"Is there any practice less selfish, any labor less alienated, any time less wasted, than preparing something delicious and nourishing for people you love?" asks author Michael Pollan in his book Cooked, now a Netflix documentary series. Watch now on Netflix. The answer is, there isn't. For the last 50 years, TIME has tracked how this labor of love has evolved. Inspired by Pollan's insight, we dug into our archives to revisit how, why and for whom we cook.

America En Croute

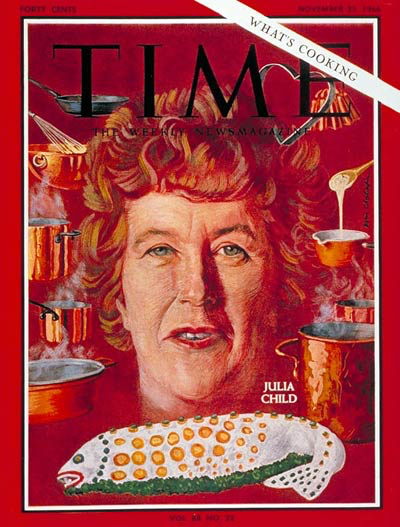

The 1960s were an era of seismic change in America. How we lived, how we loved, how we ate. One woman in particular, a housewife from Pasadena named Julia Child, revolutionized the kitchen. We still feel her influence today.

The 1960s were an era of seismic change in America. How we lived, how we loved, how we ate. One woman in particular, a housewife from Pasadena named Julia Child, revolutionized the kitchen. We still feel her influence today.

In 1966, TIME called Julia Child, “the most influential cooking teacher in the U.S.” In many ways, Child — who died in 2004 — still is. Her seminal 1961 cookbook Mastering the Art of French Cooking and subsequent TV show, The French Chef, demystified French cuisine. Her rise led to the ferment of food in popular culture we see today.

Child was one of America’s first true celebrity chefs, a phenomenon that has grown from a cottage industry into a multibillion dollar cultural juggernaut today. In 1966, TIME writer Ray Kennedy name-checked “a new hierarchy of gourmet cooking teachers,” chief among them Child, along with James Beard, Craig Claiborne, Dione Lucas and more. They published influential cookbooks, made TV appearances and wrote for top publications on matters of food and cooking.

These were not restaurant chefs sharing professional insights. Rather, this early wave of celebrity-chef figures were gastronomic enthusiasts hell-bent on getting home cooks comfortable with the act of, well, home cooking. From instructing people on how to shop for fresh, high-quality ingredients to encouraging the use of foreign ingredients to advice on specific tools and equipment, their goal was to get both men and women into the kitchen without feeling bored or afraid.

Today, both the role of celebrity chefs and our relationship with food (and food media) has changed dramatically. Publicly televised cooking shows like Beard’s and Child’s were focused squarely on teaching people how to cook, with gusto and without shortcuts. By 1993, cooking shows had proved popular enough to inspire the launch of a 24-hour cable TV channel called the Food Network, whose early programming included archived episodes of “The French Chef” and entertaining-yet-accessible culinary advice from up-and-coming chefs like Emeril Lagasse.

By the late '90s, the Food Network’s programming had split into two distinct blocks: “dump and stir” shows during the day, which typically featured friendly, female home-cook types who were at least somewhat concerned with teaching viewers how to cook food at home (though often, in contrast to Child’s MO, very quickly and very cheaply). At night, the instructional element was abandoned in favor of reality, competition and travel-centric shows, with on-screen talent more enthused about eating food than actually cooking it. This type of programming appeals to a wider audience (read: more men) than the instructional shows, and has spawned a great many imitators on other networks eager to cash in on the appeal of food content.

The reach of the celebrity chef has expanded, too. “Let Julia Child so much as mention vanilla wafers, and the shelves are empty overnight,” wrote Kennedy, while also noting the “avalanche” of new cookbooks at the time — “206 in the last year alone.” Those lines can be correctly read as a harbinger of the explosion in consumer interest in chef-related merchandise that would come in later years. Cookbooks alone raked in $228 million in revenue in 2014, and many high-profile chefs view them as marketing collateral, pumping out new titles yearly (a far cry from Child’s efforts with “Mastering,” which took seven years to complete and clocked in at 850 meticulously researched and tested pages). Celebrity chefs have taken merchandising a step beyond, too — in lieu of endorsing a specific brand of pans or spatulas, figures like Rachael Ray and Mario Batali have branded their own instead, teaming up with retail outlets like Macy’s and Walmart to reach customers.

