Detroit

The Art of the Comeback

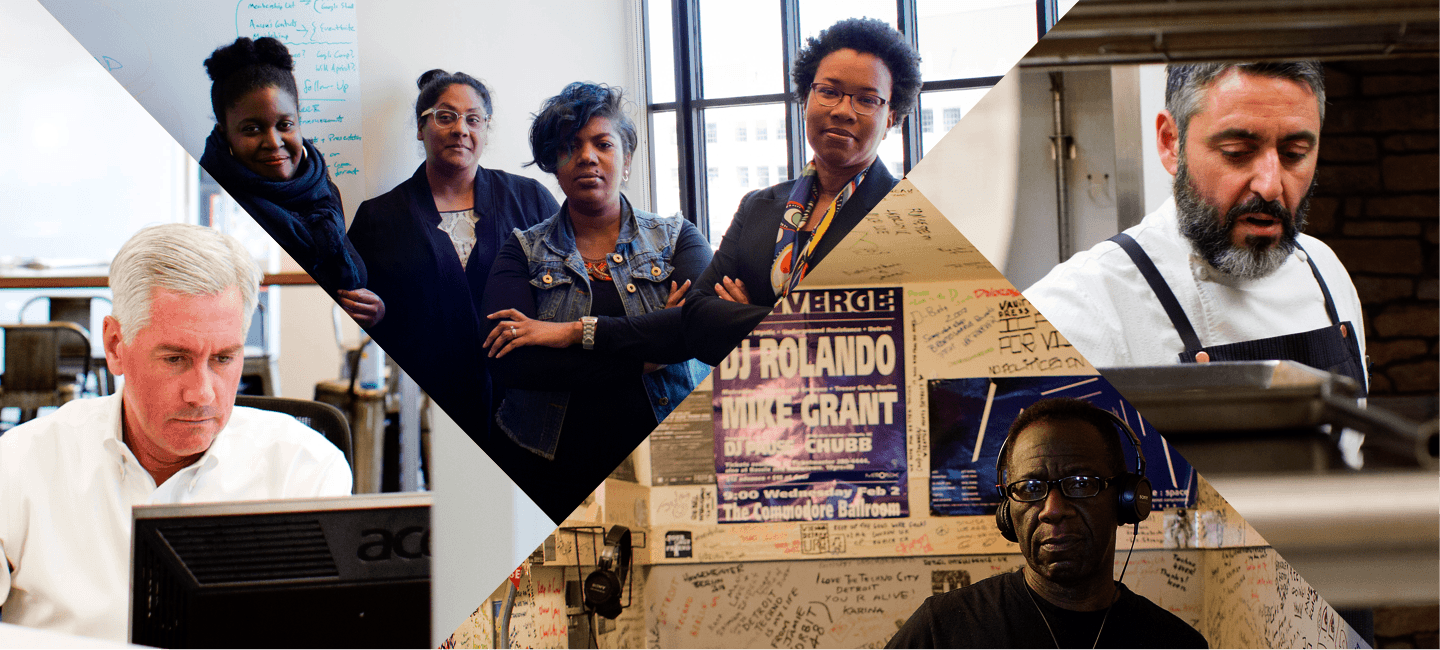

Detroit is a city becoming. Rich with history, full of tradition and still driving—always driving—toward the future, Detroit today is not the Detroit of yesterday, nor is it the Detroit of tomorrow. It is the Detroit of right-this-very-moment. We asked four community leaders to chronicle their city, their heroes and the vibrant life within the 313.

