The irreversible damage of oil extraction to the earth’s ecology is already evident. But when plans for the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines were revived in the first days of the new administration, it became clear that America, the insatiable consumer, would not be turning green any time soon – one more chapter in a centuries-long battle over land and resources.

Here is a visual exploration of the environmental consequences of oil production – from the Alberta Tar Sands in northern Canada to the pipelines and refineries across America – as told through the work and words of nine photographers.

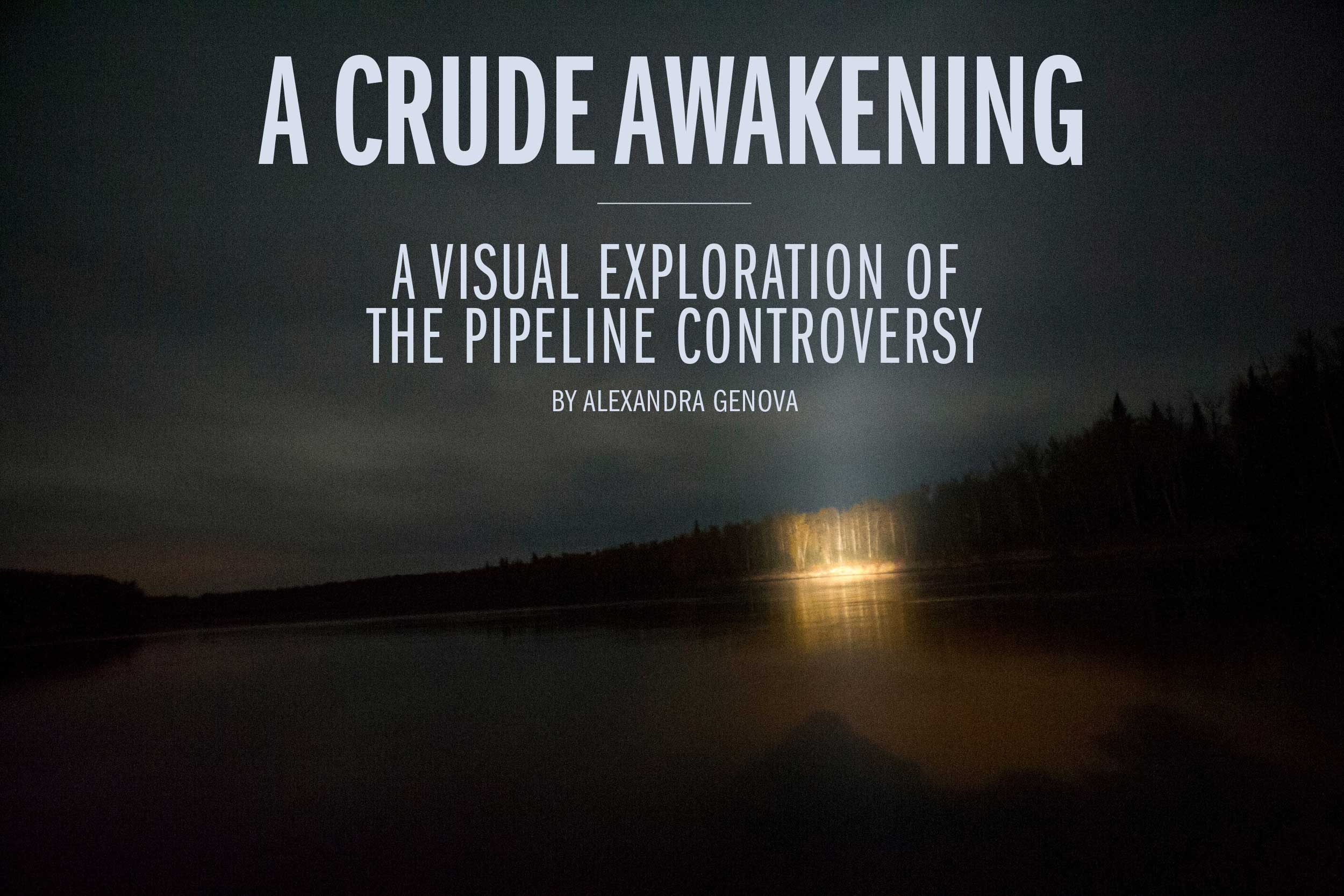

Health and Culture of Poor Communities Ian Willms

Ian Willms has spent years closely documenting the impact of oil production on First Nations of northern Alberta.

