-

NASA selects first astronauts for private spacecraft

NASA—AP In this image made from a video provided by NASA, astronauts, from left, Bob Behnken, Eric Boe, Doug Hurley and Suni Williams gather for an interview at the Johnson Space Center in Houston on July 10, 2015. NASA’s astronauts have always gotten to space one of two ways: aboard NASA’s own spacecraft or increasingly since the space shuttle was retired in 2011, aboard Russia’s Soyuz rocket. But space is going private. In 2014, after a heated competition, NASA announced that Los Angeles-based SpaceX and Seattle-based Boeing would be the private builders of the next generation of spacecraft to fly astronauts to the International Space Station. Winning the contract, of course, is not the same as executing it, and the ships must first be tested and proven flightworthy. Still, in July, NASA signaled its confidence in the contractors by announcing the first four astronauts who will fly the new vehicles. All four—Robert Behnken, Eric Boe, Douglas Hurley and Sunita Williams—are space station veterans. And all four are anxious to get their hands on the keys to the new machines. More than four years after the last shuttle flew, Cape Canaveral will once again be a busy place.

-

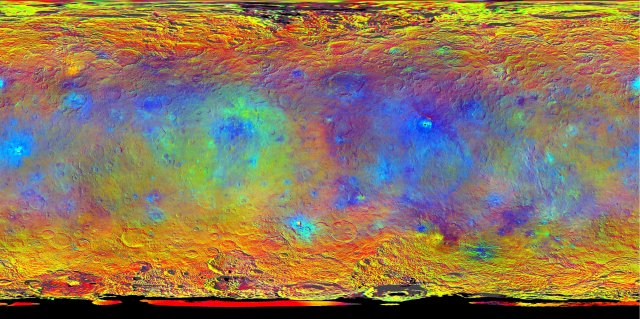

Dawn spacecraft maps dwarf planet Ceres

NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/ID This map-projected view of Ceres was created from images taken by NASA's Dawn spacecraft during its high-altitude mapping orbit, in August and Sept. of 2015. Why build two spacecraft when one can do two jobs? That’s the feat the Dawn spacecraft achieved in March when it went into orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. Launched in 2007, Dawn first flew to the asteroid Vesta, and entered orbit there in 2011. But at the end of its 14-month stay, its systems were working well enough that NASA fired its thrusters, nudged it out of Vesta orbit, and sent it on to Ceres. No spacecraft had visited either body before. And for that matter, no spacecraft had visited any dwarf planet before either. Dawn’s arrival at Ceres beat New Horizons’ arrival at the dwarf planet Pluto by four months. Bragging rights for Dawn, perhaps, but a good year for both.

-

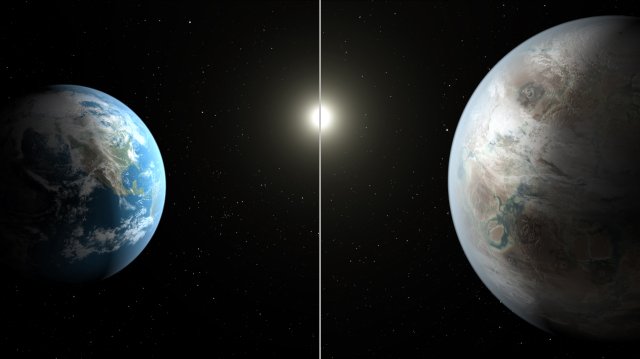

NASA discovers Kepler 452b, most Earth-like planet yet

NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle An artistic concept of Kepler-452b, Earth's Bigger, Older Cousin. It’s not easy being Earth. In order to become the vibrant, biologically active place it is, our home planet had to check some critical boxes: it had to have a solid surface (unlike the gas giants in the outer solar system); it had have enough gravity to hold onto its atmosphere; and it had to exist in the so-called Goldilocks zone around its parent star—the not-too-hot, not-too-cold place where water can be in a liquid state. The planet-hunting Kepler Space telescope, launched in 2009, has discovered thousands of worlds and candidate worlds orbiting other stars in the time it’s been aloft, but the true goal has always been to find a mirror Earth, one that meets all of those same biological criteria. In July, NASA announced it had found the Earthiest world yet—Kepler 452b, a rocky planet 1,400 light years away. Kepler 452b is 60% larger than Earth, which is well within the optimum range. It orbits at such a distance that it makes one revolution around its home star in 385 days—an awful lot like our 365-day year. And that star has the same temperature as our sun—though it is 10% larger. Still, the match is close enough that one NASA scientist described 452b as “an older, bigger cousin of Earth.” Whether the two planets are home to any living, breathing, biological relations remains, for now, a mystery.