PROFILE ONE

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

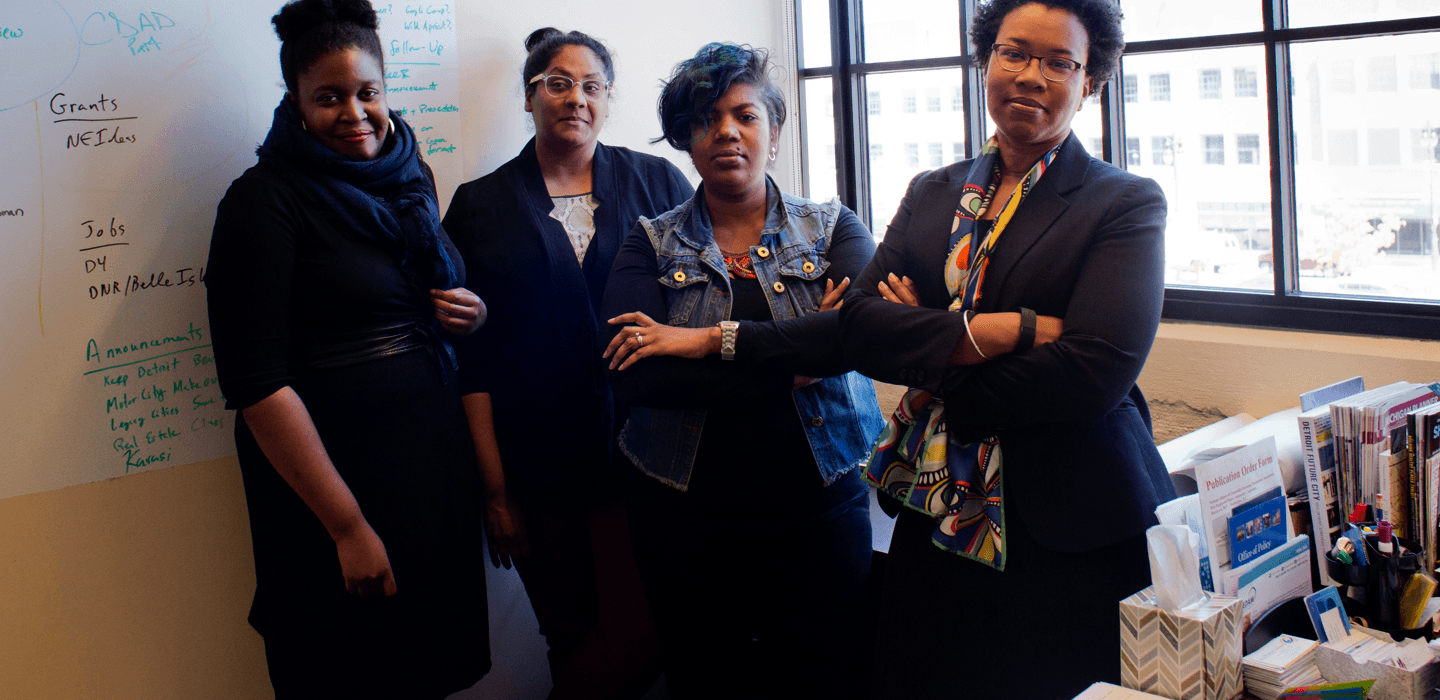

Erica Raleigh, executive director of Data Driven Detroit, on Sarida Scott, Quincy Jones and the power of data to transform neighborhoods.

For decades, Detroit has struggled. It is known internationally as one of the most challenged cities in the U.S. Some write us off, others wonder why anyone still lives here—why anyone even bothers trying to turn things around. And yet Detroit not only persists but flourishes. We hustle harder, with a DIY mentality that doesn’t quit. It’s a beautiful and resounding part of our culture. But sometimes community development can feel disjointed and fragmented.

Our mission at Data Driven Detroit can help knit these efforts together. At D3, we’ve created a central repository for data where community advocates can go to find the information they need to make good decisions for their community. If, for instance, you’re looking to fund investments in early-childhood education, it’s important to know where children are actually living so that you can direct your resources accordingly. When we started in 2009, we knew it wouldn’t be easy. Data was scattered everywhere, locked up inside individual organizations and municipal departments, becoming part of the scar tissue that had developed over years of disjointed redevelopment. We had a long, uphill battle to build the trusting relationships required to encourage people to share their data with us.

One of the visionaries who saw early on the potential of using data to make life better was Sarida Scott, a passionate community organizer, Detroit resident and the executive director of the Community Development Advocates of Detroit (CDAD). Back in 2011, CDAD partnered with D3 to develop the Neighborhood Revitalization Strategic Framework, which provides a vision for the potential future direction of any given area in Detroit, including areas that are underutilized or abandoned. The framework involves a community-driven, neighborhood-focused planning process, driven by the data previously collected, but seldom made accessible, to the community.

Sarida and her team at CDAD work with hundreds of local organizations across Detroit’s seven city council districts. One of them is Osborn Neighborhood Association (ONA), in the northeast part of the city. ONA is led by executive director Quincy Jones, who grew up in Osborn and eventually went to Mali with the Peace Corps. At home he worked at companies like Coca-Cola and earned his MBA at Lawrence Tech. With ONA, Jones is helping to transform the blight of Osborn. At the heart of the revitalization project is his commitment to bringing civic life back to the neighborhood. Whether this takes the form of offering midnight boxing clinics at the Matrix House, a bustling community center, circulating a neighborhood newsletter or incentivizing community involvement by offering housing at discounted rates for active members, ONA’s programs begin at the local, very human level.

Driving the change is not just data but a community of people devoted to that change. This community includes Sarida and her team at CDAD. It includes us at Data Driven Detroit. It includes hundreds of other like-minded organizations. As motivated Detroiters, we are weaving a new future for our city, turning DIY into DIT: do it together.

Erica Raleigh, who grew up just outside of Detroit, is the executive director of Data Driven Detroit. Founded in 2008, D3’s mission is to provide accessible, high-quality information and analysis that drives informed decisionmaking throughout Detroit. Raleigh earned a master’s degree in urban planning from Wayne State University and has been with D3 since 2009.