“The oil industry consumes the ecology. It poisons the water, it eats up the land, it displaces the natural migrations of caribou and moose and other animals that the nearby First Nation communities rely on. There are a lot of health problems, for instance an extremely rare form of bile duct cancer is being found at a very high rate. I’ve photographed a funeral for a miscarried infant and a young boy named Dez, aged seven, who has had numerous open-heart surgeries. The local doctor believes it is all caused by industrial pollution. Once the fur trade dried up and the fish were deemed unfit to sell at market because of pollution, welfare benefits and the oil industry became the community’s main sources of income. This forces a lot of people into a pretty bitter compromise. It’s been an ongoing process of assimilation since the colonists first arrived and the oil industry has sped that up.

“While Fort McKay First Nation has mostly embraced the industry, it’s very important to the health of all those communities to be able to live in traditional ways, exercise their culture and re-connect with their identity; it’s paramount to mental health. Their connection and staggering knowledge of the ecology goes right down to a cellular level. Taking away their land takes away their agency to heal and the freedom to exercise their spirituality. Keystone XL will grow the industry, meaning more investment in expansion into Fort Chipewyan territory. If that happens it’ll be catastrophic for the hunting and fur trapping and fishing. It’ll be the end of an era for a lot of people.”

Air Pollution Alex Maclean

In 2014, Alex MacLean used aerial photography to document the supply and demand of both ends of oil production – from the Alberta Tar Sands down to the Texas Gulf refineries.

“When I got to the Alberta Tar Sands it was really horrifying to see its scale and size – and the extremes they go to to produce oil. The companies at Tar Sands will say nothing toxic leaves the site but that is absurd; you can see huge plumes of smoke and haze that carries air pollution going downwind, which all ends up dropping toxins into the forest 100 or 200 miles away. The destruction of the Boreal Forest, which is a huge carbon sink, has a massive impact on the acceleration of climate change.

Then you look at the refineries and what it means for the surrounding population living with that kind of air pollution and the health issues associated with it. It’s just appalling that you would expose people to those kinds of toxins. You look at those towns, how poor and degraded they are as a result of that. What is perhaps most hopelessly disturbing is the scale of what money can buy. When the oil companies spend several hundred million dollars trying to buy political influence, you realize the magnitude and power of the industry.”

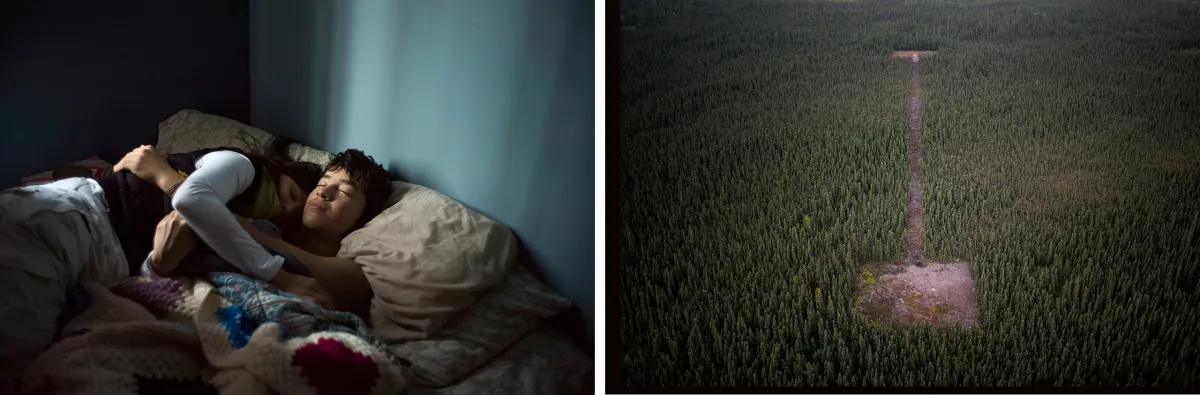

Deforestation Jiri Rezac

Jiri Rezac began photographing the Alberta Tar Sands 10 years ago, mapping the impact of development on the surrounding ecology.

“The Boreal Forest is the largest primary forest on the planet and the Alberta Tar Sands cut right through it. The tar deposits are removed by open cast mining which requires the wholesale removal of the peat land and the Boreal forest, which is a huge carbon sink, that can never be replaced. The lower deeper levels of tar are removed through a method called SAG-D. Before either of these takes place, the process begins with seismic surveys like in other forms of oil exploration, which hacks mile long lines and well pads into the forest. This has destroyed the habitat and the ecosystem of the forest. The geese are gone. The caribou are gone. This is very detrimental to the First Nations people who live along that land.