Americans show little sign of slowing in their appetite for chef- and cooking-related goods: beyond the books and the merchandise, we’ve witnessed in the past 40 years the rise of food magazines like Bon Appétit and Food & Wine, which reinforce our vision of chefs as celebrity figures. The impact of food television has evolved beyond the confines of our screens and spawned multi-city, lavishly priced food festivals with appearances from onscreen talent and over-the-top parties.

It’s a long way from the world Julia Child inhabited in the 1960s, when she first introduced Americans to the pleasures of soufflés and coq au vin. We know more today than we ever have about the inner workings of food and kitchens, even if we spend less time than ever actually cooking. It’s a uniquely American contradiction, and one that illustrates how truly obsessed we are as a nation with all things food.

The Founding Foodies

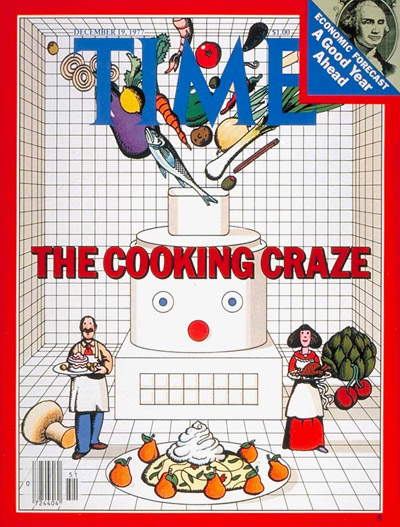

The 1970s marked the birth of the American foodie, a species common now. But in 1977, the foodie was still as rare as pâté on a dinner plate.

The 1970s marked the birth of the American foodie, a species common now. But in 1977, the Foodie was still as rare as paté on a dinner plate.

In the 1950s, few Americans knew what a food processor was. Steak and potatoes were the dominant forces on the tablescape, canned soups and powdered sauces were all the rage, and women were expected to feed families with efficiency, if not great finesse. Home cooking was, in short, a necessity — not a luxury.

That began to change in the 1960s and '70s, thanks, in part, to our increasing appetite for international travel, the advent of televised cooking shows (notably Julia Child’s The French Chef) and a growing feminist movement that helped open minds to the notion that men could be at home on the range, as it were.

By 1977, the trend was in such full force that TIME published a cover story by Michael Demarest tracking the rise of the “great American love affair in the kitchen.” The foodie movement was born, and that movement has continued unabated to this day.

"Gourmet cooking at home is a movement that has arrived,” declared Craig Claiborne, then the food editor at the New York Times. "No doubt about it," said chef Jacques Pépin: "American home cooks today are the best in the world outside France and China." How did we get there? In that most American of fashions: by spending “unbelievable sums” on our newfound habit.

“Supermarkets from coast to coast now stock such onetime exotica as game pâtés, Beluga caviar, imported mustards, goat and sheep cheese, leeks, shallots, scallions, bean curd, pea pods, bok choy, capers, curries, coriander and cornichons,” reported Demarest. Specialty shops flew in Arava melons from Israel, wild mushrooms from France and white truffles from Italy, and quickly sold out to the ravenous crowds of aspiring home Escoffiers.

At the same time, however, “born-again American cooks” were rediscovering the “glorious raw ingredients and inimitable provincial dishes of their own country. Newly appreciated ... are such home-grown marvels as Long Island duckling, Maine lobster, Maryland lump crabmeat, Chesapeake oysters, Gulf shrimp and pompano, Louisiana crawfish, California abalone and Columbia River salmon,” according to the article.

This tension is still evident today. While championing the use of local ingredients has become fashionable, there is simultaneously a captive audience for big-ticket luxury ingredients: Japanese bluefin tuna, Russian caviar, fine wines from France and Italy. For every op-ed about food miles and fuel costs, there is a love letter to edible luxuries from far away.

