Guardians put themselves on the line to defend the ideals sacred to democracy. In 2020, they fought on many fronts. On the front line against COVID-19, the world’s health care workers displayed the best of humanity—selflessness, compassion, stamina, courage—while protecting as much of it as they could. By risking their lives every day for the strangers who arrived at their workplace, they made conspicuous a foundational principle of both medicine and democracy: equality. By their example, health care workers this year guarded more than lives.

In Washington, Dr. Anthony Fauci led not only the battle against COVID-19 but also the fight for truth—clear, consistent messaging being fundamental to public health. With steadfast integrity, Fauci nudged, elided and gently corrected a President used to operating in a reality of his own construction, buoyed by the fervent repetition of lies. (Read more about Dr. Fauci.)

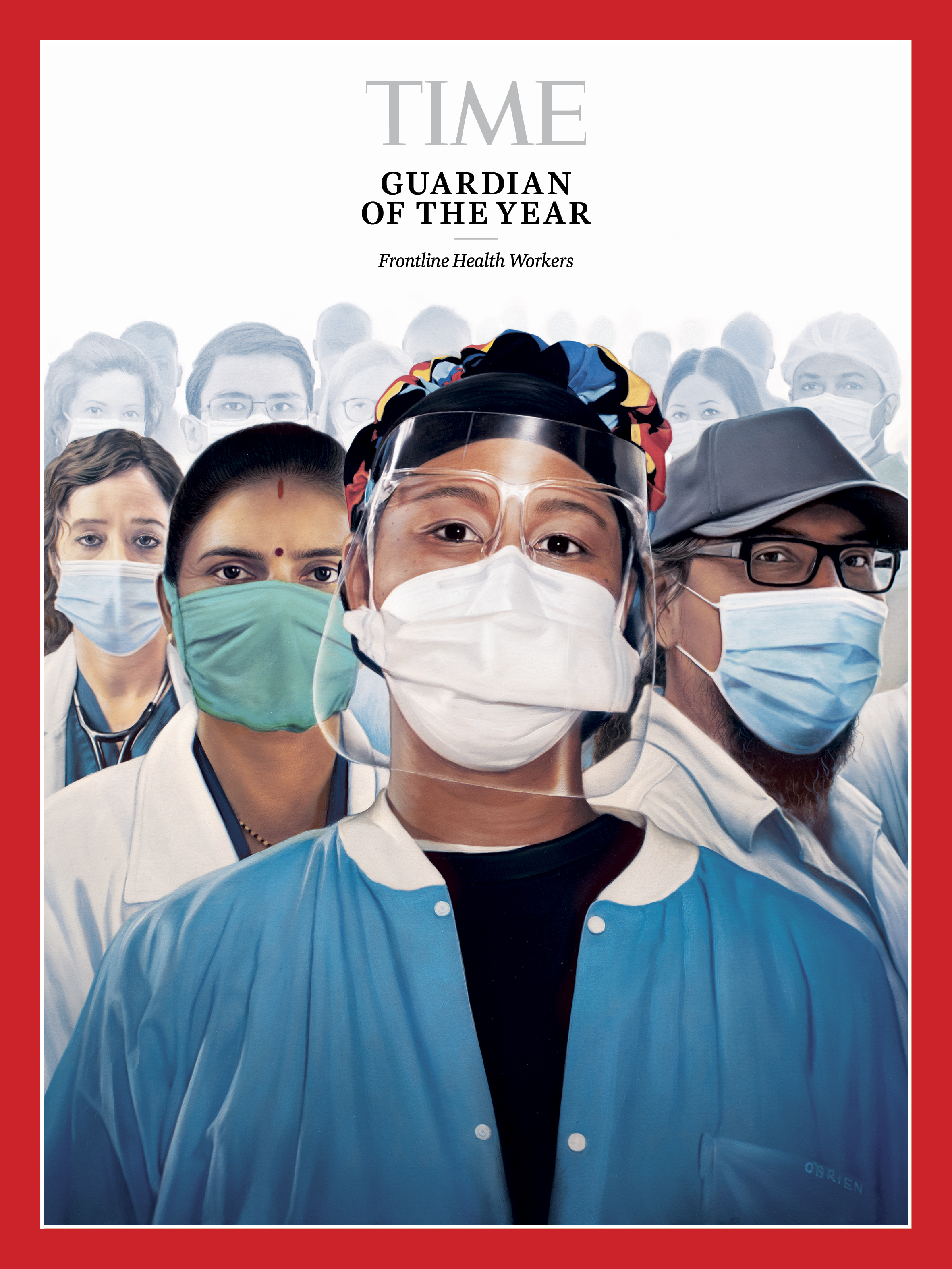

Frontline Health Workers

Human beings don’t always do selflessness well—and in some respects, there’s no reason we should. We’ve got the one life, the one go-round, the one chance to work and play and thrive and look after ourselves and our own. That doesn’t make for a generous, self-denying species; it makes for a grasping, needy, greedy one. And that’s exactly how we behave. Until we don’t.

Evolution may code for self-interest first, but it codes for other things too—for kindness, for empathy, for compassion. There’s a reason we rise up to defend the suffering, to comfort those in sorrow, to gather in the sick and afflicted. And this year—as the coronavirus pandemic burned its deadly path around the world—we’ve risen and comforted and gathered in ways we rarely have before.

The global mobilization to defeat the pandemic has been led by doctors, policymakers, heads of state and more—most notably in the U.S. by Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has been a face and voice of gentle empathy and hard truths. But there are only so many leaders, and a widely available vaccine remains months away. Since COVID-19 first appeared last December in Wuhan, China, this has thus been a more personal, more intimate effort, one conducted patient by patient, bedside by bedside, by uncounted, often anonymous caregivers: pulmonologists, EMTs, school nurses, home health workers, nursing-home staff, community organizers running testing sites, health workers from regions where case counts were low who packed up and raced to places the pandemic was spiking.

