab, Aquarius, where he is camped out with a team of scientists for a record-breaking stay lasting 31 days.

It’s day 15 of Mission 31, and the ocean explorer and environmentalist, who was kind enough to let me visit, seems very much in his element. Today he’s monitoring the vital signs of coral that’s been exposed to things like fertilizer runoff. “What we found was pretty surprising in terms of why reefs in close proximity to humans are degrading,” says Cousteau.

That’s a big reason he launched this mission. From June 1 to July 2, Cousteau and a revolving team of more than 30 oceanographers, filmmakers and activists—including scientists from MIT, Florida International University and Northeastern University—lived aboard Aquarius, conducting research and filming a documentary about Mission 31 in this marine protected area nine nautical miles off the coast of the Florida Keys.

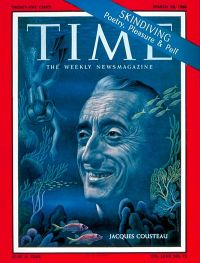

The mission matters a lot to Cousteau. He’s concerned about the state of the oceans, and he wants to make a contribution to our understanding of how pollution and climate change are affecting them. Mission 31 is also a continuation of his family legacy. Fifty years ago, his grandfather, the legendary ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau, led a 30-day underwater mission, during which six aquanauts lived below the surface of the Red Sea and studied the practicality of working on the seafloor. Jacques cared deeply about the ocean, and the lifelong explorer wanted everyone the world over to share his passion. Fabien’s Mission 31 is an answer to that call.

![]()

![]()

Not Your Everyday Dive

Even for experienced divers, the 400-sq.-ft. lab can be challenging to get to. Photojournalist Ed Linsmier and I load our gear onto a spartan boat as its diesel engine growls to life, pushing us out of Islamorada Key. Almost an hour later, we come upon a yellow platform about 30 feet wide. There’s a no trespassing sign, and the faint hum of a generator emanates from the base below a tall mast.

This platform, I soon learn, is partly responsible for keeping the aquanauts aboard Aquarius alive and connected to the mainland. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration first funded Aquarius in the mid-’80s, and it’s been in use by researchers off and on ever since. Inside, six bunks, a kitchen and a toilet provide basic necessities. Over the years, some elements have been added—and today Aquarius even has wi-fi, which sustains a 24/7 live stream, monitored by a team on land. The lab costs approximately $15,000 a day to operate.

As soon as we tie off to a buoy, everyone on deck springs into action. We all have jobs to do. Mine is capturing 360-degree video of our journey, and Linsmier is here to take photographs. Before we can hop into the water, though, we’re instructed to double-check all our equipment. (Given the complex nature of the operation, “the fewer curveballs we throw in the better,” Cousteau tells me later.) It’s a good thing we did, because no sooner do we start our descent than we’re slammed with strong currents—strong enough that attempting to swim against them is futile. That means I have to pull myself down to Aquarius using a line that runs from the surface all the way down to the lab, while also manning my video equipment.

It’s a grueling but exhilarating task, and once we reach a depth of 63 ft., I spot Cousteau with a pair of scientists. The whole scene is astonishing. The seafloor is dotted with equipment, air bottles and support systems. Aquarius is covered with coral and sponges. A small structure adjacent to Aquarius looks to me like a lunar lander. (It’s actually called the Gazebo and serves as an emergency refuge in case Aquarius needs to be evacuated.)

As I watch Cousteau experimenting on coral, the parallels between Mission 31 and Jacques’s 30-day mission in the Red Sea come into focus—as does the realization that 50 years after that first dive, we still know very little about ocean life.

A mere 5% of the world’s oceans have been explored—making the technological advances that have come since Jacques’s time all the more important. Scientists are in a better position than ever before to learn about what pollution and a changing climate are doing to marine life. Computers have made it easier to log data. Sensors the width of a human hair and high-speed cameras help researchers see things in ways the human eye cannot. And underwater-breathing equipment makes aquatic science and recreation possible throughout the world.

Mission 31, for instance, devoted some of its photographic resources to observing predator behavior. In one video, high-speed cameras were able to capture a mantis shrimp eating its prey, which may sound simple but actually involves isolating movements that happen in a fraction of a second. “You have to sit there for hours to get a few milliseconds of natural behavior,” Cousteau told TIME.

![]()

![]()

Mission 31, Accomplished

On July 2, Mission 31 came to a close. Leaving Aquarius was hard for Cousteau. “Emotional,” he says. “You get used to it. Eel, sharks, barracuda parking on your shoulder wondering what you’re doing. Animals getting used to you in their environment.”

The most dramatic part of Mission 31 was its length, of course, but if Cousteau’s team has its way, its impact will be lasting. By the end of Mission 31, the scientists had amassed the equivalent of two years’ worth of research, they say, both because they were spared the travel time going back and forth between land and the ocean floor and because they weren’t limited by ever depleting air tanks.

In their trove: 12 terabytes of data—that’s about 750 at-capacity iPads’ worth—which is enough to produce an estimated 10 new research papers, says Cousteau. Among the things Mission 31’s scientists investigated were predator-prey behavior, the effects of certain nutrients on coral, and the possible presence of hydrocarbons from oil spills, to name a few. If it comes together as they hope, that’s a potentially big contribution to ocean research.

As for what’s next, Aquarius will continue to host researchers for shorter stints. NASA will be down there soon to study human interaction in isolated environments. And for his part, Cousteau hopes someone, sometime soon, launches Mission 32.