Contributor Photo by Laura McDermott.

PROFILE TWO

ENTREPRENEURIAL SPIRIT

Ned Staebler of Detroit’s incubator TechTown on entrepreneur Dave Stenson and the new engine of Motor City.

To step into the onetime Chevrolet Creative Services Building—birthplace of the Corvette—designed by renowned architect Albert Kahn, is to enter a sunlit buzz of ideas and activity. This is TechTown, Detroit’s most established business incubator and accelerator, full of really smart people getting things done. And not just any things. Things that matter.

One of those people is Dave Stenson. Dave came to us in 2013 with a new company and an intent to hybridize medium-duty work trucks. What Dave and his company, Inventev, are doing is developing a system that will enable a commercial fleet truck—think the repair truck you see working on power lines—to not only run but also operate its accessories using electricity. This “Energy SWAT Truck” will also serve as a mobile generator, providing backup power in areas hit by natural disasters and in the developing world. Dave’s patented system could even save lives.

TechTown has worked with Dave to develop business-growth strategies, protect his intellectual property and connect with funders, the media and even the White House, where he recently attended a briefing on energy policy and climate change. Meanwhile, NextEnergy, a center promoting advanced energy technologies that, quite deliberately, is across the street from us, has provided technical and additional commercial support and will soon serve as the test site for Dave’s first prototype. This collaborative spirit is in Detroit’s DNA. There’s healthy competition, sure, but it’s standard practice for organizations to work together to support our entrepreneurs and for entrepreneurs to champion one another.

Dave took the jump into entrepreneurship after 30 years at General Motors. He is a typical TechTown entrepreneur, which is to say he’s not typical at all. A sizable number of our entrepreneurs are nonwhite, women and/or over the age of 50—a reflection of our community—and their stories are as varied as their ideas. The one thing they have in common is a desire to use their ingenuity to make Detroit and the world a better place. Omer Kiyani is also an auto-industry veteran; he launched a biometric gun lock, Identilock, in January at the Consumer Electronics Show. Carla Walker-Miller started an energy firm, Walker-Miller Energy, after nearly 20 years at Westinghouse Electric and ABB. One of the few African-American female CEOs in her field, Carla recently secured a contract with the city of Detroit to provide LED lighting along major thoroughfares. Justine Sheu, who is in her 20s, parlayed her work as a college counselor for Detroit students into Pro:Up, an app linking high school students to internship and mentorship opportunities.

And that’s just tech. A few years ago, we realized that the incubation and acceleration strategies we were using to support our tech businesses could help drive a resurgence in Detroit’s neglected commercial corridors. So we’re working with small-business owners to launch, stabilize and grow their enterprises in neighborhoods across Detroit. Pages Bookshop in Grandmont Rosedale and Three Thirteen on East Jefferson are just two of the nearly 50 local retail establishments we’ve helped create and sustain.

The work we do at TechTown is not just about individual entrepreneurs. We are strengthening the economy of an entire city, region and state. Detroit’s struggles are legendary and oft-discussed. But the real story is our resiliency. The sense that we are on the brink of something monumental is palpable. Entrepreneurs like Dave and the many other game changers we work with remind me of this every day.

Ned Staebler, a graduate of the University of Detroit High School, Harvard University and the London School of Economics, is the president and CEO of TechTown. He also serves as the vice president of economic development for Wayne State University, from which TechTown developed in 2000.

Contributor Photo by Laura McDermott.

PROFILE THREE

CULINARY REBIRTH

Chef James Rigato of Mabel Gray on his mentor Luciano Del Signore and the deep roots and new bounty of Detroit’s dining scene.

The road map of Detroit’s future is outlined in its past. From Motown to Mopar, Eminem to GM, the city is a vast, varied and historic collection of paradoxical influences. The Italian immigrants who opened liquor stores, bakeries and restaurants are seeing the Chaldean community step in as the next wave of influence. Meatballs and gabagool are sharing the menu with dolma and shawarma. Midtown, downtown and Corktown are brimming with growth, and the conversation of food in and around Detroit is finding a place at the national table.

The last 17 years in the Detroit food scene have been an interesting and transitional time for my generation of chefs. Many great chefs have come and gone. But one chef has been cooking relevant, passionate and indigenous Michigan food since long before I was born and is still banging pans today: Luciano Del Signore.

Luc, as his friends call him, was the second-born son of John Del Signore, a restaurant owner and celebrated Italian man in the Detroit community, someone my grandfather John Rigato held in high regard. In the early 1990s, when I was a kid, we would eat at John Del Signore’s restaurant Fonte d’Amore. I remember the spiedini alla romano. It was Luciano’s spiedini, under the cloak of his father and brother. Luciano cooked under that cloak until 2003, when he went out on his own with Bacco.

