Award-winning photographer Matt Black has spent the past four years traveling the country to document impoverished communities for his project, “The Geography of Poverty.” These previously unpublished photographs, taken between December 2016 and September 2017, along with diary entries from Black’s travels and an essay from the social entrepreneur Wes Moore, offer a stark portrait of the nation’s deepening inequality and division.

America, Out In the Cold

by Wes Moore

On the day the Dow Jones industrial average closed above 25,000 points for the first time in history, a video was going viral online. Filmed the day prior, Jan. 3, it showed an elementary-school teacher in Baltimore, former NFL player Aaron Maybin, sitting with his students. The young kids sat before Maybin on the floor in their dimly lit classroom, all bundled up in coats.

Population: 29,450

35.5% live below the poverty level

“What’s the day been like for you guys today?” Maybin asked them.

“COLD,” they said in unison. One child elaborated: “Very, very, very, very, very cold.”

The same day that this country celebrated an unprecedented moment of prosperity, schoolteachers in this same country were bringing in space heaters (and raising money to buy more) to try to warm up their freezing classrooms.

Population: 3,183

42.2% live below the poverty level

Population: 205,764

24.1% live below the poverty level

Population: 3,183

42.2% live below the poverty level

Population: 3,183

42.2% live below the poverty level

Elmer Smith, 54, lives in Montgomery, Alabama. “Another form of control, oppression, or separation: ‘You can’t vote. You can’t vote because you’re on drugs. You can’t pull away from that crack pipe long enough to go down there and vote. So, we got you.’ I just don’t think we are going to see it in our lifetime to where that dream is truly fulfilled.”

This isn’t an isolated trend. Far too many Americans are out in the cold.

People in poverty in America in 2018 are not a world apart—they are all around us, and their lives unfold next to, but are cut out from, any prosperity that this nation experiences.

Population: 584

41.3% live below the poverty level

It’s an injustice that is compounded 40 million times over—in the life and the plight of every American living in poverty at this moment.

Saturday, December 17, 2016. Timber Lake, SD

Negative 22 degrees at 10:00 AM. Following the Big Foot Memorial Ride from Timber Lake to Eagle Butte. As we move from reservation to reservation -— currently on the Cheyenne River Reservation — others are joining the original six riders. The horses are covered in ice by the end of the day’s ride: one black horse looks half white, covered from face to shoulders in clinging ice. The riders come in with ice crystals clinging to their eyes, eyebrows, and mustaches, looking as if they are coming from another planet. The landscape is a world of ice.

The real greatness of this country has always lived in its promise—that anyone, no matter their circumstances at birth or their current realities, should have the same fundamental right to opportunity and to liberty. In the imperfect trajectory of our nation, we’ve been at our greatest when we’ve empowered our citizens with that promise. On our winding path to progress, that promise has served as a critical guidepost. That promise is so fundamental to what it means to be an American that millions of my fellow veterans have fought and died to defend it.

The promise of America says that if you work hard—if you sacrifice—you, or at least your children, will succeed. But too many Americans today are sacrificing into an empty void, with no returns for generations. At a certain point, it’s not sacrifice anymore—it’s just suffering.

Population: 335,709

21.8% live below the poverty level

Population: 60,512

28.8% live below the poverty level

The Trump administration has placed Haitians in the U.S. under temporary protected status, or TPS, to begin to “prepare for and arrange their departure.” An immigrant from Haiti at home in Homestead, Florida, who requested anonymity for fear of legal repercussions, said, “If I go back to Haiti, I die.”

In this era of the American story, opportunity has never been more out of reach for so many. It’s never been more expensive to go to college. It’s never been more difficult to run a small business. It’s never been harder to earn a living wage. It’s never been easy to be poor, but I don’t think it’s ever been this complicated.

Population: 136,286

26.5% live below the poverty level

Though so many Americans live below the poverty line, many millions more live hovering barely above it—one layoff, one cancer diagnosis, one missed bus or train, one sick child, one shock away from falling into poverty. Many Americans who once made up the lower-middle class now find themselves the working poor.

