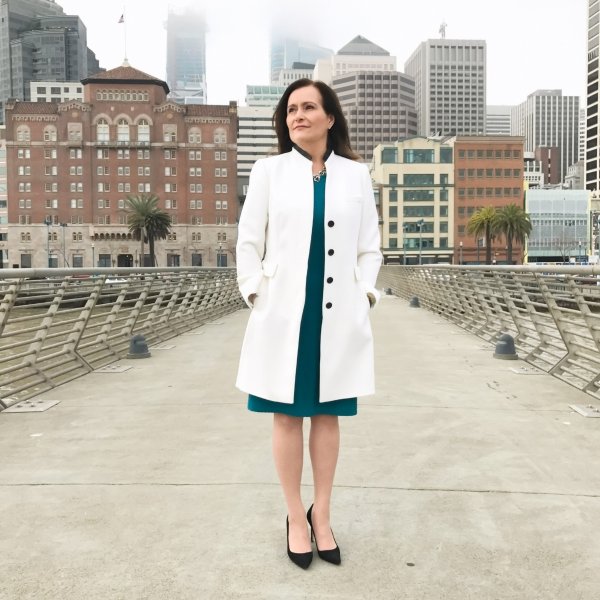

The Explorer

Kathryn Sullivan

First American woman to walk in space

Interview

‘The notion that women might menstruate in orbit drove the whole place up the wall.’

In the early days, as one of the only women in a field camp or on a ship with all guys, I’d get a few reactions. Before, the men had permission to drop some social customs and be kind of locker-room-y, to use vulgar language if they wanted. One reaction was a “You’re ruining my clubhouse” kind of thing. Another was “I don’t know if we’ve got bathroom facilities for you.” That was sort of astonishing. I thought, There’s a tree right over there, and that toilet doesn’t actually care who pulls the handle, and I think this will be fine. Places like a field camp, a research ship, a space shuttle—they are isolated environments for extended periods of time, and I think some men also worried about their wives’ reactions to women now being there.

When we all joined the Astronaut Corps in 1978, NASA had the wisdom to bring in a critical mass—six women, three African Americans, an Asian. So there was a cohort, and we could build a bit of an alliance to tackle some of the issues that come along with adding new people to a close-knit culture.

I’ve heard stories about some of the preparations that NASA had to make to welcome women to the Astronaut Corps. There was an exercise facility that had only ever accommodated men and now was going to need some proportion of the locker room for women. It had a frosted-glass wall facing outward to the street. I don’t think any woman had ever thought of going by there in the evening and gawking to see a silhouette of any of the guys, but as soon as it became apparent that there might be women behind this part of the locker room, there was a realization, like, “Oh, we need to do something about that, because guys might go gawk at women undressing.” Well, wait—why was that not an issue when it was the guys dressing and undressing?

The really amusing stuff came, of course, in the onboard personal hygiene. You’ve packed a Dopp kit—they’d had a man’s shaving kit for every spaceflight up until then. So NASA had a bunch of male engineers trained in the ’50s and ’60s asking themselves, “What’s the female equivalent of a Dopp kit?” I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall as they tried to figure that out! “I don’t know, what does your wife take on vacation?” The notion that women might menstruate in orbit drove the whole place up the wall.

There was a big debate about the dress code for women astronauts. A senior scientist at the Johnson Space Center named Carolyn Huntoon tended to be the go-to woman for advice in all of these moments. She said, “Well, what’s the dress code for the men?” They said, “Oh, we never have a dress code for men astronauts.” “Well, I think you have your answer.”

“What if they wear something we don’t like?” “Well, what do you do if one of the men wears something you don’t like?”

“Oh, well, it’s just not my business.” “I think you have your answer.”

“What do we do if one of these women that we select is married?” “You select her.” “Well, what if her husband doesn’t want to move to Houston?” “What do you do if one of the men’s wives doesn’t want to come?” She had to do that over and over, reminding them it’s just symmetrical, people.

All six of us in that first batch of women felt a self-imposed pressure. One of us would be the first to fly, another would be the first to do a spacewalk—which only a small group of the Astronaut Corps gets to do. We knew our performance would have a big influence on the prospects of the women who would come after us. I was thrilled to be tapped for a spacewalk, but the “first female spacewalker” tag really didn’t matter to me. It was my first spacewalk. And, sadly, my only spacewalk.

After 15 years at NASA, Sullivan became chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and later administrator of the NOAA from 2014 to 2017.