Whether prepared in a well-appointed home kitchen or served in a fine-dining restaurant, foodie culture has not proven immune from socioeconomic factors. Even as a culture of appreciation has cropped up for the locally sourced and sustainable, economic factors mean there is even less time to cook.

Such is the economic reality of a flat world, that even as far-flung delicacies are increasingly available, the time to prepare them is increasingly difficult to come by. According to the Brookings Institute, “families earning the median income now work about 3500 hours, on average, compared to 2800 hours in 1975.” And what time is spent at home, around food, is often spent glued to the television screen, watching the progeny of Julia Child wage head-to-head battle in adversarial food programming.

It is safe to assume this was not the foodie culture Demarest — or Child or Claiborne or any of the other early foodies — envisioned, a culture of panem et circenses. And, to be fair, it is only part of what foodie culture has become. Because watching someone cooking is different than cooking for oneself. At its heart, our gusto for cooking is about transforming the raw ingredients of the world to nourishment for those we love. And that love affair is still as strong as ever.

The Plate of the Union

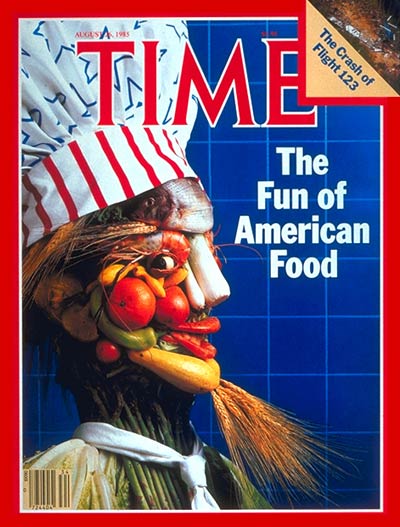

In 1985, New American cuisine was an emerging trend. Thirty years later, we look at how the style has evolved.

In 1985, Mimi Sheraton introduced TIME’s audience to New American cuisine, which she called “an intellectualized, even esoteric style, characterized by the use of fresh native products and seemingly disparate ethnic ingredients and influences in a single dish.” It was, she wrote, “the best melting pot tradition.”

At the time, the term was still malleable. “As far as I'm concerned, it is American food, cooked in America by Americans with American ingredients,” said Julia Child, who boasted of recently incorporating soy sauce and “an occasional chili pepper” into her repertoire. “The average diner is very much aware of 'new American cuisine,'” insisted Lydia Shire, then the chef at Seasons in Boston. ”It's out of the fad stage and is really the creative cooking of good simple food, using American products and infusing some kinds of classical preparations.”

Thirty years later, a precise definition of American cuisine is still hard to come by. Hotshot American chefs make dishes like brussels sprouts with fish sauce vinaigrette and escargot dumplings with bacon-tamarind sauce to great acclaim. Mainstream food magazines put Chinese five-spice-rubbed turkey on their Thanksgiving covers. “Ethnic” foods like hummus, once considered exotic, are part and parcel on supermarket shelves. And Americans have embraced eating out as an essential part of our social lives.

Many of the phenomena that Sheraton wrote about have become established practices today. In 1985, American ingredients were still rarely found at specialty stores. “Years ago, I carried Stilton, Roquefort, Gorgonzola and Danish blue cheeses,” said the vice president at Macy’s Marketplace in '85, “Now I stock about 15 blues, and two are American. I have 20 chèvres, four from the Northeast and two from the West,” he said.

Today, our domestic cheeses win international awards and independent producers are successfully making everything from microbrewed soy sauce to heritage-breed prosciutto on American soil. Some restaurants champion the use of heirloom ingredients indigenous to their region, while others refuse to use ingredients found outside of a small radius from their location.

But despite the occasional narrowed focus on ingredient sourcing, American cuisine has continued to defy easy boundaries. Chefs travel far and wide and borrow techniques and flavors liberally from around the world, with the results often appearing in the confines of a single bowl. They demure on the topic of labels, avoiding any attempt at categorization of their cuisine. This has been largely accepted by the media and the court of public opinion — at some point between Sheraton’s article and now, we stopped trying to lock down a definition. Now American cuisine is, in many ways, defined by its ambiguity, and justly celebrated for it.