Population: 212,237

30.9% live below the poverty level

Population: 186

35% live below the poverty level

For far too long, our nation has neglected its most vulnerable citizens. Far too often, these vulnerable Americans have been lied about and lied to.

We’re told people in poverty somehow deserve it.

Thursday, February 9, 2017. Hannibal, MO

Mark Twain’s hometown. Drove through New London, Frankford, Bowling Green, Clarksville, Annanda, Foley, Winfield, Old Monroe, ending in Ferguson, on the outskirts of St Louis. Went to the place where Michael Brown was killed: a peaceful, almost suburban street touched in a painterly way with yellow. A yellow car passes a yellow fire hydrant across the street from the beige-yellow apartments surrounded by yellowed grass.

We’re lied to about how quickly and how drastically our industries are changing, and how people are being left behind. We’re told people in poverty should just “get a job.” We’re told poor people in America’s heartland should blame poor immigrants in America’s border states for their poverty.

The pain of our most vulnerable citizens has been turned into political cannon fodder.

The reality is that the majority of people in poverty who can work are working and are still unable to earn a living wage. The reality is that too many people currently living in poverty were born there. The most shameful reality is that if someone grows up in poverty in America in 2018, they are more likely than ever to die in poverty.

Population: 3,505

22.6% live below the poverty level

People facing poverty in the U.S. look like all of us, and they live all around us. If the 40 million Americans in poverty have one common characteristic, it’s vulnerability. If they have one common virtue, it’s resilience.

They’re single moms working three jobs just to stay afloat, just as my mother did in the Bronx 30 years ago.

They’re displaced workers who went to work every day for 30 years, only to learn their jobs have been replaced by machines.

Sunday, February 12, 2017. Mankato, MN

From Mankato, MN, heading south and into Iowa, to the towns of Kensett, Rudd, Bristow, Dumont, Whitten, Belle Plaine, Blairstown and then Cedar Rapids. Churches and bagel shops. Poems written on the sidewalk. Mankato is the site of the largest execution in US history — 39 Dakota men hanged on December 26, 1862. Behind the coffee shops and art boutiques in Mankato, I encounter a man digging through dumpster for cans and bottles to recycle. He tells me, “When I have the gas for it, I walk about 30 miles in a day. I get about $15 on average.”

They’re people returning from prison with no path forward, beyond a criminal-justice system so broken that every sentence carries a life term, and finding they are barred from living in public housing or receiving financial aid for college.

They’re Americans suffering in Puerto Rico, a part of this country where the rate of poverty was nearly 45% even before a hurricane destroyed the island.

They’re children riding the bus home to empty pantries and fragile support systems.

They’re proud Native Americans in our heartland, living on reservations that have been chronically neglected.

Population: 740

20.1% live below the poverty level

Rather than invest in our most vulnerable Americans, rather than give their incredible, beautiful resilience something to latch on to, at best, we’ve neglected and ignored them. At worst, we’ve implemented policies that have put them in poverty and kept them there, and then buttressed and defended those policies with disparaging rhetoric.

Poverty is an injustice; no one deserves to be in poverty. And we can’t allow the promise of this country to become a myth.

The greatness of this America doesn’t belong to any single politician to give or take away. The greatness of America lives in its promise. That promise belongs to all of us, and it’s all of ours to defend and bring to bear.

Population: 12,865

29.2% live below the poverty level

Population: 22,194

25.2% live below the poverty level

Population: 3,505

22.6% live below the poverty level

Population: 4,134

22.0% live below the poverty level

Gloria Dickerson lives in Sunflower County, Mississippi. “Dr. King said in one of his last speeches that he had been to the mountaintop and he had seen the promised land. I don't know what he saw, but this is not it. Back in Drew…up Sunflower County, this is definitely not the promised land.”