“I’ve gotta go,” 44-year-old pulmonologist Dr. Rebecca Martin of Mountain Home, Ark., recalls thinking back in the spring as she watched media coverage of the crisis that was gripping New York City. Martin caught a nearly empty flight to New York, landed in what amounted to a ghost town—no people on the sidewalks, no cars on the roads—and made her way to Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Brooklyn to volunteer her services.

“I’[d] never practiced medicine outside of Arkansas,” she says. “It was terrifying. There was so much we didn’t know about COVID-19.” Back home now, Martin is fighting the U.S.’s third wave in her own hospital, Baxter Regional Medical Center, working 12 to 14-hour days. “We will take care of our community,” she says simply.

Often, taking care of the community has meant not taking care of the self. “I saw more people die this year than I probably saw in the last 10 or 15 years of my career,” says Dr. Alan Roth, 60, chairman of the department of family medicine at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center in Queens, N.Y. Roth contracted the disease back in March and is now suffering from long-hauler syndrome—experiencing crushing fatigue months after the acute phase of the disease passed. But he is standing his post as the third wave crashes over the nation. “I’ve worked seven days a week for many years of my life, but I never have been as physically and emotionally washed out as I am now,” he says.

All over the world, there have been similar displays of dedication, of sacrifice. It hasn’t been health care workers alone who have carried that burden. Teachers, food-service workers, pharmacy employees and others running essential businesses have all done heroic work. But it is the members of the health community who have led the push—taking on the job when the pandemic was new and they were hailed as heroes—with evening cheers from a grateful public. Now the cheers have largely stopped, the public is fatigued, and the frontline workers themselves are sometimes even -resented—seen as somehow responsible for the prohibitions and constrained lives we’ve all had to live. But the workers are pressing on all the same—bone-tired maybe, but smarter and tougher. Their stories are all different. Their courage is shared.