“There is an attempt at restoration but it’s the same as growing grass over landfill. Syncrude has a show plot right next to a toxic tailings pond, which is essentially a small pen about a half an acre in size, surrounded by a fence. They’ve put a couple of bison on it to demonstrate that something’s living here again. But it’s no more natural than a cattle farm.”

Oil Spills and Leakages Alyssa Schukar

Alyssa Schukar has closely documented the environmental legacy of oil production on East Chicago communities and photographed on assignment at Standing Rock.

“Whiting Refinery in East Chicago [which processes oil from the Alberta Tar Sands] has a long history of environmental abuse and a very long history of oil spills, which are pretty common. The scary thing about a spill is that it’s not necessarily something you see right away; it’s more subtle, things like elevated lead levels in the soil, which also comes from the century of steel production in the region. A lot of people have health issues like asthma and lupus. Then there are the beautiful hills and beach, which are protected areas and habitats, and the slag from the steel mills just covers that area – it covers most of East Chicago. Slag is really dangerous because it’s filled with a ton of toxic elements that people shouldn’t be interacting with, yet you have kids walking right along where the discharge has happened and where the oil spills have occurred.

“Then I travelled to Standing Rock and I really understood just how damaging the spills could be. If a spill were to happen there, it would basically ruin or at least cause major issues for Lakota drinking water and the main drinking water supply for about a third of the country. A lot of the beauty of North Dakota is the stillness of the water and the clarity. Looking at the situation in Chicago and then in Standing Rock makes you realize that our dependency on oil is just not sustainable.”

EnvIronmental Pollution Peter Essick

Peter Essick’s series on Alberta Tar Sands studied the damage of oil extraction on the land, rivers and downstream communities.

“The Alberta tar sands is dirty oil; it’s more expensive, more difficult and more environmentally damaging to get to than crude oil. There are clear environmental issues at stake but the oil industry continues to expand anyway.

“There is no clear fix with the environmental damage done by tailings ponds on the Tar Sands, where all the waste product from the extraction goes. It pollutes the clean water of the Athabasca River and affects the fish – which are coming out with all these red spots. There are also reports of members of a small village downstream having a rare form of cancer. The tailings ponds are also a large migratory bird area; in 2010, 500 birds died after landing on the ponds during a storm.”

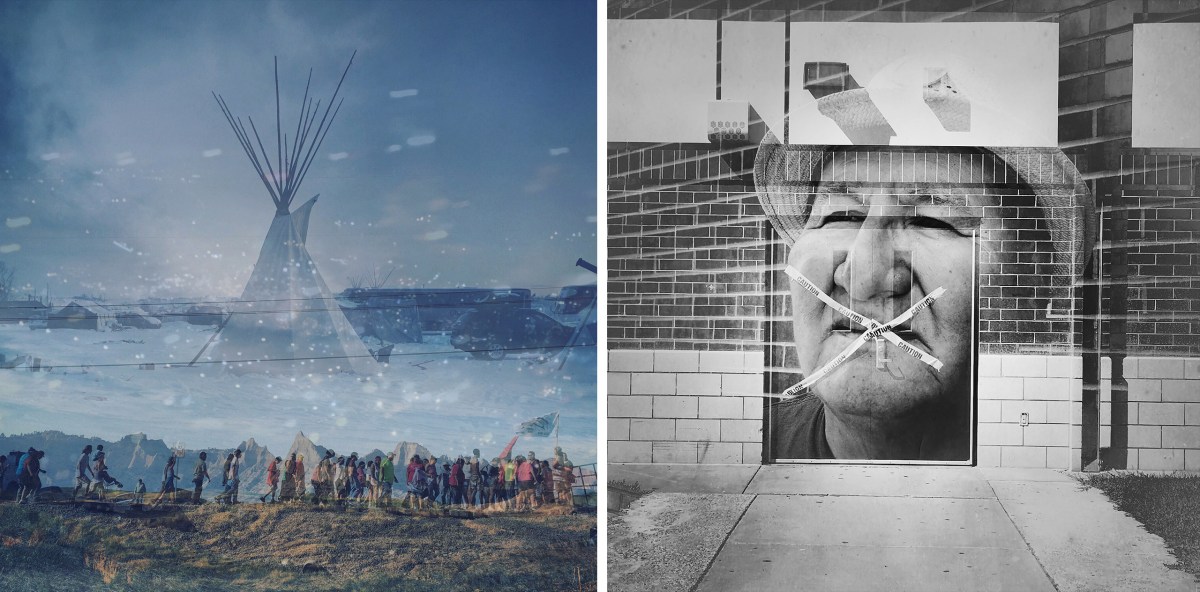

Desecration of Sacred Lands Daniella Zalcman

Daniella Zalcman‘s Pulitzer-Center funded project, Signs of Your Identity, reveals the damage of the residential school system on indigenous communities. Many of her subjects and their relatives travelled to Standing Rock to stand in solidarity with the Sioux Reservation.

