-

The Witches, Stacy Schiff

Little, Brown and Company Best-selling biographer Stacy Schiff (Cleopatra; the Pulitzer-winning Vera) aims her keen research skills at U.S. history in The Witches: Salem, 1692. With her impressive attention to detail and atmosphere, she conjures an eerie vision of the 17th century. Don’t come expecting a satisfying solution to the juiciest mystery about the Salem witch trials of that year—like why on Earth they happened—but Schiff offers an exhaustive look at who, what, where and how. And if she can’t answer the why, it’s unlikely anyone ever will.

-

Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates

Spiegel & Grau In any other year, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s letter to his teenage son about being black in America—a nod to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time—would have been a compelling piece of commentary. This year, it has been an urgent, essential phenomenon as the nation has struggled with police brutality, racial unrest and manifest inequity. Mortal danger is what black men live in, Coates writes, and their—his—existence is a fearful one. There is no tidy ending for the book, or for reality, but perhaps Coates felt some small piece of closure when he was able to dedicate his National Book Award to Prince Jones, his own friend who was killed by police in Maryland in 2000.

-

The Givenness of Things, Marilynne Robinson

Farrar, Straus and Giroux Fiction readers have long admired the way characters in Robinson’s novels, like the Pulitzer-winning Gilead, are animated by a faith that is deeply considered yet never overbearing. In her new collection of essays, Robinson lifts the curtain on her own theological thinking. She engages with the great thinkers of the Protestant Reformation (Luther, of course, but also Shakespeare) while raising critical questions about the current state of Christianity in America, where the zeal of some believers leaves her concerned. But she’s hopeful, too. On topics ranging from servanthood to grace, she reminds us that practicing Protestantism, so commonplace in 21st-century America, began as a frighteningly, passionately radical act.

-

Destiny & Power, Jon Meacham

Random House To the casual observer, George H. W. Bush appears one of our less memorable presidents–sandwiched between the glamorous Reagan and the charismatic Clinton, and then overshadowed by his two-termer son. But in Meacham’s telling, Bush’s lack of verve becomes his greatest asset. Drawing upon expansive access to Bush and his diaries, Meacham depicts Bush as a poignantly paradoxical figure. Bush, here, is imbued with the values of the Greatest Generation, and then elevated to the nation’s highest office at the moment those values lost their primacy. Through one man’s long journey through politics, we see America’s changing attitudes toward power and duty in the twentieth century.

-

Black Man in a White Coat, Damon Tweedy

Picador One of Tweedy’s first memorable experiences at Duke Medical School had nothing to do with cadavers or practice patients. It was when his professor mistook him for a janitor, on hand in the classroom, apparently, to change a burnt-out lightbulb. Instead of making Tweedy angry, the slight filled him with anxiety, and a propulsive (but clearly incorrect) fear that he was not good enough to get where he goes: through Duke, to Yale Law School and eventually into practice as a psychiatrist. This clear-eyed memoir doesn’t just deal with Tweedy’s own experiences at the intersection of race and medicine—he takes on the backgrounds of his patients, too.

-

Being Nixon, Evan Thomas

Random House Richard M. Nixon is one of the most endlessly psychoanalyzed figures in recent history, so credit to Thomas for making an analysis of the life of the 37th President feel new and vital. Thomas covers Nixon’s painful childhood, his vexed relationship with Dwight Eisenhower and his wilderness years and his presidency (colored through Nixon’s own words from recently-released tapes) in a book that’s fairminded but not overly forgiving. The book’s approach can be summed up in its brief accounting of Nixon’s final years in a half-exile, half-public life. Being Nixon is not wistful, but it’s a picture of a human, rather than a cartoon villain.

-

The Brothers, Masha Gessen

Riverhead Books This is the story of two of the most despised men in recent history: the Tsarnaev brothers, Tamerlan and Dzhokar, who carried out the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. They created one kind of chaos, but they came out of another: descended from Chechens deported by Stalin to Central Asia, the Tsarnaev family emigrated to the U.S. from Dagestan in 1994 and settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There the brothers entered a demimonde rarely seen or written about, of young immigrants trying and failing to find a foothold, an identity, a career, even a stable address in a new country. A tremendous piece of tireless reporting, The Brothers doesn’t offer easy answers, but it fills in the missing context around an otherwise inexplicable act of grotesque violence.

-

Negroland, Margo Jefferson

Pantheon Books Jefferson’s upbringing in 1950s Chicago was almost idyllic. Almost. Home life was cozy enough—her physician father and socialite mother were members of the city’s black bourgeoisie, and she and her sister were well fed, well cared for, pointedly well dressed. But the tensions of the time were inescapable, and with them came personal pressures that eventually sunk Jefferson into depression—yet one more thing she wasn’t “allowed” to have as a black woman. Jefferson uses the long poem format, alternating between poetry and prose, despair and triumph, to tell a story that is as compelling for the reader as it seems cathartic for her.

-

Barbarian Days, William Finnegan

Random House How many ways can you describe a wave? You’ll never get tired of watching Finnegan do it. A staff writer at The New Yorker, he leads a counterlife as an obsessive surfer, traveling around the world, throwing his vulnerable, merely human body into line after line of waves in search of transient moments of grace. Finnegan grew up in California and Hawaii but searches out spots in Australia, Fiji, South Africa, Majorca, each of which is a tiny, fractally complex universe of clashing swells and currents and wind and underwater geography. “The close, painstaking study of a tiny patch of coast,” he writes, “every eddy and angle, even down to individual rocks, and in every combination of tide and wind and swell…is the basic occupation of surfers at their local break.” It’s an occupation that has never before been described with this tenderness and deftness.

-

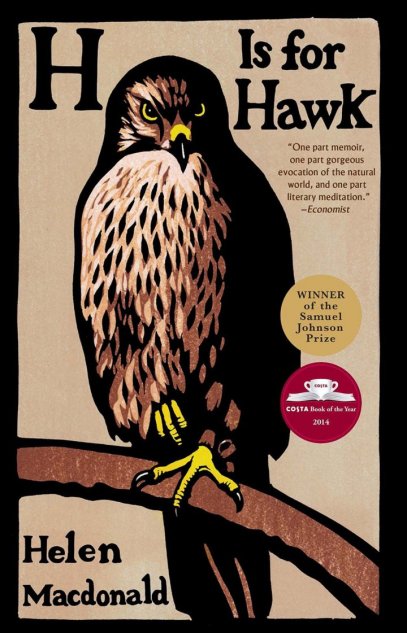

H Is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald

Grove Press This is a memoir by a woman who lost a parent and found a hawk. Macdonald, a scholar at Cambridge University, went to pieces after her father died, and in her mourning she did something unexpected: she purchased a goshawk. Macdonald was already an experienced handler of birds, but goshawks are large and wild and fierce even by hawk standards, and she’d never tried to tame one before. The war of wills that ensued may have made the goshawk (Macdonald names her Mabel) tamer, but it made Macdonald wilder too. It also proved strangely healing and redemptive, and she describes her avian adversary in language so breathtaking and immediate, you’d swear one was sitting on your shoulder.