-

Deep Space Climate Observer (DSCOVR) goes online

NASA—Getty Images In this handout provided by NASA, Earth is seen from a distance of one million miles by a NASA scientific camera aboard the Deep Space Climate Observatory spacecraft on July 6, 2015. Hovering in space, 1 million miles from Earth, a robot is keeping an eye on you. Actually, it’s keeping an eye on all of us—and, more precisely, what we’re doing to our planet. Formally known as the Deep Space Climate Observatory, it is less formally known as DSCOVR and much less formally as GoreSat, because it was originally proposed in 1998 by then Vice President Al Gore. The satellite was launched in February 2015 and then steered out to what’s known as a Lagrangian Point, a place in space where the gravity of the Earth and Sun cancel each other out, allowing objects simply to hang in place. DSCOVR monitors climate, but it also regularly beams back stunning glossies of our home planet, reminding us of what’s at stake if we don’t take care of the one world we’ve got.

-

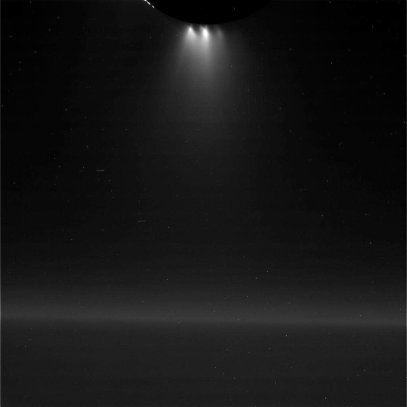

Cassini Saturn probe swoops through an Enceladus plume

NASA/JPL—Caltech/Space Science Institute This unprocessed view of Saturn's moon Enceladus was acquired by NASA's Cassini spacecraft during a close flyby of the icy moon on Oct. 28, 2015. Enceladus is becoming thought of as the coolest little moon the atmosphere has ever known. One of Saturn’s swarm of natural satellites, Enceladus is a frozen world with frosty geysers, which regularly erupt thanks to tidal flexing by Saturn and nearby sister moons. The frost is ordinary water ice, kept liquid beneath Enceladus’s surface by the same squeeze of gravity. There are no existing spacecraft capable of landing on Enceladus, but in late October, the Cassini probe—which has been orbiting Saturn since 2004—did the next best thing, sweeping through one of the geyser plumes to sample the water. The results are not yet known, but the search—as always—is for signs of biology. Whatever the results, the maneuver itself was as nifty a piece of cosmic flying as you’re ever going to see.

-

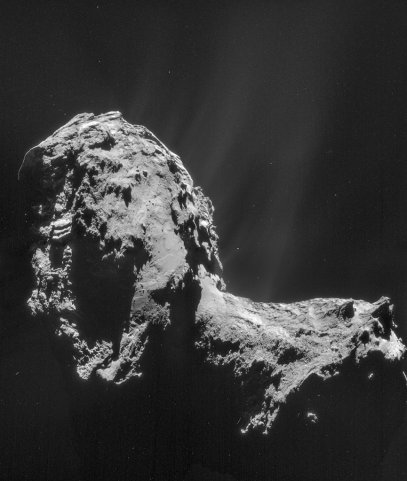

Rosetta orbiter finds molecular oxygen on comet 67P

ESA/ROSETTA/NAVCAM This composite is a mosaic comprising of four individual NAVCAM images taken from 19 miles from the center of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Nov. 20, 2014. Chemistry is all about the details—and as chemistry goes, so goes biology. That’s why it was big news in October when the Rosetta spacecraft, which has been orbiting Comet 67P for roughly a year, detected molecular oxygen—familiar O2 as opposed to O3 (with three oxygen atoms), or single-atom O—in the comet’s vapor. Two-atom oxygen is the kind we breathe and the kind plants produce in the process of photosynthesis. Its existence in comets is one more sign of a life-friendly universe. There are surely no living critters riding aboard Comet 67P. But the discovery improves the odds—at least a little—that they may be out there somewhere.