When her phone rang in March, Ornella Calderone, a 33-year-old medical graduate in Turin, Italy, had a feeling the call would change her life. Italy was then the global epicenter of what the World Health Organization had just declared a pandemic, and Calderone offered her services to a hospital in Cremona, one of the country’s hot spots. The call was from the hospital telling her she was very much needed. Two days later, she was in the thick of the fight, working in the pulmonology ward with other novice doctors, tending to COVID-19 patients in critical condition.

“We were forced to absorb the concepts in a very short time, to learn everything right away,” she says. One thing they learned fast was how to offer succor—not just to treat the sick, but also to comfort them. “I would take their hand while they were speaking to me, and everything changed,” she says. “They held on tight, almost a reflexive action, like babies do.”

Calderone returned to Turin in June, after the first wave ended; today she works in a local facility that was once a nursing home but was converted to a COVID-19 hospital when the disease crested again this autumn. “This second wave is even more difficult than the first,” she says. “There is much more exhaustion.” Still, she says, she has no regrets. “When I wake up and open my eyes, I know I have a role.”

Archana Ghugare faces not just fatigue but also economic hardship as a result of her commitment to battling the virus. A 41-year-old community health worker in India’s western state of Maharashtra, she is part of a 1 million-strong all-female force known as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs)—workers serving as a conduit between rural communities and the broader public-health system. She worked five to six hours a day as an ASHA before the pandemic. When the disease first hit, that stretched to 12 hours—and required that she sacrifice more than time. The government paid a monthly COVID-19 bonus of just 1,000 rupees, or about $13.50—enough for two weeks of groceries for Ghugare’s family of four—which did not make up for what she had been earning from other part-time jobs, or her husband’s income when he lost his job as well.

“It feels like there is a sword over our heads,” Ghugare says. Things improved in October when the COVID-19 caseload began to fall and she could return to her part-time work. But with the recent November spike in infections, the government has asked the ASHAs to be on standby, likely putting Ghugare back in the fight. “We are told we have the respect of millions around the country for the work we do,” she says. “But respect won’t fill our stomachs.”

If the pandemic has spared no part of the world and no portion of the population, it has nonetheless exhibited a special animus for the elderly and the housebound. That has pressed a whole population of workers into emergency service. Tanya Lynne Robinson, 56, is a home health aide in Cleveland, caring for people too old or sickly to venture outside—and thus performing her service in near invisibility.

“We do our job every day without people saying thank you,” she says. “We’re the forgotten heroes, the underpaid heroes.” Early in the pandemic they were also the underprotected heroes. The agency that employs Robinson had only limited PPE for its workers, and in her case that was especially dangerous. Suffering from asthma and multiple sclerosis, she is at risk of contracting a severe case of COVID-19.

All the same, even before the third wave of the pandemic hit, she redoubled her commitment to battling it. In September, she became state-tested nursing assistant and is planning to take online courses to become a licensed practical nurse as well. “I’m prepared to do whatever I need to do,” she says.

Home health aides like Robinson have not been alone in receiving too little recognition. Take Sabrina Hopps, 47, a housekeeping supervisor who works 10½ hours a day in a Washington, D.C., intensive-care unit, sanitizing patients’ rooms. It is Hopps and workers like her who disinfect light switches, bed rails, call buttons, side tables and ventilator machines. It is Hopps and others like her who, because of U.S. health-insurance privacy requirements, may not even know if a patient whose room they are cleaning has COVID-19. And it is Hopps and those like her who have become among the patients’ few human contacts. “Just having a conversation with a patient, that will make their day better, on top of yours,” she says. And as for those patients on ventilators who can’t talk at all? “I have learned to read lips,” she says.

Then too there is the staff of the SharonBrooke assisted-living facility in Licking County, Ohio, who not only tend to their elderly patients but also moved in with them for 65 days early in the pandemic and 30 more later in the summer. The reason: if they all quarantined together, they could minimize the chance a staffer could contract the virus on the outside and transmit it to the vulnerable population within.