Of course, not everything that reared its head in the emergence of the movement has lasted: “Several of the professional cooking schools have waiting lists for entry and report three to six available jobs for every graduate,” wrote Sheraton in 1985. Today, public opinion toward culinary school is ambiguous — magazines ask “Should You Go to Culinary School?,” graduates are filing class-action lawsuits against their schools, and Julia Child’s alma mater is closing all 16 of its U.S. locations.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the danger of overweening pride. Sheraton warned of “the hazard that the often exaggerated and premature praise they are getting will make them think they have nothing more to learn.” With the rise of celebrity-chef culture and the proliferation of hype-hungry food media, the concern that young cooks aren’t entering the industry with the humble desire to work hard and rise through the ranks is even more pronounced.

Still, Sheraton was prophetic. Today’s chefs are “no longer servants, but stars.” They are no longer bound by rules. Thirty years later, American food is still fun and getting funner, wilder and freer with each passing year.

America, Supersized

In 2002, writer J. Madeleine Nash declared, “As a society we are clearly in a state of nutritional crisis and in need of radical remedies.” But has anything changed?

With nearly 35% of adults in the U.S. tipping into obesity, Americans today are heavier than they’ve ever been. This trend is, unfortunately, nothing new. In 2002, in TIME’s cover story “Cracking the Fat Riddle,” writer J. Madeleine Nash declared, “As a society we are clearly in a state of nutritional crisis and in need of radical remedies.”

At the time, the low-carb Atkins diet was having its moment, in sharp contrast to the previous dietary fad, Dr. Dean Ornish’s low-fat method. At the same time, obesity numbers, Type 2 Diabetes and hypertension diagnoses were all on the rise. The central question that “fat riddle” posed was: Why are we so fat and what can we do to fix it?

Fourteen years later, we don’t have much in the way of answers. But it’s not for lack of trying.

Here are just some of the major cultural developments aimed at combating obesity in recent years: Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! campaign. Calorie counts on fast-food menus. A revised food pyramid — that’s actually a plate — with an increased emphasis on fruits and vegetables. Endless government debate over the possibility of a “soda tax.” Fast-casual restaurants that specialize in salad. Kraft’s removing artificial colors and preservatives from its iconic boxed macaroni and cheese. There has been an endless string of dietary trends too, less explicit in fighting obesity but still focused on the concepts of health and wellness: Juice cleanses. Superfoods. Raw foods. Whole grains. No grains. Gluten-free. The South Beach diet. The paleo diet. The macrobiotic diet. We know more today than we ever have before about how to be healthy. We have developed increasingly convenient and affordable ways to eat well. We know more, scientifically speaking, about why we’re fat. And yet ... we’re still fat.

In 2002, the scientific community had already concluded that there is indeed a genetic link to obesity — not that genes themselves are responsible for making us fat, but that some do make us susceptible to gaining weight under conditions that are particularly prevalent in modern American life. “In essence,” said Dr. Walter Willett of the Harvard School of Public Health, “sedentary lifestyles and a cornucopia of food have transformed people into the equivalent of corn-fed cattle confined in pens. We have created the great American feedlot.”

Today, we’re still exploring the role genetics play in obesity. Current studies suggest that some subset of obese people may have a biological imperative to hang on to extra calories. "While behavioral factors such as adherence to diet affect weight loss to an extent,” said Susanne Votruba, a clinical investigator at the Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch who released a study last year, “our study suggests we should consider a larger picture that includes individual physiology.”

What that means for the future of obesity prevention and treatment is still unclear. Beyond good old-fashioned diet and exercise, precision medicine — a highly personalized approach based on an individual’s biology — may be one answer. But scaling is difficult with such tailored treatment. Virtual reality, far-fetched as it may seem, is another possibility, with developers working on technology that allows users to “taste” food they’re not actually eating. The question now, as it was in 2002, is whether any of these new concepts “can restore sanity to a collective eating binge that has spiraled out of control.”

And so the answer to the "fat riddle" remains as hard to pin down now as it was in 2002. We must not change our eating habits. We must change ourselves.