-

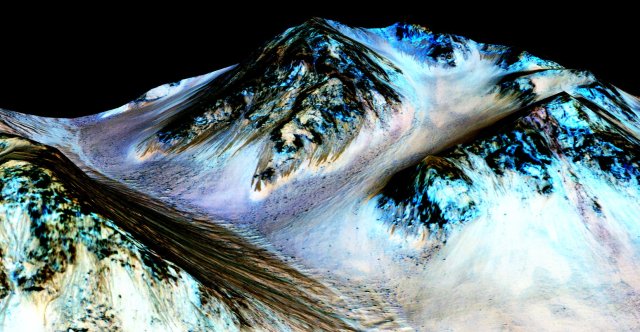

Flowing water is found on Mars

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona In this handout provided by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, dark, narrow streaks on the slopes of Hale Crater are inferred to be formed by seasonal flow of water on surface of present-day Mars. Mars had it all once—warmth, atmosphere, water, the potential to cook up who-knew-what variety of life. But that was a long time ago—more than three billion years ago. Since then Mars lost most of its atmosphere and with it, all its water. Or almost all. A study released in September that analyzed data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter revealed that flowing water exists on Mars today. There’s not much of it, certainly—just some trickles that run along the ground during the Martian summer when frozen, underground deposits thaw and bubble to the surface. But when it comes to biology, a damp Mars is a vastly more hospitable place than an entirely dry Mars. All is not lost, it appears, for a once promising world.

-

New Horizons reconnoiters Pluto

NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft captured this high-resolution enhanced color view of Pluto on July 14, 2015. Call Pluto what you will—planet, dwarf planet, cosmic oddity—it has been a source of fascination ever since its discovery by amateur astronomer Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. But while every planet in the solar system from Mercury to Neptune has been visited by spacecraft from Earth, Pluto never felt the love. That changed on July 14, 2015 when the New Horizons spacecraft, which had been launched from Earth nine years earlier, made its closest approach to Pluto and its flock of five moons. The ship barnstormed Pluto at a distance of just 7,800 mi. (12,500 km), which seems like a lot until you consider it traveled 4.65 billion mi. (7.5 billion km) to get there. That, in case you’re wondering, is a margin of error of .000167%. And that, in turn, is some fine cosmic sharpshooting.

-

Space Station reaches 15 years of continuous occupancy

NASA—Getty Images In this handout provided by NASA, back dropped by planet Earth the International Space Station is seen from NASA space shuttle Endeavour after the station and shuttle began their post-undocking relative separation on May 29, 2011 in space. On an otherwise unremarkable day in November 2000, three men reported for work. Not much news in that, except that the men were an American astronaut and two Russian cosmonauts and their place of business was the then-under-construction International Space Station (ISS). In the 15 years since, 217 other men and women from 17 countries have followed them, with the station—which has grown exponentially and is now a sprawling flying lab larger than a football field—remaining continuously occupied all that time. In the event of an emergency or critical malfunction, the crew could bail out and the ISS could fly empty until it was safe to return. It is a mark of the durability of the huge, improbable machine that that has never been necessary. And it is a mark of the space engineers’ faith in their work that the station could go on being continuously occupied for another ten years—each day marking a new longevity record and another small step forward in the business of space science.

-

Scott Kelly and Misha Kornienko begin one-year mission

Bill Ingalls—NASA/Getty Images Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko of the Russian Federal Space Agency, Russian cosmonaut Gennady Padalka of Roscosmos and NASA Astronaut Scott Kelly pose outside a Soyuz simulator during the second day of qualification exams at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City, Russia on March 5, 2015. You think you’d like to spend a year in space, and maybe you would. But your body would absolutely hate the experience. Human beings were built to live in the gravity well of Earth; move to a zero-g environment and your bones, muscles, heart, eyes, immune system and more go awry. If we’re ever to get to Mars—a two-plus year round trip mission—those biological obstacles have to be overcome. For that reason, American astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian Cosmonaut Misha Kornienko left Earth on March 28, 2015 to spend a year—give or take a couple weeks—aboard the International Space Station. They will return sometime in March of 2016, having completed 5,840—give or take a few—orbits of the Earth. Business trips do not come any longer or any stranger. Watch the documentary series TIME is producing on this historic mission HERE.