Thirteen years later, with endless accolades (including James Beard nominations) and the addition of six restaurants to his empire, chef Luciano spends his free time mentoring me and my community of chef friends. He is a pillar in the Detroit food scene. He is the chef-owner model I follow, so much so that we whisper his nickname around town: the Godfather.

The restaurant boom that Detroit is experiencing doesn’t include the opening of fine-dining restaurants like Bacco. But chefs like Andy Hollyday at Selden Standard and Doug Hewitt at Chartreuse, not to mention Brad Greenhill at Katoi, all owe Luc a deep debt.

Not only has he been an inspiration, but he also continues to be a pillar of support. Some of the most exciting chefs around town, including Nikita Sanches of Rock City Eatery, Brendon Edwards of Standby, Nick Rodgers of the Root and Marc Bogoff of the food truck Stockyard, have all been showcased at Bacco as guest chefs. Detroit has a culinary bloodline that leads back to Luciano.

So here’s to Luciano, a man who embodies the opening lines of Detroit poet Robert Hayden’s poem “Those Winter Sundays”:

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

James Rigato is the owner and executive chef of the Root Restaurant and Bar, which was named Restaurant of the Year by the Detroit Free Press when it opened in 2012, and Mabel Gray, which opened in 2015 and was a semifinalist for the James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant. Both the Root and Mabel Gray focus on showcasing the bounty of Michigan ingredients.

Contributor Photo by Laura McDermott.

PROFILE FOUR

MUSIC SCENE

Carleton S. Gholz, executive director of the Detroit Sound Conservancy, on DJ John “Jammin’” Collins, a transformative figure in the local DJ scene.

As a teenager in the 1960s, the DJ John “Jammin’” Collins danced on the TV show Swingin’ Time, Detroit’s version of American Bandstand. "I met all these entertainers—Tina Turner, Aretha Franklin, Supremes, Temptations, Spinners, everybody,” Collins says. "They all came on the show. It was a lot of fun." Those TV-dancing days are long gone, along with Motown Records and even his home, demolished to make way for controversial urban-renewal projects in the 1960s and ’70s. But Collins is still here.

In 2011, in the midst of the economic crisis, Collins produced his first 12-inch record. The gospel-tinged house-techno hybrid “Yeah” went directly against the grain of the doomsday pronouncements of Detroit’s collapse. Now 61, Collins produces house and techno records for Underground Resistance and deejays in Detroit and around the world. He is a member of the Detroit Entertainment Commission and serves on the board of the Detroit-Berlin Connection—an attempt to more deeply connect two cities that have inspired each other musically and culturally for generations. Whether he is deejaying at an LGBT shelter or at Motor City Wine, a bar as open to house-music DJs as it is to jazz combos, Collins exemplifies the confidence and pride that comes with years of practice and a rich sense of musical history.

In Detroit, despite the atrophy of some small music venues, an overlapping network of clubs, talent and production crews continues to mix old and new traditions at the margins, reminding its audience that there is a continuity to the city’s brazen musical output. Promoter Steven Reaume, whose late-night after-hours parties are legendary, says it best: "Detroit is one scene. Promoters, DJs, artists all support each other, not compete against each other.”

Virginia Benson, a former bartender at Garden Bowl, one of the birthplaces of Detroit’s turn-of-the-century garage-rock scene, has taken what she has learned to become a critical promoter and talent buyer in the city. Her Party Store Productions now books talent like psych-punk band the Deadly Vipers at the Marble Bar, a venue hidden in plain sight in an old bank that only recently was a longtime Detroit leather bar. Benson also books shows at the UFO Factory, a Corktown hangout for Babe Ruth and Bobby Layne that was reborn in 2014 as an indie-rock club and art gallery. "I want everyone to feel comfortable going to a show or a dance party. I want it to be as diverse as possible, and open people up to new things,” she says.

That inclusive approach is best embodied by trumpeter Dameon Gabriel of the Gabriel Brass Band, which he leads with his cousin once removed and grand marshal, Larry Gabriel. Larry's cousin, Detroit-raised Charlie Gabriel, is a clarinetist for the touring version of New Orleans' Preservation Hall Jazz Band. The Detroit-based Gabriels, especially Dameon, have their hands full. He is building out Gabriel Hall, a new venue in the city’s West Village. There is a lot of work to be done on the boarded-up building, which has been abandoned since the 1990s. But Dameon, a fifth-generation musician, is optimistic about opening next year: "Now is the time. I have the opportunity to do it. And yes, Detroit is ready.”

Carleton S. Gholz is the executive director of the Detroit Sound Conservancy, whose mission is to increase awareness of and support for Detroit’s musical heritage through advocacy, preservation and education. Gholz, who was born in Port Huron, Mich., teaches the history of American music at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit. He is currently working on a book about the rise of DJ culture in Detroit.

Contributor Photo by CJ Benninger.