It wasn’t easy. The staff showered in shifts, did their laundry only on assigned days, and gave up the simple privilege of sleeping in their own beds and seeing their families. “It was kind of like we were in college again,” Amy Twyman, the assisted-living facility’s executive director, says. The result of the voluntary quarantine? As of this writing, there have been more than 350,000 COVID-19 cases and 72,000 deaths in U.S. nursing homes—but not a single SharonBrooke resident or active employee has contracted the virus.

Concerns that schools, like nursing homes, would become viral danger zones left the country’s more than 13,000 school districts scrambling to figure out all manner of home and hybrid learning systems on the fly. That has posed special challenges for school nurses like Shelah McMillan, 46, who works at the Rudolph Blankenburg School in Philadelphia, as well as in the emergency room of the city’s Einstein Medical Center. With her school district having gone to fully remote learning, McMillan worries that a vital piece of the children’s medical care is going missing.

“We bridge the gap between the medical community and the families,” she says. “When you’re in the building, you get to see your children and you get to know your frequent fliers, and you get to hug your babies. Now you can’t see them, and it’s harder to track.” Still, tracking her babies she is, creating a phone number to field calls and texts from parents, and answering questions about the pandemic and individual students’ health. When she doesn’t hear from parents, she reaches out on her own.

Since the spring, McMillan has also worked with the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, which provides free testing in African-American communities in Philadelphia that have been hardest hit by the virus. According to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention figures from Nov. 30, Black Americans are at 1.4 times greater risk of contracting COVID-19 than white non-Hispanics; among Hispanic communities, the risk is 1.7 times greater. Both groups are at 2.8 times greater risk of death from the disease than white people. Income disparities and lack of access to health care facilities and insurance are all drivers of the inequality. McMillan and others have been doing what they can to bring health—and equity—to these communities.

For all the frontline workers have done to protect and serve, too many of them have been feeling increasingly underappreciated. Jim Gentile, 64, a surgical-services nurse at St. Mary Medical Center in Langhorne, Pa., is part of a staff that has seen its patient count explode during pandemic peaks. Gentile considers the ideal patient-to-nurse ratio 3 to 1, but in recent months that has often spiked to 6 or 7 to 1.

“It was taxing physically to say the very least, and it was emotionally taxing because they were dying right and left. I wrapped more bodies in two months than I did in 25 years,” Gentile says of the spring. “You have to steel yourself. You fall apart on your way home in the car. You fall apart in the shower. And 12 hours later, you’re back in the show again.”

For the nursing staff, that pace was sustainable only for so long. During a COVID-19 lull in the summer, they reupped previous requests for hospital administrators to bring on as many as 50 more nurses to meet the anticipated fall surge. The two sides were at an impasse for weeks and then months, with the nurses even going on strike for two days, starting Nov. 17. They still have not come to terms, and the nurses continue to plead with management as they watch their wards fill up with COVID-19 patients. “This time I think we all have a little PTSD,” says Gentile, “but we’re laser focused.”

Elsewhere, health workers are feeling not just a lack of appreciation, but open hostility. In the U.S., Fauci and others who have warned of the dangers of the virus and the importance of social distancing have been falsely accused of scare-mongering and even exaggerating the pandemic to turn the public against the Trump Administration in the run-up to last month’s election. Calderone, the doctor in Turin, recalls the first wave of the pandemic when physicians were cheered as heroes, with songs from balconies and pizza delivered to their wards. No more. “Some people think that we are the ones who exaggerate, and therefore the cause of the restrictions,” she says. “It hurts and upsets me.”