Behind the Story

by Eben Shapiro

At 18, Matt Black had one of his first photographs published, in the Tulare Advance Register, the daily paper in the central California town near where he grew up. The black and white image was of activist Cesar Chavez breaking a 36-day fast designed to call attention to the use of harmful pesticides on grapes picked by migrant workers. The paper did not assign a reporter to the event, so the only coverage was the teenager’s photo. “That was a fundamental instruction on the power of photography,” says Black.

Population: 5,301

27.8% live below the poverty level

Population: 26

44.4% live below the poverty level

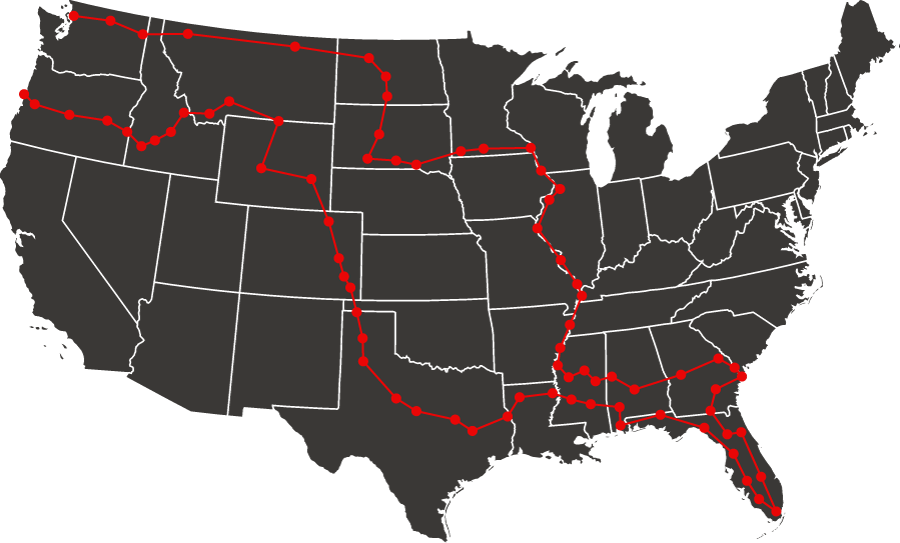

Now 47, Black, who still works in black and white, is one of the most respected documentary photographers of his generation. He is affiliated with the elite Magnum Photo agency and regularly receives grants and awards. Black’s concerns have remained largely the same: migration, agriculture and economic inequality. He is currently immersed in photographing census-designated “poverty areas,” communities whose poverty rates are in excess of 20%. Since 2014, Black has taken four separate cross-country trips, visiting 46 states, covering 88,000 miles. One leg, from Calexico, Ca., to Bangor, Maine, he took by Greyhound bus, getting off at regular intervals to shoot his stark, poetic images in towns along the way.

Population: 1,318

51.5% live below the poverty level

The rest of the trips he made in his 2014 gray aptly-named Honda Odyssey minivan. In total, he was away from home for 16 months and he’s about to hit the road again, to do follow-up trips to areas that particularly moved him on his travels.

Population: 4,153

35.7% live below the poverty level

Population: 2,801

39.5% live below the poverty level

Population: 319

71.6% live below the poverty level

Willis Hayes, a resident of Cherry Creek, in Ziebach County, South Dakota. “People think that Cherry Creek is a bad place, but that was a long time ago. Me and all my brothers, now, we're all grown up. We believe in our culture.”

Next month, he is returning to the southwest corner of Georgia, to document a thriving black farming community that is under threat from what Black calls “some pretty underhanded and vicious ways of separating people from their land.” He adds, “The pins are being kicked out from so many people.”

Population: 12,865

29.2% live below the poverty level

Black’s current project grew out of his work documenting extreme poverty in the Central Valley of California. The area once produced a lot of cotton (Black’s father was an engineer who worked on big irrigation projects) and is now dominated by citrus and grapes.