“Standing Rock was about a return to sovereignty. The Treaty of Fort Laramie has been explicitly violated in so many different ways and this is an act of reclamation, of the Lakota saying: “We’re done with coercive assimilation. We’re done with land grabbing. And we also don’t want the water supply poisoned for the eighteen million people who live downstream.” They see themselves as stewards of the land for the next seven generations.

“A lot of the Lakota prophecies have to do with the land and the mythology of the Black Snake. The youth were a major part of bringing about this prophecy and reclaiming Native identity after what their ancestors had suffered. For example the reservations were essentially concentration camps located in the worst parts of the country and the coercive assimilation and physical and sexual abuse that occurred in the Indian boarding school system has left deep scars.

“There has been no real act on the part of the U.S. government to atone for cultural genocide. All this feeds into each other; the theft of property, identity, history and heritage of indigenous people that we still have not addressed in any systematic way. Scientific studies show that we pass trauma on in our DNA and that’s whether you’re a holocaust survivor or indigenous. Standing Rock is the first event in my lifetime where we have paid attention to an indigenous issue. We have damaged indigenous identity nearly irreversibly and we have to figure out collectively as a society how to reconcile this. That is absolutely the responsibility of every American.”

Treaty Rights Camille Seaman

Camille Seaman is an indigenous environmental photographer who spent several months at Standing Rock, documenting the developing story through Native eyes.

“I felt called — not just as an indigenous person of the Shinnecock Nation but also as a photographer — to join the people standing up for clean water and protecting the land at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Neither a history of injustice nor stereotypes tell the whole story; there is also resilience, strength, beauty and self-defining identity. The treatment of peaceful prayerful water protectors of Standing Rock show how little has changed as far as understanding and respect of Native peoples. Sovereignty, treaty rights religious freedom and protections all seem to mean nothing in the face of corporate profit.

“The wealthy predominantly white city of Bismarck somehow has hierarchy of privilege in regards to quality of life, opportunity and access to clean water. This country – if it truly wants to ever be “great” – must acknowledge the damages both past and continued, perpetrated against native peoples. It is the wisdom and philosophy of Native peoples that just may make it possible for humanity to survive the climate crisis and mass extinction we face as a species. Anyone really interested in surviving knows fossil fuel is dirty and unsafe. We rose up there and stood together. We will do it again and again.”

the Cattle Industry Jeff Jacobson

In September 2016, Jeff Jacobson travelled the route of the Keystone XL pipeline, capturing the land, livestock and people who will be affected by its development.

“The route of Keystone XL will go through fairly sparsely settled Great Plains areas for the most part – mostly ranch land. The immediate physical threat of these pipelines is if there’s a leak, [which] would be devastating for the drinking water but also for the ranchers and the whole cattle industry. The route of XL is also a major flyway for migrating birds; the Platte River in Nebraska in particular is a major staging ground. So if we continue to burn this, the wildlife is going to get affected one way or the other.

“But the great majority of people who live in the states where XL is going through support it. They are largely Republican states and they support the jobs that they have been told it will create. But have their opponents’ views been taken into consideration? The people with whom it will have a devastating impact? No. I’m not sure it’s in the nature of human beings to understand an existential threat until it affects their daily life. But the energy debate is one of the most overwhelming issues facing humanity.”

American Power Mitch Epstein

Mitch Epstein‘s American Power series examines how energy is produced and used in the American landscape and how it influences American lives.

“Oil is not drying up, coal is not drying up, so there’s a kind of indifference and laziness that’s endemic to [American] culture and to corporate culture. The deeper issues are what we take for granted in the cultural sense; we consume too much and our appetites are just too big. It’s about balance and right now, the scale has tipped all in one direction; there’s a kind of greed, recklessness and ruthlessness that’s just so rampant.

“Standing Rock brought to the fore the cultural and political issues we are still not facing as Americans. It’s sad and troubling; a kind of David and Goliath situation. As I saw with my American Power series, the government quickly comes to the aid of corporations who are big business. Ultimately, we appear to be at the mercy of a consumer culture that we’re conditioned by and a corporate governmental structure that we’re hemmed in by.”