In Russia, frontline health workers are battling the rancor and mistrust of not just the public, but also the government. In the spring, the government insisted that the country had few cases relative to its geographical neighbors, and promised to provide doctors “high-quality and effective protection.” Anastasia Vasilieva, 36, the head of Alliance of Doctors, an independent medical trade union, has traveled to 11 hospitals in Russia, video-taping the poor working conditions and posting evidence of their government’s misleading claims on the alliance’s website. “Chief doctors force medical workers to treat patients without wearing PPE,” Vasilieva says, “and forbid them from speaking out if they have symptoms of the virus. I want to cry sometimes when I see what conditions medical workers are used to.”

The government branded Vasilieva a liar, and on April 2, the police beat and detained her overnight while she was trying to deliver PPE to a hospital in a small town north of Moscow. Since then, the police have continually shown up at hospitals the alliance has tried to enter, sometimes detaining members and pushing them forcibly away. Vasilieva insists she will not relent. “If the government wants to harm me, they will,” she says. “I’m not afraid.”

Inevitably a pandemic becomes a matter of social justice, as it has in America’s Black and Latinx communities, with marginalized groups suffering the most. In the U.S., this is especially evident in Native American communities, where risk for both infection and hospitalization is higher than among any other group in the country. Early in the pandemic, when the disease had not yet spread throughout the U.S., Pete Sands—musician, activist and member of the Navajo Nation—was working in the communications department of the Utah Navajo Health System when, as he told TIME in May, he was talking with the clinic’s board members. “There was just something that kind of spoke inside all of us saying, ‘This is going to come here.’” By May, the Navajo Nation had surpassed New York for the highest case rate in the country. Sands and the clinic established pop-up testing sites and—in collaboration with the Mormon church, the Utah Trucking Association, the produce company SunTerra and others—provided food and firewood through deliveries to rural residents and curbside pickups, where cars lined up for miles as residents waited their turns.

As caseloads dipped during the summer, Sands saw trouble coming. “People are gonna feel like we’re over this,” he recalls thinking. “They’re gonna start traveling; tourists are gonna come to the reservation.” And they did, but Sands and his team have kept at it, continuing their work as case counts have climbed again, and extending aid to Native American groups in Arizona and New Mexico.

The plague will eventually end. The suffering will stop. The dying will stop. There will be scars—lost family members, broken households, the post-traumatic pain of health workers who held too many dying hands, wrapped too many lifeless bodies. But the world will come through to the other side of the crisis—and in some ways already has. It was China in which the virus emerged, and it is China where it has been most effectively brought under control.

Liu Chun, 48, a respiratory doctor specializing in ICU patients in Changsha, a city in central China, was one of the first to volunteer to travel to Wuhan when the virus broke out there—part of a group of 130 doctors from her hospital alone. Some of them wept in fear as they set out for Wuhan; one of them scribbled out his will. “I was a little nervous,” Liu concedes. “We began to call [the virus] ‘the silent killer.’”

The killer has stopped killing in most of China, and the coming vaccines should finally end it all but completely there—and everywhere else too. The memory of the horror will remain, and of the heroism too. In the face of a pandemic that dared humanity to show its best, its bravest, its most selfless selves, the frontline workers delivered. —With reporting by Abigail Abrams, Jamie Ducharme, Tara Law, Katie Reilly and Francesca Trianni/New York; Francesca Berardi/Turin; Charlie Campbell/Changsha; Abhishyant Kidangoor/Hong Kong; Madeline Roache/London; and Abby Vesoulis/Washington

Dr. Anthony Fauci

Most 79-year-olds don’t get unsolicited phone calls about brand-new job opportunities. But few people of any age have Dr. Anthony Fauci’s résumé, or stamina. When Joe Biden called Fauci on Dec. 3 for their first conversation since the election, the President-elect asked him to stay on as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a position he’s held for 36 years—and to serve as chief medical adviser to the new Administration. “I said, ‘Mr. President-elect, of course I will do that; are you kidding me?’” Fauci recalls a day later in an interview with TIME.