Sunday, August 13, 2017. Laramie, WY

The wide vistas of the Wind River Reservation do not connote grandeur but desolation. Like the name Wind River, there’s a force in the air, but it feels malevolent. The emptiness of the Wyoming plains is oceanic in depth. Boiling clouds of a thunderstorm pass overhead. A single-wide trailer encircled by a single-strand barbed wire fence sits broken-backed on its crumbling foundation. Lopsided reservation houses. Cars on cinder blocks in the yards, pop-up tents in the driveways.

Despite the agricultural bounty, more than 28% of the population of Tulare County lives below the poverty line. Taking pictures of the bleak local conditions spurred Black to launch a broader critique of income inequality across the country.

“So often, poverty is portrayed as if it’s some sort of strange anomaly,” says Black. “This project was an effort to counter that and show how widespread and ingrained it is in American life. You can find it in every state and every community.”

Population: 4,967

27.4% live below the poverty level

Population: 5,068

33.3% live below the poverty level

Earl Bryant, from Clay County, GA, says, “Well, it's never been great opportunity. Basically, as far as jobs go, you have to go other places to find a job. You see things, but you've got to look for joy, you've got to go on, you've got to look on the bright side of things.”

Roughly 40 million Americans, 12.7% of the population, live in poverty according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2016, about 18% of children (13.3 million) were living in poverty. A range of experts say the recently passed tax reform package will make income inequality worse.

Population: 2,497

39.3% live below the poverty level

A United Nations report on extreme poverty, published in December, concluded that the tax reform package is “essentially a bid to make the US the world champion of extreme inequality.”

Monday, September 11, 2017. Corning, CA

The sixteenth anniversary of September 11. Coming down I-5 on the west side of the Central Valley: tomato trucks whizzing to and fro. Arriving home today. I’m having the same sensation I have coming home by car — a strong sense of closeness to the rest of country, a knitted-ness that I wasn’t aware of before. It’s a sense of having traced the plotline backwards, from west to east and against history. From denouement to rising action. It’s raining, which is odd. In Firebaugh, I stop on the main street and see that the circus is coming next week. I go through Mendota, the second poorest town in California, and what was once agricultural fields are now vast solar farms.

Black says that “America is and has been in a state of denial about poverty in the country.” He adds, “It blows my mind that you can cross the country back and forth without ever having to leave these high-poverty communities.”

As he prepares to return to Georgia, Black brushes off questions about when the work will be shown in a museum or published in a book form. “Fundamentally, this work has turned into a questioning of some of the basic mythologies that we carry about America, that it’s a land of the opportunity, that the American dream is still viable. The question that the project asks is, ‘Is that still true?’”

Population: 6,188

28.7% live below the poverty level

Population: 319,294

27.1% live below the poverty level

“I was born and raised out here, and I've always liked to farm. You gotta like it to do it, under my category, no help, no kind of wages, barely getting by,” says Arthur James Baisden, who lives in Ty Ty, Georgia, population of 725, 33.3% OF whom live below the poverty line.

Statistics source: Population, 2010 U.S. Census; Poverty rate, 2015 American Community Survey estimate

Matt Black is from California’s Central Valley, an agricultural region in the heart of the state. His long-term work on poverty has been honored by the W. Eugene Smith Award in Humanistic Photography and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, among others. He is currently a Senior Fellow at the Emerson Collective and is represented by Magnum Photos.

Wes Moore is an author, a combat veteran, social entrepreneur and the CEO of Robin Hood, one of the largest anti-poverty organizations in the U.S.

Amy Pereira is an award-winning photography director, editor and visual storyteller. She has worked in partnership with Matt Black in publishing his seminal body of work, The Geography of Poverty, since 2015. Previously, she was the Director of Photography at MSNBC and longtime senior photo editor at Newsweek magazine.

Eben Shapiro is the deputy editor of TIME Magazine.

Kara Milstein, who helped produce this project, is an associate photo editor at TIME Magazine.

Kim Bubello, who helped produce this project, is a multimedia editor at TIME Magazine.