And true to form, Fauci, who has guided the U.S. through HIV, H1N1, SARS, MERS, Ebola and Zika, was immediately on the job. During the 15-minute call, Biden solicited Fauci’s advice about what has become a point of contention between public-health experts and the outgoing Trump Administration: the role of masks in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. Biden said once he was inaugurated, he planned to announce a 100-day nationwide mask-wearing policy, as a way to tamp down the rising wave of coronavirus cases. It’s something Fauci has urged but President Trump never supported. Fauci agreed with the idea, as well as Biden’s proposal for limited mask mandates, starting with those who work on and use public transportation like buses, trains and subways.

“He is one of the most universally admired infectious-disease experts in the world,” Dr. Howard Koh, a professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and former Assistant Secretary for Health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, says of Fauci. “For the health of our country and the world right now, he needs to be front and center every day.”

That might seem like a given during such a public-health crisis, but over the past year, experts like Fauci were forced to battle not just a new virus but also a President who assaulted scientific facts for political gain. Week after week, as Donald Trump commandeered pandemic press briefings and turned to social media, first to downplay the extent of the disease and paint a rosier-than-reality picture of the U.S. response, and then to espouse unproven or even dangerous “treatments,” the voices of public-health experts became harder to hear.

Throughout those weeks, Fauci took every opportunity to keep those voices from going silent, even as his own was turning raspier from his constant media appearances, press briefings and private meetings with Administration health officials. The world watched as Fauci conducted a master class in scientific diplomacy, witnessing in real time how his understanding about the virus changed as science tried to keep up with the pandemic, and how he deftly adjusted and refined public-health messages as that knowledge grew. We watched as Fauci held live demonstrations on how to stay true to the facts in the face of those who seek to undermine them.

In July, after Trump touted hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment, Fauci noted that no rigorous studies showed the malaria drug was effective against the virus. During a Senate hearing in September, Fauci strongly disagreed with Senator Rand Paul’s suggestion that natural herd immunity—achieved by allowing the virus to infect a population so more people can develop immunity—was a reasonable solution to the pandemic. Most U.S. public-health experts never entertained this as a viable pandemic-control strategy because it’s too risky for people’s health. “You’ve misconstrued that, Senator, and you’ve done that repeatedly in the past,” Fauci said.

He saved his strongest rebuke for a Trump re-election campaign ad, which took something Fauci had said about the work of the coronavirus task force on which he serves to imply that Fauci approved of Trump’s pandemic response. Fauci immediately countered the idea that he would endorse any political candidate, and said the quotes were taken out of context. “I really got pissed off because I am so meticulous about not getting involved in favoring any political group or person or being part of any kind of political thing,” he says.

As he continued to defend the facts and just the facts, Fauci became a household name. Today, he is both a symbol of scientific integrity and a target of frustration, criticism and even violent threats by those who blame him for the school closures, job losses and deaths of loved ones from COVID-19. But he is keenly aware that both the hero worship and the scapegoating are a consequence of his becoming a stand-in for the complex fallout of the pandemic. He has continued to oversee the basic research that has now led to an approved drug and two COVID-19 vaccines that could start being distributed to the public by Christmas.

And he doesn’t plan on stepping down anytime soon. “I’m not even thinking of walking away from this,” Fauci says. “You train as an infectious-disease person and you’re involved in public health like I am, if there is one challenge in your life you cannot walk away from, it is the most impactful pandemic in the last 102 years.” —With reporting by Madeline Roache/London

This article is part of TIME’s 2020 Person of the Year issue. Read more and sign up for the Inside TIME newsletter to be among the first to see our cover every week.

Buy a print of TIME’s Anthony Fauci and Frontline Health Workers Guardians of the Year covers

Correction, Dec. 11: The original version of this story misstated Tanya Lynne Robinson’s title. She is a state-tested nursing assistant, not a certified nurse’s aide.

Correction, Jan. 4: The original version of this story misstated where Dr. Rebecca Martin is from. She is from Mountain Home, Ark., not Mountain Hope.

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com.